Midway Field JournalMarc Romano, Wildlife BiologistEvery day is something different! - March 25, 2009 And so here I am today. It’s been an interesting path that has lead me to Midway. Although born in Massachusetts, I grew up in Ventura, California. After getting involved with LBJ Enterprises (LBJ stands for “Little Bird Jobs”) when I was still in my teens, I moved to Arcata, California, and attended Humboldt State University. Living in a small community in the redwoods was a great experience…..I got to attend a very progressive school, befriend some amazing people, do a lot of bird work and play in a few punk rock bands to boot. After my stay behind The Redwood Curtain, I relocated to San Francisco to “settle down” for a while, but it did not take me long to figure out that’s not really what I wanted to do. The food, culture, music and people were great, but working in a corporate atmosphere and being surrounded by concrete much of the time got to be too much for me to take. So I quit my job as a wildlife biologist for an environmental consulting firm and moved out of my apartment in San Francisco. I am slated to be here until June, and I look forward to making more friends, meeting more people, watching the various seabird chicks grow up and hopefully find a few vagrant birds as well. Northwest Hawaiian Island Volunteer – March 11, 2009 The albatross monitoring work in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands would not be possible without the hard work of the many volunteers who assist on the project. This dedicated group of folks make many sacrifices to be here, including time away from friends and family with little or no pay. One of my favorite aspects of this job is getting to know the volunteers, and many have become good friends. Our volunteers come from all walks of life and they each bring a unique set of skills that help the project flourish. Occasionally we have a volunteer that enjoys the experience so much, they decide to volunteer a second time. Well, I'm happy to report, that one of my favorite volunteers from last season, Gary Nielsen, has come back again. Cheers Volunteering Gary Nielsen If you are interested in volunteering on this project or others like it in Hawaii, check out the federal government volunteer website. Duke University Students study on Midway - March 3, 2009 A Jack-of-all-Trades (1/28/09)

The albatross and most of the other 125 native birds that call Midway home for at least part of the year seem to be pretty happy here. They owe their happiness to all of the folks that dedicate their lives to protect, preserve, and enhance the biodiversity of Midway National Wildlife Refuge. These people include the staff of the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) that manage the refuge, as well as Chugach Alaska Corporation employees who are contracted by FWS to run operate the infrastructure on the Atoll. The 60 residents on Sand Island do an amazing job to keep the wildlife happy.

This morning we visited the FWS office to hear from John Klavitter, the wildlife biologist aka Jack-of-all-trades on Midway. John explained many of the conservation and management challenges that he faces in trying to enhance the habitat and biodiversity on Midway, and we learned that John is a true decathlete when it comes to solving the problems that arise. Not only does John do hard-core wildlife biology research as he was trained to do, but he also puts on many different hats including: construction worker, engineer, hunter (for nasty invasive species only), gardener, and even heavy machinery operator (which he highly recommends trying by the way). I really don’t know how he does it all, but he has greatly contributed to conservation on Midway since arriving here 7 years ago. One of the most exciting conservation success stories in which John played a vital role was the re-establishment of the highly endangered Laysan Duck on Midway. Laysan Ducks originally inhabited all Hawaiian Islands, but were restricted to Laysan Island in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands chain by 1900 because of humans and disease. Rabbits were introduced to Laysan Island as a protein source for villagers that lived there, and they ended up multiplying (like rabbits) and eating all of the native vegetation, thereby destroying Laysan Duck prime habitat.

Invasive species such as the Golden Crownbeard [a type of sunflower] can pose many problems for the birds on Midway. Of 267 total plant species on Midway, only 15 are native. The FWS therefore dedicates a lot of time and effort to killing and removing as many of these invasives as possible. Currently, only one land mammal (which is non-native) exists on Midway, the House Mouse (Mus musculus). But it wasn’t always that way! The eradication of the Black Rat (Rattus rattus) from Midway by the Navy in 1997 was, according to John, the single greatest conservation achievement on the atoll. In the 1940s, the Black rats were introduced accidentally to Midway as stowaways on cargo ships. They caused havoc as soon as they arrived, eating chicks, eggs, and even adult birds.

By 1945, they also caused the extinction of the Laysan Rail (Porzana palmeri), a flightless bird endemic to Laysan Island that also was established on Midway. The Navy therefore decided to fund an eradication program in 1994, using Japanese basket traps and bait stations, placed 100 feet apart all over the islands. It took $1 million and 3 years to get rid of the rats on Eastern, Spit, and Sand Islands, but it was worth it. We wouldn’t have the incredible numbers of seabirds nesting on Midway that we do today if it weren’t for the Navy’s rat eradication program. Luckily, the House Mouse isn’t quite as devastating as the Black rat was, but it does eat many of the native vegetation seeds, making FWS’s job of re-establishing native vegetation even harder.

Albatross chicks are truly amazing! When they hatch, they are covered in down feathers, they have their eyes open and most are able to lift their head up. Birds that have just hatched, even ones that are still wet from being inside the egg, are ready to eat right away. Newly hatched chicks are hungry, and they begin begging for food almost immediately.

Once the chick hatches, one adult will stay with it constantly, keeping it warm and dry, for up to three weeks. After that, the chick may be left alone for short periods as both adult go to the ocean to gather food. Eventually the adults will stop attending the nest altogether and will only return to it to feed the chick. The chick may wander away from the nest site, and subsequently get into all sorts of trouble (more on that in a later post), but they always go back to the nest when it’s time to get a meal!

Meet albatross biologist Marc Romano. His interview is located on our podcast site -- February 19, 2009

There are more than 800,000 Laysan albatross breeding at Midway Atoll NWR this year. When you look out across any open space you see literally a sea of birds. While individual birds may have minor, subtle differences in their appearance, to the untrained eye one Laysan albatross sitting on its nests looks pretty much identical to its neighbor.

Although my work at Midway Atoll NWR focuses on Laysan and black- Footed albatrosses, there is a third species of albatross that occurs in the North Pacific, the rare short-tailed albatross. Physically, they are the largest of the North Pacific albatrosses but they have the smallest population of the three. It is hard to imagine that this critically endangered species (estimated today at no more than 500 breeding pairs) is believed to have once been the most numerous albatross in the world. Nearly five decades of hunting for their feathers caused the short-tailed albatross population to decline so far that at one time scientists believed the species to be extinct. But in 1952, nearly twenty years since a short-tailed albatross had been observed, ten adults were sighted on the Japanese Island of Torishima.

Although Midway is not believed to have been an historical short- tailed albatross colony there are many records of individual birds visiting the atoll. The staff at Midway Atoll NWR, including Wildlife Biologist John Klavitter, have placed life-like plastic decoys of short-tailed albatrosses on Eastern Island at Midway to lure in individual birds. There are currently three short-tailed albatrosses that regularly visit Midway Atoll, including one adult of breeding age that we think is a male, and two juvenile birds that we are unsure of their gender. Unlike some birds that have very different plumage for males and females, albatross plumage differs with age but not with sex.

Last year one of the juveniles was seen courting with the adult bird and just a few weeks ago I saw them together again. They were preening each other and the adult was sitting on a nest bowl (although there was no egg in the nest). We are hopeful that these birds will begin breeding together some time in the future and that ultimately a new colony of short-tailed albatrosses will be formed in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Learn more about efforts to conserve short-tailed albatross in Japan by reading this Audubon Article by USFWS Wildlife Biologist Greg Balogh.

Time To Band the Birds - January 18, 2009 Bits and Pieces - January 14, 2009

"When we attain a new understanding of something in the field of

science, the thoughtful scientist is filled with wonder and a degree

of reverence for what we only partially understand." Cheers,

Welcome To Midway - January 7, 2009

Videos 2 juvenile blackfooted albatross bonding by practicing courtship dances on Sand Island, Midway Atoll NWR 2 juvenile laysan albatross bonding practicing courtship dances on Sand Island, Midway Atoll NWR Background Story "Living Poetry upon the Ocean” “I remember the first albatross I ever saw. It was during a prolonged gale, in waters hard upon the Antarctic seas... I saw a regal, feathery thing of unspotted whiteness, and with a hooked, Roman bill sublime. At intervals, it arched forth its vast archangel wings... Long I gazed at that prodigy of plumage. I cannot tell, can only hint, the things that darted through me then. But at last I awoke; and turning, asked a sailor what bird was this. A goney, he replied.” -Herman Melville from Moby Dick

The core of their breeding range is the collection of small islands and atolls of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. More than 96 percent of the world’s black-footed albatrosses and 98 percent of the world’s Laysan albatrosses breed on these islands, most of which are under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Populations of both black-footed and Laysan albatross have increased significantly since the cessation of feather hunting in the early 1900’s. However, globally the black-footed albatross is listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Laysan albatross is listed as vulnerable. These listings were based on predicted population declines from expected mortalities associated with longline commercial fishing. Other current and potential threats to these species include non-native, invasive predators at the breeding colonies, disease, contaminants and sea-level rise related to global climate change. In the United States, a petition to list black-footed albatrosses under the Endangered Species Act was submitted by Earth Justice in 2004 and is currently under review. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is moving toward the goal of maintaining or increasing black-footed and Laysan albatross populations by working with partners to quantify and address potential threats to these species. To guide this work the Service created a comprehensive Conservation Action Plan (Action Plan) and launched an innovative long-term monitoring program to track albatross populations at their breeding colonies.

The Action Plan groups conservation activities into six main categories that encompass most of the current conservation challenges: 1) Albatross Population Monitoring and Management, 2) Fisheries Bycatch Mitigation and Monitoring, 3) Habitat Restoration and Invasive Species Control, 4) Contaminant and Disease Monitoring and Abatement, 5) At-sea Habitat Utilization, and 6) Education and Outreach. The specific action items include both information development (to enable effective decision making) and direct management actions. Many of the highest priority actions identified in the plan address the issues of mitigation and monitoring of the incidental take of albatrosses in commercial fishing operations (fishery bycatch). Albatrosses spend much of their lives feeding at sea, and their foraging distribution often overlaps with commercial fishing operations. According to the IUCN, incidental fishery bycatch has been the most significant source of mortality for black-footed and many other albatross species. “More than a hundred thousand albatrosses [worldwide] drown in fishing gear every year,” said Dr. Beth Flint, a Wildlife Biologist with the Service’s Pacific Remote Islands Refuge Complex. “They are the most threatened family of birds in the world today,” she added. Biologists are working directly with fishers and industry groups on mitigation measures to reduce the bycatch of albatrosses. Methods such as adding weight to longline fishing gear to quickly sink baited-hooks, or setting fishing gear from the side of the boat instead of from the back are very effective in reducing bycatch. Some other successful measures include dyeing bait dark blue, deploying streamer lines to scare birds away from gear, and setting fishing gear at night. Hawaiian fleets have reduced seabird deaths by 97 percent by employing these techniques. But they aren’t the only fishing fleets on the open seas. In order to truly understand the full range of threats to albatrosses and assess the effectiveness of conservation actions, Service Wildlife Biologists Maura Naughton and Marc Romano with the Pacific Region, Office of Migratory Birds and Habitat Programs, have been working with partners to develop a standardized set of monitoring protocols. These protocols are the foundation of a demographic monitoring program that is being designed with the collaboration of scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland. The monitoring objective is to estimate a variety of key demographic parameters, such as adult survival, reproductive success and proportion of adults breeding each year. This is a challenging task given that Laysan and black-footed albatrosses are known to live to over 40 years of age. The information gained from this new monitoring program will allow the Service to track the health of black-footed and Laysan albatross populations over decades. This state-of-the-art monitoring effort is currently taking place on National Wildlife Refuge lands at the main albatross breeding colonies in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

A recurring theme in the development of the Action Plan is the integration of education and outreach. A public more aware of the unique nature of albatrosses and their conservation needs serves to generate support for conservation action. The breeding colonies on the main Hawaiian Islands have the potential to serve as demonstration sites where the public can view albatrosses first hand in their natural habitats. Webcams and other interpretive tools are being considered to bring the remote colonies of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands into homes and classrooms, spawning a conservation attitude toward albatrosses and other Pacific seabird species. This is an exciting time to spread the story of the albatross because emerging technology and innovative scientific research is providing a new window into their fascinating and unique life history. At the same time, the Service is working in diverse ways to ensure the future of this “living poetry upon the ocean…” which is how author Carl Safina so aptly described these magnificent birds. To learn more about the global conservation of this magnificent sea bird visit the Agreement for the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels Story written by: |

I’ve been here for exactly a month now, and am so glad I was lucky enough to make the long migration out to Midway Atoll. I first heard about Midway as a kid…..The Battle Of Midway, after all, was one of the most important events of America’s history. Then, years later, after I had become engrossed in birds, I heard of Midway mentioned in a different light……”amazing birdlife”……”America’s Galapagos”….and things of that nature. The more I educated myself about Midway and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the more I became determined to get myself here. So over the winter I applied for and was offered volunteer positions to both Tern Island and Midway, and after some deep thinking on the subject, I opted to come to Midway. Midway does have phones, a bar, and Short-tailed Albatross, after all.

I’ve been here for exactly a month now, and am so glad I was lucky enough to make the long migration out to Midway Atoll. I first heard about Midway as a kid…..The Battle Of Midway, after all, was one of the most important events of America’s history. Then, years later, after I had become engrossed in birds, I heard of Midway mentioned in a different light……”amazing birdlife”……”America’s Galapagos”….and things of that nature. The more I educated myself about Midway and the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the more I became determined to get myself here. So over the winter I applied for and was offered volunteer positions to both Tern Island and Midway, and after some deep thinking on the subject, I opted to come to Midway. Midway does have phones, a bar, and Short-tailed Albatross, after all. I first came to the Northwest Islands in June of 2000 on a “NOAA Teacher at Sea Program.” I spent 30 days on the Townsend Cromwell as part of a lobster assessment cruise and we stopped at Tern Island for several hours. I was hooked! I had seen a handful of Black-footed Albatross on Pelagic Trips but to see several thousand chicks and adults in one place was something special.

I first came to the Northwest Islands in June of 2000 on a “NOAA Teacher at Sea Program.” I spent 30 days on the Townsend Cromwell as part of a lobster assessment cruise and we stopped at Tern Island for several hours. I was hooked! I had seen a handful of Black-footed Albatross on Pelagic Trips but to see several thousand chicks and adults in one place was something special.  Day 8 on Midway did not disappoint. The sky-moos, bill-claps, and eh-eh bows from the thousands of albatross outside my Charlie Barracks Hotel window were just as loud as they’ve been everyday for the past week. Only, this time, I almost didn’t notice the racket when I awoke at 7 am. I guess after only a week at Midway, hearing and seeing the albatross clatter seems almost normal. I have to keep reminding myself that when I go back home in 2 days, I’m not going to be greeted by the wonderful sounds of the Laysan mating dance. But, as I stumble down the path to the Clipper House for breakfast, I still cannot keep myself from stopping every 5 minutes to watch a parent caress its chick, a pair dancing away, or a happy mother smiling on her nest waiting for her precious egg to hatch. OK, I admit it. Like everyone else, I’ve fallen in love with albatross.

Day 8 on Midway did not disappoint. The sky-moos, bill-claps, and eh-eh bows from the thousands of albatross outside my Charlie Barracks Hotel window were just as loud as they’ve been everyday for the past week. Only, this time, I almost didn’t notice the racket when I awoke at 7 am. I guess after only a week at Midway, hearing and seeing the albatross clatter seems almost normal. I have to keep reminding myself that when I go back home in 2 days, I’m not going to be greeted by the wonderful sounds of the Laysan mating dance. But, as I stumble down the path to the Clipper House for breakfast, I still cannot keep myself from stopping every 5 minutes to watch a parent caress its chick, a pair dancing away, or a happy mother smiling on her nest waiting for her precious egg to hatch. OK, I admit it. Like everyone else, I’ve fallen in love with albatross.

By 1911, only 11 ducks were left on the island with only a single breeding female! The rabbits were then eradicated from Laysan and from that one breeding female, the population grew to 600 by 1993. Later, a drought on the island caused a parasite outbreak, which once again reduced the population to only 100, so a team of biologists including John decided to establish a second population on Midway in 2005. John led the charge to create freshwater seeps for the ducks on Sand and Eastern Island and ever since then, the population’s been thriving!

By 1911, only 11 ducks were left on the island with only a single breeding female! The rabbits were then eradicated from Laysan and from that one breeding female, the population grew to 600 by 1993. Later, a drought on the island caused a parasite outbreak, which once again reduced the population to only 100, so a team of biologists including John decided to establish a second population on Midway in 2005. John led the charge to create freshwater seeps for the ducks on Sand and Eastern Island and ever since then, the population’s been thriving!

Break out the cigars and make sure you have a lot of them to share. We have many proud parents here at Midway because more than 400,000 albatross eggs have begun to hatch and little albatrosses are everywhere. The first black-footed albatross chicks hatched in the middle of January and our first Laysan albatross chicks hatched about a week or so later.

Break out the cigars and make sure you have a lot of them to share. We have many proud parents here at Midway because more than 400,000 albatross eggs have begun to hatch and little albatrosses are everywhere. The first black-footed albatross chicks hatched in the middle of January and our first Laysan albatross chicks hatched about a week or so later.  Laysan and black-footed albatross females only lay one egg per year. So if for some reason that egg is broken or lost they are not able to lay a second one to replace it. Both the male and female parents share in the duties of incubating the egg, although the male will usually spend more time on the egg than the female. After about 65 days of incubation the egg will hatch, and then the real work begins for the adults. While incubating the egg, the daily routine of the parent birds is pretty simple; as one bird incubates the egg, keeping it covered, warm and dry, the other bird is typically out to sea foraging for food. The parents usually time it so that one bird is coming in from the ocean, and thus full of food, right when the chick is hatching. This ensures that the chick has food immediately.

Laysan and black-footed albatross females only lay one egg per year. So if for some reason that egg is broken or lost they are not able to lay a second one to replace it. Both the male and female parents share in the duties of incubating the egg, although the male will usually spend more time on the egg than the female. After about 65 days of incubation the egg will hatch, and then the real work begins for the adults. While incubating the egg, the daily routine of the parent birds is pretty simple; as one bird incubates the egg, keeping it covered, warm and dry, the other bird is typically out to sea foraging for food. The parents usually time it so that one bird is coming in from the ocean, and thus full of food, right when the chick is hatching. This ensures that the chick has food immediately.  It is exactly this bird that I have been searching for over the last few weeks and I am extremely excited to have finally found her. My friends and colleagues Dr. Beth Flint and Junichi Sugishita share my excitement, and are eagerly snapping photos of this bird with the red color leg band with the code number of Z333.

It is exactly this bird that I have been searching for over the last few weeks and I am extremely excited to have finally found her. My friends and colleagues Dr. Beth Flint and Junichi Sugishita share my excitement, and are eagerly snapping photos of this bird with the red color leg band with the code number of Z333. From this group the worldwide population of short-tailed albatrosses has slowly, but steadily increased. There are now two colonies that support breeding populations of short-tails and individual birds have been observed prospecting for sites at other locations, including Midway.

From this group the worldwide population of short-tailed albatrosses has slowly, but steadily increased. There are now two colonies that support breeding populations of short-tails and individual birds have been observed prospecting for sites at other locations, including Midway.

The project that I am in charge of out here on Midway Atoll is a

long-term demographic monitoring study of Laysan and black-footed

albatross. Albatross of all species can live for a very long time,

and one of the most important demographic parameters that we want

to monitor is the annual survival of adults. To do this we are conducting

a mark-recapture study. The basic idea of a mark-recapture study

is pretty simple; mark a sample of individuals in a way that you

can distinguish them apart, and then take a fresh sample of individuals

and compare the number of marked to unmarked. If you do this in a

systematic way over time, you can determine how long individuals

are living for and what percentage of the individuals survive from

year to year.

The project that I am in charge of out here on Midway Atoll is a

long-term demographic monitoring study of Laysan and black-footed

albatross. Albatross of all species can live for a very long time,

and one of the most important demographic parameters that we want

to monitor is the annual survival of adults. To do this we are conducting

a mark-recapture study. The basic idea of a mark-recapture study

is pretty simple; mark a sample of individuals in a way that you

can distinguish them apart, and then take a fresh sample of individuals

and compare the number of marked to unmarked. If you do this in a

systematic way over time, you can determine how long individuals

are living for and what percentage of the individuals survive from

year to year. My work out here on Midway requires a lot of direct contact with the birds. We are putting bands on individual birds so that we can track

them over time to better understand factors that effect adult

survival and breeding success. To get the bands on the birds we have

to reach under them while they sit on their nest, incubating their

eggs. We prefer not to pick them up or restrain them to put the bands

on because it can be stressful for the birds and the humans. Although

most of the birds are pretty mellow, some birds take offense with us

reaching under them and they lash out with their bill. The albatross

bill is extremely well adapted for snatching up small squid (their

primary prey item) off the water. However, it is also incredibly well

suited for grabbing and tearing fingers, backs of hands, shins,

ankles and any soft body part that gets within snapping radius. It is

not hard to tell who on Midway is working on the albatross, all you

have to do is check their wrists and hands for bits and pieces of

missing skin.

My work out here on Midway requires a lot of direct contact with the birds. We are putting bands on individual birds so that we can track

them over time to better understand factors that effect adult

survival and breeding success. To get the bands on the birds we have

to reach under them while they sit on their nest, incubating their

eggs. We prefer not to pick them up or restrain them to put the bands

on because it can be stressful for the birds and the humans. Although

most of the birds are pretty mellow, some birds take offense with us

reaching under them and they lash out with their bill. The albatross

bill is extremely well adapted for snatching up small squid (their

primary prey item) off the water. However, it is also incredibly well

suited for grabbing and tearing fingers, backs of hands, shins,

ankles and any soft body part that gets within snapping radius. It is

not hard to tell who on Midway is working on the albatross, all you

have to do is check their wrists and hands for bits and pieces of

missing skin. Arriving to the airport at Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge is unlike any other travel experience in the world. First off, all flights during the albatross breeding season land at night in order to reduce the chances of a collision with a flying bird. Now arriving at night to an exotic destination is not too out of the ordinary, except that the darkness at Midway obscures the presence of over 1 million breeding seabirds! Despite the darkness though it doesn't take long to figure out that the 60 or so human residents of the island are in the vast minority here. Alabtrosses are quite literally everywhere at Midway, and any surface that is not concrete is covered in nesting birds!

Arriving to the airport at Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge is unlike any other travel experience in the world. First off, all flights during the albatross breeding season land at night in order to reduce the chances of a collision with a flying bird. Now arriving at night to an exotic destination is not too out of the ordinary, except that the darkness at Midway obscures the presence of over 1 million breeding seabirds! Despite the darkness though it doesn't take long to figure out that the 60 or so human residents of the island are in the vast minority here. Alabtrosses are quite literally everywhere at Midway, and any surface that is not concrete is covered in nesting birds!  The “gooney bird,” or albatross, is a bird of legend and extremes. Long viewed as a symbol of good omen, this wondrous group of birds boasts the species with the longest wingspan at over 11 feet. Soaring on these “vast archangel wings” the albatross is one of the greatest long distance wanderers in the world. A breeding albatross can fly more than 10,000 miles to deliver a single meal to its chick and a fledgling wandering albatross will fly over 110,000 miles in its first year alone.

The “gooney bird,” or albatross, is a bird of legend and extremes. Long viewed as a symbol of good omen, this wondrous group of birds boasts the species with the longest wingspan at over 11 feet. Soaring on these “vast archangel wings” the albatross is one of the greatest long distance wanderers in the world. A breeding albatross can fly more than 10,000 miles to deliver a single meal to its chick and a fledgling wandering albatross will fly over 110,000 miles in its first year alone.  The breeding populations and ranges of both species were greatly reduced during the 1800s and early 1900s when hunters extirpated birds from most of the colonies in the Western Pacific to provide feathers for the millinery trade. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt sent marines to guard Midway Atoll to protect the birds against hunters, and in 1909 he declared the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands a bird reservation. This area later became the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge and today is included in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, one of the largest marine protected areas in the world.

The breeding populations and ranges of both species were greatly reduced during the 1800s and early 1900s when hunters extirpated birds from most of the colonies in the Western Pacific to provide feathers for the millinery trade. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt sent marines to guard Midway Atoll to protect the birds against hunters, and in 1909 he declared the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands a bird reservation. This area later became the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge and today is included in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, one of the largest marine protected areas in the world. The Action Plan was initiated by the Fish and Wildlife Service, but it is truly the product of a diverse group of agencies, organizations, and individuals with a responsibility or interest in albatross conservation. The Action Plan is intended to provide a framework for partnership-based conservation and management. The core of the document is a list of specific action items that, when implemented, will reduce threats to black-footed and Laysan albatrosses and prevent or stem population declines.

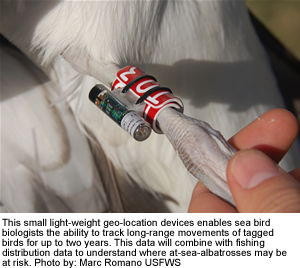

The Action Plan was initiated by the Fish and Wildlife Service, but it is truly the product of a diverse group of agencies, organizations, and individuals with a responsibility or interest in albatross conservation. The Action Plan is intended to provide a framework for partnership-based conservation and management. The core of the document is a list of specific action items that, when implemented, will reduce threats to black-footed and Laysan albatrosses and prevent or stem population declines.  Several other Action Plan priorities have similarly moved quickly into implementation. In one example, Naughton and Romano are teaming up with Dr. Scott Shaffer of the University of California, Santa Cruz to track the long-range movements of albatrosses at sea using cutting edge geo-location technology. These small, lightweight devices enable the team to track the daily movements of tagged birds for over a two year period. Ultimately, this data will be combined with information on fishing distribution and intensity to determine areas where at-sea albatrosses may be at risk.

Several other Action Plan priorities have similarly moved quickly into implementation. In one example, Naughton and Romano are teaming up with Dr. Scott Shaffer of the University of California, Santa Cruz to track the long-range movements of albatrosses at sea using cutting edge geo-location technology. These small, lightweight devices enable the team to track the daily movements of tagged birds for over a two year period. Ultimately, this data will be combined with information on fishing distribution and intensity to determine areas where at-sea albatrosses may be at risk.