Press Release

January 20, 2004

Emotion-Regulating Protein Lacking in Panic Disorder

Three brain areas of panic disorder patients are lacking in a key component of a chemical messenger system that regulates emotion, researchers at the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) have discovered. Brain scans revealed that a type of serotonin receptor is reduced by nearly a third in three structures straddling the center of the brain. The finding is the first in living humans to show that the receptor, which is pivotal to the action of widely prescribed anti-anxiety medications, may be abnormal in the disorder, and may help to explain how genes might influence vulnerability. Drs. Alexander Neumeister and Wayne Drevets, NIMH Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, and colleagues, report on their findings in the January 21, 2004 Journal of Neuroscience.

Each year, panic attacks strike about 2.4 million American adults “out of the blue,” with feelings of intense fear and physical symptoms sometimes confused with a heart attack. Unchecked, the disorder often sets in motion a debilitating psychological sequel syndrome of agoraphobia, avoiding public places. Panic disorder runs in families and researchers have long suspected that it has a genetic component. The new finding, combined with evidence from recent animal studies, suggests that genes might increase risk for the disorder by coding for decreased expression of the receptors, say the researchers.

NIMH grantee Dr. Rene Hen, Columbia University, and colleagues, reported in 2002 that a strain of gene “knockout” mice, engineered to lack the receptor during a critical period in early development, exhibit anxiety traits in adulthood, such as a reluctance to begin eating in an unfamiliar environment. More recent experiments with the knockout mice show that a popular SSRI (serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor) drug produces its anti-anxiety effects by stimulating the formation of new neurons in the hippocampus via the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor.

In the current study, Neumeister and Drevets used PET scans (positron emission tomography) to visualize 5-HT1A receptors in brain areas of interest in 16 panic disorder patients—seven of whom also suffered from major depression—and 15 matched healthy controls. A new radioactive tracer (FCWAY), developed by NIH Clinical Center PET scan scientists, binds to the receptors, revealing their locations and a numerical count by brain region. Subjects also underwent structural MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans, which were overlaid with their PET scan data to precisely match it with brain structures.

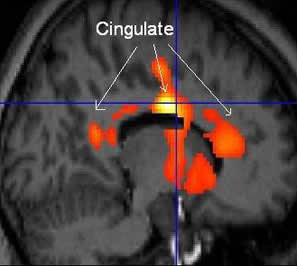

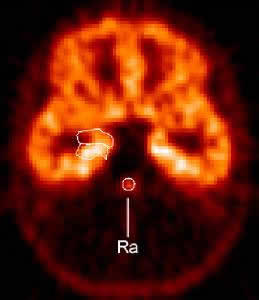

In the panic disorder patients, including those who also had depression, receptors were reduced by an average of nearly a third in the anterior cingulate in the front middle part of the brain, the posterior cingulate, in the rear middle part of the brain, and in the raphe, in the midbrain (See images below.). Previous functional brain imaging studies have implicated both the anterior and posterior cingulate in the regulation of anxiety. Stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors in the raphe regulates serotonin synthesis and release. In an earlier PET study of depressed patients, using a different tracer, Drevets and colleagues found less dramatic reductions of the receptor in the anterior and posterior cingulate, but a 41 percent reduction in the raphe. These findings add to evidence for overlap between depression and anxiety disorders.

Although animal experiments have shown that cortisol secretion triggered by repeated stress reduces expression of the gene that codes for the 5-HT1A receptor, such stress hormone elevations are usually not found in panic disorder. Noting the recent discovery of a variant of the 5-HT1A receptor gene linked to major depression and suicide, the researchers suggest that reduced expression of the receptor “may be a source of vulnerability in humans, and that abnormal function of these receptors appears to specifically impact the cortical circuitry involved in the regulation of anxiety.”

Other researchers who participated in the study are Drs. Earle Bain, Allison Nugent, Omer Bonne, David Luckenbaugh, Dennis Charney, NIMH; Richard Carson, William Eckelman, Peter Herscovitch, Warren G. Magnuson Clinical Center.

Statistically-analyzed PET scan data superimposed on structural MRI scan (front of brain is at right) shows areas in the anterior and posterior cingulate where panic disorder patients had nearly one third fewer serotonin 5-HT1A receptors compared to healthy control subjects. The lighter the color, the greater the difference between patients and controls.

Source: NIMH Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, 2004.

PET scan shows distribution of serotonin 5-HT1A receptors (front of brain is at top), which were reduced by about a third in the raphe (Ra) in panic disorder patients.

Source: NIMH Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, 2004

PET scans revealed that 16 panic disorder patients (circles), including 7 with comorbid depression (dots), averaged nearly a third fewer serotonin 5-HT1A receptors in three key brain areas, compared with 15 healthy controls (triangles).

Source: NIMH Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, 2004

#

NIMH is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Federal Government's primary agency for biomedical and behavioral research. NIH is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) mission is to reduce the burden of mental and behavioral disorders through research on mind, brain, and behavior. More information is available at the NIMH website.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) — The Nation’s Medical Research Agency — includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit the NIH website.