Lymphedema After Cancer - How Serious Is It?

Many people who survive cancer will suffer from a serious side effect of treatment known as lymphedema, and they may not even know about it.

Many people who survive cancer will suffer from a serious side effect of treatment known as lymphedema, and they may not even know about it.

The lymphatic system comprises a very fine network of vessels and filtering nodes that circulate lymph (the fluid that bathes cells with nutrients and helps clear away waste and infection) throughout the body. Lymphedema results when part of this system is interrupted - when lymph nodes or vessels are removed or damaged, causing a "traffic jam" of lymph to build up.

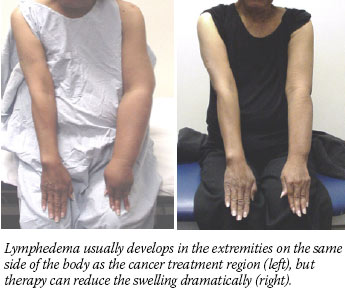

Patients often describe the resulting swelling in the distal limb or tissue on the side of the body where the damage occurred as feelings of heaviness, fatigue, and tightness. Over time, swelling can increase dramatically and be accompanied by sclerosis that makes it permanent.

|

As of 2006, 21 states require insurers to cover treatment for lymphedema after cancer. To find out the requirements for insurance coverage in your state, go to NCI's State Cancer Legislative Database Program.

Patients can also find more information about lymphedema, including therapists and support groups in their area, by contacting the National Lymphedema Network.

|

Estimates for lymphedema incidence after breast cancer treatment range from 6 to 30 percent. But because the definitions of lymphedema and its severity vary, because many patients have never heard about lymphedema and so never seek medical help, and because tracking lymphedema through medical records is not required, experts agree the incidence is probably higher.

Recent research supports that contention. In the largest prospective study of its kind, published last month in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 32 percent of women aged 45 years and younger treated for breast cancer had persistent swelling in the hand and/or arm 3 years after surgery. The incidence of episodic swelling was 54 percent.

"This doesn't just happen in a few women," says the study's lead investigator, Dr. Electra Paskett from Ohio State University's College of Public Health and Comprehensive Cancer Center. "It's a serious consequence of treatment in terms of magnitude." Dr. Paskett is also a breast cancer survivor who lives with lymphedema.

"When I was diagnosed with breast cancer 10 years ago, during radiation I developed swelling in my affected hand and index finger," she continues. "My radiation oncologist referred me to a physical therapist, and that's how I found out about lymphedema."

Dr. Paskett's subsequent research with breast cancer survivors showed that lymphedema can have a devastating impact on quality of life, and that communication between physicians and patients on the risks for and signs of lymphedema was sparse, when it happened at all.

Why one patient may develop lymphedema while another does not is still unclear. In general, the greater the number of lymph nodes removed, the higher the risk. The risk after axillary node dissection is much greater than after sentinel node biopsy. Radiation is another risk factor, as is obesity and infection after surgery.

Everyone agrees that there is a great need for patients and physicians to understand risks for and symptoms of lymphedema, and know that there are ways to treat it and manage it.

"It's about creating pathways for the lymph fluid to drain," says Dr. Tammy Mondry, a physical therapist in San Diego, CA, who is certified by the Lymphology Association of North America in lymphedema treatment. Most of Dr. Mondry's patients are breast cancer survivors, though a significant portion developed lymphedema after gynecological cancer, prostate cancer, or melanoma treatment.

Dr. Mondry performs manual lymph drainage to stimulate the pumping rate of the healthy lymph vessels throughout the body. This is one part of a four-part treatment called Complete Decongestive Therapy, which is performed 5 days a week for 2 to 4 weeks and includes compression bandaging with short stretch bandages that are worn 24 hours per day until the decrease in swelling plateaus. After that, the patient wears a compression garment daily for maintenance.

Dr. Mondry teaches people how to perform this massage on their own, as well as exercises and skin and nail care, which are especially important because the lymph that builds up in swollen limbs increases the risk for and severity of infections.

Dr. Paskett and other researchers are looking at ways to prevent lymphedema in women who receive a full axillary node dissection as part of breast cancer treatment, so that these patients can be provided with information that can keep them aware of the symptoms and allow them to obtain treatment quickly.

Awareness and diligence are crucial, because "the risk for lymphedema never goes away after surgery," explains Dr. Paskett. "We mainly see it develop in the first 12 to 18 months, but new cases continue to happen over time."

— Brittany Moya del Pino

|