December 5, 2007

Perry, IA

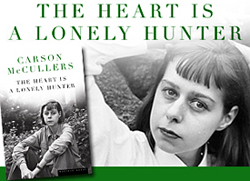

Last night I saw a waterfall of corn. It was almost midnight, and I was driving through cornfields in Iowa. Since it is autumn, the farmers were working late into the night, taking every advantage of the dry weather to harvest the corn. The tractor lights were blazing so brightly that I remembered a line from Carson McCullers’ The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter: “Nearly always the sky was a glassy, brilliant azure and the sun burned down riotously bright.” As the corn descended from the combine’s auger into the wagon and the lights shone through it, the kernels glimmered like gold coins in a pirate’s treasure chest.

|

|

|

Carlos Dews gives the keynote for Hometown Perry Iowa’s Big Read. Photo by Iris Coffin

|

|

This is not an everyday sight for me — a Los Angeles native living outside of Washington, DC, on her first trip to Iowa. The leaders of Hometown Perry Iowa, a museum that celebrates small town immigrant life, invited me to attend their Big Read kick-off, where scholar and professor Carlos Dews gave the keynote lecture about Carson McCullers’ life and art.

Carlos and I enjoyed long drives and several meals with the organizers of Iowa’s only Big Read for this grant cycle. There were even Reader’s Guides in the waiting room of the Mexican restaurant where we had lunch! With Bill Clark, Iris Coffin, Donna Emmert, Kathy Lenz, and Mayor Viivi Shirley, we spent many hours talking about the novel and speculating about possible reasons why a rural Iowa town was the only Big Read community to have chosen McCullers’ The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter.

Certainly the novel is dark. The characters are flawed, struggling, and often unlikable. The line between survival and despair remains perilously thin for these strong yet fragile creatures. But anyone who has experienced what Emily Dickinson described as the “formal feeling” that comes “after great pain” can appreciate the plight of McCullers’ six main characters.

I’ve never heard anyone identify The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter as a love story, but for me, this is its most poignant theme. Until talking with Carlos, I had never considered the novel’s theme of faith. Amid all the tragedy, McCullers might seem to mock hope. Love, faith, and hope: but the greatest of these is love, says the Apostle Paul in the New Testament. A close look may reveal that the novel reflects all three.

The novel begins, “In the town there were two mutes, and they were always together.” There seems no literary precedent for a protagonist like John Singer-a patient, thoughtful man and the town’s jeweler. His companion is a Greek named Antonapoulos, who is a rude, selfish glutton. Singer talks with his hands, but Antonapoulos rarely turns his head. Even “Singer never knew just how much his friend understood of all the things he told him.”

This is not a familiar love story. Similar to Flannery O’Connor, McCullers paints such peculiar characters, partly to demonstrate a clearer definition of love, one that is atypical and seemingly implausible. How rarely do we witness-not to mention give or receive-love freely bestowed without any intimation of sacrifice! When his companion is taken away from him, Singer is impoverished. At the end of a letter, Singer says of Antonapoulos, “the way I need you is a loneliness I cannot bear.” The presence of all the townspeople is no substitute for the man he calls his “only friend.” If we wonder what John Singer “gets” out of this relationship, we have missed the point.

During the Kick-off presentation, Carlos read a passage from McCullers’ other work The Ballad of the Sad Café to further illuminate her view of love:

The fact that [love] is a joint experience does not mean that it is a similar experience to the two people involved. …. [The lover] feels in his soul that his love is a solitary thing. He comes to know a new, strange loneliness and it is this knowledge which makes him suffer. …The beloved can also be of any description. The most outlandish people can be a stimulus for love. …The beloved may be treacherous, greasy-headed, and given to evil habits. …A most mediocre person can be the object of love which is wild, extravagant, and beautiful as the poison lilies of the swamp. …. Therefore, the value and quality of any love is determined solely by the lover himself.

We don’t often think of the solitariness of love; we like to think of it as union. But in McCullers’ world, the heart that loves is destined to further loneliness, to further hunting.

The hunt itself, this quest for something elusive, requires faith. In the same way that Antonapoulos seems unresponsive to John Singer, so Singer hardly responds to his neighbors. He doesn’t initiate friendship or conversations, although he seems to embrace both. The five other main characters visit Singer’s room frequently, often repeating their stories to him. They never know what he really thinks. Of this, Carlos Dews observed, “What makes faith faith is that you don’t necessarily get any messages back from prayer or worship. Faith comes from the belief that someone is listening to what you are saying. That’s what John Singer is for many of these characters. He’s deaf and mute, so they simply have to believe he’s listening.”

A question that repeated like a fugue in Perry concerned the ending: Is there any hope by the novel’s last page? Part of the answer lies in the novel’s final sentence- “He composed himself soberly to await the morning sun.” Despite John Singer’s physical inability to speak, Biff Brannon might be the novel’s most mute character. This lonely restaurant owner silently serves the town’s misfits. Everyone else who visits Singer talks incessantly, but not Biff. After the death of his wife, he doesn’t confide in anyone. He is eccentric, solitary, and oddly infatuated with Mick Kelley. Yet at the very end, the O’Connor-like “moment of grace” is given to Biff-an ordinary, isolated man left to plan the novel’s final funeral, who is bereft of anyone to love. Despite his loneliness, perhaps because of his quietly tragic life, McCullers ends her novel with Biff Brannon.

Perry, Iowa, is encouraging others to read a novel that, for me, is ultimately about those three greatest things: faith, hope, and love. It asks us to cherish love more fiercely when it is found, to possess faith in what cannot be seen, and to await the rays of the morning sun.