Aura

Full Name: Aura

Phase: Operating

Launch Date: July 15, 2004

Mission Project Home Page: http://aura.gsfc.nasa.gov/

Program(s): Earth Systematic Missions

NASA's Aura is a mission to understand and protect the air we breathe. With the launch of Aura NASA has begun to make the most comprehensive measurements of the Earth's atmosphere. It also caps off a 15-year international effort to establish the world's most comprehensive Earth Observing System, whose overarching goal is to determine the extent, causes, and regional consequences of global change. Aura's objective is to study the chemistry and dynamics of the Earth's atmosphere with emphasis on the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere (0-30km) by employing multiple instruments on a single satellite. The satellite's measurements enable scientists to investigate questions about ozone trends, air quality changes and their linkages to climate change. These observations provide accurate data for predictive models and provide useful information for local and national government agencies. Aura focuses on a number of science questions.

Is The Stratospheric Ozone Layer Recovering?

The stratospheric ozone layer shields life on Earth from harmful solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Research has clearly shown that excess exposure to UV radiation is harmful to agriculture and causes skin cancer and eye problems. Excess UV radiation may suppress the human immune system.

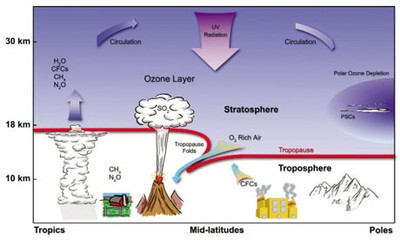

Ozone is formed naturally in the stratosphere through break-up of oxygen molecules (O2) by solar UV radiation. Individual oxygen atoms can combine with O2 molecules to form ozone molecules (O3). Ozone is destroyed when an ozone molecule combines with an oxygen atom to form two oxygen molecules, or through catalytic cycles involving hydrogen, nitrogen, chlorine or bromine containing species. The atmosphere maintains a natural balance between ozone formation and destruction.

The natural balance of chemicals in the stratosphere has changed, particularly due to the presence of man-made chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). CFCs are non-reactive and accumulate in the atmosphere. They are destroyed in the high stratosphere where they are no longer shielded from UV radiation by the ozone layer. Destruction of CFCs yields atomic chlorine, an efficient catalyst for ozone destruction. Other manmade gases such as nitrous oxide (N2O) and bromine compounds are broken down in the stratosphere and also participate in ozone destruction.

Satellite observations of the ozone layer began in the 1970s when the possibility of ozone depletion was just becoming an environmental concern. NASA's Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) and Stratospheric Aerosol and Gas Experiment (SAGE) have provided long-term records of ozone. In 1985, the British Antarctic Survey reported an unexpectedly deep ozone depletion over Antarctica. The annual occurrence of this depletion, popularly known as the ozone hole, alarmed scientists. Specially equipped high-altitude NASA aircraft established that the ozone hole was due to man-made chlorine. Data from the TOMS and SAGE satellites also showed smaller but significant ozone losses outside the Antarctic region. In 1987 an international agreement known as the Montreal Protocol restricted CFC production. In 1992, the Copenhagen amendments to the Montreal Protocol set a schedule to eliminate all production of CFCs.

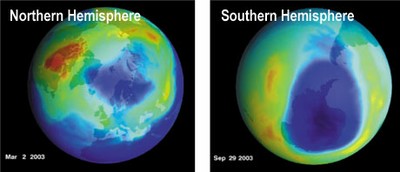

At both polar regions, climate and chemistry combine to deplete ozone during spring months. Dark blue indicates lowest ozone amounts. Arctic total ozone amounts seen by TOMS in March 2003 (above, left) were among the lowest ever observed in the northern hemisphere. The Antarctic ozone hole of 2003 (above, right) was the second largest ever observed.

Severe ozone depletion occurs in winter and spring over both polar regions. The polar stratosphere becomes very cold in winter because of the absence of sunlight and because strong winds isolate the polar air. Stratospheric temperatures fall below -88° C (-126.4° F). Polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) form at these low temperatures. The reservoir gases HCl and ClONO2 react on the surfaces of cloud particles and release chlorine.

Ground-based data have shown that CFC amounts in the troposphere are leveling off, while data from the Halogen Occultation Experiment (HALOE) on the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) have shown that amounts of HCl, a chlorine reservoir that is produced when CFCs are broken apart, are leveling off as well. Recent studies have shown that the rate of ozone depletion is also decreasing.

Recovery of the ozone layer may not be as simple as eliminating the manufacture of CFCs. Climate change will alter ozone recovery because greenhouse gas increases will cause the stratosphere to cool. This cooling may temporarily slow the recovery of the ozone layer in the polar regions, but will accelerate ozone recovery at low and middle latitudes.

What does Aura do?

The Aura instruments are designed to study tropospheric chemistry;

together Aura's instruments provide global monitoring of air pollution

on a daily basis. They measure five of the six EPA criteria pollutants

(all except lead). Aura provides data of suitable accuracy to improve

industrial emission inventories, and also to help distinguish between

industrial and natural sources. Because of Aura, we will be able to

improve air quality forecast models.

What Are The Processes Controlling Air Quality?

Agriculture and industrial activities have grown dramatically along with the human population. Consequently, in parts of the world, increased emissions of pollutants have significantly degraded air quality. Respiratory problems and even premature death due to air pollution occur in urban and some rural areas of both the industrialized and developing countries. Wide spread burning for agricultural purposes (biomass burning) and forest fires also contribute to poor air quality, particularly in the tropics. The list of culprits in the degradation of air quality includes tropospheric ozone, a toxic gas, and the chemicals that form ozone. These ozone precursors are nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, methane, and other hydrocarbons. Human activities such as biomass burning, inefficient coal combustion, other industrial activities, and vehicular traffic all produce ozone precursors.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified six criteria pollutants: carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, ozone, lead, and particulates (aerosols). Of these six pollutants, ozone has proved the most difficult to control. Ozone chemistry is complex, making it difficult to quantify the contributions to poor local air quality. Pollutant emission inventories needed for predicting air quality are uncertain by as much as 50%. Also uncertain is the amount of ozone that enters the troposphere from the stratosphere.

For local governments struggling to meet national air quality standards, knowing more about the sources and transport of air pollutants has become an important issue. Most pollution sources are local but satellite observations show that winds can carry pollutants for great distances, for example from the western and mid-western states to the East Coast of the United States, and sometimes even from one continent to another.