We academics might love to be on the receiving end of applause from our peers but the singular focus on publications as the sole measuring rod of academic quality is deeply misguided. Harry van Dalen writes that our best minds are being tempted away from real-world policy and only a serious rethink of academic incentives will fill in the cracks that are beginning to show.

We academics might love to be on the receiving end of applause from our peers but the singular focus on publications as the sole measuring rod of academic quality is deeply misguided. Harry van Dalen writes that our best minds are being tempted away from real-world policy and only a serious rethink of academic incentives will fill in the cracks that are beginning to show.

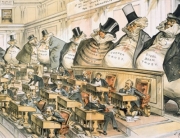

The Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson once expressed in quite clear terms what intrinsically motives academic economists: “In the long-run the economic scholar works for the only coin worth having – our own applause”. Although he described the motivation of economists, I dare say that all academics share this trait. Academics love applause from their peers, but the intellectuals among them are also quick to add that a beauty pageant is going to be a ludicrous exercise in ranking achievements. Still, this is what has happened to science over the past decades. The applause which served as an intrinsic motivator has turned into an extrinsic motivator. In order to gain tenure, grants and to have bargaining power with the dean it is paramount that one publishes ‘like hell’ in top journals to get the ball rolling to receive citations. Getting attention is the name of the game.

At present we are encountering the drawbacks of a singular focus on publications as the sole measuring rod of academic quality. Introducing the economist’s logic of carrot-and-stick in a creative industry is bound to lead to disappointments as psychologists can tell you and mistakes as discussed by the business economist Kerr (1975). He wrote the article On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B which argued that publications (A) are an imperfect measurement of innovative research (B). And rewarding A will generate a host of tactics to produce A but not necessarily B. Still this imperfect measuring rod is dominating hiring, promotion and tenure decisions. And to increase the power of the carrot, substantial individual cash bonuses have been introduced over to stimulate publication and incidence of this practice has increased substantially over the last ten years, especially in emerging economies like China and South Korea. Publishing in a journal like Nature or Science can earn you a bonus of a year’s salary. By making the monetary incentives so big, it must be a matter of time before we see unethical behavior arise.

The “publication bias” — the tendency to publish only confirmatory evidence — is another prominent effect. This bias has always been an issue in science, but the pressure to publish in academia might conflict with the objectivity and integrity of research, because — as Fanelli (2010) makes clear — “it forces scientists to produce ‘publishable’ results at all costs.” And at all costs could mean unethical behaviour of which fraud is the most extreme form. But journals themselves are also trapped in the game of attracting attention as some have been tempted to force potential authors to cite at least a number of articles from the same journal in order to increase the impact factor of the journal.

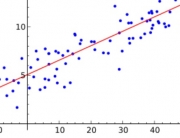

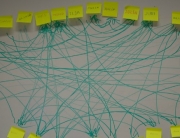

Amidst these developments one becomes curious how your colleague academics perceive the publication pressure. Do they feel the pressure is too high? And, if so, do they worry that it changes their manner of working? In a recent article, I and my colleague Kène Henkens, performed a survey among demographers on a worldwide scale, by sending a internet survey to the members of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, IUSSP (see our article in JASIST, early view). This survey has the advantage over comparable surveys in that its focus is international and it covers a social science that is itself a mixture of others. Besides demographers, sociologists, economists, geographers, historians, epidemiologists join the academic conversation (see for an overview of the entire survey our accompanying paper ‘What is on a Demographer’s Mind? in Demographic Research, 2012).

The survey reveals a number of effects. Scholars see both the pros of the so-called “publish-or-perish” culture (facilitating upward mobility) as well as the cons (excessive publication and uncitedness, less attention to policy issues, and the facts). Of these effects I only want to highlight one which seems central to the social sciences: the crowding out of attention to public policy issues.

The emerging picture is quite clear for economists: there is a divide between those who can publish in core academic journals and those who can’t do applied work. However, this divide is far stronger in countries where the publish-or-perish culture is clearly present. In their effort of getting tenure the focus is very one-sided certainly at Ivy League universities (see Klamer and Colander in their study The Making of an Economist): mathematical puzzle solving is praised, knowing the facts of what’s going on in the economy was seen by the large majority as unimportant (only 3 per cent considered it important). In the Netherlands and other European countries this tendency was far less pronounced twenty, thirty years ago, but recent work by David Colander suggest that European economists have become more ‘American’.

With hindsight, the preoccupation with high theory, or what economist Ronald Coase calls ‘blackboard economics’, may be one reason why economists were caught off guard when the credit crunch advanced. The best minds in economics were turning their attention to internal questions and models in which bank runs and sovereign defaults are out of the question.

Demography is a different story judging from our survey. Demographers were, from the start of their discipline in the 1930s, inclined to assist or serve policy making and some even go one step further and go out into the field (offering family planning or reproductive health services). Contrary to economists their research is for 99 percent empirical. Demographers love to gather data and policy making or giving policy advice is not a second-rate activity like as it is for today’s academic economists, but a respectable activity. However, we discovered that a high publication pressure is associated with less interest in policy and knowing the (population) facts is also considered less of an asset in becoming a successful demographer. Especially in the US and other Anglo-Saxon countries like the UK and Australia, the publication pressure is felt to be high by the large majority of demographers. Applied work is therefore also prone to becoming to be perceived as an activity “for those who can’t”.

What reinforces this is that non-Anglo-Saxon demographers who feel the pressure turn away from nationally oriented journals producing information that is potentially of value to local policy makers. The applause the academics seek is that of their peers who write in the top journals. It is a dilemma which the English or American researchers feel to a lesser extent. Writing in Dutch, French, or Swedish immediately shrinks your potential audience and because getting attention is what counts publishing in Dutch or German is then virtually the same as perishing. And so the best minds in a discipline are tempted to turn away from what’s going on in their country because in their eyes it is time ill spent. For a small and traditional science as demography, with its strong commitment to policy, these changes may be more than just a crack in the wall and repairing this crack will imply thinking more seriously about the incentives in academia.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the Impact of Social Sciences blog, nor of the London School of Economics

[...] recent LSE Impact blog piece about the steering effects of publication pressures highlights that inattention to policy on the part of academics is largely the result of [...]

[...] Publish-or-perish and attention to policy issues. [...]