His Garden Grows

“My exercise focus is on gardening,” Arthur Canfield, 83, of Fairfax, Virginia, told us. “I hate the thought of exercise for exercise’s sake. I’ve never done that,” he said. “My exercise focus is on gardening,” Arthur Canfield, 83, of Fairfax, Virginia, told us. “I hate the thought of exercise for exercise’s sake. I’ve never done that,” he said.

Mr. Canfield grew up close to the soil. He remembers driving horses pulling hay, sometimes all day, and carrying water down to the garden on his uncle’s farm. His wife grew up in a family that made its living in the wholesale florist trade, so she, too, understood gardens.

Mr. Canfield and his wife brought their lifelong affinity for gardening with them into their marriage. When they settled in Fairfax, near Mr. Canfield’s job as an economist, the house they bought had about an acre of land, and they worked it — and worked it. “I didn’t want to be deskbound when I became a bureaucrat. That’s when I decided to become a serious gardener,” he said.

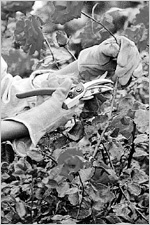

Gardening, Mr. Canfield told us, gives you an opportunity to exercise every part of your body and get satisfaction out of it at the same time. He said that gardening does more than build muscle and endurance. “You have to keep your balance. You’re reaching up to prune trees, bending over to check your tomato plants. The actual energy output at any given moment may not amount to much, but your whole system is participating the whole time,” he said. It adds up.

Mr. Canfield lives on his own and drives himself wherever he needs to go. He works in his garden 3 or 4 hours every day.

“It’s got to be fun,” he said. “I like to work what I do into a rhythmic pattern. Splitting wood, chopping down trees — the rhythmic pattern of exercise is like music. You’re absolutely a free spirit. You forget about it as you’re doing it.”

Mr. Canfield thinks that the idea of exercise sounds grim to most people — as though they have to do it, because there will be penalties if they don’t.

“But raking leaves is not something you should dread; it’s a joyous thing. In New England, it’s as much of an event as sugaring-off the maples; it’s the center of things for a while,” he said.

He wants to give other older adults the following message about increasing their physical activity: “Once they start, they’ll see that it builds on itself. It feels so good.” |

Most people know that exercise is good for them. Somehow, though, older adults have been left out of the picture — until recently. Today a new picture is emerging from research: Older people of different physical conditions have much to gain from exercise and from staying physically active. They also have much to lose if they become physically inactive.

Exercise isn’t just for older adults in the younger age range, who live independently and are able to go on brisk jogs, although this book is for them, too. Researchers have found that exercise and physical activity also can improve the health of people who are 90 or older, who are frail, or who have the diseases that seem to accompany aging. Staying physically active and exercising regularly can help prevent or delay some diseases and disabilities as people grow older. In some cases, it can improve health for older people who already have diseases and disabilities, if it’s done on a long-term, regular basis.

What Kinds of Activities Improve Health and Ability?

Four types of exercises help older adults gain health benefits:

Endurance exercises increase your breathing and heart rate. They improve the health of your heart, lungs, and circulatory system. Having more endurance not only helps keep you healthier; it can also improve your stamina for the tasks you need to do to live and do things on your own — climbing stairs and grocery shopping, for example. Endurance exercises also may delay or prevent many diseases associated with aging, such as diabetes, colon cancer, heart disease, stroke, and others, and reduce overall death and hospitalization rates.

Strength exercises build your muscles, but they do more than just make you stronger. They give you more strength to do things on your own. Even very small increases in muscle can make a big difference in ability, especially for frail people. Strength exercises also increase your metabolism, helping to keep your weight and blood sugar in check. That’s important because obesity and diabetes are major health problems for older adults. Studies suggest that strength exercises also may help prevent osteoporosis.

Balance exercises help prevent a common problem in older adults: falls. Falling is a major cause of broken hips and other injuries that often lead to disability and loss of independence. Some balance exercises build up your leg muscles; others require you to do simple activities like briefly standing on one leg.

Flexibility exercises help keep your body limber by stretching your muscles and the tissues that hold your body’s structures in place. Physical therapists and other health professionals recommend certain stretching exercises to help patients recover from injuries and to prevent injuries from happening in the first place. Flexibility also may play a part in preventing falls.

Which Ones Should I Do, and How Much Should I Do?

Some types of exercise improve just one area of health or ability. More often, though, an exercise has many different benefits.

In other words, exercise as much as you can. It’s best to increase both the types and amounts of exercises and physical activities you do. Gradually build up to include: endurance, strength, balance, and flexibility exercises. (We show you how in Chapter 4.)

Now that you have read about all the benefits of exercise, we hope you are enthusiastic about getting started. However, it’s important to start at a level you can manage and work your way up gradually.

For one thing, if you do too much too quickly, you can damage your muscles and tissues, and that can keep you on the sidelines. For another, your enthusiasm needs to last a lifetime. The benefits of exercise and physical activity come from making them a permanent habit. Start with one or two types of exercises that you can manage and that you really can fit into your schedule, then add more as you adjust to ensure that you will stick with it.

How much you exercise depends on you and on your unique situation. For some, muscle-building exercise might mean pushing more than a hundred pounds of weight at the local gym to keep your legs in shape for hiking or jogging. For others, it might mean lifting 1-pound weights to strengthen your arm muscles enough to use a washcloth. That might mean the dignity that comes from being able to wash yourself, instead of having someone else do it for you. The goal is to improve from wherever you are right now.

Some people are reluctant to start exercising because they are afraid it will be too strenuous. Researchers have found that you don’t have to do strenuous exercises to gain health benefits; moderate exercises are effective, too. (You will read more about the difference between vigorous and moderate exercises later in this book.)

How Much Physical Activity Is Enough?

Everyday physical activities can accomplish some of the same goals as exercise. But just how much should you do to get health benefits?

We can’t always give you answers, yet, but we can give examples of what researchers have found out. For instance, bus and taxi drivers, who are physically inactive, have a higher rate of heart disease than men in other occupations. And studies show that people who remain physically active have a lower death rate than people who don’t.

In another study, researchers measured muscle strength in 75-year-olds who regularly did tasks like housework and gardening and in 75-year-olds who were inactive. Five years later they found that the active people kept more of their strength than did the inactive people.

While we can’t yet tell you exactly how much everyday physical activity you should get to gain specific health benefits, the message of these studies is clear: Whatever your age, stay physically active!

In Chapter 4, we give you specific types and amounts of exercises to do. They can help you not only maintain your current levels of strength and fitness, but also help you build them up. Our examples also might encourage you to exercise muscles and joints that you have stopped using or that you use less often without even realizing it. |

Chapter Summary

Research suggests that growing older does not mean you have to lose your strength and ability to do everyday tasks and the things you enjoy doing. But an inactive lifestyle does mean that you probably will lose some of your strength and ability, and that you will be at higher risk for diseases and disabilities. Fortunately, even many frail people can improve their health and independence by increasing their physical activity.

Challenging exercises and physical activities done regularly can help many older adults improve their health, even when done at a moderate level. They may prevent or delay a variety of diseases and disabilities associated with aging.

Four types of exercises are important:

- Endurance activities increase heart rate and breathing for extended periods of time. They improve the health of the heart, lungs, and circulatory system, and help prevent or delay some diseases.

- Strength exercises make older adults strong enough to do the things they need to do and the things they like to do.

- Balance exercises help prevent falls, a major cause of disability in older adults.

- Stretching helps keep the body limber and flexible.

<< Back | Next >>