What Your Klout Score Really Means

- |

- 7:32 pm |

- Permalink

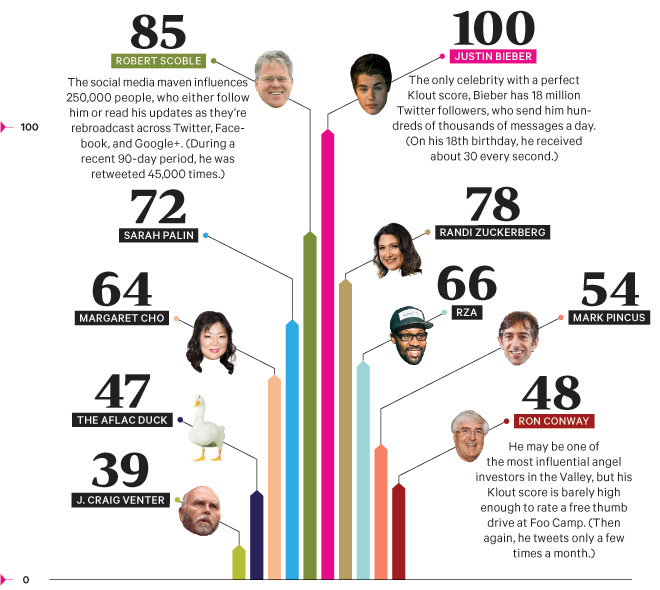

All-Star Klout-Off!

Klout scores are compiled using proprietary algorithms that purport to quantify online influence. Size matters: Large followings on Twitter or Facebook can boost your rating. But it’s more important to have a high percentage of posts that are liked or retweeted. And just interacting with someone who has lots of Klout can jack up your score.—S.S.

Photos: Scoble: AP; Zuckerberg, Conway, Rza: Getty; Corbis

For a guy whose company seems to encourage loudmouthed self-promoters, Fernandez himself is remarkably soft-spoken and self-effacing. When I meet him in Klout’s offices, beneath a freeway overpass in San Francisco’s South of Market district, he flops down in an armchair, wearing a faded plaid shirt and a pair of raggedy sneakers. His hair is unkempt, his smile goofy, his manner friendly and open. He frequently asserts that Klout has succeeded only because he “hired people much smarter than me.”

Fernandez’s humility is key to his appeal. “If the CEO of Klout was a type-A guy, I think many of us would take offense when he talks about scoring us or judging us,” says David Pakman, a partner at Venrock. “But Joe’s not like that. He’s uniquely suited to this role.”

Fernandez got the idea for Klout in 2007, when at the age of 30 he had surgery to correct a jaw misalignment that had plagued him for years. Doctors wired his jaw shut for three months. “It was mentally and emotionally way tougher than I thought it would be,” Fernandez says. “I couldn’t talk to anyone. Even my mother couldn’t understand what I was saying.” He resorted to posting on the still-young Facebook and Twitter as his only means of communication. He posted his opinions on videogames, suggested neighborhoods to check out, and recommended restaurants—even though he wasn’t eating solid food. Every time a family member or friend responded to one of his updates, he relished his ability to sway their behavior. And as he looked over his feed he saw countless other people doing the same thing, recommending products or activities to an enthusiastic audience. Fernandez began to envision social media as an unprecedented eruption of opinions and micro-influence, a place where word-of-mouth recommendations—the most valuable kind—could spread farther and faster than ever before.

Fernandez’s vision was helped along by a series of biographical confluences. He had studied computer science at the University of Miami, going on to help run a pair of analytics companies—one in education, the other in real estate—that worked with massive, unwieldy streams of information. So he was familiar with the concept of finding patterns and value in large amounts of data. And as the child of a casino executive who specialized in herding rich South American gamblers into comped Caesars Palace suites, Fernandez saw up close and from a young age the power of free perks as a marketing tool.

With his jaw still clamped shut, recovering in his Lower East Side apartment, Fernandez opened an Excel file and began to enter data on everyone he was connected to on Facebook and Twitter: how many followers they had, how often they posted, how often others responded to or retweeted those posts. Some contacts (for instance, his young cousins) had hordes of Facebook friends but seemed to wield little overall influence. Others posted rarely, but their missives were consistently rebroadcast far and wide. He was building an algorithm that measured who sparked the most subsequent online actions. He sorted and re-sorted, weighing various metrics, looking at how they might shape results. Once he’d figured out a few basic principles, Fernandez hired a team of Singaporean coders to flesh out his ideas. Then, realizing the 13-hour time difference would impede their progress, he offshored himself. For four months, he lived in Singapore, sleeping on couches or in his programmers’ offices. On Christmas Eve of 2008, back in New York a year after his surgery, Fernandez launched Klout with a single tweet. By September 2009, he’d relocated to San Francisco to be closer to the social networking companies whose data Klout’s livelihood depends on. (His first offices were in the same building as Twitter headquarters.)

Fernandez says that he sees Klout as a form of empowerment for the little guy. Large companies have always attempted to woo influential people. It’s why starlets get showered with free clothes and athletes get paid to endorse sports drinks. It’s also why, once blogging took off, popular scribes like mommy blogger Dooce started receiving free washing machines. But Fernandez says that, until the dawn of social media, there was no way to pinpoint society’s hidden influencers. These include friends and family members whose recommendations directly impact our buying decisions, as well as quasi-public figures best known for their Twitter updates—like, say, San Francisco sommelier Rick Bakas, whose 71,000-plus followers hang on his every wine-pairing suggestion. “This is the democratization of influence,” says Mark Schaefer, an adjunct marketing professor at Rutgers and author of the book Return on Influence. “Suddenly regular people can carve out a niche by creating content that moves quickly through an engaged network. For brands, that’s buzz. And for the first time in history, we can measure it.”