- Book information

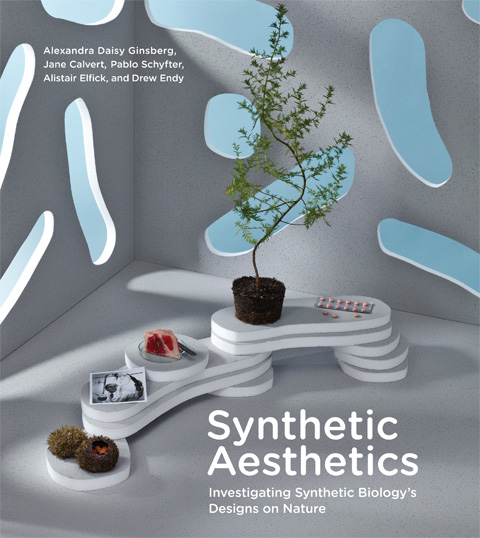

- Synthetic Aesthetics: Investigating synthetic biology's designs on nature by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Jane Calvert, Pablo Schyfter, Alistair Elfick and Drew Endy

- Published by: The MIT Press

- Price: $34.95/£24.95

Grand designs: xylem cells could help us make stronger buildings (Image: Dr David Furness, Keele University/SPL/Getty Images)

Grand designs: xylem cells could help us make stronger buildings (Image: Dr David Furness, Keele University/SPL/Getty Images)

In Synthetic Aesthetics, researchers and designers team up to present an exciting way of learning from nature

SYNTHETIC biology is not like other sciences. At its first big conference, held just 10 years ago at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the startling initial premise was that life is simply too complicated for biotechnologists to easily modify and that it would be better if engineers rebuilt life from scratch so the created organisms did exactly what was required.

The youthful enthusiasm that powered the field, and brought together engineers, biologists, computer scientists, physicists and biohackers, persists today. There have been a few major achievements, most notably last month's creation of a computer-designed yeast chromosome. And before that, the creation of the first synthetic cell.

The youthful enthusiasm that powered the field, and brought together engineers, biologists, computer scientists, physicists and biohackers, persists today. There have been a few major achievements, most notably last month's creation of a computer-designed yeast chromosome. And before that, the creation of the first synthetic cell.

Alongside this big science, researchers have built libraries of standard DNA code that controls different things inside cells. The dream is that one day it will be easy to design novel organisms using DNA as the programming language. Synthetic biology's headline-grabbing achievement is its annual International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition, which attracts hundreds of student teams to reprogram organisms. Last year's winners re-engineered the bacterium E. coli to recycle gold from electronic waste. At iGEM, the defensive attitude of biotech is replaced with one of turn up, take part, and talk.

These cultural roots may explain why some of its leading scientists took the unusual step of teaming up with artists and designers to create some fresh thinking. The result is the glossy Synthetic Aesthetics: Investigating synthetic biology's designs on nature. It is a freewheeling book with 20 authors and may irritate conventional scientists – some of the ideas were dreamed up while "performing a dance based on the myth of the Golem", for example. But it certainly explains the key ideas of the field and leads you to many lateral conversations about what it may become.

In the first few chapters, one central concern is what is meant by "design". An engineer might think of designing a bridge to a particular specification; a synthetic biologist of designing a microorganism with a new commercial application, pumping out green gasoline for example; but a real designer, a fashion designer, for example, is doing something else.

As artist Daisy Ginsberg puts it, design "is about possibility", the unimagined things that life could be. Synthetic biology, she writes, has been addressing "humanity's needs" – limitless fuel, for example – rather than "our needs as individual, diverse and complex humans". This is refreshing: worries about the separation between the top-down design of the future and those who must live with the designs are quite rare in science.

The book changes tone later as artists, designers and scientists pair up and spend four weeks working together. The results are surprising and one is quite amazing – when a plant biologist from the University of Cambridge, Fernan Federici, pairs up with David Benjamin, an architect working at Columbia University.

The focus was on form, not on learning from form in nature but from the "logic of nature"; Benjamin sees buildings that merely imitate a shell or leaf as superficial. In the lab, they studied plant xylem vessels – xylem cells make the tubes that transport water from the roots to the top of a tree. They wrote a program that describes the way the rigid skeleton emerges to strengthen the cell. Then they used the same "plant logic" in sophisticated architectural design software to model a supporting structure for a building.

Although we can't expect to see buildings designed by plants anytime soon – a pity given the average urban landscape – the key point is that the interaction led the collaborators to learn how biology computes "answers" to certain problems. This is a long way from the quest for endless gasoline and from seeing life as programmable parts, and shows how much the science of synthetic biology is willing to evolve. As the closing paragraph puts it, "we hope to help prevent synthetic biology simply following unimaginative and entrenched paths".

This article appeared in print under the headline "The logic of nature"

Alun Anderson is a consultant for New Scientist

- New Scientist

- Not just a website!

- Subscribe to New Scientist and get:

- New Scientist magazine delivered every week

- Unlimited online access to articles from over 500 back issues

- Subscribe Now and Save

If you would like to reuse any content from New Scientist, either in print or online, please contact the syndication department first for permission. New Scientist does not own rights to photos, but there are a variety of licensing options available for use of articles and graphics we own the copyright to.