Researchers must take time to listen to what politicians want. To have an impact on policymaking, we must try to marry our research interests with political agendas and manifestos, writes Herryman Moono.

Researchers must take time to listen to what politicians want. To have an impact on policymaking, we must try to marry our research interests with political agendas and manifestos, writes Herryman Moono.

In my introduction to the International Growth Centre, I was asked with fellow economists what I hoped to see in my future, say, where would I be after ten years of growth oriented research. I stated that if we are to be relevant in the ten years of our operation, we should be irrelevant in our 11th year, for if after ten years we are still facing the same problem and claiming to be guiding policy aimed at solving that problem, then we have been irrelevant for ten years!

The relevance of any development oriented research at any particular time aimed at addressing a particular problem lies in it becoming irrelevant after policy has been implemented. As absurd as it might sound, I strongly feel this is the way to think: The relevance of our work in development research must dissipate with time, this would be the only signal that we have delivered and are moving on.

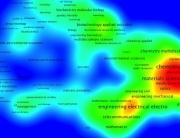

Developing countries have provided great opportunities for research in all spheres of academia: From the natural sciences to the social and behavioural sciences. But after decades of immense studies on African growth and development, most African countries’ growth remains subdued, and research continues.

With all the documented advice from ‘expats’ in respective fields of growth and development, from consultancies, national and international think tanks and indeed local resource personnel, we seem to have failed to solve the puzzle of growth and development for most parts of the developing world. My experience so far suggests that perhaps we have not taken time to listen to what the politicians want. Perhaps we have not persuaded them enough to buy into our policy agenda, which, unfortunately we may have formulated without even taking a glimpse into their political agenda or indeed party manifestos, through which they reign.

A classic case of the need to get closer to policy makers came during a meeting with the Vice-President of Zambia, Dr. Guy Scot, a Cambridge trained Economist. After our brief of our growth research work in Zambia, the vice president wondered why we have not ventured into research looking at employment creation. Jokingly he stated that even Keynes’s classic work was on the general theory of employment, so why were we not helping the government create more jobs for the people given on country constraints by researching in that area? Valid question indeed!

That encounter could perhaps explain why academics and researchers feel that their works and advice are not adhered to: Perhaps they do not answer the questions the policy makers are asking. Sifting through government departments, one will be amazed at the amount of literature and briefs addressing diverse development concerns, accumulated over the years, yet still facing the same questions. In my view, I may naively claim that most of developing countries’ problems may have already been solved on paper; operationalisation of those proposed solutions should be the next ideal step in development policy research.

However, we cannot move into implementation and operational guidance if our works are not aligned to the thinking of policy makers. We need to get as close as possible, our policy must be sold in such a way that while maintaining the research rigour, it provides clear directions with tradeoffs clearly marked. We must, however, guard against inclining to strict academic research for policy for most policy recommendations or indeed papers that have influenced policy in my country have never made it to a high profile journal.

So therefore, what is our relevance now if later we will still be faced with the same challenges we ought to have had solved earlier? For once, we should aim for and accept an irrelevance phase in our development research work, unless of course, we are merely doing academic exercises disguised as development policy.

Surely if you only do research that is ‘relevant’ to policymaking you are accepting that policymakers must have all the right questions. There is a clear role of researchers to identify issues and problems that policymakers and politicians are not considering. The pressure from donors (and capitulation of researchers and academics) to focus on demand driven research is, in my view, dangerous and likely to make all research irrelevant. It is transforming researchers into consultants, de-skilling them by focusing their attention on short-term studies and analyses, responding only to inflexible terms of reference.

This is a shame: relevance, I feel, is becoming a dangerous word. It assumes that anything more than one step away from policy is irrelevant. Try to provide sound economic policy advice without developing new datasets, trying out a few theories on new data, exploring new concepts and ideas… it will be poor advice, if you ask me.

Dr. Scott and Zambia will probably be better served by more ideas about employment presented in a great manner of ways and media than a single policy focused consultancy. They will have choice and the opportunity to debate the policies that are best for them.

Enrique,

To assume that politicians do not know what they ought to do for their electorate is one of the gravest assumptions most ‘policy’ researchers have made. Note that this is from my developing country experience, Zambia, so may not be relevant to other regions of the world. Indeed, you rightly say the need for researchers to identify the issues politicians are not considering. Through an experiences researcher’s lenses you may note serious problems which, unfortunately, may not be deemed so by the politician, who, alas, decides what is done and not. In this case, your work will make it to Econometrica or any other prestigious journal but fail to be of relevance to policy, right? I am glad to note that all demand driven research will be irrelevant, of course, ultimately it should be, and that is my argument. Of course the relevance in academia should not be compromised.

Most politicians are faced with serious trade-offs, and may be tempted to pursue short team goals which please the present population, they are the voters anyway, than the future generation which does not vote currently. I strongly believe taking note of such in our research and policy will be invaluable if we are to have any impact. And by this I mean employment creation, poverty reduction,etc.

If you may, consultancies rather than academic research has had the greatest impact on policy in this part of the world, for the simple reason that it is user-friendly and plain, by this I mean easy to administer in the eyes of the politician, whom you may claim to be an untrained amateur in strict academia.

Variety of policy ideas presented to policy makers may sound ideal, but its not. He/she has no time to window shop, he/she has a fixed term of office on which to leave a legacy of having ‘achieved’ results, not accumulated research papers that purport to answer the nation’s problems.

My note therefore, is that there is a misalignment in agenda: The researcher wants to have as many research papers as possible; the politician wants only those that can have impact, and they are needed quick, unfortunately. Dub this as the need for the ‘relevance of irrelevance in policy research’.

[...] Herryman Moono has written a post for the LSE Impact of Social Sciences Blog that advocates for demand-driven research, the new comfort zone for many researchers and programmes. He refers to that old phrase that development workers like to repeat to themselves and anyone willing to listen: we are working ourselves out of our job. I’ve never quite liked it. To begin with, we all know, deep down, that the world will not rid itself of poverty certainly not in our lifetime: our jobs are safe. But most importantly, for researchers, this is a ridiculous statement. Research is valuable for its own sake. A society that thinks is a better society than one that does not. Even if all the research undertaken is irrelevant to policymaking this would be better than having no research at all. [...]

[...] Our research must eventually become irrelevant: this is how to prove we had an impact on policymakin…. [...]