Press Release

June 10, 2003

Brain Cells Seen Recycling Rapidly To Speed Communications

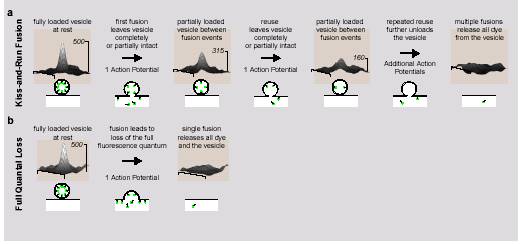

The tiny spheres inside brain cells that ferry chemical messengers into the synapse make their rounds much more expeditiously than once assumed, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded researchers have discovered. They used a dye to track the behavior of such synaptic vesicles in real time, in rat brain cells. Rather than fusing completely with the cell membrane and disgorging their dye contents all at once, brain vesicles more often remained intact, secreting only part of the tracer cargo in each of several repeated, fleeting contacts with the membrane, report Richard Tsien, D.Phil., Stanford University, and colleagues Alex Aravanis and Jason Pyle, in the June 5, 2003, Nature. Dubbed “kiss-and-run” recycling, this allows for more efficient communication between brain cells, suggest the researchers.Brain cells communicate in a process that begins with an electrical signal and ends with a neurotransmitter binding to a receptor on the receiving neuron. It lasts less than a thousandth of a second, and is repeated billions of times daily in each of the human brain's 100 billion neurons. Much of the action is happening inside the secreting cell. There, electrical impulses propel vesicles into the cell wall to spray the neurotransmitter into the synapse. Likened to soap bubbles merging, or bubbles bursting at the surface of boiling water, this process of membrane fusion may hold clues about what goes wrong in disorders of thinking, learning and memory, including schizophrenia and other mental illnesses thought to involve disturbances in neuronal communication.

Neurons must recycle a finite number of vesicles. In “classical” membrane fusion, the vesicle totally collapses and mixes with the cell membrane, requiring a complex and time-consuming retrieval and recycling process. Yet, Tsien and colleagues point out that this process was discovered in huge neurons, such as those in squid giant synapses, with tens or hundreds of thousands of vesicles per nerve terminal. By contrast, they find that the comparatively tiny nerve terminals of the mammalian brain must make do with only about 30 functional vesicles—hardly enough to keep up with the split-second demands of synaptic communication if vesicles can only be replenished via the one-shot classical process, they argue. Hence, the “kiss-and-run” hypothesis.

To observe single vesicles in action, Tsien and colleagues put a fluorescent dye into nerve terminals in cultured neurons from the rat hippocampus, a key memory hub involved in learning. The dye was later washed out of neuronal membranes, but it remained trapped in the vesicles, enabling the researchers to take snapshots of their activity at synapses following electrical stimulation, using a microscope, pulses of fluorescent light, and a CCD imaging device.

When they tracked single vesicles following stimulation, they usually observed a series of abrupt and lasting—albeit partial—decreases in fluorescence, indicating multiple fusion events. Yet, only rarely was there a full loss of fluorescence, indicating full classical collapse.

“A likely explanation is that most fusion events were simply too brief to permit dye to escape completely,” noted Tsien and colleagues. “After rapid retrieval by a process that maintained vesicle integrity, vesicles remained available for repeated fusion, supporting their repeated re-use for neurotransmitter release. Vesicles are readily refilled with neurotransmitter so each fusion can send a meaningful signal. Together, brief fusion, rapid retrieval and re-use would enable small nerve terminals of the central nervous system to get full mileage from their limited set of vesicles.”

Only at times of “all-out vesicular mobilization” would most of the hippocampal neuron vesicles likely shift to the classical mode of membrane fusion, they concluded.

Another study published in the same issue of Nature by Dr. Charles Stevens, The Salk Institute, and colleagues, also found evidence in support of “kiss-and-run.”

Rather than disgorging their cargo of tracer dye (green dots) all at once and merging with the cell membrane (b), the researchers observed that synaptic vesicles usually meter it out in partial steps over the course of several fleeting contacts with the membrane in a process dubbed “kiss-and-run” fusion (a). The fusion events occur following an action potential, or electrical change.

Source: Richard Tsien, D.Phil.

Stanford University

NIMH is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Federal Government's primary agency for biomedical and behavioral research. NIH is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) mission is to reduce the burden of mental and behavioral disorders through research on mind, brain, and behavior. More information is available at the NIMH website.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) — The Nation’s Medical Research Agency — includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit the NIH website.