Our view is that the protesters should not be expected to offer clear public-policy guidance. In this essay, we'll lay out why. The Occupy protesters have succeeded in creating emotionally impacting, ethically guided collective action. But they're constrained by the forms of expressing political dissent that Americans are familiar with. Most people are habituated to express their political dissent by way of a limited number of options: individualism, token gestures of solidarity, joining an existing campaign, and partaking in a standard form of political participation. None of those forms are on the scale of action needed to deal with the problems to which OWS has addressed itself.

In other words, Occupy protesters have to create not just a set of demands, but a set of new ways of demanding. That sort of social experiment requires breaking from the status quo to find new leverage points on existing power structures. That's what Occupy has attempted to do. This new type of emotionally impacting, ethically guided collective action is not incoherent, but it may be illegible.

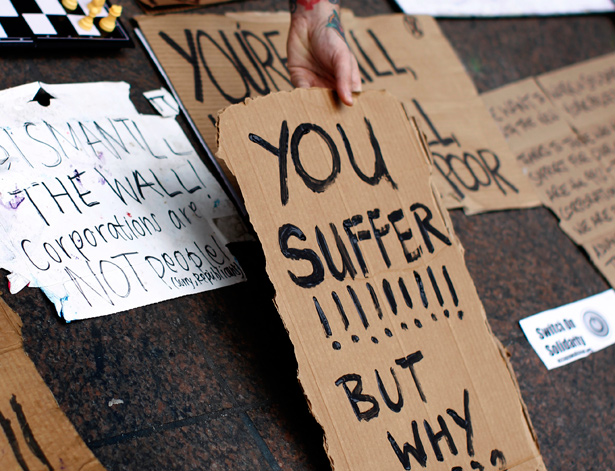

When we use these terms, we have very specifics meanings that are useful to keep in mind. Emotionally impacting experiences are ones in which participants want to express their views passionately with likeminded others and against shared opponents. It takes lots of energy to maintain this passion over time. Gathering together in a symbolically special place like Zuccotti Park and engaging in solidarity building activities, like chants and human microphone speech, are effective mechanisms for keeping up affect.

Ethically guided actions are motivated by intentions the majority of participants view as inherently ethical--as opposed to, say, aesthetic or social. The protesters see themselves as taking a moral stand. Social events may occur. Famous musicians and actors may stop by. But, the majority of protesters aren't camping out for this. (We're focusing only on the participant perspective. Others, notably Right Wing critics, might assess the guiding intentions quite differently.)

Collective actions refers to problem-solving that has several features: the protesters view the matter grabbing their attention as first and foremost concerning the public good; the protesters recognize the benefit of solving the public good problem extends far and wide, way beyond the narrow confines of special interest lobbying; and the protesters understand acceptable results cannot be achieved if individuals are left alone to pursue their own advantage within a broken system.

Many accounts have attempted to grapple with where the Occupy protests started and what they mean. We'd like to offer a deeper look at the five key ingredients underlying OWS.

The first ingredient might be the most important. It is the experience of a shared catastrophe. Naomi Klein, who has emerged as a leading voice of OWS, contends that the protests are a form of "shock resistance." As she sees it, this resistance mobilized to counter deleterious political processes--processes that took advantage of powerless and scared citizens wounded by financial crisis "shocks". Her guiding example is the $700 billion dollar TARP program. Why did the country go from opposing it to endorsing it without requiring structural adjustments? Klein's answer: panic.

OWS didn't take shape because upset citizens merely read or heard about the subprime mortgage scandal. They personally lost their homes or jobs.Klein's thesis is hard to assess, not least because it reposes upon ideas developed at length in her book The Shock Doctrine. That said, her general emphasis upon catastrophe as cause is apt. OWS didn't take shape because upset citizens merely read or heard about the subprime mortgage scandal. They personally lost their homes or jobs. Or, they are directly connected to others who experienced these misfortunes. In both cases, intense feelings have been incited about a social contract ending, one that rewarded hard work and protected participants in the ownership society.

In a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, co-authors Francisco C. Santos and Jorge M. Pacheco argue that the propensity toward collective action increases as the perceived risk of catastrophic loss also increases. Applying that view here, we can say that the shared experience of the economic crisis has likely increased the willingness of many Americans to work collectively to cope with their emotionally resonant trauma, regardless of political ideology. This link between risk and collective action explains why the Tea Party movement and OWS have structural similarities, despite embodying powerful ideological differences. At bottom, both groups were forged by experiences of perceived catastrophes, present and future alike.

The second ingredient is injustice. To give rise to a protest like OWS, a catastrophe must have moral underpinnings and be perceived as perpetrating unfairness. Had the collective failure of bubble speculators, regulators, and politicians resulted in the perception of shared sacrifice, the social response to what now is referred to as the Great Recession may have been more muted. Instead, the perception fueling OWS is that the burden of the economic collapse is being borne disproportionately. It is no surprise, then, that emotions are heated to incendiary.Political despair is the third ingredient for the type of ethically guided collective action at stake in OWS. People motivated to join OWS believe we now face the failure of a corrupt, hierarchical, and centralized leadership structure that cannot effectively respond to the crisis. Collective action thus emerges as a solution to problems in which enforcement by officially sanctioned outside parties, such as regulators, fails. Both the Tea Party and the OWS movements share the perception that established governance institutions are morally (and perhaps irredeemably) corrupt, and that alternative governance structures based upon a loose affiliation of like-minded individuals working together voluntarily, rather than in response to coercion, are preferable.

The fourth ingredient is a capacity to form an emergent community, one where membership is defined as a reaction to the underlying catastrophe. The OWS protesters have created solidarity around the group identity of being in the "99 percent," and this designation features prominently in calls to action. Without such a clear identifier, it might have been difficult for the protesters to convince themselves and others that they are part of something grand, namely, a movement. A comparable claim can be made on behalf of those who see themselves as members the Tea Party--a title that not too long ago would have seemed to be a mere historical designation.

The fifth ingredient is effective participant communication. Many extol the virtues of social media and depict it as a catalyst for the flat organizational structure of the first major political movements of the 21st century. For example, Jonathan Askin, a Brooklyn Law School professor, goes so far as to say: "We are witnessing the birth of a new, sustainable, non-hierarchical, pivotable movement, run by a new generation, with digital tools, capabilities, processes and flexibilities that the analog world--and its old, corporate and political, guard--cannot yet process."

Skeptics, by contrast, respond that political movements have come and gone long before the invention of Twitter. Malcolm Gladwell's remarks from last year on "Why the revolution will not be tweeted" are especially germane.

Stipulating that there are legitimate points of disagreement on these matters, there can be no doubt that organizational structure of the OWS and the Tea Party are qualitatively different than previous movements. Both organizations, for instance, eschew centralized leadership structures that ordinarily are necessary to coordinate large-scale activities. The compelling argument, therefore, is that the ultra-low cost and ubiquitous nature of information communication technologies has enabled a new organizational structure for what otherwise might be an old-fashioned politico-cultural movement.

So, those are the factors structuring the movement. Occupy observers, meanwhile, have expected it to produce something they could immediately understand. Unfortunately, the structure of political dissent in America is mismatched in scale to the intense emotions, ethical demands, political despair, emerging identity, and complex systems driving OWS. It's this mismatch that's caused so much confusion about what Occupy, as a movement of people, wants or could be.Let's go through the extant familiar forms of political dissent more rigorously. As we noted before, most people are habituated to express their political dissent in a limited number of ways: individualism, token gestures of solidarity, joining an existing campaign, and partaking in a standard form of political participation. A relevant individual choice is to move personal savings from a large to small bank. This gesture can be a protest statement against the "too big to fail" ideology, and it can occur in total isolation from one's social circle. A great sense of pride can be felt going against the grain and defying complacent others.

A token gesture of solidarity is an action that signifies an alignment of moral values, but cannot be reasonably expected to make a significant impact. An example is clicking the "like" button on Facebook to signify one is a fan of the "Move Your Money" project, a campaign that helps people locate banks not associated with the Wall Street taint. Crossing the threshold from tokenism to actually joining the campaign takes effort. Sponsoring a consciousness raising Move Your Money event is time consuming.

Not much needs to be said about the standard forms of political participation. Voting on Election Day is a typical and well-understood example, and much ink has been spilled explaining why cynicism abounds.

None of these all-too-familiar forms of participation seems up to the challenge of creating the new values that protesters claim lie at the heart of

OWS. People say, for example, "Run your own candidates!" and the Occupy protesters respond, "But that system is broken." They say, "Help out the

unions!" and the Occupy protesters shrug because their concerns are not just those of organized labor. And so on, and so forth. Through it all, they

keep Occupying away.

Image: Reuters.

In Focus

In Focus

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you’re not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register. blog comments powered by Disqus