Must-read NCAR analysis warns we risk multiple, devastating global droughts even on moderate emissions path

Extended drought and Dust-Bowlification over large swaths of the habited Earth may be the most dangerous impact of unrestricted greenhouse gas emissions, as I’ve discussed many times (see Intro to global warming impacts: Hell and High Water).

That’s especially true since such impacts could well last centuries, whereas the actual Dust Bowl itself only lasted seven to ten years — see NOAA stunner: Climate change “largely irreversible for 1000 years,” with permanent Dust Bowls in Southwest and around the globe.

A must-read new study from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, “Drought under global warming: a review,” is the best review and analysis on the subject I’ve seen. It spells out for the lukewarmers and the delayers just what we risk if we continue to listen to the Siren song of “more energy R&D plus adapatation.”

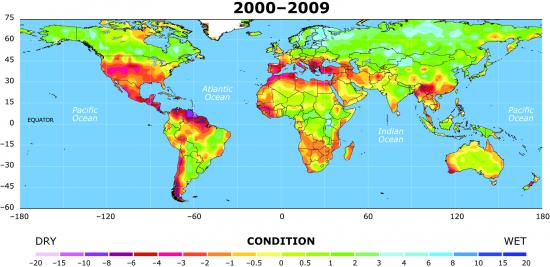

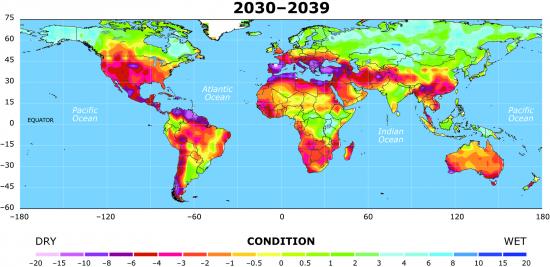

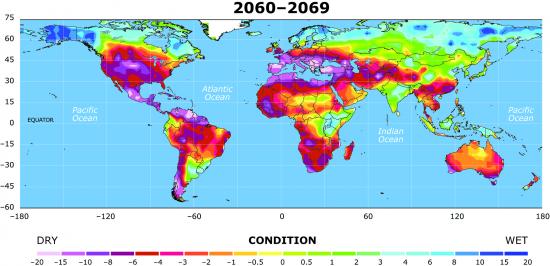

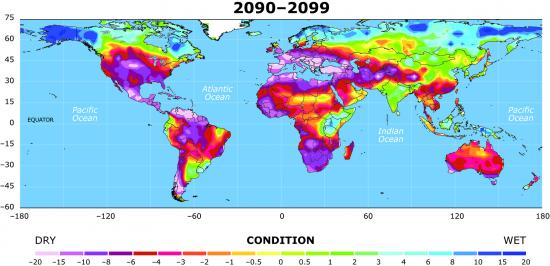

The NCAR study is the source of the top figure (click to enlarge), which shows that in a half century, much of the United States (and large parts of the rest of the world) could experience devastating levels of drought — far worse than the 1930s Dust Bowl, especially since the conditions would only get worse and worse and worse and worse, while potentially affecting 10 to 100 times as many people. And this study merely models the IPCC’s “moderate” A1B scenario — atmospheric concentrations of CO2 around 520 ppm in 2050 and 700 in 2100. We’re currently on the A1F1 pathway, which would takes us to 1000 ppm by century’s end, but I’m sure with an aggressive program of energy R&D we could keep that to, say 900 ppm.

Indeed, the study itself notes that it has ignored well understood climate impacts that could worsen the situation:

As alarming as Figure 11 shows, there may still be other processes that could cause additional drying over land under global warming that are not included in the PDSI calculation. For example, both thermodynamic arguments124 and climate model simulations125 suggest that precipitation may become more intense but less frequent (i.e., longer dry spells) under GHG-induced global warming. This may increase flash floods and runoff, but diminish soil moisture and increase the risk of agricultural drought.

That is, even when it does rain in dry areas, it may come down so intensely as to be counterproductive.

The study notes that “Recent studies revealed that persistent dry periods lasting for multiple years to several decades have occurred many times during the last 500-1000 years over North America, West Africa, and East Asia.” Of course, those periods inevitably caused havoc on local inhabitants. Further, this study warns that by century’s end, even in this moderate scenario, many parts of the world could see extended drought beyond the range of human experience:

The large-scale pattern shown in Figure 11 appears to be a robust response to increased GHGs. This is very alarming because if the drying is anything resembling Figure 11, a very large population will be severely affected in the coming decades over the whole United States, southern Europe, Southeast Asia, Brazil, Chile, Australia, and most of Africa.

Most important, unlike most earlier droughts over the past millennium, these super-droughts will hit a planet with a population approaching 10 billion — and they will hit multiple areas simultaneously, making it exceedingly difficult for countries to receive significant outside aid or for large populations to migrate.

And as I have discussed, future droughts will be fundamentally different from all previous droughts that humanity has experienced because they will be very hot weather droughts (see Must-have PPT: The “global-change-type drought” and the future of extreme weather).

One can talk about adapting to this cataclysm, but fundamentally we are really talking more about misery and triage than what most people think of adaptation (see Real adaptation is as politically tough as real mitigation, but much more expensive and not as effective in reducing future misery: Rhetorical adaptation, however, is a political winner. Too bad it means preventable suffering for billions).

For media coverage of the NCAR report, see

- MSNBC: “Future droughts will be shockers, study says 1970s. Sahel disaster will seem mild compared to areas by 2030s, models project.”

- AFP: “Much of planet could see extreme drought in 30 years: study”

- Reuters: “Some of the world’s most populous areas — southern Europe, northern Africa, the western [2/3rds of the] U.S. and much of Latin America — could face severe, even unprecedented drought by 2100, researchers said Tuesday.”

While this study has received deserved attention, the UK Met Office came to a similar view four years ago in their analysis, projecting severe drought over 40% of the Earth landmass by century’s end (see “The Century of Drought“).

Also, “the unexpectedly rapid expansion of the tropical belt constitutes yet another signal that climate change is occurring sooner than expected,” noted one climate researcher in December 2007. A 2008 study led by NOAA noted, “A poleward expansion of the tropics is likely to bring even drier conditions to” the U.S. Southwest, Mexico, Australia and parts of Africa and South America.”

In 2007, Science (subs. req’d) published research that “predicted a permanent drought by 2050 throughout the Southwest” “” levels of aridity comparable to the 1930s Dust Bowl would stretch from Kansas to California. And they were also only looking at a 720 ppm case. The Dust Bowl was a sustained decrease in soil moisture of about 15% (“which is calculated by subtracting evaporation from precipitation”).

Because this subject is so important, I am going to repost NCAR’s release, “Climate change: Drought may threaten much of globe within decades:

The United States and many other heavily populated countries face a growing threat of severe and prolonged drought in coming decades, according to a new study by National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) scientist Aiguo Dai. The detailed analysis concludes that warming temperatures associated with climate change will likely create increasingly dry conditions across much of the globe in the next 30 years, possibly reaching a scale in some regions by the end of the century that has rarely, if ever, been observed in modern times. Using an ensemble of 22 computer climate models and a comprehensive index of drought conditions, as well as analyses of previously published studies, the paper finds most of the Western Hemisphere, along with large parts of Eurasia, Africa, and Australia, may be at threat of extreme drought this century.

In contrast, higher-latitude regions from Alaska to Scandinavia are likely to become more moist.

Dai cautioned that the findings are based on the best current projections of greenhouse gas emissions. What actually happens in coming decades will depend on many factors, including actual future emissions of greenhouse gases as well as natural climate cycles such as El Ni±o.

The new findings appear this week as part of a longer review article in Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. The study was supported by the National Science Foundation, NCAR’s sponsor.

“We are facing the possibility of widespread drought in the coming decades, but this has yet to be fully recognized by both the public and the climate change research community,” Dai says. “If the projections in this study come even close to being realized, the consequences for society worldwide will be enormous.”

While regional climate projections are less certain than those for the globe as a whole, Dai’s study indicates that most of the western two-thirds of the United States will be significantly drier by the 2030s. Large parts of the nation may face an increasing risk of extreme drought during the century.

Other countries and continents that could face significant drying include:

- Much of Latin America, including large sections of Mexico and Brazil

- Regions bordering the Mediterranean Sea, which could become especially dry

- Large parts of Southwest Asia

- Most of Africa and Australia, with particularly dry conditions in regions of Africa

- Southeast Asia, including parts of China and neighboring countries

The study also finds that drought risk can be expected to decrease this century across much of Northern Europe, Russia, Canada, and Alaska, as well as some areas in the Southern Hemisphere. However, the globe’s land areas should be drier overall.

“The increased wetness over the northern, sparsely populated high latitudes can’t match the drying over the more densely populated temperate and tropical areas,” Dai says.

A climate change expert not associated with the study, Richard Seager of Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, adds:

“As Dai emphasizes here, vast swaths of the subtropics and the midlatitude continents face a future with drier soils and less surface water as a result of reducing rainfall and increasing evaporation driven by a warming atmosphere. The term ‘global warming’ does not do justice to the climatic changes the world will experience in coming decades. Some of the worst disruptions we face will involve water, not just temperature.”

Future drought. These four maps illustrate the potential for future drought worldwide over the decades indicated, based on current projections of future greenhouse gas emissions. These maps are not intended as forecasts, since the actual course of projected greenhouse gas emissions as well as natural climate variations could alter the drought patterns.The maps use a common measure, the Palmer Drought Severity Index, which assigns positive numbers when conditions are unusually wet for a particular region, and negative numbers when conditions are unusually dry. A reading of -4 or below is considered extreme drought. Regions that are blue or green will likely be at lower risk of drought, while those in the red and purple spectrum could face more unusually extreme drought conditions. (Courtesy Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews, redrawn by UCAR. This image is freely available for media use. Please credit the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. For more information on how individuals and organizations may use UCAR images, see Media & nonprofit use*)

A portrait of worsening drought

Previous climate studies have indicated that global warming will probably alter precipitation patterns as the subtropics expand. The 2007 assessment by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that subtropical areas will likely have precipitation declines, with high-latitude areas getting more precipitation.

In addition, previous studies by Dai have indicated that climate change may already be having a drying effect on parts of the world. In a much-cited 2004 study, he and colleagues found that the percentage of Earth’s land area stricken by serious drought more than doubled from the 1970s to the early 2000s. Last year, he headed up a research team that found that some of the world’s major rivers are losing water.

In his new study, Dai turned from rain and snow amounts to drought itself, and posed a basic question: how will climate change affect future droughts? If rainfall runs short by a given amount, it may or may not produce drought conditions, depending on how warm it is, how quickly the moisture evaporates, and other factors.

Droughts are complex events that can be associated with significantly reduced precipitation, dry soils that fail to sustain crops, and reduced levels in reservoirs and other bodies of water that can imperil drinking supplies. A common measure called the Palmer Drought Severity Index classifies the strength of a drought by tracking precipitation and evaporation over time and comparing them to the usual variability one would expect at a given location.

Dai turned to results from the 22 computer models used by the IPCC in its 2007 report to gather projections about temperature, precipitation, humidity, wind speed, and Earth’s radiative balance, based on current projections of greenhouse gas emissions. He then fed the information into the Palmer model to calculate the PDSI index. A reading of +0.5 to -0.5 on the index indicates normal conditions, while a reading at or below -4 indicates extreme drought. The most index ranges from +10 to -10 for current climate conditions, although readings below -6 are exceedingly rare, even during short periods of time in small areas.

By the 2030s, the results indicated that some regions in the United States and overseas could experience particularly severe conditions, with average decadal readings potentially dropping to -4 to -6 in much of the central and western United States as well as several regions overseas, and -8 or lower in parts of the Mediterranean. By the end of the century, many populated areas, including parts of the United States, could face readings in the range of -8 to -10, and much of the Mediterranean could fall to -15 to -20. Such readings would be almost unprecedented.

The PDSI in the Great Plains during the Dust Bowl apparently spiked very briefly to -6, but otherwise rarely exceeded -3 for the decade (see here). So the numbers projected by Dai are beyond catastrophic, the damage would be incalculable.

Dai cautions that global climate models remain inconsistent in capturing precipitation changes and other atmospheric factors, especially at the regional scale. However, the 2007 IPCC models were in stronger agreement on high- and low-latitude precipitation than those used in previous reports, says Dai.

There are also uncertainties in how well the Palmer index captures the range of conditions that future climate may produce. The index could be overestimating drought intensity in the more extreme cases, says Dai. On the other hand, the index may be underestimating the loss of soil moisture should rain and snow fall in shorter, heavier bursts and run off more quickly. Such precipitation trends have already been diagnosed in the United States and several other areas over recent years, says Dai.

“The fact that the current drought index may not work for the 21st century climate is itself a troubling sign,” Dai says.

- Absolute must read: Australia today offers horrific glimpse of U.S. Southwest, much of planet, post-2040, if we don’t slash emissions soon”

- “Australia faces collapse as climate change kicks in”: Are the Southwest and California next?

- Dust Bowl-ification hits Eastern Australia “” next stop the U.S. Southwest.

Also, Bryan Walsh has a good piece on EcoCentric, “Water: Lake Mead Is at Record Low Levels. Is the Southwest Drying Up?“

FRONT

FRONT

People read:”Sometime in the past there were alligator swimming in Antarctica ..”

And people think, of a modest climate but tend to overlook the period of abrupt climate shift -duration.

First the northern ice vanishes followed with abrupt methane spikes – devastation throughout the entire northern hemisphere! Later a similar scenario will get rid of the southern planet side. A total reboot of the planetary system is possible. There is not a safe place and only anarchy awaits in these scenarios we are about to enter. The survival of the entire human species is at stake. Those remaining face several other scenarios originating from the chaos unleashed. You cannot plan for this, because of the extended timeframe.

I’m not seeing those additional two maps (just a red X), but note that for now the study itself can be viewed without charge.

The national security aspect of this is frightening. It would give new meaning to the phrase “food fight.” The oil wars will seem tame. And you have to add in what is likely to happen to fish production with coral bleaching and acidification.

A question. The paper has only one author, Aiguo Dai, who works at NCAR. So, is this just his paper, or does it represent an official assessment by NCAR?

See: http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/adai/myself-dai.html

We already know things will be bad by 2060, by which time many of us would be dead even without climate change. I would really like for climate scientists to shift their focus toward better and more detailed climate change forecasting in the 2015-2050 time frame.

I understand peak oil observers are predicting oil production will be in decline by 2012 to 2014. This, combined with climate change, puts social chaos years, not decades, away.

Good questions from #4 Wonhyo;

Many of the most dire predictions from the IPCC and others begin around mid century- when most of us here will be gone. What truly intrigues me is what about this decade- what shall we see by 2015, 2020?

And in the 2020s to 2030- it seems that a high emissions scenario is now likely to 2030- so it seems the most severe predictions are likely to take place. By 2030 C02 levels at 415-420ppm–well over 400ppm- more arctic melting could present us with challenges that have been thus far too conservative in their feedback’s.

It would be interesting to see what impacts we shall see over the next 20 years.

Only partly joking, it happens in March 2012.

That warm may well give rise to more significant SLR as well.

Shocking stuff, indeed.

Joe, is there any way to create an easily accessible page of recent publications such as this one and the recent articles describing carbon dioxide as a thermostat? I know they are in your posts, but I sometimes have difficulty finding the references later when I can then access the full text documents.

[JR: You can search for them. I might set up a sidebar.]

David B. Benson, please let me in on the joke. Why March 2012? I would have thought December 22, 2012.

In the main essay Joe wrote:

Undoubtedly will greatly reduce agricultural output, but delayers can take comfort in this being the major negative feedback of the carbon cycle. Drought makes it easier to lose soil to the wind, flash floods cause major soil erosion, then expose rock and gradually lead to the mineralization of atmospheric CO2 over the next 100,000 years.

catman306 — Beware the Ides of March.

Why December 22, precisely?

This is a fascinating study.

Joe – the one factor that seems to be discounted here is the overwhelming likelihood (not just possibility) that we will hit serious oil depletion (the downslope of peak oil) by 2015 and this will massively hurt our economy for decades. The result of this will be decreased emissions. How do you think this will play out, and what have peer-reviewed studies of this determined.

That is, does the data suggest that after 2015 we will somehow remain on the high-emissions trajectory? (I can’t see how, though I can see that maybe two decades out we could bring up enough new coal generation to supplant some of that oil and our emissions would rebound a bit.)

[JR: Peak conventional oil doesn't save us -- it doesn't even help unless we voluntarily abandon unconventional oil. Also, these studies don't have carbon cycle feedbacks in them (e.g. tundra defrosting).]

[JR: Peak conventional oil doesn't save us -- it doesn't even help unless we voluntarily abandon unconventional oil. Also, these studies don't have carbon cycle feedbacks in them (e.g. tundra defrosting).]

Joe – Thanks for the reply. Are there peer-reviewed studies that integrate current peak oil projections (say the recent UK industry report, the German military report, the Kuwait University report, Hirsch et al., etc.) into emissions models for climate change projections? I’d be interested in reading them.

Regarding unconventional oil: I agree partly, but the analysis I’ve read – take Hirsch’s 2005 study among others – suggests that the catastrophic impact peak oil will have on our economy will make it financially hard to make the massive investments we’d need to bring sufficient unconventional oil production online to replace the conventional supply we’d be losing. So I am by no means in the camp that says peak oil will resolve the emissions problem, but rather wondering what it will do to the trajectory in empirical terms.

BR — Unconventional oil sources have bad EIEO ratios, so the CO2 produced goes way up in trade for continuing to have conventional transportation fuels.

BR peak oil is not going to save us, burning much, much less coal just might though.

Joe, thanks for highlighting this important paper!

David – Agreed, but the financial investment required in them (which is in part the cause of the bad EROEI ratios) is why it’s possible they may not be developed at all if we’re in economic dire straights, which is likely. Plus the unconventional sources are unlikely to be scaled up to near the production levels of conventional sources. (I.e. there’s some fairly low limit – probably in the ~5 mbd range from what I’ve seen – on the rate we can extract from Canadian tar sands; median case production declines after 2015 are projected to be around 4% per year, which at our current rate would eat up most of that tar sands production at its max in one year. Then the following year we’d have to find the equivalent of that much production and scale it up in a single year.)

Mapleleaf – I agree. We need to deal with our emissions – especially coal emissions – regardless of peak oil. However, I think it’s important for us to understand the emissions path we’re likely to be on given that peak oil is likely to hit us very soon.

The problem is, if peak oil hits, oil prices will rise, making unconventional oils more economic to exploit. So I do not think that peak oil will slow our consumption of oil in any way.

Good catch. I like the format and style of the report, it’s readable but not a tome.

The map of 2000-2010 would be a nice graphic for future stories. The brown/red regions coincide with many recent, continuing droughts. That graphic will help readers realize there are connections between serious local problems and global warming.

David – That’s true up to a point, but only if depletion is very mild. Anything like the depletion rates that most are projecting (above 2% per year) will have such a massive impact on the economy that there won’t be the financing available for big unconventional oil projects.

The “American Great Plains Desert of 2060s” projected is surprisingly north and east, IMHO. Another things that surprise me are the severity projected at Western Mediterranean and N Australia. But hey, it’s a model (somewhat distressed :-D). Who lives long, sees.

I have no idea how Western Australia will be livable 30 years time. Food and other necessities have become terribly expensive in Western Australia over the past 15 years, and the south-west has just had the driest 12 months on record, with all models showing it will get far worse in years to come. We are running out of water here already – ground water is being taken far quicker than it can be replenished. Everything burns here in the summer, I’ve never known it to be as intense as the past 2 or 3 years. Moving to central-eastern Tasmania seems the best option at the moment.

http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/drought/drought.shtml

Interesting that two of the least affected areas are India and China…

David Benson, December 22, 2012 (winter solstice) is the day the Mayan calendar ends. Some say it marks the end of our world. Five years ago I thought it might be mark the day that the Greenland Ice Cap slips into the sea. That’s still a remote possibility and it’s about 8 weeks after the 2012 presidential election.

will this drought be before or after the plague of locusts ?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hJQ18S6aag

Canada will sure have a long wall to build to keep the illegal American immigrants out.

#23 good catch.

Model doesn’t seem to account for glacier losses.

These will be very, very hard on China and India.

Another great article with devastating implications. (greatly informative; devastating implications of devastation.)

Looking at the U.S. portion of the 2060 map, a friend remarked that it apparently ignored the effect of the Rocky Mountains. I guessed the grid was too coarse to pick up surface features like that.

(BTW: I think the MSNBC headline should read “Future droughts will be shockers, study says. 1970s Sahel disaster will seem mild compared to areas by 2030s, models project.”

I see a 2.2 ppm CO2 increase this year and given the fact China intends to expand its auto market to about 40 million vehicles in the next ten years, CO2 concentrations in 2030 will exceed 440 ppm…20 years out. Game over.

Glad to see a new focus on peak oil in this blog. It will be hastened by China’s rapid increase in oil demand thus driving up the price…unconventional oil will quickly follow for the few projects in the western US that are near the deployable stage.

In the 70s, I did a lot of research and activism on Rocky Mountain oil shale. A one million barrel per day oil shale retort industry would move as much material as the coal we transport today. Not an answer to oil shortages but a money machine for the investors.

John McCormick

I agree with Wanjo #5 and Peter M#6 that local, already observable effects and short term projections should be more widely publicized.

A friend of mine has been doing some calculations documenting the observable increase in extreme rain events for our Midwest area, and we’ve discussed the potential effects of higher night time temps on plant growth.

Apparently, in some circles, climate disruption is a given and short-term risks are already being planned for: Insurance companies are putting climate change into easy-to-understand expense projections (and investment/profit opportunities). Swiss re has just released a report. See AFP report here:

http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5j8Bk_c_uNEPNO_IoEqKLH2y6aJLQ?docId=CNG.be1430cf7ec438b63479d0e3742332c8.ad1

Bloomberg report here: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-10-20/u-s-gulf-coast-faces-350-billion-in-climate-damage-by-2030-study-shows.html

Of course–weirdly–the recommended mitigation measures don’t seem to include reducing emissions!!!

LOL Ides of March, 2012

comic relief: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y54FRMedT_s

#28 John M

Thanks for your depressing CO2 outlook @ 440ppm in 2030

again we are doomed-

And on the other hand, we’re up to tropical cyclone Richard already and we may even get to Sally or whatever name is coming next. So far this year despite the extremely active Atlantic hurricane season no really massive storms have made landfall in North America so people haven’t paid much attention — although there has been serious flooding in the Rio Grande valley and elsewhere. It takes a helluva lot to get people to notice it seems.

Recent stories about the 1930′s constructed Lake Mead reaching its all time low level since first filling mention the SW U.S. ongoing drought. The Colorado River has recently been running at 80% of historic flows and this isn’t quite enough to keep up with evaporation from Lakes Mead and Powell and withdrawals for irrigation and drinking.

However, I’ve seen nothing to indicate an ongoing drought in the region. I know of no weather pattern that would indicate the current climate is nothing other than what can be normally expected for the region. I think 80% flow for the Colorado is the new normal and is only going to continue to decrease. I believe this is global warming in the SW U.S, here and now.

I think even with conservation, one of the reservoirs is going to have to be drained. Lake Powell most likely as it is strictly a water storage and power generating reservoir, and without water to store, it serves no purpose that can’t be replaced with some form of solar or wind generators.

Disagreement?

http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/10/18/lake-mead-hits-record-low-level/?scp=1&sq=Lake%20Mead&st=cse

http://water-data.com/

I think the important part is the message that we will have “devastating global droughts even on moderate emissions path.” DEVASTATING GLOBAL DROUGHTS – so the droughts will be much worse than we are already experiencing now and this is a prediction based on moderate emissions. We are certainly not moderating our GHG emissions.

With increasing population the need for an increase in all vital resource production is necessary to maintain a reasonable standard of living and it is not possible to name a single resource that does not require water to exploit it and to bring it to market. This is especially true with energy production. Water will not run from the tap without energy to deliver it and we produce very very little electricity that does not require water. Even water cooled solar plants will consume vast amounts of water. It is reported that these solar plants would use 2 to 3 times more water than coal power plants.

DOE says we must increase our energy production 40% by 2050 and they have quiet a few of these solar water hogs planned for the southwest US. And this is with the water level in Lake Mead only 8 ft from cutting Las Vegas off from water! Meanwhile, congress had mandated that DOE, in conjunction with the 2005 Energy Security Act, conduct a research program called the National Energy-Water Roadmap to determine just how we will be able to reach our energy requirements and not run out of water. DOE has withheld from public view the results of the final report that would present “a comprehensive research agenda to better understand the nation’s energy—water choke points and begin developing real world solutions.” DOE has declined to explain why the report has not been published. Is the truth about our water crisis too terrible to contemplate? Is the real Ponzi scheme the one that says we will have plenty of cheap freshwater to power our cities, run our economy as well as for washing and drinking?

DOE must make realistic plans for the future that take water scarcity into account. Plans not just for how electricity is produced but how the next generation of biofuels will be produced as well. We may have new solar plants in the Sonora Desert that are unable to make electricity by the time they are completed.

For the article about water scarcity, energy, and DOE’s failings:

http://www.circleofblue.org/waternews/2010/world/in-era-of-climate-change-and-water-scarcity-meeting-national-energy-demand-confronts-major-impediments/

I’m curious if anyone has an explanation for this… If the time of the dinosaurs had very high CO2 levels, and also a very active water cycle, and therefore spurred along all the vegetation that allowed the dinos to get so big, what’s the difference here? Is the difference that the CO2 levels we are headed for are not quite as high yet as the triassic/Jurassic, so the climate response is a little different, that is a drier heat on the continents?

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a doubter, just wondering where the models match up or meet.

“The maps use a common measure, the Palmer Drought Severity Index, which assigns positive numbers when conditions are unusually wet for a particular region, and negative numbers when conditions are unusually dry. A reading of -4 or below is considered extreme drought.”

I would like to see maps that use some absolute index of drought, rather than this index of whether conditions are unusually wet or dry for that region.

Notice that the first map shows that the Sahara Desert is currently relatively wet, with a rating of about +0.5 on the PDSI, while an absolute index would show that it already faces extreme drought. You obviously don’t need to get to -4 on the PDSI before you face extreme drought.

John -

Rocky Mountain oil shale.

” Oil shale the fuel of the future , always has been, always will be. “

Sue: most of the terrestrial earth was desert during the Triassic. Dinosaurs were big for reasons other than lots to eat. Read the recently published book Vanished Ocean by Dorrik Stow for a very good summary of the history of the earth’s condition.

If the 2060 projections bear out: there won’t be any increase in agricultural output from northern North America, most of the interior of North America will be desert with western forests only on mountain tops and along the Pacific Coast, and there will be no eastern decidous forest other than in extreme northeastern New Enland. This is disaster.

Sue in NH wrote: “I’m curious if anyone has an explanation for this… If the time of the dinosaurs had very high CO2 levels, and also a very active water cycle, and therefore spurred along all the vegetation that allowed the dinosaurs to get so big, what’s the difference here?”

I haven’t had time to check all these facts, so please feel free to correct my mistakes. This is my understanding: During the time of the dinosaurs both CO2 and oxygen were higher than today’s levels. High CO2 and water vapor account for the higher temperature and abundant plants. More oxygen allows bigger land animals: not only the dinosaurs, but dragonflies the size of large birds.

The meteor that hit 65 million years ago landed near the Yucatan Peninsula where the rocks held lots of sulfur and carbon. Dust and sulfur oxides released by the meteor darkened the sky, and so did soot from the many fires its impact debris set off in the high-oxygen atmosphere. There were years of cooling, which killed off many plant and animals. Then the dust cleared, but extra CO2 remained, keeping the temperature high.

After thousands of years rocks and new plants absorbed much of the CO2, and it fell gradually to the 180-280 ppm range where it’s been for the past few million years or so. That gave us the climate in which we evolved. Now we’re boosting CO2 relatively quickly, but we haven’t got to the point where steamy swamps that would make dinosaurs happy would appear.

catman306 — Oh, that too, that too.

Will Peak Oil prevent the worst of climate chaos? Very unlikely for two reasons that are rarely discussed.

1) A barrel of oil contains almost a decade of human energy in it according to Bill McKibben in his book “Eaarth”. At a dollar an day in wages that is equal to more than $2,000 per barrel. EROEI will not prevent us from burning most unconventional oil sources we know about.

2) As Hansen lays out in his book “Storms of my Grandchildren”, the climate doesn’t care how fast we burn the fossil fuels…all it reacts to is how much we shove up there in the coming centuries. If we burn them more slowly because they are expensive we still toast the biosphere. As he says we already know about more fossil fuel reserves than needed to push the climate into “Venus Syndrome”.

In short we know about enough fossil fuels to cook the biosphere; these reserves are economically viable compared to human labor alternative; burning them more slowly doesn’t stop climate chaos.

The only solution is to leave most of the fossil fuels we know about in the ground forever. This is especially true of unconventional oil and coal.

I would like to add that peak oil desperation can make the climate threat worse for a couple other reasons:

1) it causes people to be afraid which increases their reliance on the “known”

2) it removes the capital needed to switch the world’s infrastructure away from fossil dependency. This is the real battle for the future. If you have a fossil fueled car, heater, factory…you will be far more motivated to buy fossil fuel. I know people who can barely afford gas for their old cars but can’t possibly afford the capital to buy a new high-mpg car that would save them money in the long run.

One of the main climate issues globally right now is how to get the poor nations the money they need to buy cleaner infrastructure. They can do it themselves. Global negociations revolve around how much money wealthy nations will give to poor ones to transition away from essential but dirty infrastructure.

If peak oil becomes a major economic burden for wealthy nations then nobody will have the free capital to make the essential infrastructure changes.

Being poor and stuck with dirty fossil fueled infrastructure is not a “solution” to climate chaos. Far from it.

The study postulates that climate change may lead to a paradox of increased precipitation and yet drier soils.

There is evidence that this may already be happening.

Satellite data shows that global river flows increased 18% since the mid-1990s. Most of this increase was from increased precipitation.

http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/greenspace/2010/10/global-warming-river-flows-oceans-climate-disruption.html

Meanwhile, satellites have also recorded a decrease in soil moisture worldwide.

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn19565-water-cycle-goes-bust-as-the-world-gets-warmer.html

This matches up with studies for many areas showing increased rainfall overall but it coming down in fewer but much more intense events.

Fewer gentle showers replenishing the deep soil moisture — more downpours with flooding runoff — remaining soils drier overall.

One more thought on Peak oil and Drought.

A commonly advocated adaptation to increasingly expensive oil is to localize agriculture. I’m a fan for sure. The reasoning is that as oil gets more expensive keeping food affordable will require it be grown closer to where it is eaten to minimize expensive oil inputs. Makes sense.

However, climate disruptions can wreck havoc on agriculture in local regions. The more we rely on one area for our food the more we will care about a stable climate to grow it in.

As it becomes too expensive to replace a failed local crop with food from half a world away, we will care a lot more about things like drought indexes and rainfall patterns and soil moisture. Too bad we aren’t grasping the opportunity to mitigate these nasty trends now while there is still time.

Andy (35) -

The U.S. Drought Monitor indicates that there is virtually no drought, aside from just dryness, in the Southwest right now, although significant drought is developing across the Southeast; also, Hawaii has had extreme drought for most of the year.

http://www.drought.unl.edu/dm/monitor.html

Also of interest, where I live (St. Louis, Missouri), we are currently on track to have the driest October on record, although significant rainfall this weekend will probably prevent that from happening. However, last year had the wettest October on record, and by a good margin, and it was only two years ago (2008) when we had the wettest year on record (even though there were a couple dry months; this year has been near average so far). This appears to support more precipitation extremes.

Barry @43

Totally agree, and this is a point I have been stressing in my recent comments. The goal is to find a way to keep as much fossil fuel as possible in the ground, because unless we do this we are sunk, however many EVs and wind turbines we build.

For those expecting peak oil to save the day – it won’t. Coal-to-liquids technology is pretty simple and was used by Germany in WW2 to produce most of the fuel for its tanks and planes. It was also used by South Africa in the anti-apartheid years. It will be used again by the US, China and everyone else when the economics demand it.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_liquefaction

@ Barry

One last un-comforting peak oil thought: transformation to an economy not based on fossil fuels cruelly requires exceptional expenditure of fossil fuels now to construct the infrastructure for renewable energy later.

Yet it is of the utmost importance that those of us who do understand these things, climate change and peak oil, refrain from conveying the inherent despair involved with them when trying to educate others.

It is one area where we humanists could and should take a lesson from the great religious leaders of history; teaching hope in the face of a world that has forgotten it.

James, yes. David Orr talks about the difference between hope and optimism in Down to the Wire. Hope is key.

#47 Yes. Then why do NY Times and other reporters swallow whole the line the SW water hustlers give them that the current drop in lake Mead and Powell levels are due to an ongoing drought? These folks need to wake up.

Sue in NH, … If the time of the dinosaurs had very high CO2 levels, and also a very active water cycle, and therefore spurred along all the vegetation that allowed the dinos to get so big, what’s the difference here? Is the difference that the CO2 levels we are headed for are not quite as high yet as the Triassic/Jurassic, so the climate response is a little different, that is a drier heat on the continents?

The configuration of the continents was very different back then which would have its own considerable effect on climate. The closing of the Isthmus of Panama from 15-3 million years ago shutting off currents between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was a major factor in starting the current ice age cycle.

Water shortages are a “growing credit risk.”

“Investors Warned of Hidden Financial Risks of Water Shortages

An economic study released yesterday on ongoing and worsening water shortages in municipalities from Georgia to California is sending a warning signal to the investment community and highlighting the link between environmental and financial security.

Called The Ripple Effect, the study warns investors of the hidden risks embedded in bonds backing public water utilities and municipal power plants, increasingly vulnerable to water shortages due to climate change.

About 4 in 5 Americans get their water from public water utilities, and public power utilities provide electricity to 45 million people. The two industries are closely linked: power plants are responsible for 41% of national freshwater withdrawals, while water companies depend on electricity to transport water from reservoirs to homes.

“Investors should treat water availability as a growing credit risk,” said Mindy Lubber, the President of Ceres, in a news conference. “Ample, long-term water supplies are not a guarantee, and (they are at risk) in many parts of the country.”

http://www.reuters.com/article/idUS8272645120101022