As an emerging discipline still defining itself, Digital Humanities offers an ideal opportunity to reflect on its broader disciplinary narratives. Julianne Nyhan and Oliver Duke-Williams examined its collaborative nature through the lens of publication patterns in some of its core journals. They found predominately single-authored papers were published during the time-frames, suggesting individual scholarship is still playing a large role. But this may be a case where publication and assessment haven’t yet caught up with wider disciplinary practice.

As an emerging discipline still defining itself, Digital Humanities offers an ideal opportunity to reflect on its broader disciplinary narratives. Julianne Nyhan and Oliver Duke-Williams examined its collaborative nature through the lens of publication patterns in some of its core journals. They found predominately single-authored papers were published during the time-frames, suggesting individual scholarship is still playing a large role. But this may be a case where publication and assessment haven’t yet caught up with wider disciplinary practice.

Collaboration is widely considered to be both synonymous with and essential to Digital Humanities (DH). This is because one person can rarely possess all of the (inter)disciplinary and technical knowledge needed to implement many DH projects. Collaborations can take many forms, for example, between technical and non-technical researchers or research groups. They may also include input from more amorphous groups like the “general public” who participate in crowd sourcing projects. Indeed, one of the earliest documented examples of a Digital Humanities project, Fr Roberto Busa’s Index Thomisticus, was underpinned by a wide-ranging collaboration, not only with IBM, but also including, at one point, a team of 60 who worked directly on the project (PDF Busa 1980, p.86). He also founded a training school for female keypunch operators who worked on the project’s texts.

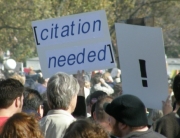

In DH research literature, in grey literature and on scholarly blogs the collaborative nature of DH is often evidenced by reference to the joint and multi-authored publications that are seen as characteristic of the field. However, literature from the domain of information science emphasises that collaboration and co-authorship do not necessarily have a parallel relationship (see, for example, Subramanyam (1983), Laudel (2002). Bošnjak, L. & Marušić, A., 2012). There are many reasons for this, for example, different disciplines (and even teams) have different conventions for deciding who should be named on a paper and in what order (only those who wrote the paper? Should those who programmed the computational model that the research is based on be listed as co-authors or named in the acknowledgements?) Looking to the DH context, we noted that there does not seem to be a consensus about authorship conventions. Indeed, if there were it is unlikely that statements such as the Collaborators’ Bill of Rights and the INKE project charter would have been made. We also noted that core journals such as Literary and Linguistic Computing (LLC) and Digital Humanities Quarterly do not, to the best of our knowledge, include authorship statements. Indeed, given the wide range of disciplines that publish under the umbrella term ‘DH’ it may well be that a suitable definition is impossible to reach.

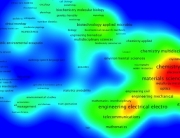

Image credit: Social Network Analysis Visualization by Calvinius (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Image credit: Social Network Analysis Visualization by Calvinius (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

With the above caveats in mind, we asked whether there is any mismatch between the collaborative character that is attributed to DH and the evidence of publication patterns and practices that can be detected in some of its core journals. As this research was undertaken within the context of a wider project on the history of Digital Humanities we also wondered about the historical dimension: how have levels of joint and multi-authorship in DH changed since the first journal of the field, Computers and the Humanities, was established in 1966?

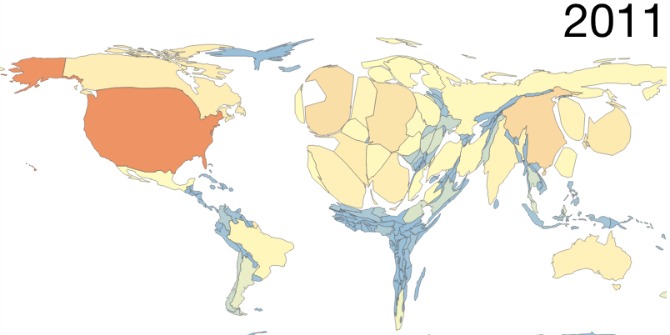

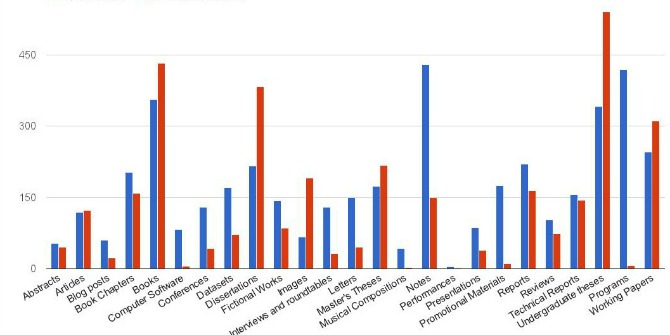

We proceeded by extracting and analysing the bibliographical metadata of Computers and the Humanities (CHum) (1966 – 2004); and LLC (1986-2011). Our control was the Annals of the Association of American Geographers (1966-2013), we chose this journal because it is a respected Geography journal that attracts a range of research, including research with technical applications or methodologies, for example GIS. Our findings were that two of the core journals we looked, CHum and LLC, published predominately single-authored papers during the indicated time-frames. In CHum we found a significant increase in dual and triple authored papers but not in four and five authored papers. In LLC we found a significant increase in triple authored papers but not in joint-authored, or four or five-authored papers.

Looking to establish a wider comparative context, we found that in AAAG single authored papers also predominate. Interestingly, multi-authored papers showed increases in all forms and thus are more wide-ranging than in either LLC or Chum. The author connectivity scores show that in CHum, LLC and AAAG there is a relatively small cohort of authors who co-publish with a wide set of other authors, and a longer tail of authors for whom co-publishing is less common.

Why does this matter, you might reasonably ask? One possible interpretation of these findings is that some single-authored DH publications (leaving aside, for a moment, ongoing debates about what DH actually is) are detached from the collaborative conditions of their gestation. Indeed, as Nowviskie has convincingly argued, practices that underscore decisions about hiring and promotion have, to some extent, made this a necessity:

The multivalent conditions in which we encounter and create digital scholarship make evident the impoverishment that comes with concentration, by tenure and promotion committees responsible for evaluating the scholarly output of colleagues working in new media, on products of scholarship divorced from their networks of cooperative production and reception (PDF)

However, numerous examples that underline the complexity of such issues, and the diversity of DH publication practices, can be pointed to, for example, the research of Willard McCarty who reflected in his recent Busa award lecture that “I am a quite old-fashioned scholar, who works by himself, shuns collaborative teams and the grants that fuel them …” (full text)

If these findings are interpreted as implying that individual scholarship has played a much greater role in DH than is often recognised we may ask why the narrative of collaboration has been so important to DH? There are obvious practical considerations: DH research often cannot be done without collaboration. Thus, when negotiating with senior administrators and university management about the setting up of Centres and teaching programmes one presumes that it was necessary for scholars to emphasise this dimension of the field in order to ensure access to requisite infrastructures. Yet, it is widely known that collaborative publication has been increasing across the disciplines since post WW2. With reference to this broader context and the fact that sole-authorship dominated in at least two core DH journals, one wonders about the wider symbolic importance of the motif of collaboration to the DH community. To what extent has collaboration perhaps served a social and organisational function? Should it also be interpreted in a more symbolic way as a useful banner under which DH researchers (who are often drawn from a wide range of home disciplines and use a range of methods) have rallied? Indeed, given that DH is arguably in the process of moving in from the margins and more towards the mainstream is it perhaps time to bring that banner into closer focus, in order to investigate its dimensions and significance more?

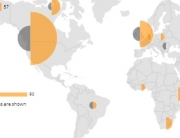

Is Digital Humanities as collaborative as it claims to be? We cannot answer this question from this research, not only because, as we have pointed out, joint authorship does not necessarily indicate the presence (or absence) of collaboration but also because a wider statistical analysis of publication patterns in the Digital Humanities and the Humanities as whole would be needed in order to answer this. At the moment we are in the process of extending our research, not only to include other journals but to also consider issues such as how gender, geography and seniority interconnect with these findings. What we can say is that our research points to the need for a deeper and more wide-ranging, qualitative and quantitative examination of the notion of collaboration in DH and current ways of signalling it. When this is combined with comparative and historical research we may be better able to understand such developments within the context of the Humanities as a whole and the history of Digital Humanities.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Dr Julianne Nyhan is lecturer in Digital Information Studies in the Department of Information Studies, University College London. Her research interests include most aspects of digital humanities (with special emphasis on meta-markup languages and digital lexicography); information history; the history of computing in the Humanities; and oral history. Her recent publications include Digital Humanities in Practice (Facet 2012), Digital Humanities: a Reader (Ashgate 2013) and Clerics, Kings and Vikings: essays on Medieval Ireland (Four Courts, at press). Among other things, she is a member of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Peer Review College, the communications Editor of Interdisciplinary Science Reviews and a member of various editorial and advisory boards. At present her research is focused mostly on the ‘Hidden Histories: Computing and the Humanities c.1949–1980’ project (http://hiddenhistories.omeka.net/). She tweets @juliannenyhan and blogs at http://archelogos.hypotheses.org/. Further information is available here: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/dis/people/juliannenyhan

Oliver Duke-Williams is a lecturer in Digital Information Studies in the Department of Information Studies at UCL, and was previously a Senior Research Fellow at the School of Geography, University of Leeds. His research interests include web-based access to geographic data (including presentation of spatial data, and dissemination of demographic data); disclosure control issues, especially those associated with migration and commuting data, and the past, present and future of census taking and other demographic information capture in the UK.

Hi — this is an interesting project. Thanks for sharing it. I direct the Office of Digital Humanities at the US National Endowment for the Humanities. I was thinking that another good resource for your study of collaboration might be our database of funded projects. For example, here’s a link to every DH project ever funded by ODH:

http://1.usa.gov/1qFVTrp

There are 362 projects as of this writing. Each one contains an abstract for the project which usually give you a sense of whether it is collaborative or not. Some also have two or more formal co-PIs.

Brett