Stem Cell Basics

- Introduction

- What are the unique properties of all stem cells?

- What are embryonic stem cells?

- What are adult stem cells?

- What are the similarities and differences between embryonic and adult stem cells?

- What are the potential uses of human stem cells and the obstacles that must be overcome before these potential uses will be realized?

- Where can I get more information?

IV. What are adult stem cells?

An adult stem cell is an undifferentiated cell found among differentiated cells in a tissue or organ, can renew itself, and can differentiate to yield the major specialized cell types of the tissue or organ. The primary roles of adult stem cells in a living organism are to maintain and repair the tissue in which they are found. Some scientists now use the term somatic stem cell instead of adult stem cell. Unlike embryonic stem cells, which are defined by their origin (the inner cell mass of the blastocyst), the origin of adult stem cells in mature tissues is unknown.

Research on adult stem cells has recently generated a great deal of excitement. Scientists have found adult stem cells in many more tissues than they once thought possible. This finding has led scientists to ask whether adult stem cells could be used for transplants. In fact, adult blood forming stem cells from bone marrow have been used in transplants for 30 years. Certain kinds of adult stem cells seem to have the ability to differentiate into a number of different cell types, given the right conditions. If this differentiation of adult stem cells can be controlled in the laboratory, these cells may become the basis of therapies for many serious common diseases.

The history of research on adult stem cells began about 40 years ago. In the 1960s, researchers discovered that the bone marrow contains at least two kinds of stem cells. One population, called hematopoietic stem cells, forms all the types of blood cells in the body. A second population, called bone marrow stromal cells, was discovered a few years later. Stromal cells are a mixed cell population that generates bone, cartilage, fat, and fibrous connective tissue.

Also in the 1960s, scientists who were studying rats discovered two regions of the brain that contained dividing cells, which become nerve cells. Despite these reports, most scientists believed that new nerve cells could not be generated in the adult brain. It was not until the 1990s that scientists agreed that the adult brain does contain stem cells that are able to generate the brain's three major cell types—astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, which are non-neuronal cells, and neurons, or nerve cells.

A. Where are adult stem cells found and what do they normally do?

adult stem cells have been identified in many organs and tissues. One important point to understand about adult stem cells is that there are a very small number of stem cells in each tissue. Stem cells are thought to reside in a specific area of each tissue where they may remain quiescent (non-dividing) for many years until they are activated by disease or tissue injury. The adult tissues reported to contain stem cells include brain, bone marrow, peripheral blood, blood vessels, skeletal muscle, skin and liver.

Scientists in many laboratories are trying to find ways to grow adult stem cells in cell culture and manipulate them to generate specific cell types so they can be used to treat injury or disease. Some examples of potential treatments include replacing the dopamine-producing cells in the brains of Parkinson's patients, developing insulin-producing cells for type I diabetes and repairing damaged heart muscle following a heart attack with cardiac muscle cells.

B. What tests are used for identifying adult stem cells?

Scientists do not agree on the criteria that should be used to identify and test adult stem cells. However, they often use one or more of the following three methods: (1) labeling the cells in a living tissue with molecular markers and then determining the specialized cell types they generate; (2) removing the cells from a living animal, labeling them in cell culture, and transplanting them back into another animal to determine whether the cells repopulate their tissue of origin; and (3) isolating the cells, growing them in cell culture, and manipulating them, often by adding growth factors or introducing new genes, to determine what differentiated cells types they can become.

Also, a single adult stem cell should be able to generate a line of genetically identical cells—known as a clone—which then gives rise to all the appropriate differentiated cell types of the tissue. Scientists tend to show either that a stem cell can give rise to a clone of cells in cell culture, or that a purified population of candidate stem cells can repopulate the tissue after transplant into an animal. Recently, by infecting adult stem cells with a virus that gives a unique identifier to each individual cell, scientists have been able to demonstrate that individual adult stem cell clones have the ability to repopulate injured tissues in a living animal.

C. What is known about adult stem cell differentiation?

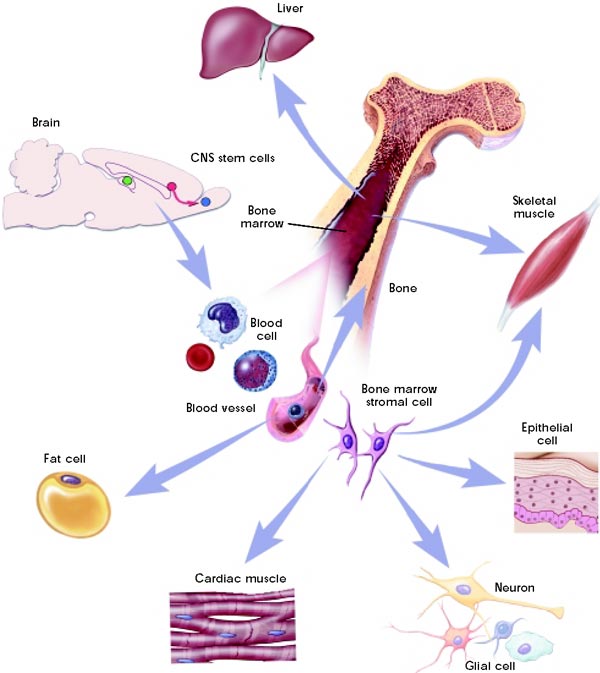

Figure 2. Hematopoietic and stromal stem cell differentiation. Click here for larger image.

As indicated above, scientists have reported that adult stem cells occur in many tissues and that they enter normal differentiation pathways to form the specialized cell types of the tissue in which they reside. Adult stem cells may also exhibit the ability to form specialized cell types of other tissues, which is known as transdifferentiation or plasticity.

Normal differentiation pathways of adult stem cells. In a living animal, adult stem cells can divide for a long period and can give rise to mature cell types that have characteristic shapes and specialized structures and functions of a particular tissue. The following are examples of differentiation pathways of adult stem cells (Figure 2).

- Hematopoietic stem cells give rise to all the types of blood cells: red blood cells, B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils, monocytes, macrophages, and platelets.

- Bone marrow stromal cells (mesenchymal stem cells) give rise to a variety of cell types: bone cells (osteocytes), cartilage cells (chondrocytes), fat cells (adipocytes), and other kinds of connective tissue cells such as those in tendons.

- neural stem cells in the brain give rise to its three major cell types: nerve cells (neurons) and two categories of non-neuronal cells—astrocytes and oligodendrocytes.

- Epithelial stem cells in the lining of the digestive tract occur in deep crypts and give rise to several cell types: absorptive cells, goblet cells, Paneth cells, and enteroendocrine cells.

- Skin stem cells occur in the basal layer of the epidermis and at the base of hair follicles. The epidermal stem cells give rise to keratinocytes, which migrate to the surface of the skin and form a protective layer. The follicular stem cells can give rise to both the hair follicle and to the epidermis.

Adult stem cell plasticity and transdifferentiation. A number of experiments have suggested that certain adult stem cell types are pluripotent. This ability to differentiate into multiple cell types is called plasticity or transdifferentiation. The following list offers examples of adult stem cell plasticity that have been reported during the past few years.

- Hematopoietic stem cells may differentiate into: three major types of brain cells (neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes); skeletal muscle cells; cardiac muscle cells; and liver cells.

- Bone marrow stromal cells may differentiate into: cardiac muscle cells and skeletal muscle cells.

- Brain stem cells may differentiate into: blood cells and skeletal muscle cells.

Current research is aimed at determining the mechanisms that underlie adult stem cell plasticity. If such mechanisms can be identified and controlled, existing stem cells from a healthy tissue might be induced to repopulate and repair a diseased tissue (Figure 3).

D. What are the key questions about adult stem cells?

Many important questions about adult stem cells remain to be answered. They include:

- How many kinds of adult stem cells exist, and in which tissues do they exist?

- What are the sources of adult stem cells in the body? Are they "leftover" embryonic stem cells, or do they arise in some other way? Why do they remain in an undifferentiated state when all the cells around them have differentiated?

- Do adult stem cells normally exhibit plasticity, or do they only transdifferentiate when scientists manipulate them experimentally? What are the signals that regulate the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells that demonstrate plasticity?

- Is it possible to manipulate adult stem cells to enhance their proliferation so that sufficient tissue for transplants can be produced?

- Does a single type of stem cell exist—possibly in the bone marrow or circulating in the blood—that can generate the cells of any organ or tissue?

- What are the factors that stimulate stem cells to relocate to sites of injury or damage?

Figure 3. Plasticity of adult stem cells. Click here for larger image.

Previous | IV. What are adult stem cells? | Next

Previous | IV. What are adult stem cells? | Next