| Design for Inclusion: Creating

a New Marketplace--Industry White Paper

National

Council on Disability

1331 F Street, NW, Suite 850

Washington, DC 20004

202-272-2004 Voice

202-272-2074 TTY

202-272-2022 Fax

Lex Frieden, Chairperson

October 28, 2004

This report is also available in alternative formats

and on NCD’s award-winning Web site (http://www.ncd.gov/).

The views contained in the report do not necessarily

represent those of the administration, as this and all NCD reports

are not subject to the A-19 executive branch review process.

National Council on Disability

Members and Staff

Members

Lex Frieden, Chairperson, Texas

Patricia Pound, First Vice Chairperson, Texas

Glenn Anderson, Ph.D., Second Vice Chairperson, Arkansas

Milton Aponte, J.D., Florida

Robert R. Davila, Ph.D., New York

Barbara Gillcrist, New Mexico

Graham Hill, Virginia

Joel I. Kahn, Ph.D., Ohio

Young Woo Kang, Ph.D., Indiana

Kathleen Martinez, California

Carol Novak, Florida

Anne M. Rader, New York

Marco Rodriguez, California

David Wenzel, Pennsylvania

Linda Wetters, Ohio

Staff

Ethel D. Briggs, Executive Director

Jeffrey T. Rosen, General Counsel and Director of Policy

Mark S. Quigley, Director of Communications

Allan W. Holland, Chief Financial Officer

Julie Carroll, Attorney Advisor

Joan M. Durocher, Attorney Advisor

Martin Gould, Ed.D., Senior Research Specialist

Geraldine Drake Hawkins, Ph.D., Program Analyst

Pamela O’Leary, Interpreter

Brenda Bratton, Executive Assistant

Stacey S. Brown, Staff Assistant

Carla Nelson, Office Automation Clerk

Acknowledgments

The National Council on Disability (NCD) wishes to

express its appreciation to W. Bradley Fain of Georgia Tech Research

Institute (GTRI), who was the principal investigator for this project.

Researchers in GTRI’s Electronic Systems Laboratory performed

the work documented in this report. NCD acknowledges the contributions

of Steve Jacobs of the Ideal Group, who performed the market definition

and research for this report. NCD also acknowledges the participation

of the industry partners that supported the industry study portion

of this research. The industry partners provided invaluable insight

into the impact of Section 508 on business and the barriers and

facilitators relating to the adoption of universal design principles.

NCD also acknowledges the donation of equipment and services utilized

during the user study portion of the research. The following companies

provided products and services, at no cost to the project, for user

testing: HP, Nokia, and SENCORE Electronic Test Equipment.

NCD would also like to acknowledge the efforts of

Gerry Field, WGBH Boston, for providing a closed caption test stream

used in user testing.

Contents

National Council on Disability Members

and Staff

Acknowledgments

I. Executive Summary

Important Findings and Recommendations

II. Market Definition and Research

Definition of the Market Environment

Customer Analysis

Analysis of the International Market

Analysis of Market Trends

III. Industry Study

Analysis of Facilitators and Barriers

to Accessible Design

Industry Study Data Collection

Methodology

Analysis of Industry Data: Factors

Influencing Adoption of UD Practices

Analysis of the Industry Study Findings

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

Bibliography

LIST OF TABLES

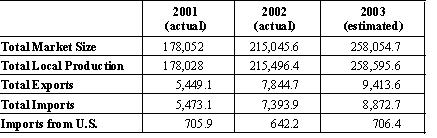

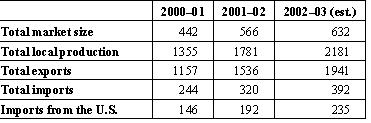

Table 1: China's Information Technology

Market

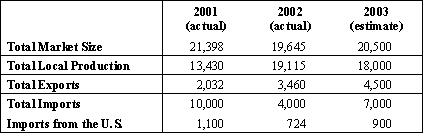

Table 2: China's Telecommunication

Equipment Market

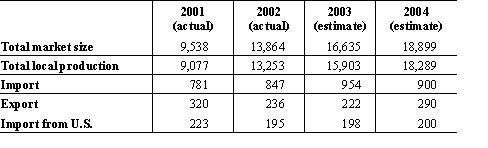

Table 3: China's Packaged Software

Import and Export Market

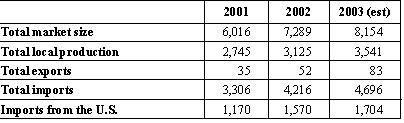

Table 4: Other Promising Telecommunication

Equipment Sub-Sectors

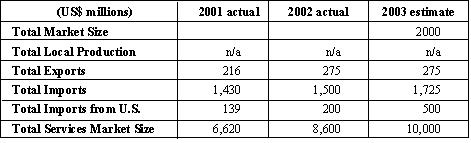

Table 5: Total Combined Market for

Telecommunications Equipment in India

Table 6: Computers and Peripherals

in India

Table 7: Information Technology in

India

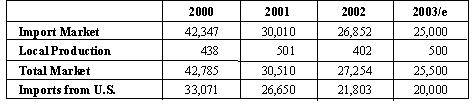

Table 8: Russia's Telecommunications

Equipment Market

Table 9: Computers, Peripherals,

and Software in Russia

Table 10: Electronic Components

Imported from the U.S. in 2002 (US$ millions)

Table 11: Electronic Components

Imported from the U.S. to Mexico in 2002

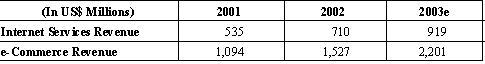

Table 12: Mexican Internet and E-Commerce

Revenues

Table 13: Mexican Computers

Table 14: Market Size Estimate for

the Turkish Telecommunications Services Sector

Table 15: Market Size Estimate for

the Turkish Telecommunications Equipment Sector

Table 16: Turkey's Information Technology

Market

Executive

Summary

Designing with access in mind can significantly increase

the size of targeted markets for electronic and information technology

(E&IT). Good business practice dictates that designers and engineers

avoid unintentionally excluding large populations of consumers from

accessing and using the E&IT they develop and manufacture. People

with disabilities are at the highest risk of exclusion. Other consumer

groups are also at risk. They are—

• Individuals 65+ years old

• Consumers living in low-bandwidth

information infrastructures

• People who never learned to read

• Users of English as a Second Language

(ESL)

• Tourists and people living in multilingual

societies

• Consumers living in high-density

populations

Designing with access in mind can be accomplished

through universal design (UD). Universal design is a process to

ensure that E&IT is inclusive, accessible, and usable by everyone,

including people with disabilities. Accessible design is a step

forward when developing E&IT products, but it tends to lead

to technologies that will be used separately, or in addition to,

the main E&IT product, which diminishes the effectiveness of

designing for all. Incorporating UD processes when developing E&IT

is one solution to accommodating people with disabilities that also

improves the usability of the products for the rest of the population.

The National Council on Disability (NCD) undertook

this research to understand the market for universally designed

mainstream consumer products and services, document successful UD

development processes, understand consumer needs, understand UD

facilitators and barriers, and identify and address current issues

in universal design. This research comes at a time when understanding

and incorporating UD into the development process are most crucial.

We are in the window of opportunity for implementing section 508.

If progress is not made quickly in improving the skills of government

and industry employees on accessibility issues, the window will

soon shut with little having been accomplished. If industry does

not see that federal agencies are serious about implementing section

508 in a consistent manner, companies will shift the monetary and

human resources needed for improving accessibility to product development

opportunities that offer a higher return on investment. Progress

must be made now, and the purpose of this report is to present the

information and recommendations that will guide this progress.

Through this research, NCD aims to educate designers

and manufacturers about how electronic and information technology

intersects with the needs of individuals with disabilities. In addition

to providing knowledge about disabilities, we see the importance

here and now of educating individuals on universal design. Currently,

many business people have never heard of UD, and many of those who

have do not understand that it is more than just a design for disability.

This research aims to provide businesses with the knowledge of UD

methods they need to clearly see how their complex products can

be made accessible in a cost-effective way.

As part of this research, six product lines were

analyzed from the telecommunications, software, consumer electronics,

and digital services industries for both accessibility and usability.

We estimated how useful these products are to people with disabilities

and whether the products conformed to section 508 standards and

section 255 guidelines. We were able to present recommendations

for improving such products. At a time when the incorporation of

universal design is crucial, NCD hopes that the information provided

in this report will motivate and drive the development of more universally,

accessibly designed E&IT.

Important Findings and

Recommendations

User Study. The purpose

of the user study was to document and understand user experiences

with the six product lines under study. The experiences and thoughts

of the consumer with a disability provided important insight into

the future design of accessible products and can potentially influence

the universal design process. The key findings of the user study

are as follows:

• Users with disabilities are often

asked to pay high prices for phones with feature sets that are

not useful to them.

• Rapid changes in technology often

cause decreases in accessibility.

• Users are reluctant to adopt technologies

that have proven frustrating in the past.

• Users have difficulty finding devices

that match their functional capabilities because of the lack of

familiarity sales associates have with accessibility features.

• Users are reluctant to invest in

technologies that have an unproven accessibility record.

• Accessibility solutions must consider

the needs of the individual with disabilities.

Substantial increases in accessibility will be required

before increased sales to members of the disability community are

realized.

Product Analysis. A detailed

product line analysis was conducted for each of the product lines

selected for study. The purpose of this research was to document

accessibility issues that prevent people with disabilities from

fully accessing the selected products and to document accessibility

features that either are currently offered or could be offered by

manufacturers. The end result of this product analysis was the assignment

of an accessibility grade to each product line for each disability

group. These grades may be useful to designers and manufacturers

to identify the target populations that should be consulted during

the design process so that more accessible design features are incorporated

into new products.

Industry Study. The purpose

of the industry study was to document UD practices within industries

represented by the six product lines selected for study. Five categories

of facilitators and barriers to accessible design were examined:

design, organizational, informational, financial, and legal. A discussion

of these barriers and facilitators as experienced by the six companies

is included in this section.

In addition, 11 business concerns were identified

as having an influence on UD practices within an organization. Each

business concern had a different level of influence, depending on

the strength of the other factors. The factors influencing the adoption

of UD practices included the business case, strategy and policy,

demand and legislation, marketing and sales, research, design, testing,

resource allocation and funding, organization and staff, training,

and the customer and consideration of people with disabilities.

All the companies that participated in the industry

study have made strategic decisions to address the accessibility

of their products and services. A few of the companies had long-standing

accessibility programs that were reinvigorated by the technical

requirements of section 508. Other companies initiated their accessibility

activities while planning for their response to section 508. In

both cases, section 508 clearly has had an impact on the way accessibility

and UD are being addressed by industry. The industry study found

that the most common approaches to addressing accessibility issues

are—

• Increasing awareness of employees

• Integrating accessibility requirements

into the design process

• Performing accessibility verification

testing

• Establishing an accessibility program

office

Discussion. Through this

research, we have come to better understand the market for universally

designed mainstream consumer products and services, documented successful

universal design development processes, achieved a better understanding

of consumer needs, analyzed UD facilitators and barriers, and identified

and addressed current issues in universal design. This research

program has found that—

• A market for universally designed

products and services exists.

• UD principles can be easily incorporated

into current design practices.

• Products designed to be accessible

sometimes do not meet the needs of users.

• Legislation is currently both a facilitator

and a barrier to UD.

• Many barriers to UD remain and must

be addressed before significant progress can be made.

Several important recommendations can be made from

this research for designers, developers, federal agencies, and companies

striving to incorporate universal design into their development

process:

Strategies for Government and Industry to Promote

Universal Design

Recommendation #1. Use standards

(government or industry) to prohibit nonessential features that

pose accessibility problems unless an alternative interface that

solves the problem is provided.

Recommendation #2. Use standards

(government or industry) to eliminate interoperability problems

that create accessibility problems.

Recommendation #3. Use market

forces to regulate features that pose intermediate levels of accessibility

problems. Require labeling and other information to be provided,

and allow recourse through tort (warranty) as well as through general

demand, as reflected in consumer purchases.

Recommendation #4. Develop

training materials and educational articles documenting the market

potential for UD products and services.

Strengthening the Impact of Section 508

Section 508 was developed to govern the purchase

of accessible electronic and information technology purchased by

the Federal government. Despite having been in place for nearly

three years, section 508 has yet to reach its potential. One of

the greatest shortfalls of Section 508 is the lack of understanding

of and attention to the functional performance requirements.

Recommendation #5. Institute

procedures designed to ensure that due diligence is given to section

508 procurement requirements. Perform an internal analysis of the

impact of section 508 on the procurement of actual products. Publish

the results of the analysis as a way of convincing industry that

the Federal Government is committed to section 508.

Recommendation #6. Consider

requesting supporting evidence for claims made on voluntary product

accessibility templates (VPATs) from all vendors responding to bid

proposals.

Recommendation #7. Develop

a quick accessibility checklist for specific product lines likely

to be procured by the Federal Government. The quick accessibility

checklist would assist procurement officials in market research

by providing them with a list of items that they can inspect themselves

when procuring products. The checklist would be tailored to specific

product lines and would not require detailed expertise to evaluate.

Recommendation #8. Develop

guidance for reporting conformance with functional performance criteria

guidelines.

Recommendation #9. Support

the coordination of state and local government adoption of section

508 technical requirements. Provide state and local governments

with documents and training programs designed to ensure unification

of technical requirements.

Recommendation #10. Study

and document the nontechnical aspects of accessibility, including

social, psychological, and organizational accessibility. Promote

UD solutions that consider all aspects of accessibility.

Promoting the Inclusion of Universal Design in Industry

Practices

Companies are not aware of the design process modifications

needed to incorporate universal design principles. The Federal Government

should support the refinement of specific design process interventions

that can easily be incorporated.

Recommendation #11. Develop,

test, and disseminate methodologies for integrating UD into existing

design practices.

Recommendation #12. Support

the development of university-level training materials that could

be incorporated into the curriculums of existing design-oriented

degree programs. The training materials should include awareness-expanding

videos and other teaching resources that illustrate the potential

impact of key design process interventions on the lives of people

with disabilities and other beneficiaries of UD.

Recommendation #13. Develop,

test, and disseminate design reference users to illustrate the range

of functional capabilities and limitations typical among people

with disabilities. Design reference users (popular in specifying

the target population in Department of Defense acquisitions) is

a set of descriptions of prototypical users who, taken together,

express the range of functional capabilities and limitations of

the population that must be accommodated by the design project.

The use of design reference users would greatly simplify the need

for designers to research and integrate information pertaining to

the functional limitations and capabilities of people with disabilities.

Recommendation #14. Develop

a standard methodology for testing accessibility and comparing the

accessibility of similar products.

Recommendation #15. Coordinate

with industry to promote the integration of accessibility concepts,

principles, and guidelines into the development tools used by designers

to develop products.

Creating a New Marketplace

Consumers with disabilities find many E&IT products

to be inaccessible. A sizeable un-tapped market for universal design

products and services exists. However, few companies appreciate

the size of the market or know how to tap its potential.

Recommendation #16. Develop

an information clearinghouse where users can obtain information

about accessibility issues and the features designed to address

the issues for specific product lines. Educate consumers on how

to shop for UD products and services. List vendor resources where

consumers can obtain more information about UD products.

Recommendation #17. Develop

marketing strategies and approaches that will facilitate a connection

with people with disabilities.

Recommendation #18. Train

people with disabilities to become subject-matter experts for the

purpose of participating in design focus groups and accessibility

evaluations.

Recommendation #19. Create

job-related outcomes for bulk purchasers for the successful procurement

of products and services with UD features.

Conclusions

People with disabilities want to use the same products

that everyone else uses. They do not want to be limited to specialized

products that are more costly. Implementation of UD is the best

way to satisfy this desire of people with disabilities, while also

providing more cost-effective products for all users. While it is

impossible to satisfy the needs of all users, products and services

that come closer to accommodating a variety of physical and cognitive

differences will benefit both users and companies.

A full version of this report, including methodology,

can be found online at www.ncd.gov.

II. Market

Definition and Research

Electronic and information technology is driving

the creation of new communities that are forever changing the way

people live, learn, work, and play. Companies are increasingly expanding

their presence in emerging markets. Businesses are serving populations

they have never served before. Every consumer is different. No two

people have the same set of characteristics, learning styles, abilities,

experiences, or educational backgrounds. Developing products that

accommodate the wants, needs, and preferences of as many individual

consumers as is technically possible and economically feasible can

greatly enhance a company’s competitive advantage.

Designing with access in mind can significantly increase

the size of E&IT markets on a global basis. Good business practices

dictate that designers and engineers avoid excluding large groups

of consumers from accessing and using E&IT. Groups at the highest

risk of unintentional exclusion are

• People with disabilities

• Individuals 65+ years old

• Consumers living within low-bandwidth

information infrastructures

• Users of English as a Second Language

(ESL)

• Tourists traveling to nonnative language

destinations

• Consumers living in high-density

populations

This market analysis examined many aspects of manufacturing

“more accessibly designed” E&IT. This analysis was

intended to help answer questions like the following:

• Is there a market for more accessibly

designed products?

• Does the capacity exist to develop

more accessibly designed products in each of the presented product

lines?

• What factors influence the market

for more accessibly designed products for each of the product

lines presented?

All of the product lines reviewed in this report

are manufactured by members of the E&IT industry. Naturally,

in order for these products to be manufactured, the E&IT industry

must exist. In order to exist, it must be profitable. A question

often asked by the disability community is, “How can we ensure

that the E&IT products and services being manufactured are accessible

to people with disabilities?” E&IT manufacturers often

pose this same question using different words. They ask, “How

can we ensure that the E&IT products and services we manufacture

are accessible and usable by as many people as is technically possible

and economically feasible without the need for customization?”

The questions are different. The motivations are different. The

market drivers are different. The solutions can be remarkably similar.

Definition of the Market

Environment

Historically, the primary forces driving the manufacture

of more accessible E&IT products and services have been legal,

moral, social, and ethical. The assumption was that if legal, moral,

social, and ethical issues no longer existed, then the motivation

to manufacture more accessible E&IT would all but disappear.

The next two sections discuss the reasons why nothing could be further

from the truth.

In contrast to the historical notion of the primary

forces driving the manufacture of accessible E&IT, in actuality,

a majority of the forces driving demand for more accessibly designed

E&IT fall into the following five categories:

Market Forces

Market forces consistently drive the demand for more

accessibly designed E&IT. Market forces include the need to

respond to consumer behavior, the work of federal agencies, legislation

mandating developments in the accessibility of E&IT, changing

marketing philosophies (from mass marketing to a one-on-one marketing

philosophy), competition within the market, emerging technology

trends, and economic expansion. These market forces are discussed

below in terms of how they drive the markets for more accessibly

designed E&IT products.

Consumer Behavior

E&IT is prevalent in schools, libraries, individuals’

homes, work environments, places of recreation, banks, and even

supermarkets. It is because of this widespread presence that consumers

are more technically literate than they were five years ago. Devices

such as cell phones, PDAs, voice recognition systems, and the wireless

Web enable us to carry our offices with us when we travel. We are

more mobile now than ever before. Consumers have become accustomed

to getting the information they need when they need it and where

they want it. This has created an expectation of immediacy. When

consumers don’t get what they want quickly, they become impatient.

E&IT designers need to respond to consumer behavior by providing

products and services that not only meet, but exceed the high expectations

of a technically literate, mobile, consumer base. Increasing the

accessibility of information services and mobile technologies increases

access to the information demanded by consumers with high expectations.

Federal Government

The Federal Government serves as a catalyst for more

accessibly designed E&IT products through its buying power,

the development of legislation, and the support of assistive technology

(AT) accommodation labs. Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act amendments

of 1998 mandates the purchase of accessibly designed E&IT. As

a result, all federal agencies appointed Section 508 coordinators

(Section 508, 2003). Those coordinators are responsible for organizing

and supporting the implementation of Section 508 within their respective

departments and agencies, and they serve as the central point of

contact for information concerning accessibility issues and solutions.

In addition to Section 508, other legislation provides guidelines

for designing more accessible E&IT. The Access Board developed

the ADA Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities (ADAAG),

and the Telecommunications Act Accessibility Guidelines (Section

255) mandate the design of more accessible E&IT products and

services. Presidential initiatives also drive the design of more

accessible E&IT. These initiatives include the President’s

New Freedom Initiative (White House, 2001), the No Child Left Behind

Initiative (U.S. House of Representatives, 2002), and the disabilityinfo.gov

Web site (DisabilityInfo.gov, 2003).

In addition to these acts and initiatives, many federal

agencies have created AT accommodation labs. These labs serve as

focal points for information regarding accommodations, disabilities,

and AT.

Clearly, the Federal Government is an important market

force for driving accessibility requirements.

Marketing Philosophies

Marketing philosophies have changed radically over

the past 35 years. The marketing philosophy of the 1960s was mass

marketing (Mass Marketing Definition, 2003), in which the seller

views the market as a homogeneous whole and, therefore, has only

one marketing program (the same product, the same price, the same

promotion, and the same distribution system) for everyone in the

population. This type of marketing is also referred to as unsegmented

or undifferentiated marketing.

Marketing philosophies of the 1970s included product

line extension (Product Line Stretching Definition, 2003) and market

segmentation (Market Segmentation Definition, 2003). Product line

extension adds depth to an existing product line by introducing

new products in the same product category. Market segmentation is

the division of a totally heterogeneous market into groups or sectors

with relatively homogeneous needs and wants.

In the 1980s, the marketing philosophy shifted to

one of niche marketing (Niche Marketing Definition, 2003). Niche

marketing or concentrated marketing is a marketing segmentation

strategy in which the firm concentrates all of its efforts and resources

on serving one segment of the market.

In the 1990s, value-added marketing became popular.

Value-added marketing is a strategy in which a company buys products,

customizes them for a particular application, and then resells them.

There was also a shift toward marketing to individual customers

rather than the larger mass. Don Peppers and Martha Rogers invented

the phrase “one-to-one” marketing (Peppers and Rogers,

1997) to illustrate the revolutionary concept of treating different

customers differently. One-to-one marketing supports the establishment

of permanent relationships with your customers. One-to-one subscribes

to providing products and services to customers according to their

individual wants, needs, and preferences. “Share of customer”

replaces market share. The marketing focus shifts from institutions

to individual consumers.

Once a company acquires the knowledge and experience

required to manufacture more accessibly designed E&IT, it can

take an asset marketing approach (Asset-Based Marketing Definition,

2003) to providing their E&IT products globally. Asset marketing

uses the knowledge and skills a company has already developed as

the basis for growth. For example, a company that is skilled in

developing kiosks that are accessible to people who are blind can

market kiosks designed in a similar manner to countries that have

high populations of people who never learned to read. This global

marketing (Global Marketing Definition, 2003) philosophy enables

companies to sell the same, or very similar, products to world markets

with essentially the same promotion. This marketing approach is

also commonly referred to as international marketing.

Competition

Competition in the E&IT industry is fierce. The

industry is constantly looking for ways to increase efficiency,

competitive advantage, sales, market shares, and profitability.

It is also looking to cut costs. Businesses are constantly developing

new and innovative products and services with the hope of achieving

these objectives, and adding functionality that enhances the accessibility

and usability of a product can be very beneficial. In extremely

competitive markets, several companies have correctly identified

UD as a potential market discriminator. When highly similar product

lines are all competing for the same customer, a product designed

with access in mind may have the needed advantage required to outbid

the competitors.

Technology Trends

A variety of rising mainstream technology trends

fuels the need for more accessibly designed E&IT. The functionalites

of multiple individual devices are now being integrated into a single

device, including pagers, cell phones, PDAs, palmtop computers,

smart phones, and MP3 players. This is creating a dependence on

one device to accomplish multiple functions. Thus, if not more accessibly

designed, this multiple functionality precludes the use of such

devices by certain segments of the population, e.g., people 65+

years of age. Developing and manufacturing an accessible interface

for a device that provides multiple functions is less expensive

than developing and manufacturing an accessible interface for multiple,

single-function devices.

Decreasing costs are making E&IT devices more

affordable. Emerging markets have the greatest concentration of

low-income individuals, as well as a greater concentration of people

who are unable to read and write.

Increasing processing power, disk storage, memory

capacity, and battery life are enabling developers to integrate

advanced access technologies (speech recognition, text-to-speech

synthesis, projected displays, etc.) into devices where it has not

previously been technically possible to do so. In addition, the

Internet and the World Wide Web are now being utilized as a primary

infrastructure for education, government services, news, and business.

Customers’ technical knowledge and expectations are constantly

increasing, along with the use of wireless Internet appliances and

an increasing use of wireless infrastructures. Legal mandates to

manufacture more accessibly designed E&IT in support of people

with disabilities are also a major technological trend. In addition,

E&IT needs to be marketed to emerging markets in order for E&IT

manufacturers to increase sales and gain competitive price advantage

through economies of scale.

Economic Expansion

The strength of our global economy is, to a great

extent, the result of the investment in and application of new technologies

by governments, businesses, and individuals. Technology is the foundation

upon which developing countries can build thriving, financially

independent, self-sufficient economies. The technologies that build

this foundation include computers, networks, ATMs, wired and wireless

information infrastructures, wireless handheld Internet appliances,

and cellular telephones, to name a few. Applications include online

banking, distance learning, e-government, and e-commerce (World

Information Technology and Services Alliance, 2003).

Local Environment

Another force that drives the market for accessibly

designed E&IT is the local environment. Below is a discussion

of two environmental factors, variances in bandwidth and tourism.

Bandwidth

As of May 2004, more than half (51.39 percent) of

home Internet users in the United States relied on dial-up modems

of 56Kbps or less. Of all U.S. home Internet users, 42.53 percent

used 56Kbps modems, 6.52 percent used 28/33.3Kbps modems, and 2.34

percent used 14.4Kbps modems (Nielsen/NetRatings, 2004).

Computers using dial-up connections cannot handle

graphics as quickly and efficiently as computers connected via broadband.

It is for this reason that users surf the Internet with graphics

turned off. They do this to speed up downloads. In addition, low-bandwidth

connections do not lend themselves to a lot of graphic images, video-based

information, or streaming audio. Multimedia content can be problematic

for users with slower connections. Wireless devices communicating

with the Internet at slow connect speeds can also be a source of

accessibility and usability problems.

There are solutions to dealing with these problems.

Some companies have the ability to control the settings on the browsers

used on their employees’ personal computers (PCs). When available

corporate Intranet bandwidth is at a premium, these companies can

simply issue a central command to turn off graphics on all client

PC browsers. This can immediately free up as much as 80 percent

of available bandwidth. Designing Web sites for low-bandwidth access

tends to increase accessibility for users with disabilities. For

example, a graphics- or animation-intensive site often requires

high bandwidth and is inaccessible to those who are blind. In contrast,

a text-based site loads quickly and is accessible to screen readers.

Dial-up environments will continue to drive the development of more

accessible E&IT in the foreseeable future.

Tourism

During the first quarter of 2004, the United States

welcomed 8 million international visitors. This was an increase

of 12 percent compared with the first quarter of 2003.

Visiting tourists often make use of ATMs, self-service

kiosks, ticketing kiosks, and other tourism-related information

technologies. Many tourists only use English as a second language.

Developing content written in simplified English makes it more understandable

to users of ESL. In addition, using simplified English content has

other significant benefits, including the following:

• It reduces the cost of language translation.

• It reduces ambiguity.

• It speeds reading.

• It reduces liability associated with

misunderstandings.

The use of simplified content was originally included

in various accessibility design guidelines in support of people

with cognitive reading disabilities. Using simplified language has

now evolved into a market force driving the design of more accessible

E&IT.

Human Condition

Aside from forces stemming from the market and the

environment, many of the forces driving the accessible design of

E&IT fall under aspects of the human condition. E&IT products

must be designed with people of different disabilities, various

age groups, various levels of literacy, various languages, different

learning styles, and different experience levels with activities

such as using the Internet in mind. These aspects of the human condition

bring with them the demand for accessible E&IT products that

cater to not just one category, but to many different types of users.

Below is a summary of the forces that drive the demand for E&IT

that is accessible to a wide range of users.

Disability

Census 2000 counted 54 million people in the United

States with some type of long-lasting condition or disability (NCD,

2004). These individuals represented 19.3 percent of the 257.2 million

people who were age five and older in the civilian, noninstitutionalized

population. This is nearly one in five people. This includes a wide

range of disabilities, not all of which preclude the use of E&IT.

Within this population, Census 2000 found

• 9.3 million (3.6 percent) with a

sensory disability involving sight or hearing

• 21.2 million (8.2 percent) with a

condition limiting basic physical activities, such as walking,

climbing stairs, reaching, lifting, or carrying

• 12.4 million (4.8 percent) with a

physical, mental, or emotional condition causing difficulty in

learning, remembering, or concentrating

• 6.8 million (2.6 percent) with a

physical, mental, or emotional condition causing difficulty in

dressing, bathing, or getting around inside the home

• 18.2 million of those age 16 and

older with a condition that made it difficult to go outside the

home to shop or visit a doctor (8.6 percent of the 212.0 million

people this age)

• 21.3 million of those age 16 to 64

with a condition that affected their ability to work at a job

or business (11.9 percent of the 178.7 million people this age)

The design of E&IT products and services that

are accessible to people with disabilities appeals to the wider

population as well. Accessible design can significantly enhance

the sales of a product. For example, all of the following commonly

used products were first developed in support of people with disabilities

and are now used by the wider population:

• Auto-dialers

• Flatbed scanners

• Microphones

• Speech recognition

• Speech synthesis

• Talking ATMs

• Talking caller-ID

• Vibrating pagers

Age

Thirty-six million consumers 65 years of age and

older are living in the United States (Population, 2003). People

65+ years of age are often unable to see, hear, think, or move about

as easily as they did when they were younger. In order to enable

people 65+ years of age to access and use E&IT, these differences

must be accommodated. In addition, 52 percent of people 65+ years

of age have some type of disability. Thirty-three percent of persons

65+ years of age have a severe disability. By 2030, there will be

about 70 million older persons. People 65+ are expected to grow

to 20 percent of the population by 2030 (Administration on Aging,

2002). Furthermore, individuals who are accustomed to operating

IT will demand accessible IT as their functional capabilities diminish.

Language

Language is a driving force in today’s market

for more accessible E&IT. According to Global Reach, 262 million

English-speaking people are online. Non-English-speaking populations

online are 474 million. By the end of 2005, the ratio of English/non-English

speaking users will decrease significantly (Global Reach, 2003).

Sixty-four percent of people who visit the Internet

seek sites in languages other than English (Global Reach, 2003).

In a world where International Data Corporation (IDC) predicted

that Internet spending outside the United States would exceed $914

billion in 2003 (IDC, 2000), effective Web-site globalization is

the next imperative of Internet enterprises. Despite the vast international

opportunities projected, few U.S. companies appear poised to take

advantage of them. More than half (55 percent) of U.S. companies

do nothing to customize their Web sites for foreign visitors; less

than one-quarter even allow a choice of language, according to recent

IDC Internet Executive ePanel research. With such minor globalization

efforts, it is not surprising that 72 percent of U.S. companies

that are online currently draw 10 percent or less of their e-commerce

revenue from outside the United States. To increase their e-commerce

revenue, companies must strive to design Web sites that are accessible

to the non-English-speaking population.

Literacy

The Workforce Investment Act of 1998 defines literacy

as “an individual’s ability to read, write, speak in

English, compute, and solve problems at levels of proficiency necessary

to function on the job, in the family of the individual, and in

society.”

The International Adult Literacy Survey (Adult Literacy

Survey, 2003) was a 22-country initiative conducted between 1994

and 1998. In every country, nationally representative samples of

adults between the ages of 16 and 65 were interviewed and tested

at home using the same literacy test. The main purpose of the survey

was to find out how well adults use information to function in society.

Another aim was to investigate the factors that influence literacy

proficiency and to compare these factors among countries.

According to the National Institute for Literacy

(n.d.), “Very few adults in the U.S. are truly illiterate.

Rather, there are many adults with low literacy skills who lack

the foundation they need to find and keep decent jobs, support their

children’s education, and participate actively in civic life.”

According to the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), between

21 and 23 percent of the adult population, or approximately 44 million

people, scored at literacy proficiencies between 0 and 20 percent.

Another 25–28 percent of the adult population, or between

45 and 50 million people, scored at literacy proficiencies between

20 and 40 percent. Literacy experts believe that adults with skills

at these levels lack a sufficient foundation of basic skills to

function successfully in our society.

Many factors help to explain the relatively large

number of adults in the 0–20 percent category. Twenty-five

percent of adults in this category were immigrants who may have

just been learning to speak English. In addition, more than 60 percent

didn’t complete high school; more than 30 percent were over

the age of 65; more than 25 percent had physical or mental conditions

that kept them from fully participating in work, school, housework,

or other activities; and almost 20 percent had vision problems that

affected their ability to read print. A large percentage of the

population in the United States are at literacy proficiency less

than 40 percent. Design for individuals with limited literacy skills

also accommodates individuals who have learning disabilities or

cognitive disabilities that impact reading comprehension.

Learning Style

There are three major types of learning styles (Live

Text, 2000). They are visual, auditory, and kinesthetic (tactile).

Visual learners need to see a person’s body language and facial

expression to fully understand the content of what is being said.

They tend to prefer sitting at the front of a classroom, play, or

lecture hall to avoid visual obstructions (e.g., people’s

heads). They may think in pictures and learn best from visual displays,

including diagrams, illustrated textbooks, overhead transparencies,

videos, flipcharts, and handouts. During a lecture or classroom

discussion, visual learners often prefer to take detailed notes

to absorb the information.

Auditory learners learn best through verbal lectures,

discussions, talking things through, and listening to what others

have to say. Auditory learners interpret the underlying meanings

of speech through listening to tone of voice, pitch, speed, and

other nuances. Written information may have little meaning until

it is heard. These learners often benefit from reading text aloud

and using a tape recorder.

Tactile/kinesthetic learners learn best through a

hands-on approach, actively exploring the physical world around

them. They may find it hard to sit still for long periods and may

become distracted by their need for activity and exploration.

Enabling people to acquire information in the manner

most appropriate to their learning style(s) enhances the effectiveness

of E&IT and accommodates users with sensory disabilities.

Experience Level

Many people who are learning to use an application

on the Web for the first time want all the help they can get. There

will come a time, however, when the extra help is no longer needed

or desired. One of the benefits of accessible design practices is

having the ability to customize user interfaces based upon the wants,

needs, and preferences of individual users.

Legal Framework

Below is a summary of key laws, statutes, and standards

that have improved accessibility for individuals with disabilities

in this country. Each law is summarized, followed by a discussion

of who is primarily affected by the law and the approach toward

addressing accessibility issues that has been undertaken through

issuance of each law. These laws and standards are a driving force

in the market for accessibly designed products, as they set the

standards and guidelines for what must be done by the government

and industry to accommodate the needs of individuals with disabilities.

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires

that when federal agencies develop, procure, maintain, or use E&IT,

they must ensure that federal employees with disabilities have access

to and use of information that is comparable to the access and use

by federal employees who do not have disabilities unless an undue

burden (significant expenses or difficulties) is imposed on the

agency. The law also requires that individuals with disabilities

in the general public seeking information or services from a federal

agency have access to information and services comparable to that

provided to individuals without disabilities unless undue burden

is imposed on the agency. When compliance does impose an undue burden,

agencies must still provide disabled individuals with the information

and data by allowing them to use it by an alternative means of access

(e.g., captioning, audio description).

Section 508 covers E&IT such as computer hardware,

software, networks, ancillary equipment, firmware, technology services,

telecommunications products, information kiosks and transaction

machines, World Wide Web sites, multimedia, and office equipment

such as copiers and fax machines. Equipment that contains embedded

information technology used as an integral part of the product—but

the principal function of which is not the acquisition, storage,

manipulation, management, movement, control, display, switching,

interchange, transmission, or reception of data or information—is

not included under Section 508 (e.g., HVAC equipment and medical

equipment). As a guideline, E&IT systems can be considered to

be accessible to individuals with disabilities if they can be used

in a variety of ways that do not depend on a single sense or ability.

Section 508 has the potential to greatly improve

accessibility to E&IT for individuals with disabilities. The

Federal Government will likely become a better employer to the many

people with disabilities who work for it, as well as a model employer

for industry. In addition, members of the public with disabilities

will have greater accessibility to government information and services

related to technology.

Those affected directly by Section 508 include federal

departments and agencies and vendors who serve the Federal Government.

The initial impact is at the procurement stage. Section 508 must

be integrated into the procurement process by determining which

technical provisions from Section 508 apply in a given situation,

performing market research to determine the availability of products

and services that meet the applicable technical provisions, deciding

which technical provisions (if any) do not apply due to an exception,

and submitting technical specifications and minimum requirements

to a contracting officer.

Private companies and software developers are also

affected by Section 508. Although Section 508 does not require private

companies to alter their products, full implementation of the law

may provide an incentive for companies that want to do business

with the government to build better accessibility features into

their products. Currently, however, there is a perception by some

in industry that Section 508 conformance is being “rubber

stamped” by procurement officials and that the content of

documents describing Section 508 conformance, such as voluntary

product accessibility templates (VPATs), is not important as long

as it is merely offered. If Section 508 is fully addressed by procurement

officials, accessibility will become a key discriminator for federal

sales. Increased competition will raise the bar for hardware and

software vendors who want to create new and innovative solutions

to addressing accessibility issues. Software developers are impacted

by Section 508 in that they are now trying to integrate the applicable

Section 508 provisions into their entire software development life

cycle. Developers are faced with the challenge of either making

their software compatible with assistive technology or making software

products accessible without the aid of other AT.

In contrast to federal laws that take a push approach

toward improving the accessibility of E&IT by mandating that

new, better technologies are manufactured and adopted, Section 508

does not explicitly require the manufacturers to make their products

more accessible. Rather, Section 508 follows a pull approach, in

which the federal agencies are responsible for seeking better products

to address accessibility problems by procuring products that comply

with the provisions when such products are available in the commercial

marketplace or when such products are developed in response to government

solicitation.

Section 255 of the Telecommunications Act

Section 255 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996

requires telecommunications products and services to be accessible

to people with disabilities. This is required to the extent that

access is readily achievable. If manufacturers cannot make their

products more accessible, then they must design products to be compatible

with adaptive equipment used by people with disabilities when it

is readily achievable to do so.

Telecommunications products covered under this Act

include wired and wireless telecommunication devices, such as telephones,

pagers, and fax machines; products that have a telecommunication

service capability, such as computers with modems; and equipment

that carriers use to provide telecommunications services, which

includes the software integral to that equipment. Also included

are basic and special telecommunication services, including regular

telephone calls, call waiting, speed dialing, call forwarding, computer-provided

directory assistance, call monitoring, caller identification, call

tracing, repeat dialing, interactive voice response systems, and

voice mail.

The implementation of Section 255 of the Telecommunications

Act stands to improve access and the number and range of accessible

products in the telecommunications industry. Companies that manufacture

telecommunications products or provide telecommunications services

are expected to shift toward a more universal, inclusive design

process in the development of new products and services. Those affected

by Section 255 include manufacturers of telecommunications equipment

and customer premises equipment, as well as the providers of telecommunications

services. Companies must research ways to make their products more

accessible and provide training for their staff on accessibility.

Manufacturers must modify their design processes to ensure that

accessibility and usability are considered in the earliest design

phases of a product. The law has been beneficial to manufacturers

and service providers in that they have found that in making products

easier to use for people with disabilities, they often make them

easier to use for everyone.

The implementation of Section 255 takes more of a

push approach toward improving accessibility. The Act lays out a

set of guidelines that manufacturers must follow in designing new

products and services in this industry. Companies are advised to

use these guidelines and implement training procedures as specified

by the law. Section 255 is related to Section 508 of the Rehabilitation

Act in that the U.S. Access Board has incorporated the language

of the guidelines specified in Section 255 into the 508 standard.

Using consistent language has enabled companies to develop products

that meet both the design requirements for manufacturers and the

procurement requirements for federal agencies.

Hearing Aid Compatibility Act

The Hearing Aid Compatibility (HAC) Act of 1988 requires

that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ensure that all

telephones manufactured or imported for use in the United States

after August 1989, as well as all “essential” telephones,

are hearing aid compatible. “Essential” telephones have

been defined as coin-operated telephones, telephones provided for

emergency use, and other telephones frequently needed for use by

persons with hearing aids. This includes telephones in the workplace,

in confined settings like hospitals or nursing homes, and in hotel

or motel rooms.

Telephone manufacturers are directly affected in

that they must ensure that they design phones with volume control

and other features for those users with hearing aids. Owners of

hospitals, hotels, and other places with “essential”

telephones must ensure that they purchase telephones for their buildings

that are hearing aid compatible. Employers must ensure that all

telephones in both common and noncommon areas in their workplace

are hearing aid compatible and that any new telephones they purchase

are hearing aid compatible.

Unlike Section 255 of the Telecommunications Act,

under which companies must ensure that their products are accessible

to hearing aid users only if it is readily achievable for them to

do so, this requirement is absolute under the HAC Act. This law,

like Section 255 of the Telecommunications Act, takes a push approach

in mandating that corporations and business owners purchase telephones

that are hearing aid compatible and that the FCC ensures that all

essential telephones and telephones manufactured or imported for

use in the United States are hearing aid compatible.

Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990

recognizes and protects the civil rights of people with disabilities.

It provides protection from discrimination of individuals on the

basis of disability. Covered under ADA are a wide range of disabilities,

and a person with a disability is defined as anyone with a physical

or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major

life activities. These include physical conditions that affect mobility,

stamina, sight, hearing, and speech, as well as emotional illnesses

and learning disorders. ADA addresses access of individuals with

disabilities to the workplace (Title 1), state and local government

services (Title 2), and places of public accommodation and commercial

facilities (Title 3). In addition, phone companies are required

under ADA to provide telecommunications services for people who

have hearing or speech impairments (Title 4).

Title 1, which deals with employment of individuals

with disabilities, requires that employers do not discriminate against

qualified individuals with disabilities and that employers reasonably

accommodate the disabilities of qualified applicants and employees

by modifying work stations and equipment unless undue burden should

result in doing so. Title 2, which deals with public services, requires

that state and local governments do not discriminate based on disability

and that they ensure that their buildings are accessible, that new

and altered streets and pedestrian walkways contain curb cuts at

intersections, and that each service or program is operated so that

it is readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities.

In addition, this title requires that transit facilities, buses

and rail vehicles, key stations in rail systems, Amtrak stations,

and vehicles for demand response systems be made accessible unless

certain exceptions are met. Title 3, which deals with public accommodations,

requires that restaurants, hotels, theaters, shopping malls, retail

stores, museums, libraries, parks, private schools, and day care

centers, among other places of public accommodation, do not discriminate

based on disability. Any alterations to existing places of public

accommodation are required to be done in an accessible manner. In

addition, new busses for specified public transportation must be

accessible, and elevators must meet certain conditions. Title 4,

which covers telecommunications, states that telephone companies

must provide telecommunications relay services for hearing-impaired

and speech-impaired individuals 24 hours per day.

ADA has had a significant impact on American society,

allowing individuals with disabilities to pursue opportunities that

were not available to them in the past. One of the largest groups

affected by ADA are the employers of individuals with disabilities.

If an employer fails to comply with ADA, the employee can sue, forcing

the company to comply or pay damages. Thus, employers face the pressure

of ensuring that their workplaces are accessible and that they do

not discriminate against any qualified applicants on the basis of

disabilities. In addition, state and local government bodies, educational

institutions, and virtually all places of public accommodation or

employment are directly affected by ADA and must comply with the

regulations. The Annenberg Washington Program, a nonprofit institution

in communication studies, met in 1994 and expanded upon a previously

published White Paper in which it stated in its initial findings

that the average cost of most ADA accommodations is approximately

$36, a much lower amount than many anticipated. It found that the

impact of ADA on American businesses did not create onerous legal

burdens, as many believed would be the case, but rather has provided

a framework for employers and employees for dispute avoidance and

resolution. Overall, ADA has had a positive impact on society.

ADA has also taken a push approach toward addressing

issues of accessibility. The push is for the businesses and organizations

themselves to devise solutions based on the requirements set forth

in ADA.

Electronic Industries Alliance (EIA) Standards:

EIA-608 and EIA-708

The EIA-608 standard specifies the use of closed

captions in analog TV signals. EIA-608 arose to address the lack

of standards for Line 21 closed captioning, to ensure that new decoders

would all work the same way and that captioners could create captions

that would appear in a consistent and predictable manner on every

TV set. The Television Data Systems Committee of the EIA enhanced

the Line 21 system by adding new characters and assigning codes

that would allow the center of the screen to be used for captioning.

It also allowed roll-up captions, for the first time enabling real-time

captions to be placed somewhere other than the bottom of the screen.

This work became known as the EIA-608 standard, with which all captioning

software and all TV receivers built from July 1993 forward were

required to meet and comply.

When digital television (DTV) was developed, a new

need arose for the ability to change the size of the caption display—to

make the captions either larger and more readable or smaller and

less obtrusive. The conversion of closed captions for service with

digital was necessary. This need could not be accommodated in the

EIA-608 standard, and thus the EIA-708 standard was introduced.

The current version, EIA-708B, covers two areas. It defines how

captioned data is to be encoded and transmitted, known as the transmission

protocol or transmission layer. It also defines where in a DTV signal

the caption data are to be placed, the bandwidth allocated, and

the format of the data. The second area addressed is the display

protocol, which determines how captions are displayed on the screen

of a DTV. The 708 captioning format was designed to allow for the

use of the entire unicode set, which includes every character in

the alphabet in any language plus the complete range of symbols.

Almost any program can thus be captioned.

Many groups are affected by the introduction of the

EIA-708 standard. The Decoder Circuitry Act of 1990 stated that

“[d]igital television receivers and tuners must be capable

of decoding closed captioning information that is delivered pursuant

to the industry standard EIA-708-B.” This Act required the

FCC to update its rules for decoders as new technologies like DTV

developed. Television broadcasters are also largely affected by

the new 708 captioning format because the pressure is building to

produce new programming with digital closed captions based on this

standard. Broadcasters and producers must begin devising plans to

make this move and invest in the equipment they will need to do

so. Also very largely affected are the viewers with auditory impairments

who will benefit from much greater flexibility and a higher quality

of captioning with the EIA-708 standard.

A push approach toward the development of a new standard

was taken in the movement from EIA-608 to EIA-708 captioning. After

developing the new standard, the EIA has put the responsibility

on the broadcasters and producers to comply with these standards

in their captioning. This push to move from EIA-608 (analog) to

EIA-708 (digital) has brought many improvements to closed captioning.

Television viewers can now control the size of the caption text.

In addition, EIA-708 offers more letters and symbols, support for

multiple fonts and text and background colors, and allows for the

viewer to replace the traditional black box background with a colored

box or do away with it entirely. Also, EIA-708 increases the data

rate by 16 times over that allowed by EIA-608, permitting DTV captions

to contain much more information. However, most DTV content currently

still relies on the EIA-608 standard captions that have been converted

to the EIA-708 format because the consumer base of DTV receivers

is not high enough to justify the added expense of native EIA-708

encoding.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

was first enacted in 1975. The Act was passed to ensure that students

with disabilities receive free, appropriate public education and

the related services and support they need to achieve in the least-restricted

environment appropriate for their individual needs. IDEA was created

to help states and school districts meet requirements for educating

children with disabilities and to pay part of the expenses of doing

so. IDEA consists of three parts: Part B provides grants to states

for services for preschool and school-age children, Part C funds

early intervention services for infants and toddlers, and Part D

supports national activities to improve the education of children

with disabilities, including research and professional development

programs.

IDEA covers children with disabilities until they

graduate from high school or until they are 22 years of age if graduation

is delayed. Students who may fall under the Act are evaluated once

the possibility of a disability is raised. If it is determined that

the student does have a disability covered by IDEA, the school is

required to annually develop an individualized education program

(IEP) for the student, followed by placement in a regular classroom

setting when possible. Since its initiation, a set of amendments

made in 1997 has shifted the focus of IDEA from merely providing

children with disabilities access to an education to improving results

for all children in the education system.

The primary group affected and benefiting from IDEA

is children with disabilities. As a result of IDEA, students with

disabilities now learn among their peers. U.S. Senator Jim Jeffords

reports that since the initiation of IDEA, dropout rates for students

with disabilities have significantly gone down and graduation rates

have gone up. The percentage of college freshmen with disabilities

has tripled as a result of the improved education children with

disabilities have available to prepare them for college. Teachers

and parents of children with disabilities are also largely affected

by IDEA. These two groups play a large role in the development of

a child’s IEP. Teachers have also had to adjust to having

children with and without disabilities in the same classroom, learning

together. Others involved in the public education system, including

both state and local educators, are certainly affected as well.

The enactment of IDEA has followed a push approach

in requiring that public schools make a free education available

to students with disabilities that adheres to the provisions set

forth in the Act. The legislation places the responsibility upon

the schools and provides them with the requirements they must meet,

while providing some of the monetary means to do so.

Instructional Material Accessibility Act

The purpose of the Instructional Material Accessibility

Act (IMMA) of 2003 is to improve access to printed instructional

materials used by persons who are blind and other persons with print

disabilities in elementary and secondary schools. The Act accomplishes

this through the creation of an efficient system for the acquisition

and distribution of instructional materials in the form of electronic

files suitable for conversion into a variety of specialized formats.

The IMAA requires one national file format and a single national

repository for files, which simplifies the process of obtaining

materials for students with disabilities. Having a national file

format will make the conversion process for producing specialized

formats more efficient by reducing the amount of human intervention

necessary. Having one national file format will make it easier for

states, publishers, Braille software developers, and Braille transcribers

to work with files. Braille transcribers will have more time to

use their expertise in formatting and proofing files, leading to

high-quality Braille. Students will directly benefit because the

national file format will eliminate needless steps in scanning and

reformatting files. Teachers will benefit as well by having materials

available in specialized formats for their students who have disabilities

at the same time they are available to their other students. State

and local education agencies that receive federal funding under

the IDEA play a large role under the IMAA. They are responsible

for developing a statewide plan within two years of the enactment

of the IMAA to ensure that printed materials required for instructional

use in the classroom at elementary and secondary schools are available

in specialized formats to individuals with disabilities at the same

time they are made available to students without disabilities.

This Act is a push approach toward improving access

to printed instructional materials for visually impaired students.

The IMAA requires all the states to adopt the national file format.

Video Description Restoration Act

The Video Description Restoration Act (VDRA), currently

pending in Congress, would restore the FCC’s video description

rules, which were overturned in federal court on November 8, 2002.

The Act would guarantee TV access for individuals who are blind

or visually impaired through video description. The FCC would be

expressly granted authority to restore its minimum requirements,

with increased access over time. Those minimum requirements were

that the major networks and cable channels in the top 25 television

markets present at least four hours of described programming per

week, and that video-described programs be made available where

TV stations not in the top 25 markets have the equipment to do so.

The VDRA has been rigorously supported by the American Council for

the Blind, as well as other blind and deaf organizations because

they feel that in many ways video description is for people who

are blind what closed captioning is for individuals who are deaf.

The community of people who are blind or visually

impaired will benefit from the VDRA by once again having video description

available to them, which affords them the same access to information

on television as sighted viewers. Also affected would be the television

program providers and owners, who would be required to offer video

description for a portion of their programming. VDRA permits an

exemption if the provision of video description would be unduly

burdensome to the provider or owner, or if video description is

not necessary to achieve video programming accessibility by persons

who are blind or otherwise visually impaired.

The VDRA would restore the FCC’s rule for the

minimum requirements major networks and cable channels must meet

in terms of the amount of video description they provide. This push

approach taken by the FCC would ensure that at least a portion of

programs would be made available for the visually impaired through

video description. The number of hours of video description mandated

by the FCC may grow larger, leading to increased access to television

programming for the visually impaired over time.

Standards and Guidelines

In addition to the laws and statutes mentioned in

the previous section, additional standards and guidelines are driving

more accessibly designed E&IT. They are discussed below.

ADA Accessibility Guidelines

The Access Board’s guidelines issued under

ADA are to be completely updated and revised. The ADA Accessibility

Guidelines (ADAAG) cover the construction and alteration of facilities

in the private sector (places of public accommodation and commercial

facilities) and the public sector (state and local government facilities).

The accessibility guidelines issued under the Architectural Barriers

Act (ABA) primarily address facilities in the federal sector and

other facilities designed, built, altered, or leased with federal

funds. The guidelines under both laws are being updated together

in one rule that contains three parts: a scoping document for ADA

facilities, a scoping document for ABA facilities, and a common

set of technical criteria that the scoping documents will reference.

As a result, the requirements for both ADA and ABA facilities will

be made more consistent. The rule also includes new scoping and

technical provisions for accessible housing that derive from requirements

for “Type A” dwelling units contained in the 1998 edition

of the ICC/ANSI A117.1 standard, “Accessible and Usable Buildings

and Facilities.” Of specific interest is 4.34.5, Equipment

for Persons with Vision Impairments. Instructions and all information

for use must be made accessible to and independently usable by people

with vision impairments.

Telecommunications Act Accessibility Guidelines

On February 3, 1998, the Architectural and Transportation

Barriers Compliance Board (Access Board) issued its final guidelines

for the accessibility, usability, and compatibility of telecommunications

equipment and customer premises equipment covered by Section 255

of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (Telecommunications Act Accessibility

Guidelines, 1998). The Act requires manufacturers of telecommunications

equipment and customer premises equipment to ensure that the equipment

is designed, developed, and fabricated to be accessible to and usable

by individuals with disabilities, if readily achievable. When it

is not readily achievable to make the equipment accessible, the

Act requires manufacturers to ensure that the equipment is compatible

with existing peripheral devices or specialized customer premises

equipment commonly used by individuals with disabilities to achieve

access, if readily achievable.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0, 1999,

explain how to make Web content accessible to people with disabilities.

The guidelines are intended for all Web content developers (page

authors and site designers) and for developers of authoring tools.

The primary goal of these guidelines is to promote accessibility.

However, following them will also make Web content more available

to all users, no matter what user agent they are using (e.g., desktop

browser, voice browser, mobile phone, automobile-based personal

computer, etc.) or constraints they may be operating under (e.g.,

noisy surroundings, under- or over-illuminated rooms, in a hands-free

environment, etc.). Following these guidelines will also help people

find information on the Web more quickly. These guidelines do not

discourage content developers from using images, video, etc., but

rather explain how to make multimedia content more accessible to

a wide audience.

Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 1.0

The Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 1.0,

2000, provides specifications for Web authoring tool developers.