|

|

| Home > About the NLM > News & Events > Press Releases > Visible Proofs | |

|

| |

| National Institutes of Health | National Library of Medicine |

| FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | Robert Mehnert • Kathy Cravedi |

| February 6, 2006 | (301) 496-6308 • publicinfo@nlm.nih.gov |

|

|

|

National Institutes Opens Health Exhibition

"VISIBLE PROOFS"

Forensic Views of the Body

|

Instruments used in President Abraham Lincoln's autopsy, April 15, 1865.

Credit: National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Smithsonian Institution High resolution image (1.7MB) |

|

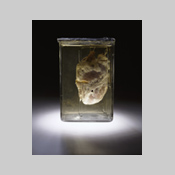

Kidney sliced open to show penetrating stab wound of a death attributed to homicide, New York, 1937. Credit: New York City Medical Examiner's Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. High resolution image (810KB) |

|

Illustration of a preliminary incision from: Post-mortem Manual: A Handbook of Morbid Anatomy and Post-mortem Technique, Charles Richard Box, M.D., London, 1910. Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (803KB) |

|

Mathieu Joseph Bonaventure Orfila, about 1835, Parisian medical professor now known as the "Father of Toxicology." He and others began to intensively study poisons and decomposition of bodies in the 1800’s. Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (840KB) |

|

A woodcut engraving of an insect from: La faune des cadavres; application de l'entomologie a la médecine légale [The fauna of the cadaver; the application of entomology to legal medicine], Pierre Mégnin, Paris, 1894. Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (762KB) |

|

The Telltale Blow Fly These black blow fly larvae were recovered in 1986 from the body of Sylvia Hunt, a murder victim found wrapped in a carpet on a Connecticut roadside. Credit: Courtesy of William L. Krinsky, M.D., Ph.D. High resolution image (732KB) |

|

Chart showing the spectra of different types of blood samples from: A System of Legal Medicine, Allan McLane Hamilton, M.D., and Lawrence Godkin, M.D., New York, 1894. Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (1.6MB) |

|

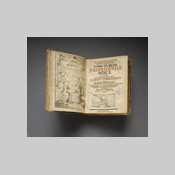

Title page from: Jurisprudentiae Medicae, 1740. Forensic medicine, also called "medical jurisprudence" or "legal medicine," emerged in the 1600s. As European nation-states and their judicial systems developed, physician and surgeons participated more frequently in legal proceedings. Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (1.8MB) |

|

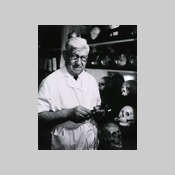

Milton Helpern, Chief Medical Examiner, New York City, poses for the cover of Modern Medicine magazine, April 12, 1965. Helpern joined the staff of the New York City Medical Examiner's Office in 1931. In 1954 he became the city's chief medical examiner. During his long career, he performed thousands of autopsies and was internationally recognized as an expert in forensic medicine. Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (732KB) |

|

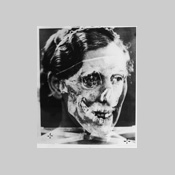

Superimposed photographs of Mrs. Isabella Ruxton and skull no. 2, 1935. Investigators laid a photo-transparency of this skull over Mrs. Ruxton's portrait to establish that the skull belonged to Mrs. Ruxton. Credit: University of Glasgow High resolution image (553KB) |

|

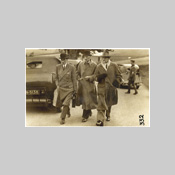

Policeman with a bag of human remains, 1935. Credit: University of Glasgow High resolution image (1.3MB) |

|

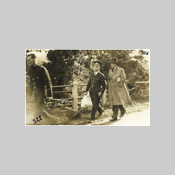

John Glaister Junior (left) the leading forensic investigator in the Ruxton case and two other men, Moffat, Scotland, about 1935. Celebrated as a landmark of forensic science, the Ruxton case fostered public faith in scientific crime investigation. Credit: University of Glasgow High resolution image (1.4MB) |

|

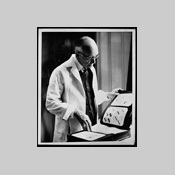

Dr. John Glaister, Jr., the leading forensic investigator in the Ruxton case, around 1960. Credit: University of Glasgow High resolution image (636KB) |

|

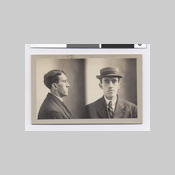

Early 20th century Bertillon Card. Police departments throughout Europe and the United States adopted Bertillon’s system of criminal identification in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The suspect's full-face and profile photographs appear on one side of the card; name, measurements, and other information are on the reverse. New York City Municipal Archives High resolution image (901KB) |

|

Photograph from: The Finger Print Instructor, . . . Based upon the Sir E. R. Henry System of Classifying and Filing . . . Frederick Kuhne, New York, 1940.

Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (962KB) |

|

Classification and Uses of Fingerprints, E.R. Henry, London, 1900. The Henry Classification System divides fingerprint records into groupings based on pattern types. The system makes it possible to search large numbers of fingerprint records by classifying fingerprints according to whether they have an "arch," "whorl," or "loop."

Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (1.6MB) |

|

Fingerprint card, Francisca Rojas (Individual dactiloscópica de Francisca Rojas), 1892 This card contains the fingerprints of Francisca Rojas, the first person convicted of murder through the taking of fingerprint evidence. Next photo shows the reverse side of the card. Credit: Dirección Museo Policial – Ministerio de Seguridad de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina Top image High resolution image (979KB) Bottom image High resolution image (2.2MB) |

|

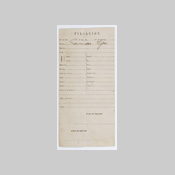

Juan Vucetich's personal file at the Buenos Aires Police Department, 1910. Vucetich was an Argentinian police official who devised the first workable system of fingerprint identification, and who pioneered the first use of fingerprint evidence in a murder investigation.

Credit: Direccíon Museo Policial - Ministerio de Seguridad de la Provincia de Buenos Aires High resolution image (1.6MB) |

|

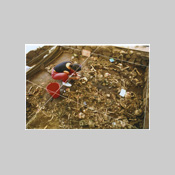

El Salvador, 1992. An Argentine forensic anthropology team worker helps excavate the site of the El Mozote massacre, where a Salvadoran army battalion killed about 800 villagers, almost half of them children. Credit: Courtesy of Daniel Muzio High resolution image (1.8MB) |

|

Ethiopia, 1990s. Doctors and personnel at the Black Lion Hospital in Addis Ababa work in the laboratory with members of the argentine Forensic Anthropology Team as part of their training in forensic anthropology. Credit: Stephen Ferry High resolution image (1.5MB) |

|

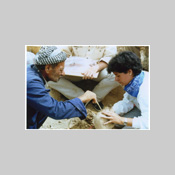

Iraqi Kurdistan, 1990s. Chilean anthropologist Isabel Reveco cleans a skull, helped by the father of two young men who were executed at Koreme. Credit: Mercedes Doretti/EAAF High resolution image (1.4KB) |

|

Mostly Murder, Sydney Smith, London, 1959. Dr. Sydney Alfred Smith was one of Britain’s most famous forensic pathologists.

Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (1.3MB) |

|

"Now Real Detectives Beat Sherlock Holmes," Edwin Teale, Popular Science Monthly, August 1931. Glowing newspaper and magazine accounts of forensic technologies, real and imaginary, fueled public support for scientific crime

detection.

Credit: Time4Media High resolution image (1.1MB) |

|

Inkless Stainless G-Men Fingerprint Set, No. 110, New York, 1937; Manufacturer: New York Toy & Game Mfg. Co.

Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (1.9MB) |

|

Clyde Snow, an American forensic anthropologist at the trial of the Argentinean junta, 1985. In a 1985 landmark trial, forensic testimony helped convict six of nine former Argentinean military junta leaders for the deaths of the "disappeared." The forensic investigation focused on the exhumation of human remains at individual graves, using archaeological techniques and laboratory identification systems. Credit: Courtesy of Daniel Muzio High resolution image (675KB) |

|

Exhumation at a cemetery in Argentina, 1988

Credit: Courtesy of Stephen Ferry High resolution image (1.8MB) |

|

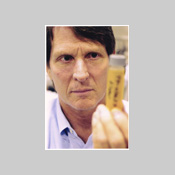

Brian Andresen with a sample vial, July 2004. Dr. Andresen had to find some way to detect minute concentrations of Pavulon in long-buried victims—a method

of teasing the drug out of decomposed tissue.

Credit: Courtesy of Anthony Pidgeon High resolution image (1.4MB) |

|

Vials and Evidence, July 2004. Dr. Andresen tested the soil around the caskets, and every type of embalming fluid used on the victims' bodies, to make sure there was no crosscontamination. Six exhumed patients tested positive for Pavulon. The proof was definitive—homicide had taken place. Saldivar had poisoned his victims. Credit: Courtesy of Anthony Pidgeon High resolution image (1.5MB) |

|

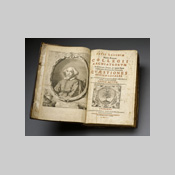

Title page from: Quaestiones medico-legales . . .5th ed.; Paolo Zacchia, M.D., Avignon, France, 1657. Medico-Legal Questions attempted to deal with every aspect of forensic medicine.

Credit: National Library of Medicine High resolution image (1.9MB) |

|

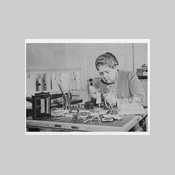

Mrs. Frances Glessner Lee at work on the Nutshell Collection, 1940s–1950s

Credit: Glessner House Museum, Chicago, Illinois High resolution image (1.3MB) |

|

Reinterment Ceremony for 1st Lt. Michael Blassie, formerly an unknown soldier. 1998

Credit: Courtesy of the Blassie Family High resolution image (1.5MB) |

|

Kirk Bloodsworth, 2003 Kirk Bloodsworth currently works for The Justice Project, a non-profit group that seeks legislative improvements that will prevent the American criminal justice system from sentencing innocent men and women to death for crimes they did not commit. Credit: Photograph by Dan Mullen, The Justice Project High resolution image (709KB) |

|

Heart of a 26-year-old man, perforated by a bullet, New York, 1937 Death attributed to homicide. Credit: New York City Medical Examiner's Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. High resolution image (943KB) |

Last updated: 07 February 2006

First published: 02 February 2006

Metadata| Permanence level: Permanent: Stable Content