Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

Status | Taxonomy | Species Description | Habitat | Distribution |

Population Trends | Threats | Conservation Efforts | Regulatory Overview |

Key Documents | More Info

Status

ESA Endangered - 2 ESUs

ESA Threatened - 7 ESUs

ESA Species of Concern - 1 ESU

More information on all 17 Chinook salmon ESUs is available on NMFS Northwest Regional Office website.

Taxonomy

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Osteichthyes

Order: Salmoniformes

Family: Salmonidae

Genus: Oncorhynchus

Species: tshawytscha

Species Description

Chinook salmon are easily the largest of any salmon, with adults often exceeding 40 pounds (18 kg); individuals over 120 pounds (54 kg) have been reported. Chinook mature at about 36 inches and 30 pounds.

Chinook salmon are very similar to coho salmon in appearance while at sea (blue-green back with silver flanks), except for their large size, small black spots on both lobes of the tail, and black pigment along the base of the teeth.

Adults migrate from a marine environment into the freshwater streams and rivers of their birth in order to mate (called anadromy). They spawn only once and then die (called semelparity).

They feed on terrestrial and aquatic insects, amphipods, and other crustaceans while young, and primarily on other fishes when older.

Populations exhibit considerable variability in size and age of maturation, and at least some portion of this variation is genetically determined. There is a relationship between small size and long distance of migration that may also reflect the earlier timing of river entry and the cessation of feeding for Chinook salmon stocks that migrate to the upper reaches of river systems. Body size, which is related to age, may be an important factor in migration and spawning bed, or redd, construction success.

Juvenile Chinook may spend from 3 months to 2 years in freshwater before migrating to estuarine areas as smolts and then into the ocean to feed and mature. Chinook salmon remain at sea for 1 to 6 years (more commonly 2 to 4 years), with the exception of a small proportion of yearling males (called jack salmon) which mature in freshwater or return after 2 or 3 months in salt water.

There are different seasonal (i.e., spring, summer, fall, or winter) "runs" in the migration of Chinook salmon from the ocean to freshwater, even within a single river system. These runs have been identified on the basis of when adult Chinook salmon enter freshwater to begin their spawning migration. However, distinct runs also differ in the degree of maturation at the time of river entry, the temperature and flow characteristics of their spawning site, and their actual time of spawning. Freshwater entry and spawning timing are believed to be related to local temperature and water flow regimes.

Adult female Chinook will prepare a redd (or nest) in a stream area with suitable gravel type composition, water depth and velocity. The adult female Chinook may deposit eggs in 4 to 5 "nesting pockets" within a single redd. Spawning sites have larger gravel and more water flow up through the gravel than the sites used by other Pacific salmon. After laying eggs in a redd, adult Chinook will guard the redd from just a few days to nearly a month before dying.

Chinook salmon eggs will hatch, depending upon water temperatures, 3 to 5 months after deposition. Eggs are deposited at a time to ensure that young salmon fry emerge during the following spring when the river or estuary productivity is sufficient for juvenile survival and growth.

As the time for migration to the sea approaches, juveniles lose their parr marks, the pattern of vertical bars and spots useful for camouflage. They then gain the dark back and light belly coloration used by fish living in open water. Chinook salmon seek deeper water, avoid light, and their gills and kidneys begin to change so that they can process salt water.

Two distinct types or races among Chinook salmon have evolved.

One race, described as a "stream-type" Chinook, is found most commonly in headwater streams of large river systems. Stream-type Chinook salmon have a longer freshwater residency, and perform extensive offshore migrations in the central North Pacific before returning to their birth, or natal, streams in the spring or summer months. Stream-type juveniles are much more dependent on freshwater stream ecosystems because of their extended residence in these areas. A stream-type life history may be adapted to areas that are more consistently productive and less susceptible to dramatic changes in water flow. At the time of saltwater entry, stream-type (yearling) smolts are much larger, averaging 3 to 5.25 inches (73-134 mm) depending on the river system, than their ocean-type (subyearling) counterparts, and are therefore able to move offshore relatively quickly.

The second race, called the "ocean-type" Chinook, is commonly found in coastal streams in North America. Ocean-type Chinook typically migrate to sea within the first three months of life, but they may spend up to a year in freshwater prior to emigration to the sea. They also spend their ocean life in coastal waters. Ocean-type Chinook salmon return to their natal streams or rivers as spring, winter, fall, summer, and late-fall runs, but summer and fall runs predominate. Ocean-type Chinook salmon tend to use estuaries and coastal areas more extensively than other pacific salmonids for juvenile rearing. The evolution of the ocean-type life history strategy may have been a response to the limited carrying capacity of smaller stream systems and unproductive watersheds, or a means of avoiding the impact of seasonal floods. Ocean-type Chinook salmon tend to migrate along the coast. Populations of Chinook salmon south of the Columbia River drainage appear to consist predominantly of ocean-type fish.

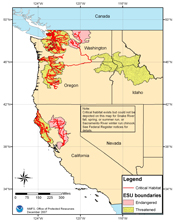

Chinook Salmon Critical Habitat (click for larger view PDF) |

|

Chinook Salmon Range Map (click for larger view PDF) |

Habitat

Juvenile Chinook may spend from 3 months to 2 years in freshwater before migrating to estuarine areas as smolts and then into the ocean to feed and mature. They prefer streams that are deeper and larger than those used by other Pacific salmon species.

Critical habitat has been designated for the 9 ESA-listed Chinook salmon ESUs.

Distribution

In the U.S., Chinook salmon are found from the Bering Strait area off Alaska south to Southern California. Historically, they ranged as far south as the Ventura River, California. Maps of the 17 ESUs of Chinook salmon are available on the NMFS Northwest Regional Office website.

Chinook salmon also occur along the coast of Siberia and south to Hokkaido Island, Japan.

Population Trends

In recent years, some populations have shown encouraging increases in population size. Population trends for specific ESUs can be found in the 2005 status review report for Pacific salmon and steelhead [pdf] [6.3 MB].

Threats

Salmonid species on the west coast of the United States have experienced dramatic declines in abundance during the past several decades as a result of human-induced and natural factors. For more information, please visit our Pacific salmonids threats page.

Conservation Efforts

A variety of conservation efforts have been undertaken with some of the most common initiatives including captive-rearing in hatcheries, removal and modification of dams that obstruct salmon migration, restoration of degraded habitat, acquisition of key habitat, and improved water quality and instream flow.

The Pacific Coast Salmon Recovery Fund (PCSRF) was established by Congress in 2000 to support the restoration of salmon species. The fund is overseen by NMFS and carried out by state and tribal governments. The 2006 PCSRF report summarizes their work in detail.

No Pacific salmon have been evaluated for IUCN Redlist ![]() conservation status.

conservation status.

Regulatory Overview

In 1985, NMFS received a petition to list under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) the winter run of Chinook salmon in the Sacramento River. In 1990, they were listed as Threatened. NMFS received another petition to list this population as Endangered and this occurred in 1994.

In 1990, NMFS received a petition to list Snake River Chinook; two ESUs from this river were listed.

After these listings and receiving other petitions to list Pacific salmonids, the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Southwest Fisheries Science Center launched a systematic review of all West Coast salmon runs. A detailed listing history of all Chinook salmon ESUs is available on the NMFS Northwest Regional Office website.

Critical habitat has been designated for the 9 ESA-listed Chinook salmon ESUs.

Key Documents

(All documents are in PDF format.)

| Title | Federal Register | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Recovery Plan for Upper Columbia Spring-run Chinook | 72 FR 57303 | 10/09/2007 |

| Recovery Plan for Puget Sound Chinook | 72 FR 2493 | 01/19/2007 |

| Status Review Update of All ESA-Listed ESUs | n/a | 06/2005 |

| Final 4(d) Protective Regulations for Threatened Salmonid ESUs | 65 FR 42422 | 07/10/2000 |

| ESA Listing Rules, Critical Habitat Designations, and other Chinook Federal Register Notices | various | various |