|

Press Release 08-124

Outflow from World's Largest River --the Amazon--Powers Atlantic Ocean Carbon "Sink"

Microbes in tropical ocean waters lead to increased carbon uptake

July 21, 2008

View a video interview of biological oceanographer Ajit Subramaniam and marine scientist Doug Capone.

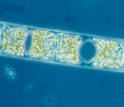

Nutrients from the Amazon River's outflow spread well beyond the continental shelf and drive carbon cycling in the tropical ocean, say scientists who conducted a multi-year study. They will publish their results this week online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The researchers discovered a significant and surprising drawdown of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the tropical ocean by microorganisms living in the Amazon River's outflow. The finding reveals the surprisingly large role of tropical oceans and major rivers in the oceans' total carbon uptake. "This work has led to an important discovery about the source of nitrogen that fuels the productivity of tropical ocean waters, especially those into which large rivers flow," said David Garrison, director of the National Science Foundation (NSF)'s biological oceanography program. NSF's Biocomplexity in the Environment program funded the research. The Amazon River is the largest river in the world by volume; it also has the largest drainage basin on the planet, accounting for some one fifth of Earth's total river flow. Because of its vast dimensions, it's sometimes called "the river sea." The Amazon River's outflow covers an area more than twice the size of the state of Texas for several months each year, said Ajit Subramaniam, a biological oceanographer at Columbia University and lead author of the PNAS paper. (Subramaniam is currently on leave from Columbia, now serving as a rotating program director at NSF.) The tropical North Atlantic had been considered a net emitter of carbon from the respiration of ocean life. A 2007 study estimated the tropical Atlantic Ocean's carbon contribution to the atmosphere at 30 million tons annually. The new study finds that the respiration is offset by phytoplankton, most of which belong to a group of organisms called diazotrophs. Diazotrophs take nitrogen and carbon from the air and use them to make organic solids that sink to the ocean floor. Diazotrophs "fix" nitrogen, enabling them to thrive in nutrient-poor waters. They also require small amounts of phosphorus and iron, which the Amazon River brings to ocean waters far offshore. The microscopic life forms responsible for this carbon drawdown change along the river outflow, said Subramaniam. "These organisms are regulated by the biogeochemistry of the river, and are sensitive to land-use alterations and climate change. Activities such as dam construction and changing agricultural practices will alter the magnitude of this drawdown." Other large tropical rivers of the world also may contribute to carbon capture, said Doug Capone, a marine scientist at the University of Southern California and co-author of the PNAS paper, adding that studies on such rivers are in progress. Polar seas are still responsible for most of the oceans' carbon uptake. But though carbon dioxide dissolves more easily in cooler waters, the warm oceans may be where a permanent carbon sink is more likely, said Capone. "The important places are probably not the high latitudes, but rather the low latitude areas where nitrogen fixation is a predominant process," Capone said. The other authors of the paper are researchers from the University of Georgia, Athens; San Francisco State University; the University of Liverpool; the University of Hawaii, Honolulu; Rutgers University; Georgia Institute of Technology; and the University of California, Los Angeles.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF (703) 292-7734 cdybas@nsf.gov

Kevin Krajick, Columbia University (845) 365-8607 kkrajick@ldeo.columbia.edu

Carl Marziali, University of Southern California (213) 740-4751 marziali@usc.edu

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering. In fiscal year (FY) 2009, its budget is $9.5 billion, which includes $3.0 billion provided through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to over 1,900 universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives about 44,400 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 11,500 new funding awards. NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly.

Get News Updates by Email Get News Updates by Email

Useful NSF Web Sites:

NSF Home Page: http://www.nsf.gov

NSF News: http://www.nsf.gov/news/

For the News Media: http://www.nsf.gov/news/newsroom.jsp

Science and Engineering Statistics: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/

Awards Searches: http://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/

|