|

Press Release 07-122

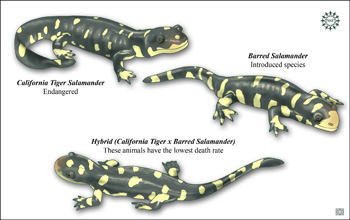

Interbreeding Between Invasive and Native Salamander Species Creates Hardy Hybrids Likely to Replace Parental Populations

Discovery of salamander hybrids has important implications for evolution and conservation

September 18, 2007

Interbreeding between the California Tiger Salamander--which is a native, endangered species--and the invasive Barred Tiger Salamander has produced a swarm of hybrid salamanders that is more likely to survive than either parent species, according to a new study. Found in Salinas, California, the swarm of hybridized salamanders may comprise the first population of sustainable hybrids created by an interbreeding involving an endangered species, and is among the first known sustainable populations of a hybrid animal. The conservation issues raised by the discovery of the salamander hybrid may "serve as a model" for those issues to be raised by future discoveries of hybrids created by interbreeding between an endangered species and an invasive species, says Brad Shaffer of the University of California, who is a co-author of the study. Because of advances in genetic analyses and because of increases in invasive species, Shaffer expects increasing numbers of hybrids to be discovered in the future. The study of the hybridization of the California Tiger Salamander and the invasive Barred Tiger Salamander, which was introduced to the study area about 50 years ago as fishing bait, is described in the September 17 issue of The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This research was partially funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). When two plant species or two animal species are able to mate, they create hybrid offspring. But hybridization has usually been considered "an evolutionary dead end," says Benjamin Fitzpatrick of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who is the study's lead author. This is because "the mixture of genes from organisms that are distinct enough to be called separate species don't usually produce healthy, fit offspring" that can sustain themselves. In scientific terms, hybrids usually lack "fitness." (In the classic example of a horse mating with a donkey, the resulting mule is sterile and therefore less fit than both of its parents.) But Fitzpatrick and Shaffer say that the larvae of hybrids produced by interbreeding between California Tiger Salamanders and invasive Barred Tiger Salamanders are more likely to survive than larvae of either parent species. The researchers base this finding on their comparison of the genetic profiles of surviving salamander larvae with the genetic profiles of the initial pool of hatchlings in five wild populations. The California Tiger Salamander and the Barred Tiger Salamander evolved independently for millions of years and are about as genetically different from one another as are humans and chimpanzees. Therefore, the researchers say that their field studies of hybrid fitness show that hybridization can change evolutionary processes by conferring genetic advantages to hybrids. The researchers say that their results also indicate that some non-native salamander genes may eventually spread to all California Tiger salamanders. In a sense, the entire species would then have hybrid ancestry. "We always worry that invasive species will displace existing species," says Samuel Scheiner, an NSF Program Director. "But with hybridization, you lose an existing species not because it is driven to extinction by competition, but because its genes are mixed with those of another species. While we have known about the potential threat to endangered species posed by hybridization, this study represents one of the first demonstrations of this threat." The researchers do not yet know why the hybrids are thriving. According to Fitzpatrick, "the hybrids could be more resistant to disease, better able at escaping predators, or more efficient at gathering food than their parent species." But no matter why the salamanders are thriving, their success raises questions about whether hybridization is beneficial to native species. Some conservationists, for example, may consider hybridization that is favored by natural selection to be an acceptable human-mediated change because it strengthens the original species, says Shaffer. By contrast, other conservationists may consider hybrids to be genetically impure and regard them as threats to native species and as potential threats to competitor and prey species. But Shaffer adds that "to get rid of the fraction of genes coming from the invasive species, you would have to fight natural selection, which is difficult." As hybrids blur genetic lines, they also blur legal definitions. Would, for example, the hybrid salamanders qualify for the same protection under the Endangered Species Act as the endangered California Tiger Salamander? Fitzpatrick says that besides the salamander hybrids, he only knows of one other sustainable animal hybrid and three sustainable plant hybrids. But as more hybrids are created by the interbreeding of endangered and invasive species, the thorny scientific and conservation questions posed by hybrids will increase as well.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Lily Whiteman, National Science Foundation (703) 292-8310 lwhitema@nsf.gov

Jay Mayfield, University of Tennessee, Knoxville (865) 974-9409 jay.mayfield@tennessee.edu

Syvlia Wright, University of California, Davis 530-752-7704 swright@ucdavis.edu

Program Contacts

Sam Scheiner, National Science Foundation (703) 292-7175 scheine@nsf.gov

Principal Investigators

Benjamin Fitzpatrick, University of Tennessee, Knoxville (865)-974-9734 benfitz@utk.edu

Co-Investigators

H. Bradley Schaffer, University of California, Davis (530) 752-2939 hbshaffer@ucdavis.edu

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering. In fiscal year (FY) 2009, its budget is $9.5 billion, which includes $3.0 billion provided through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to over 1,900 universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives about 44,400 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly.

Get News Updates by Email Get News Updates by Email

Useful NSF Web Sites:

NSF Home Page: http://www.nsf.gov

NSF News: http://www.nsf.gov/news/

For the News Media: http://www.nsf.gov/news/newsroom.jsp

Science and Engineering Statistics: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards Searches: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

|