As a growth officer in my early career with the mad men and women of McCann Erickson, my mom could never quite grasp what I did for a living. But, when we pitched, won and delivered the phenomenon now globally known as Priceless for MasterCard, she could finally brag to her friends at my Aunt Rose’s kitchen table. From the moment the very first television commercial appeared (You remember it, right? “Two tickets: $28. Two hot dogs, two popcorns, two sodas: $18. One autographed baseball: $45. Real conversation with 11-year-old son: Priceless.”), Mom told practically anyone who would listen that I wrote and executed the entire campaign single-handedly. My role, in fact (promise not to tell her) was that of the Pitchman.

In one of the industry’s most hotly-contested advertising accounts, dozens of agencies’ pitches were winnowed down to two contenders. In a surprising twist, MasterCard declared that the agency with the highest score in consumer testing would win. The heart-wrenching result: Our Priceless campaign did not test well. In an act of courage, and confidence, the MasterCard team awarded us the business anyway. When I asked Larry Flanagan, who went on to become MasterCard’s celebrated CMO, about their decision to award us the business for the Priceless campaign, he said, “We bonded because McCann Erikson understood the deep desire of the MasterCard customer, but they understood MasterCard’s deep desire, too.”

We all make pitches every day — for that highly-prized account; to a client who’s reluctant to accept your scary proposal; for a skeptical CFO to loosen the purse strings; or for a wary new team to believe in you. Here’s what I’ve learned about winning pitches like these:

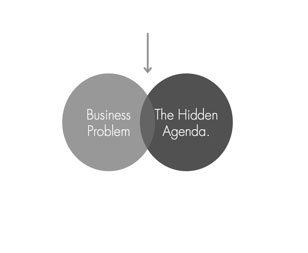

1. You need to understand that behind every decision lies a hidden agenda.

There are no magic tricks or hypnotics to persuade people to do what you say. Rather, behind every decision the average person makes to buy something — whether a product or service, your argument or an idea — is an unspoken emotional motivation. I call this the hidden agenda. Tap this, connect to it — and you will have people saying yes.

2. You need to do your emotional homework to find the hidden agenda.

To find the hidden agenda, you need to identify your audiences’ wants, needs and/or values. Too many pitches are lost because the people undertaking them think — erroneously — that the business matters at hand are the only relevant issue. Deep desires, often unspoken — like the desire to be recognized, to feel appreciated, to create something, to be admired, to lead, to feel safe and secure — are fundamental to any business decision. The business issue and the hidden agenda are intertwined.

For the MasterCard pitch, in fact, two parallel hidden agendas were at work — MasterCard’s agenda, and the agenda of MasterCard customers. MasterCard’s hidden agenda was a desire to finally score a victory over Visa, but there was a sense that it would be very difficult to achieve. The MasterCard customer’s hidden agenda: to be good people, buying good things, for good reasons.

A hidden agenda falls into one of three categories:

Wants are about people viewing their circumstances through the lens of ambition and confidence. For example, when pitching to a Wall Street titan some years back, we determined the following want: “I want people to recognize me for having created a financial services powerhouse.”

Needs are about viewing circumstances through the lens of fear or concern. The need we uncovered at the core of the MasterCard pitch was: We need to score a victory over Visa in the marketplace, and in doing so be famous for it… but we’re not so sure we can.

Values are about people viewing the world entirely through the lens of their belief systems. The key insight that led to the development of the Priceless campaign was in the value system of our target audience, namely people who believed they were good people buying good things for good reason, and that it was not possible to put a price on things like family and life experiences.

3. You need to connect yourself to the hidden agenda.

You win the pitch when you link what I call your leverageable assets to your audience’s hidden agenda. Your leverageable assets are:

Real Ambition: This is your intention to create something good where nothing existed before. In a wonderful pitch for South African Airways, the real ambition was based on a shared aspiration for a new South Africa, where South African Airways would be a proud, visible symbol of a new, diverse nation.

Your Core Abilities: These are the special abilities you possess at the core of your being that separate you from others. For those of us at McCann who were in pursuit of the MasterCard campaign, it was our fiercely competitive winners culture. As Larry Flanagan pointed out, “Yes, we honestly believed that MasterCard could win with McCann.”

Your Credo: These are the values and the belief system to which you subscribe, and/or a shared behavior and code of ethics that you’re working within. A good example is when Horst Schulze from Ritz Carlton summed up their credo with the following sentiment: We’re Ladies and Gentleman Serving Ladies and Gentleman.

Your Real Ambition is used to connect to the your audience’s Want, creating a shared vision of what the future will become. The South African Airways pitch was won on the basis of a shared ambition of presenting the airline as a symbol for what the entire nation could become. The pitch team summed up the sentiment in a short film — a photo essay of the mosaic of the new south Africa, with the strains of a beloved Thula Mtwana lullaby, all leading up to the tagline, “We’re South African.”

Your Credo is used to connect to the client’s Values, defining a belief system that you and your client share. A pitch for Marriott International was won on the basis of a shared value system, coined, The Sprit to Serve.

Your Core Ability is used to connect to the client’s Need, because you have something special that solves your client’s needs. McCann won the MasterCard campaign through a collective desire and ability to win against an entrenched competitor. Key to winning was applying the core ability of McCann — an intense and renowned competitive spirit, and a philosophy that every competitor’s vulnerability can be found. In fact, the very first sentiment of our presentation was a huge slide with the words Carpe Diem, and a powerful affirmation that MasterCard’s DNA aligned with a profound shift toward inner-directed societal values — and that this was indeed MasterCard’s moment.

4. You need to deliver like a litigator.

With this foundation, you can then create your argument, gathering all your facts and supporting evidence around the hidden agenda, which should be placed squarely at the center of your “case.” Then, you can create an exciting tale where your audience attains their deepest desire, not via business-speak, but with good old-fashioned storytelling to convincingly convey your pitch.

It may seem crazy for an ad man to assert that we really don’t “persuade” anybody to do anything. I believe, however, that pitches are won — and people are willing to follow you — not because you’ve twisted someone’s arm, but because people see that you understand them, that you’ve applied the time and the sensitivity to do so, and that you possess a special gift that can help them reach their heart’s desire. And that, my friends, is priceless.