“What Are You Going to Do Next?”

|

|

There aren’t very many qualitatively different types of computer interfaces in use in the world today. But with the release of Mathematica 9 I think we have the first truly practical example of a new kind—the computed predictive interface. If one’s dealing with a system that has a small fixed set of possible actions or inputs, one can typically build an interface out of elements like menus or forms. But if one has a more open-ended system, one typically has to define some kind of language. Usually this will be basically textual (as it is for the most part for Mathematica); sometimes it may be visual (as for Wolfram SystemModeler). The challenge is then to make the language broad and powerful, while keeping it as easy as possible for humans to write and understand. And as a committed computer language designer for the past 30+ years, I have devoted an immense amount of effort to this. But with Wolfram|Alpha I had a different idea. Don’t try to define the best possible artificial computer language, that humans then have to learn. Instead, use natural language, just like humans do among themselves, and then have the computer do its best to understand this. At first, it was not at all clear that such an approach was going to work. But one of the big things we’ve learned from Wolfram|Alpha is with enough effort (and enough built-in knowledge), it can. And indeed two years ago in Mathematica 8 we used what we’d done with Wolfram|Alpha to add to Mathematica the capability of taking free-form natural language input, and automatically generating from it precise Mathematica language code. But let’s say one’s just got some output from Mathematica. What should one do next? One may know the appropriate Mathematica language input to give. Or at least one may be able to express what one wants to do in free-form natural language. But in both cases there’s a kind of creative act required: starting from nothing one has figure out what to say. So can we make this easier? The answer, I think, is yes. And that’s what we’ve now done with the Predictive Interface in Mathematica 9. The concept of the Predictive Interface is to take what you’ve done so far, and from it predict a few possibilities for what you’re likely to want to do next. |

Mathematica 9 Is Released Today!November 28, 2012

|

|

I’m excited to be able to announce that today we’re releasing Mathematica 9—and it’s big! A whole array of new ideas and new application areas… and major advances along a great many algorithmic frontiers. Next year Mathematica will be 25 years old (and all sorts of festivities are planned!). And in that quarter century we’ve just been building and building. The core principles that we began with have been validated over and over again. And with them we’ve created a larger and larger stack of technology, that allows us to do more and more, and reach further and further. From the beginning, our goal has been an ambitious one: to cover and automate every area of computational and algorithmic work. Having built the foundations of the Mathematica language, we started a quarter century ago attacking core areas of mathematics. And over the years since then, we have been expanding outward at an ever-increasing pace, conquering one area after another. As with Wolfram|Alpha, we’ll never be finished. But as the years go by, the scope of what we’ve done becomes more and more immense. And with Mathematica 9 today we are taking yet another huge step. So what’s new in Mathematica 9? Lots and lots of important things. An amazing range—something for almost everyone. And actually just the very size of it already represents an important challenge. Because as Mathematica grows bigger and bigger, it becomes more and more difficult for one to grasp everything that’s in it. More » |

Latest Perspectives on the Computation AgeOctober 11, 2012

|

|

This is an edited version of a short talk I gave last weekend at The Nantucket Project—a fascinatingly eclectic event held on an island that I happen to have been visiting every summer for the past dozen years. Lots of things have happened in the world in the past 100 years. But I think in the long view of history one thing will end up standing out among all others: this has been the century when the idea of computation emerged. We’ve seen all sorts of things “get computerized” over the last few decades—and by now a large fraction of people in the world have at least some form of computational device. But I think we’re still only at the very beginning of absorbing the implications of the idea of computation. And what I want to do here today is to talk about some things that are happening, and that I think are going to happen, as a result of the idea of computation.

I’ve been working on this stuff since I was teenager—which is now about a third of a century. And I think I’ve been steadily understanding more and more. Our computational knowledge engine, Wolfram|Alpha, which was launched on the web about three years ago now, is one of the latest fruits of this understanding. More » |

Kids, Arduinos and QuadricoptersOctober 4, 2012

|

|

I have four children, all with very different interests. My second-youngest, Christopher, age 13, has always liked technology. And last weekend he and I went to see the wild, wacky and creative technology (and other things) on display at the Maker Faire in New York. I had told the organizers I could give a talk. But a week or so before the event, Christopher told me he thought what I planned to talk about wasn’t as interesting as it could be. And that actually he could give some demos that would be a lot more interesting and relevant. Christopher has been an avid Mathematica user for years now. And he likes hooking Mathematica up to interesting devices—with two recent favorites being Arduino boards and quadricopter drones. And so it was that last Sunday I walked onto a stage with him in front of a standing-room-only crowd of a little over 300 people, carrying a quadricopter. (I wasn’t trusted with the Arduino board.) Christopher had told me that I shouldn’t talk too long—and that then I should hand over to him. He’d been working on his demo the night before, and earlier that morning. I suggested he should practice what he was going to say, but he’d have none of that. Instead, up to the last minute, he spent his time cleaning up code for the demo. I must have given thousands of talks in my life, but the whole situation made me quite nervous. Would the Arduino board work? Would the quadricopter fly? What would Christopher do if it didn’t? I don’t think my talk was particularly good. But then Christopher bounced onto the stage, and soon was typing raw Mathematica code in front of everyone—with me now safely off on the side (where I snapped this picture): |

Wolfram|Alpha Personal Analytics for FacebookAugust 30, 2012

|

|

After I wrote about doing personal analytics with data I’ve collected about myself, many people asked how they could do similar things themselves. Now of course most people haven’t been doing the kind of data collecting that I’ve been doing for the past couple of decades. But these days a lot of people do have a rich source of data about themselves: their Facebook histories. And today I’m excited to announce that we’ve developed a first round of capabilities in Wolfram|Alpha to let anyone do personal analytics with Facebook data. Wolfram|Alpha knows about all kinds of knowledge domains; now it can know about you, and apply its powers of analysis to give you all sorts of personal analytics. And this is just the beginning; over the months to come, particularly as we see about how people use this, we’ll be adding more and more capabilities. It’s pretty straightforward to get your personal analytics report: all you have to do is type “facebook report” into the standard Wolfram|Alpha website. If you’re doing this for the first time, you’ll be prompted to authenticate the Wolfram Connection app in Facebook, and then sign in to Wolfram|Alpha (yes, it’s free). And as soon as you’ve done that, Wolfram|Alpha will immediately get to work generating a personal analytics report from the data it can get about you through Facebook. Here’s the beginning of the report I get today when I do this:

Yes, it was my birthday yesterday. And yes, as my children are fond of pointing out, I’m getting quite ancient… More » |

A Moment for Particle Physics: The End of a 40-Year Story?July 5, 2012

|

|

The announcement early yesterday morning of experimental evidence for what’s presumably the Higgs particle brings a certain closure to a story I’ve watched (and sometimes been a part of) for nearly 40 years. In some ways I felt like a teenager again. Hearing about a new particle being discovered. And asking the same questions I would have asked at age 15. “What’s its mass?” “What decay channel?” “What total width?” “How many sigma?” “How many events?” When I was a teenager in the 1970s, particle physics was my great interest. It felt like I had a personal connection to all those kinds of particles that were listed in the little book of particle properties I used to carry around with me. The pions and kaons and lambda particles and f mesons and so on. At some level, though, the whole picture was a mess. A hundred kinds of particles, with all sorts of detailed properties and relations. But there were theories. The quark model. Regge theory. Gauge theories. S-matrix theory. It wasn’t clear what theory was correct. Some theories seemed shallow and utilitarian; others seemed deep and philosophical. Some were clean but boring. Some seemed contrived. Some were mathematically sophisticated and elegant; others were not. By the mid-1970s, though, those in the know had pretty much settled on what became the Standard Model. In a sense it was the most vanilla of the choices. It seemed a little contrived, but not very. It involved some somewhat sophisticated mathematics, but not the most elegant or deep mathematics. But it did have at least one notable feature: of all the candidate theories, it was the one that most extensively allowed explicit calculations to be made. They weren’t easy calculations—and in fact it was doing those calculations that got me started having computers to do calculations, and set me on the path that eventually led to Mathematica. But at the time I think the very difficulty of the calculations seemed to me and everyone else to make the theory more satisfying to work with, and more likely to be meaningful. More » |

Happy 100th Birthday, Alan TuringJune 23, 2012

|

|

(This is an updated version of a post I wrote for Alan Turing’s 98th birthday.) Today (June 23, 2012) would have been Alan Turing‘s 100th birthday—if he had not died in 1954, at the age of 41. I never met Alan Turing; he died five years before I was born. But somehow I feel I know him well—not least because many of my own intellectual interests have had an almost eerie parallel with his. And by a strange coincidence, Mathematica‘s “birthday” (June 23, 1988) is aligned with Turing’s—so that today is also the celebration of Mathematica‘s 24th birthday. I think I first heard about Alan Turing when I was about eleven years old, right around the time I saw my first computer. Through a friend of my parents, I had gotten to know a rather eccentric old classics professor, who, knowing my interest in science, mentioned to me this “bright young chap named Turing” whom he had known during the Second World War. One of the classics professor’s eccentricities was that whenever the word “ultra” came up in a Latin text, he would repeat it over and over again, and make comments about remembering it. At the time, I didn’t think much of it—though I did remember it. Only years later did I realize that “Ultra” was the codename for the British cryptanalysis effort at Bletchley Park during the war. In a very British way, the classics professor wanted to tell me something about it, without breaking any secrets. And presumably it was at Bletchley Park that he had met Alan Turing. A few years later, I heard scattered mentions of Alan Turing in various British academic circles. I heard that he had done mysterious but important work in breaking German codes during the war. And I heard it claimed that after the war, he had been killed by British Intelligence. At the time, at least some of the British wartime cryptography effort was still secret, including Turing’s role in it. I wondered why. So I asked around, and started hearing that perhaps Turing had invented codes that were still being used. (In reality, the continued secrecy seems to have been intended to prevent it being known that certain codes had been broken—so other countries would continue to use them.) I’m not sure where I next encountered Alan Turing. Probably it was when I decided to learn all I could about computer science—and saw all sorts of mentions of “Turing machines”. But I have a distinct memory from around 1979 of going to the library, and finding a little book about Alan Turing written by his mother, Sara Turing. And gradually I built up quite a picture of Alan Turing and his work. And over the 30+ years that have followed, I have kept on running into Alan Turing, often in unexpected places. |

Announcing Wolfram SystemModelerMay 23, 2012

|

|

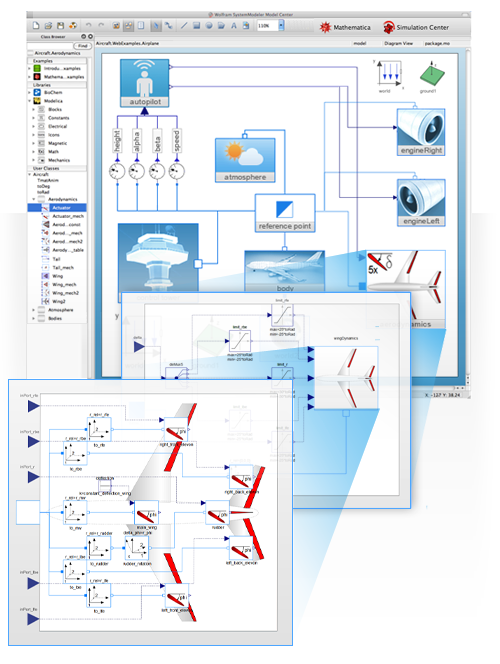

Today I’m excited to be able to announce that our company is moving into yet another new area: large-scale system modeling. Last year, I wrote about our plans to initiate a new generation of large-scale system modeling. Now we are taking a major step in that direction with the release of Wolfram SystemModeler. SystemModeler is a very general environment that handles modeling of systems with mechanical, electrical, thermal, chemical, biological, and other components, as well as combinations of different types of components. It’s based—like Mathematica—on the very general idea of representing everything in symbolic form. In SystemModeler, a system is built from a hierarchy of connected components—often assembled interactively using SystemModeler‘s drag-and-drop interface. Internally, what SystemModeler does is to derive from its symbolic system description a large collection of differential-algebraic and other equations and event specifications—which it then solves using powerful built-in hybrid symbolic-numeric methods. The result of this is a fully computable representation of the system—that mirrors what an actual physical version of the system would do, but allows instant visualization, simulation, analysis, or whatever. Here’s an example of SystemModeler in action—with a 2,685-equation dynamic model of an airplane being used to analyze the control loop for continuous descent landings: |

Looking to the Future of A New Kind of ScienceMay 14, 2012

|

|

(This is the third in a series of posts about A New Kind of Science. Previous posts have covered the original reaction to the book and what’s happened since it was published.) Today ten years have passed since A New Kind of Science (“the NKS book”) was published. But in many ways the development that started with the book is still only just beginning. And over the next several decades I think its effects will inexorably become ever more obvious and important. Indeed, even at an everyday level I expect that in time there will be all sorts of visible reminders of NKS all around us. Today we are continually exposed to technology and engineering that is directly descended from the development of the mathematical approach to science that began in earnest three centuries ago. Sometime hence I believe a large portion of our technology will instead come from NKS ideas. It will not be created incrementally from components whose behavior we can analyze with traditional mathematics and related methods. Rather it will in effect be “mined” by searching the abstract computational universe of possible simple programs. And even at a visual level this will have obvious consequences. For today’s technological systems tend to be full of simple geometrical shapes (like beams and boxes) and simple patterns of behavior that we can readily understand and analyze. But when our technology comes from NKS and from mining the computational universe there will not be such obvious simplicity. Instead, even though the underlying rules will often be quite simple, the overall behavior that we see will often be in a sense irreducibly complex. So as one small indication of what is to come—and as part of celebrating the first decade of A New Kind of Science—starting today, when Wolfram|Alpha is computing, it will no longer display a simple rotating geometric shape, but will instead run a simple program (currently, a 2D cellular automaton) from the computational universe found by searching for a system with the right kind of visually engaging behavior. |

Living a Paradigm Shift: Looking Back on Reactions to A New Kind of ScienceMay 11, 2012

|

|

(This is the second of a series of posts related to next week’s tenth anniversary of A New Kind of Science. The previous post covered developments since the book was published. ) “You’re destroying the heritage of mathematics back to ancient Greek times!” With great emotion, so said a distinguished mathematical physicist to me just after A New Kind of Science was published ten years ago. I explained that I didn’t write the book to destroy anything, and that actually I’d spent all those years working hard to add what I hoped was an important new chapter to human knowledge. And, by the way—as one might guess from the existence of Mathematica—I personally happen to be quite a fan of the tradition of mathematics. He went on, though, explaining that surely the main points of the book must be wrong. And if they weren’t wrong, they must have been done before. The conversation went back and forth. I had known this person for years, and the depth of his emotion surprised me. After all, I was the one who had just spent a decade on the book. Why was he the one who was so worked up about it? And then I realized: this is what a paradigm shift sounds like—up close and personal. More » |