|

Press Release 05-024

New Clues Add 40,000 Years to Age of Human Species

Follow-up to 1967 expedition links climatic and radiometric dating to controversial Ethiopian bones

February 16, 2005

Nearly 40 years after an historic anthropology expedition to Ethiopia's Lake Turkana basin, researchers have uncovered evidence suggesting human bones found at that time are roughly 195,000 years old. The researchers believe the findings may bolster the “Out-of-Africa” hypothesis that suggests we all trace to an ancient line that first evolved in Africa and then displaced other hominids as recently as 50,000 years ago.

Ian McDougall of Australian National University (ANU), Frank Brown of the University of Utah and John Fleagle of Stony Brook University, report their findings in the Feb. 17 issue of the journal Nature.

The fossils, from near the town of Kibish, are far more ancient than researchers originally suspected and nearly 40,000 years older than skulls from Herto, Ethiopia, the previous record holders.

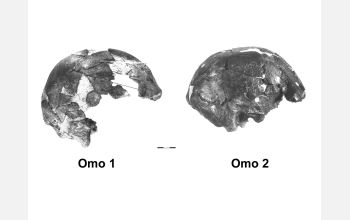

The Kibish hominids—dubbed Omo I and Omo II—were once entombed in sediments on opposite sides of the Omo River in southern Ethiopia. By applying modern radiometric dating techniques and a careful study of sediments and fossils, the researchers linked the Omo hominids, true Homo sapiens, to a single period in time.

“Some have considered Omo I to be more ‘modern’ in appearance,” says Mark Weiss, the NSF officer who oversaw this research. “It’s fascinating that we can now see that these two rather different individuals were living at the same time and in the same region,” he adds.

The researchers also discovered the fossil-rich strata can be linked to sapropels, sediment layers found in the eastern Mediterranean, which, along with ice cores, tree rings and annual lake deposits, are part of the geological record scientists study for indications of climate change. The team believes the Africa-Mediterranean correlation ties both regions to moister climates long ago, yielding another method to understand climate history in that part of the world.

“The correlation between the Kibish deposits and the Mediterranean sapropels not only helps us resolve an anthropological mystery, but it provides a whole new perspective on the history of the Turkana Basin, a setting that has provided so much important evidence regarding human evolution,” says Brown.

“However, while our research pushes back our time of origin," he adds, “most cultural aspects of humanity appear much later in the record—only 50,000 years ago—which would mean 150,000 years of Homo sapiens without harpoons, music, needles or even most tools. This is another mystery yet to be solved," he said.

When Richard Leakey, F. Clark Howell, Camile Arambourg and teams of Kenyan, American and French researchers first ventured to the Lake Turkana region in 1967, they searched for the earliest remains of pre-human ancestors. Modern humans were not a priority at the time, and when members of the Kenyan team found Omo I and Omo II, the specimens failed to create much of a stir.

Since that early expedition, supported by both the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Geographic Society, the age of the Omo hominids has become somewhat more controversial, and more critical, to understanding the dawn of Homo sapiens.

Since the 1980s, almost everyone agreed that our ancestors originated on the African continent, but they differed on when modern humans first evolved, how humans dispersed to populate the globe, and what happened when, or if, modern humans encountered other hominid species in Eurasia.

“For several decades, the Kibish fossils have been a key element in arguments for an ancient origin of modern humans in Africa, yet one for which the age and provenance of the fossils was repeatedly contested,” notes Fleagle.

At the request of their Ethiopian colleague Zelalem Assefa, now at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., the NSF-supported team of anthropologists, geologists and paleontologists revisited the site in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Initially, the team relied heavily on Brown, who accompanied the American contingent of the 1967 International Omo Research Expedition. Yet, there were flaws in the published map, and the team was unable to pinpoint the exact spots that had yielded the original fossils.

The researchers then came across an unusual resource: unused film footage taken by National Geographic photographers for a never-aired documentary on the original expedition. By matching features such as hills from the film to landmarks in the field, together with a hand drawn map from the late Paul Abell and photographs by Karl Butzer, both members of the 1967 expedition, the researchers were able to precisely locate the original fossil outcrops.

The scientists collected hundreds of new mammal fossils that helped differentiate layers of sediment and link the currently dry region to its moister climates of the past. But, precisely dating the outcrops required volcanic minerals with elements that undergo radioactive decay.

Brown and McDougall collected rocks containing volcanic debris, which McDougall dated to approximately 195,000 years old.

Forty years ago, radiometric dating methods were less accurate and suggested an age of roughly 130,000 years. No one was able to securely tie both sets of fossils to the same time period.

"Fortunately, small pumice fragments from two sediment layers were perfect for precise isotopic dating," says McDougall. “The pumice clasts are produced by explosive volcanic eruptions, and the rocks were probably carried to the Lake Turkana basin soon after, providing a time stamp for nearby sediments,” he adds. The results revealed how long ago the eruption occurred: roughly 196,000 years.

"This provided an unambiguous maximum age for the fossils,” says McDougall.

Further supporting the dates, the researchers linked sediments deposited by the Omo River to periodic, well-dated sapropels – layers of organic-rich sediments thousands of kilometers north in the Mediterranean that other researchers had already associated with specific, episodic climate changes.

In addition, the sediments show that each major layer deposited very rapidly, perhaps within a few thousand years or less. In the case of the Omo hominids, the researchers linked the isotopic ages to a brief period during which sediments entombed both sets of bones.

Together, the various lines of evidence seem to constrain the dates of the fossil human remains found at the Omo River to an age near 195,000 years ago, say the researchers, an age that agrees with estimates from genetic studies for the age of the last, common Homo sapiens ancestor, and reinforcing evidence that most of human history transpired in Africa.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the L. S. B. Leakey Foundation, the National Geographic Society and the Australian National University.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Joshua A. Chamot, NSF (703) 292-8070 jchamot@nsf.gov

Program Contacts

Mark L. Weiss, NSF (703) 292-7321 mweiss@nsf.gov

Co-Investigators

Ian McDougall, Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra +61 2 6125 4136 Ian.McDougall@anu.edu.au

John G. Fleagle, Department of Anatomical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook University, New York (631) 444-312 jfleagle@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

Frank Brown, Professor of geology and geophysics, dean of the College of Mines and Earth Sciences, University of Utah (801) 581-8767 fbrown@mines.utah.edu

Related Websites

Frank Brown homepage: http://www.mines.utah.edu/geo/

John Fleagle homepage: http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/ee/ee-fac2.html#fleagle

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering. In fiscal year (FY) 2009, its budget is $9.5 billion, which includes $3.0 billion provided through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to over 1,900 universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives about 44,400 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly.

Get News Updates by Email Get News Updates by Email

Useful NSF Web Sites:

NSF Home Page: http://www.nsf.gov

NSF News: http://www.nsf.gov/news/

For the News Media: http://www.nsf.gov/news/newsroom.jsp

Science and Engineering Statistics: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards Searches: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

|