Patrick Holden is one of very few people you will meet in life who distinguishes between ‘inspiring’ and ‘uninspiring’ grass.

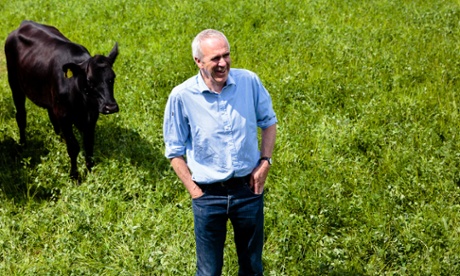

As we stand in a five acre field, one parcel of his 300 acre Bwlchwernen Fawr farm in West Wales, I become convinced that this is indeed ‘inspiring’ grass. The field that stretches out before us looks alive to the naked eye; the rye grass and white and red clover bright in the sunshine, moving, slightly, with the breeze.

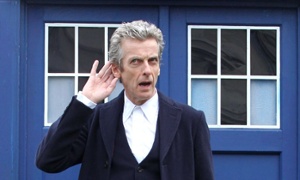

Until the ‘green revolution’ and the wholesale application of nitrogen fertilisers, the fertility to grow all arable crops was built by the kind of lush clover grass rotation I’m looking at. Holden, a bit of a superstar in the green movement (ex-head of the Soil Association and now head of Sustainable Food Trust), does a calculation in his head, quickly totting up the years: ‘So this has been in rotation six times,’ he says. Despite the day job, he has farmed this land continuously for 41 years. A day job, he says, is now key to maintaining small scale dairy farming, thanks to skewed economics.

Holden’s day job, for 15 years, was heading the UK’s premier organic food charity, the Soil Association, with Prince Charles among his green pals during critical years for British food. While he was in charge, the charity’s staff rose from five to over 180, and sales of organic produce in the UK grew from £50m to £2bn. But when he retired in 2011, handing over the reins to fellow farmer Helen Browning, he’d had his fill of that organic binary system where you’re either certified, or you’re not. He astounded conventional farmers when – on his way out at the Soil Association – he more or less apologised for an ‘us’ and ‘them’ system of food production. “Perhaps we have upset the conventional farming community by continually saying we were right and they were wrong,” Holden said at the Wales Organic Producers’ Conference in October 2010. “We should not be out there thinking and talking of ourselves as organic farmers, because that separates us from the rest of the farming community.”

He rightly gauged there was an appetite among the nation’s farmers for a less draconian yet sustainable approach, and promptly set up the Sustainable Food Trust. Investigative journalist and best-selling author Eric Schlosser, along with Holden’s West Welsh organic neighbour Peter Segger, are on the board of directors. The Trust gives Holden the latitude to talk soil and ‘true cost’ economics – such as the real price of nitrogen fertilisers – with farmers and food producers, and to be less fixated on the marketing of organic labels. He would like to introduce a sustainable index for farms to work their way through and thinks even ideological chasms should be talked through. This is something Holden excels at.

“Patrick loves talking about the minutiae of things, from carrot farming to the cheese making,” as TV chef Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall puts it. “He has an extraordinary energy; if you’re an environmentalist, there’s a lot to be gloomy about, yet he is never gloomy. There’s a glint in his eye and a boundless enthusiasm that picks me up.”

We look down on the farmhouse where he lives with his wife Becky and four of his eight – yes eight – children. Later we’ll have lunch there around a big kitchen table, the house heated by a groundsource heat pump. The scene is one from a children’s storybook: the farmer, the farmer’s wife, the farmhouse, the cows, the milking parlour. “Exactly!” says Holden. “Think of that image. The small mixed family farm that people show children before they go to sleep in order to connect them with the land, and the world, and give them a sense of security to fall asleep to. But in our generation that image has become complete fantasy!” He thinks that is a tragedy, and one that leaves us and our shopping baskets in an unprecedented, vulnerable state.

Still the storybooks persist with the image and so does Holden. I wonder if he’s trying to atone for doing his own bit to fuel population growth? He laughs. His drive comes from a desire for food security and resilience in the supply chain, not from breeder’s guilt. Everything Holden talks about with the Sustainable Food Trust is trialled on the farm. And so – in the antithesis to the vogue for industrialised systems that permanently house cows – the Holden herd of 85 Ayrshires is fed on homegrown peas and oats grown in the final, exploitative phase of the rotation. I have to say they are lovely cows, even Mrs Goggins who does her damndest to avoid going in for afternoon milking, resulting in a rollocking from the herdsman. Her calf is waiting and, understandably, her instincts are telling her he’d like her milk. It’s a reminder that even ‘nice’ farming is exploitative in some senses.

But that’s the interesting thing about Holden: you have the pragmatic farmer mixed with the biodynamic believer. “We’re hopefully nearing the end of chemical farming,” he says, sounding a little Pollyanna-ish. “... which of course Steiner was on about in 1924.”

This reference was inevitable. At some point in conversation with Holden, the philosopher Rudolph Steiner will always make an appearance. It tends to drive those who think that ‘magical thinking’ and anthroposophy have no place in sustainable agriculture completely nuts, and I have heard Holden referred to sniffily as a ‘biodynamic intellectual’. He tells me about the need for restoring soil vitality by going further than organic with homeopathic preparations, planting and harvesting, and taking into account the movement of the sun and the moon against the background of the planets in order to capitalise on favourable circumstances.

“Now we’re getting into the esoteric, right?” he says. “Some might say ‘twaddle’,” I volunteer helpfully. Undeterred, he references the experiments of the late Agnes Fyfe – who claimed to demonstrate the effect of the movement of the planets on plant sap – and a recent lecture he attended along the same lines. “Was it given by a biologist?” “No,” he replies, “and she wouldn’t have got her research published in Nature, and that’s the problem isn’t it? We’re obsessed with this scientific validation, but all science is built on hypotheses that comes out of observation and very often it takes years before a scientific hypothesis is proven to the point where it becomes an orthodoxy.”

Still, it is notable that despite being head of the UK’s biodynamic association his farm is not biodynamic, and when he sells sustainable agriculture to farmers, he tends to talk pragmatically about the true cost of nitrogen fertilisers rather than homeopathic soil preparations.

His own cows are “shepherded” along “inspiring” grass, grazing intensively and briefly so that the grass avoids going into defense mode, jettisoning its root system as happens in most pasture systems. They’ve even put in a special pathway to move the cows along more swiftly.

“Yes,” says Holden proudly, “We’ve redesigned our pastures to shepherd our cows. It’s the New Zealand system which we’ve been doing for a while, but you know what? I’ve only just really found out the fascinating principles behind it last week, from an amazing woman – Elaine Ingham – probably the world’s leading expert on soil microbiology.”

Anybody who thinks farmers are stuck in their ways and resistant to change needs to meet Holden. He is constantly collecting people, and scooping them up into a cloud of enthusiasm for sustainable farming. He’s recently been hanging out with renowned investor Warren Buffet’s son, Howard, on a combine harvester in Iowa. (“A great guy. He really gets soil!”) This won’t do much to calm the greens who accuse him of a brand of eco-capitalism.

But Holden, the son of a child psychiatrist and academic, and from a line of Oxford scholars, has always ploughed his own counter cultural furrow, starting by shunning Balliol College for Emerson Agricultural College in Forest Row, West Sussex, which taught farming along biodynamic principals. When he arrived there in 1973 it was with a bunch of fellow communards, including his former wife Lou. Everyone around called them “the hippies on the hill”.

Time has gone by, and still Holden has little time for orthodoxy. This is true even when that orthodoxy comes from the ‘green’ side. Take livestock as an example. For the last decade, in the face of climate change, the sustainability movement has had a considerable beef with ruminants and the ‘long shadow’ they cast, ecologically speaking. “Look, in West Wales it rains a lot,” he says. “We grow good grass. About 90% of the land in the county is temporary grass. What are you going to do? There’s a strong anti-livestock bandwagon rolling at the moment and it’s particularly anti-ruminants. But they’re the only animals that can digest the cellulose in clover and grass. So ruminants need to play a central part of that. I have really become a campaigner for the role of ruminants in sustainable foodsystems.”

I suggest to communicate that, he’ll need a snapper acronym than ‘the role of ruminants in sustainable foodsystems’. He is undeterred.

“Sustainability campaigners are already shifting their ground. NGOs, especially the conservation and the animal welfare groups, had a relatively shallow understanding about what constitutes sustainable agriculture. They (he includes the WWF and the RSPB in this grouping) accepted as inevitable that farming would become intensive and the only way to protect nature was to create reserves through the stewardship schemes on the margins of the otherwise intensively farmed land.”

But the RSPB’s State of Nature report published last spring showed that the reserves and the schemes weren’t the huge success that everyone had hoped. Holden asserts that the only way to protect nature is to farm sustainably, and that the NGOs are wising up to this. “This is fantastic! They have millions of members and supporters and we need them. When it comes to farming and food we face profound public ignorance.”

When he has a food beef he has never been shy about saying so. From 1979 to 2006 he grew carrots (as part of this very rotation) but he rather famously gave an interview to our own Felicity Lawrence, exposing how supermarket logistics had resulted in a farcical system of trucking eco carrots, his own and those from Highgrove (‘royal roots’), 230 miles to be washed and prepared before being returned to the locale to be sold, racking up the carbon footprint. The last straw came when he was delisted by the supermarket over quality control issues. The hippie on the hill commune disintegrated – as many West Wales hippie communes did when urbane metropolitan types tired of milking cows and hand-carving Welsh dressers.

But Holden wasn’t done. “I think from the outset, I was the one who loved it. I was the one who always wanted to do the milking, for example,” he recalls. Now of course he misses many milkings – the responsibility is devolved to a herdsman – while Holden is often busy travelling the world proselytising on the urgent need for holistic sustainable agricultural systems. Counter-intuitive perhaps, as so often Holden claims that this has made him closer to the soils of Bwlchwernen Fawr than ever.

Off the shelf: are people finally turning away from supermarkets?

Micro-dairies: small farmers fight back

Interested in finding out more about how you can live better? Take a look at this month’s Live Better challenge here.

The Live Better Challenge is funded by Unilever; its focus is sustainable living. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.