Study: Better Observations, Analyses Detecting Short-Lived Tropical Systems

August 11, 2009

A NOAA-led team of scientists has found that the apparent increase in the number of tropical storms and hurricanes since the late 19th and early 20th centuries is likely attributable to improvements in observational tools and analysis techniques that better detect short-lived storms.

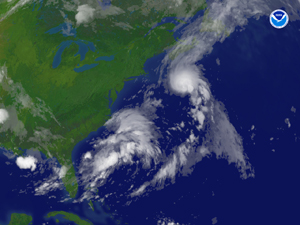

Short-lived Tropical Storm Chantal forms 210 miles south of Halifax, Nova Scotia on July 31, 2007.

High resolution (Credit: NOAA)

The new study, reported in the online edition of the American Meteorological Society’s peer-reviewed Journal of Climate, shows that short-lived tropical storms and hurricanes, defined as lasting two days or less, have increased from less than one per year to about five per year from 1878 to 2008.

“The recent jump in the number of short-lived systems is likely a consequence of improvements in observational tools and analysis techniques,” said Chris Landsea, science and operations officer at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center in Miami, and lead author on the study. “The team is not aware of any natural variability or greenhouse warming-induced climate change that would affect the short-lived tropical storms exclusively.”

Several storms in the last two seasons, including 2007’s Andrea, Chantal, Jerry and Melissa and 2008’s Arthur and Nana, would likely not have been considered tropical storms had it not been for technology such as satellite observations from NASA’s Quick Scatterometer (QuikSCAT), the European ASCAT (Advanced SCATterometer) and NOAA’s Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit (AMSU), as well as analysis techniques such as the Florida State University’s Cyclone Phase Space.

“We do not dispute that these recent systems were tropical storms,” said Landsea. “In fact, the National Hurricane Center’s ability to monitor these weaker, short-lived storms provides better warnings to mariners of gale force winds and high seas.”

According to Dr. Brian Soden, a professor at the University of Miami’s Rosentiel School for Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, “The study provides strong evidence that there has been no systematic change in the number of north Atlantic tropical cyclones during the 20th century.”

Co-authors Gabriel Vecchi and Thomas Knutson, both of the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, developed a sampling methodology to measure whether meteorologists missed medium- to long-lived tropical storms and hurricanes from the late 1800s through the 1950s. They found that about two of the medium- to long-lived storms per year were unaccounted for in the late 1800s. By the 1950s, forecasters missed less than one per year.

When the researchers discounted the number of short-lived tropical storms and hurricanes and added the estimated number of missed medium- to long-lived storms to the historical hurricane data, they found no significant long-term trend in the total number of storms.

The team also noted that the finding of no increasing trend in hurricane and tropical storm counts in the Atlantic is consistent with several recent global warming simulations from high-resolution global climate model and regional downscaling models.

"This new study is one piece of the puzzle of how climate may influence hurricanes. Although Atlantic storm counts overall have not changed, this study does not address how the strength and number of the strongest hurricanes have changed or may change due to global warming," noted Knutson.

Lennart Bengtsson of the University of Reading, United Kingdom, was also a research team member and co-author on the journal paper.

NOAA understands and predicts changes in the Earth's environment, from the depths of the ocean to the surface of the sun, and conserves and manages our coastal and marine resources.