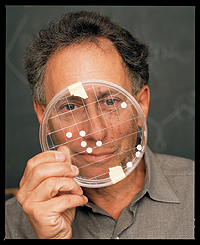

NIH Profile: Robert Langer, Sc.D.

Going for the ImpactRobert Langer is an engineer who wants to change the world. He's bringing industry along for the ride. Biorubber, microspheres, timed-release polymers, transdermal patches. Robert S. Langer, Sc.D., is a long-time NIH grantee who has had a hand in developing all kinds of innovative ways to engineer new tissue and deliver drugs to their precise targets in the body. Burn victims and patients with certain cancers and heart disease are better for it. "I'm an engineer. I try to solve problems," Langer says. His reasoned approach has yielded more than 500 patents; more than 40 products resulting from his work are now on the market or in human testing. "I want to see science do good, to help people," says Langer, a professor of chemical and biomedical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. The 55-year-old's success in that endeavor has earned him accolades from every corner. Discover Magazine named him one of the 20 most important people in medical technology. Forbes selected him as one of the 15 innovators worldwide who will reinvent our future. In 2002, Langer won the $500,000 Draper Award, engineering's version of the Nobel Prize. Throughout his career, Langer has received major support from the NIH. Today, he has grants from five NIH institutes. "The NIH has been the single biggest supporter of our lab," he says. "It enables us to do research. The money gives you the freedom to come up with the ideas you come up with—and those ideas can hopefully change the world in a better way." "The NIH's investment is amplified enormously by biotech companies," he adds. For example, the field that he helped launch, controlled drug delivery, includes things like transdermal patches used for nicotine replacement therapy, inhalation therapy being studied for diseases such as diabetes, and druginfused microchips. It is a $20 billion U.S. industry. In terms of health benefits, Langer claims, more than 10 million people in the United States alone use these kinds of systems. Early in his career, Langer realized that industry had to figure prominently if he wanted his inventions to reach the public. The private sector has the capacity and expertise to do final-stage testing, large-scale manufacturing, and obtain Food and Drug Administration approvals that academia does not. At first, he was swimming against the tide. Now he's seen as a visionary. He told the Boston Globe in a May 2003 article, "Some academics feel science should be pure, so they avoid interactions with companies. But when done well, I think the benefits are enormous—in treatments for disease, in new companies, in jobs." Langer has launched at least a dozen biotech firms and advises several more. More than 100 companies hold licenses to his patents. That means his discoveries reach the marketplace to help people. One example is the Gliadel Wafer. In the mid-1980s, Langer and Henry Brem, M.D., a neurosurgeon at the Johns Hopkins University who had worked with Langer in the lab of renowned cancer researcher Judah Folkman, M.D., created a dime-size wafer to deliver chemotherapy directly to a site in the brain where a tumor has been removed. The Gliadel Wafer became the first therapy in more than two decades to extend the lives of patients with a deadly brain cancer called glioblastoma. Langer and colleagues in June 2002 reported development of a new flexible plastic called biorubber. Biorubber can be impregnated with medicine or serve as a scaffold that can stretch and snap back like a rubber band, similar to human tissues such as the lungs' air sacs. The researchers are sharing samples with scientists around the world to test biorubber's utility in various settings. Langer's work has also made possible the drug-eluting stent, which became available to patients with heart disease in 2003. Used for patients with life-threatening narrowing of the arteries, one such stent is marketed by Johnson & Johnson and coated with a drug called rapamycin that is slowly released into the blood vessel to prevent restenosis—narrowing of the vessel that the stent was used to widen. He says he expects the new stents will save 100,000 lives. Sounds like Langer is making good on his goal of changing the world, thousands of patients at a time.  "I’m an engineer. I try to solve problems. I want to see science do good, to help people." "The NIH has been the single biggest supporter of our lab. It enables us to do research. The money gives you the freedom to come up with the ideas you come with—and those ideas can hopefully change the world in a better way." Robert Langer,

Sc.D. This page was last reviewed on

August 15, 2007

.

|