We all think we know what we're talking about when we discuss poverty. We have a clear mental image for the poverty of the developing nations. One of the targets for the millennium development goals, announced by the UN in 2000, was to halve the global proportion of absolutely poor people by 2015. At the time the target was announced, the definition of an absolutely poor person was anyone living on an income of less than $1 a day. That criterion has been nudged upwards, in response to new data about prices and purchasing power, to $1.25. There has and continues to be astonishing progress towards and beyond this target, which was achieved in 2010, five years ahead of its deadline – a fact that went eerily uncelebrated.

- Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

It is true that 1.2 billion people still live below the $1.25 threshold, but the proportion of humanity in that desperate condition is lower than it was. In 1980, more than half the world's population was living below this line; now, the number living below it is just over a fifth. This achievement is all the greater because it is relatively simple for small populations to improve their standard of living quickly; it is easier to move something small than it is to move something big. As the numbers grow, the achievement gets harder, which makes this transformation one that I don't think has any precedent in human history. We shouldn't get carried away: 1.2 billion absolutely poor people is still 1.2 billion too many, and the concentration of extreme poverty in sub-Saharan Africa, combined with a rapidly growing population, has meant that the number of people in poverty there has gone upwards, even as the proportion has gone down.

It's when we bring the idea of poverty closer to home that it gets more complicated. In fact, if I could, I would ban the word poverty from use in a UK context. That's not because there are not deprived and excluded people in this country, and it is also not because being relatively poor is not a serious predicament – there are, and it is, and the position of the relatively poor in the UK is growing worse. The problem, as I see it, is to do with the word poverty and its associations.

The first, and subtlest, of the difficulties is something that you could say was at least partly Jesus's fault. Three of the four Gospels tell the same story: a woman gives Jesus some expensive ointment, he uses it, and his disciples protest. They tell him that he could have sold the oil and given the money to the poor. Jesus disagrees, because, "The poor you will always have with you, but you will not always have me." This is often paraphrased or misremembered as "The poor are always with us," a sentence that returns more than half a billion Google hits. The original phrase "with you" isn't dismissive; there is something companionable, perhaps even necessary, about the permanent presence of the poor. This idea has penetrated deep into the collective consciousness: the idea that poverty is somehow inevitable, ineluctable, a given condition for a significant proportion of humanity.

Added to this is the fact that, in the Judeo-Christian tradition, poverty is close to being a virtue. Pretty much every saint is poor, and poverty is often a kind of holy USP, a defining characteristic. The chief Jesuit Pedro Arrupe said in 1968 that the Catholic church had "an option for the poor", and the fact that the Catholic church has a special interest in the poor is especially evident in the ministry of the current pope. Members of religious orders take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. We can half-consciously think that, if poverty isn't so bad spiritually, maybe it isn't so bad in other ways as well. The idea that poverty is inevitable, added to the idea that poverty has a link with virtue, complicates things. It is striking that the foundational document of the modern welfare state, the Beveridge report, doesn't use the word poverty, but sticks to "want", a term with much less value-baggage.

The difficulties don't end there. There is just as big a proportion of poor people in the UK as there is in the rest of the world: according to official statistics, one in five of us is poor. But when we talk about poverty in the UK, we aren't talking about the same kind of poverty as in the developing world. The definition of poverty generally used in the UK, as in the rest of the developed world, is set at 60% of median income. But these people aren't poor in the same way as those 1.2 billion living on less than $1.25 a day, obviously; they are poor in relation to the person who is in the middle of the income distribution, with half the country above them and half below. That median UK household income at the moment is £23,200, which means the official threshold for poverty in the UK is £13,920.

The first difficulty with this number is that many people simply don't believe it. They don't think that what is called poverty constitutes actual poverty. They don't think it is true to say that 13 million UK citizens are poor. Beveridge defined want as the lack of "what is necessary for subsistence", a much stricter criterion than the one that defines modern British poverty. Plenty of people agree with him. It is a secret thought, not much expressed in public, but summed up in Philip Larkin's poem Toads: "No one actually starves." This is one of those ideas that run strongly through modern Britain, without being as forcefully expressed as it is felt.

But it is there in polls showing the response to the coalition government's narrative about austerity. Have a look at the YouGov economy tracker: its polls show that a clear majority think austerity and cuts are "necessary" – at the moment, 58%, more than double the number who think they're unnecessary, at 27%. The number of people who think that cuts are good for the economy has been going up slowly but steadily for three years, from 34% in August 2011 (with 51% opposed) to 46% today (with 35% opposed). What these numbers imply, I think, is a lack of belief in narratives about poverty and hardship in the UK. The Great British Public doesn't really think times are as difficult as people say they are.

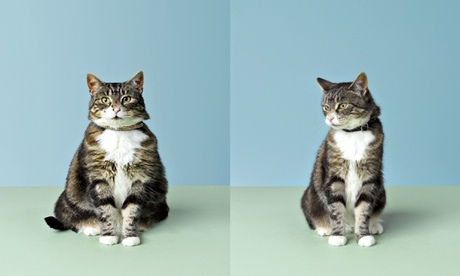

'"Poverty" has distracting moral associations; "inequality" doesn't.' Photograph: Sara Morris for the Guardian

'"Poverty" has distracting moral associations; "inequality" doesn't.' Photograph: Sara Morris for the Guardian

There is some evidence that this is because hearts in general have hardened. A recent report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation pointed out that the public expects levels of poverty to get worse, while at the same time "support for welfare spending... is at a historical low". Part of this resistance to helping the poor is because people don't believe in their poverty; and some of that is due to a confusion over, or disagreement with, that word "poverty". A person living on less than $1.25 is unarguably poor, in every sense. A person living on £13,000 a year is only arguably poor, because the threshold of 60% of median income is a definition of relative poverty. It is a measure only of how far the poor have fallen behind everyone else – a measure of inequality.

I don't for a second think that inequality is unimportant: rising levels of inequality are going to be the central focus of politics and economics pretty much everywhere in the world for the next decade. But I do think it's not quite the same thing as what is generally understood by the word poverty. Professionals discussing poverty know perfectly well that what they are talking about is relative poverty; they are fully aware of the nuances. But most of the rest of us aren't. People look around the UK and just don't believe in the existence of genuinely poor people.

This is why I would ban the word "poverty". ("Relative poverty" is too much of a mouthful.) Let's call it what it is – inequality. This would begin to iron out some of the oddities that emerge from the current framework. For instance, when lots of people lose their jobs and are suddenly in desperate financial straits, cutting their expenditure to the barest bones, lying awake at night sweating over bills and an uncertain future, even making their first tormented visits to the local food bank – this is all good news from the point of view of the poverty statistics. Rising unemployment means falling median income, which in turn means falling numbers of people below the poverty line – not because they're better off, but because the line has moved.

Real median income fell sharply during the Great Recession – by 8% in four years, an unprecedented amount – so the official poverty line fell, too. This fall has helped to conceal the way life has grown much harder for the people at the bottom. A family could have been in poverty in 2008, then risen out of poverty – even though it was struggling by on exactly the same income – just because the statistical goalposts had moved.

The current figure of 20% in relative poverty around the world may seem shockingly high, but it's the second lowest percentage since good data became available in the mid-90s. The pros regard these anomalies as a not too serious glitch, an irony of nomenclature. It seems to me more problematic than that. Calling the thing we're talking about by its real name would be a useful first step. To most of us, it makes no sense to say that having less money makes us less poor. But the idea that, because a majority of people have less money, we are now less unequal: that, I think, we can get our heads around.

An example of the way inequality risks being permanently baked into our societies is the current phenomenon of excessively low pay. It's an astonishing indictment of the current order that, of those 13 million at the bottom of the UK's income distribution, more than half are in work. What this means is that the tax and benefits system, which props up the incomes of the relatively poor, are also propping up the incomes of the shareholders in the companies that pay too little. Money that could and should go to employees in return for their labour instead goes to owners in return for their capital.

This is straight out of the pages of Thomas Piketty's Capital In The 21st Century: capital using its bargaining power to force down the price of labour – and then having the bill picked up by the state. I'm not sure there has been a precedent in British history for this arrangement, and it only really makes sense if you see it in a very sinister light: as preparation for a system of permanent inequality, in which most of us, in most jobs, are certain to be relatively poor. It's a basic premise of the social contract that work is the route out of deprivation. If that is no longer true, we need to take a hard look at the social contract, and start thinking about drawing up a new one.

"Poverty" has distracting moral associations; "inequality" doesn't. We may have taken on board the idea that the poor you will always have with you. That's very different from accepting the notion that rising inequality is a fact of life, a given that we'll all have to get used to. And by the way, although no politician I know of has had the guts to say that in public, that's what a lot of politicians and economists privately think. This is what they foresee: trends in globalisation, the hollowing out of both working- and middle-class employment, and the commodification of most skills (available at a fixed price from anywhere you want: a Polish builder, a data analyst in Bangalore) are going to create a permanent, and permanently widening, gap between the people at the top and everyone else. The people at the top will then do everything in their power to make sure that their children inherit their privileges – which they are very likely to do: the evidence shows that the more unequal a society, the more likely you are to inherit your life chances from your parents. If we think that the world is already too much divided into winners and losers, we ain't seen nothing yet.

The prospect is one of a society such as the one we live in, only more so. Nobody, in the Beveridge sense of the term, is lacking the means of subsistence: nobody is "poor". But it is a society that is also starting to look uncomfortably feudal, and many economists think it is overwhelmingly likely to be our future. I know, because they've told me. But this is a conversation we need to be having out in the open, because keeping quiet about it makes it more likely to happen.

This may sound grim, but I am not pessimistic. Rising inequality is not a law of nature – it's not even a law of economics. It is a consequence of political and economic arrangements, and those arrangements can be changed. Inequality in the developed world fell for most of the 20th century; we can make it fall for most of the 21st century, too. But it won't happen without sustained pressure on politicians from electorates. So let's get on with it. Let's start to make them hear what we're saying: it's about the inequality, stupid.