Press Release

April 23, 2008

Human Brain Appears “Hard-Wired” for Hierarchy

Scans Hint at Why It Can Be Unhealthy Even at the Top

Human imaging studies have for the first time identified brain circuitry associated with social status, according to researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health. They found that different brain areas are activated when a person moves up or down in a pecking order – or simply views perceived social superiors or inferiors. Circuitry activated by important events responded to a potential change in hierarchical status as much as it did to winning money.

“Our position in social hierarchies strongly influences motivation as well as physical and mental health,” said NIMH Director Thomas R Insel, M.D. “This first glimpse into how the brain processes that information advances our understanding of an important factor that can impact public health.”

Caroline Zink, Ph.D., Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues of the NIMH Genes Cognition and Psychosis Program, report on their functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study in the April 24, 2008, issue of the journal Neuron. Meyer-Lindenberg is now director of Germany’s Central Institute of Mental Health.

Prior studies have shown that social status strongly predicts health. Animals chronically stressed by their hierarchical position have high rates of cardiovascular and depression/anxiety-like syndromes. A classic study of British civil servants found that the lower one ranked, the higher the odds for developing cardiovascular disease and dying early. Lower social rank likely compromises health through psychological effects, such as by limiting control over one’s life and interactions with others. However, in hierarchies that allow for more upward mobility, those at the top who stand to lose their positions can have higher risk for stress-related illness. Yet little is known about how the human brain translates such factors into health risk.

To find out, the NIMH researchers created an artificial social hierarchy in which 72 participants played an interactive computer game for money. They were assigned a status that they were told was based on their playing skill. In fact, the game outcomes were predetermined and the other “players” simulated by computer. While their brain activity was monitored by fMRI, participants intermittently saw pictures and scores of an inferior and a superior “player” they thought were simultaneously playing in other rooms.

Although they knew the perceived players’ scores would not affect their own outcomes or reward –and were instructed to ignore them – participants’ brain activity and behavior were highly influenced by their position in the implied hierarchy.

“The processing of hierarchical information seems to be hard-wired, occurring even outside of an explicitly competitive environment, underscoring how important it is for us,” said Zink.

Key study findings included:

- The area that signals an event’s importance, called the ventral striatum, responded to the prospect of a rise or fall in rank as much as it did to the monetary reward, confirming the high value accorded social status.

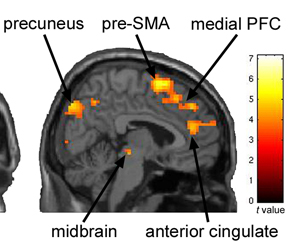

- Just viewing a superior human “player,” as opposed to a perceived inferior one or a computer, activated an area near the front of the brain that appears to size people up – making interpersonal judgments and assessing social status. A circuit involving the mid-front part of the brain that processes the intentions and motives of others and emotion processing areas deep in the brain activated when the hierarchy became unstable, allowing for upward and downward mobility.

- Performing better than the superior “player” activated areas higher and toward the front of the brain controlling action planning, while performing worse than an inferior “player” activated areas lower in the brain associated with emotional pain and frustration.

- The more positive the mood experienced by participants while at the top of an unstable hierarchy, the stronger was activity in this emotional pain circuitry when they viewed an outcome that threatened to move them down in status. In other words, people who felt more joy when they won also felt more pain when they lost.

“Such activation of emotional pain circuitry may underlie a heightened risk for stress-related health problems among competitive individuals,” suggested Meyer-Lindenberg.

In collaboration with other NIMH researchers, Zink and colleagues are planning follow-up studies to explore brain activity in response to the experimental social hierarchy in patients with mental illnesses like schizophrenia or autism, which are marked by social and thinking deficits. The researchers will also be exploring whether particular gene variants might differentially affect brain responses in similar experiments.

Also participating in the study were Yunxia Tong, Qiang Chen, Danielle Bassett, and Jason Stein, NIMH.

Cover art for Neuron.

Source: Lydia Kibiuk and Ethan Tyler, NIH Division of Medical Arts.

Brain activity was much higher in key brain centers when participants viewed a superior player in an unstable social hierarchy – when participants had the possibility of upward mobility.

Source: Caroline Zink, Ph.D., NIMH Genes Cognition and Psychosis Program

When participants experienced an outcome that could increase their status and have them become superior players, activity increased in circuitry at the top front of the brain that controls the intention to do something, suggesting that rising in a hierarchy makes one more action-oriented.

Source: Caroline Zink, Ph.D., NIMH Genes Cognition and Psychosis Program

As they played games in the MRI scanner, pictures with rankings of other players and updated outcomes periodically flashed on the screen. Situations that could signal a fall in status activated circuitry known to process emotional pain and frustration.

Source: Caroline Zink, Ph.D., NIMH Genes Cognition and Psychosis Program

References

Zink CF, Tong Y, Chen Q, Bassett D, Stein JL, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Know your place: neural processing of social hierarchy in humans. Neuron. 2008 Apr 24;

Sapolsky RM. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health.Science. 2005 Apr 29;308(5722):648-52.Review. PMID: 15860617

Marmot MG. Status syndrome: a challenge to medicine. JAMA. 2006 Mar 15;295(11):1304-7. No abstract available. PMID: 16537740

Listen to a podcast about this press release

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) mission is to reduce the burden of mental and behavioral disorders through research on mind, brain, and behavior. More information is available at the NIMH website.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) — The Nation’s Medical Research Agency — includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit the NIH website.