Testimony Statement by

Kerry Weems,

Acting Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

CMS

on

The Medicare Drug Benefit: Are Private Insurers Getting Good Discounts for the Taxpayer? before

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

U.S. House of Representatives

Thursday, July 24, 2008

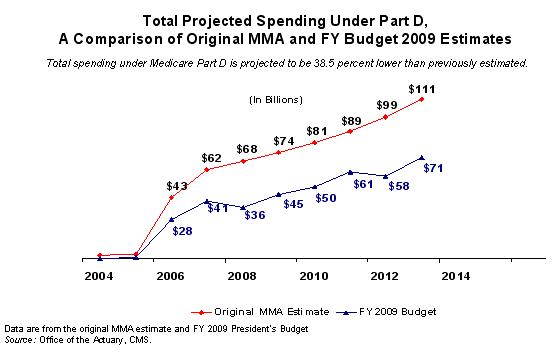

Good morning Chairman Waxman and distinguished members of the Committee. I am pleased to be here today to discuss the Medicare prescription drug benefit (Part D) and in particular, how we can ensure that people with Medicare continue to get the prescription drugs they need and the choices they have come to expect at the lowest possible price. The success to date of the Medicare prescription drug benefit provides strong evidence that competition among private plans has contributed significantly to lowering both government and beneficiary costs compared to what was originally estimated. Many Part D enrollees including “dual eligibles” – those entitled to Medicare as well as full Medicaid benefits – are experiencing added value through their Part D coverage in the form of effective, safety-promoting medication management programs. In my testimony today I will highlight the key successes to date of Medicare Part D, including taxpayer and beneficiary costs that are significantly lower than originally projected. I will also discuss some of the fundamental differences between Medicare Part D and the prescription drug coverage available through Medicaid, including the potential impact of applying Medicaid’s statutory drug rebate structure to all or a portion of the Part D benefit. Part D Successes More than 25 million beneficiaries have Part D prescription drug coverage in 2008 through a Prescription Drug Plan (PDP) or a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plan (MA-PD). Medicare beneficiaries are filling 100 million prescriptions a month under Part D. The program has been and continues to be a success on a variety of measures. Þ Lower than Projected Costs Experience with Part D thus far demonstrates that competition is working for beneficiaries and taxpayers alike. Part D has proven to be far less costly to the government than originally projected. According to the Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 President’s Budget, the net Medicare cost of Part D is almost 40 percent (about 38.5 percent or $243.7 billion) lower over the ten year period 2004-2013 compared to the original Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA) projection for that same period.

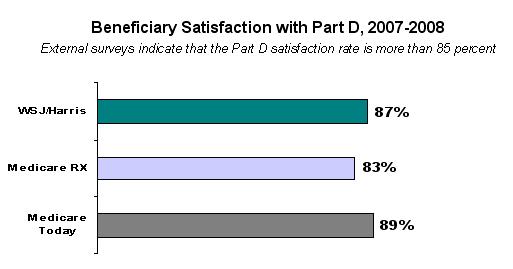

Roughly 29 percent (or 11.3 percentage points) of this decrease can be attributed to greater-than-expected effects of cost management, which is largely the result of competition. Beneficiaries also are reaping these savings. In 2008, the average monthly premium for available standard coverage is $25.1 While this is an increase over 2007 levels, when the average premium was $22, it is still about 40 percent lower than was originally estimated for 2008. Þ High Beneficiary Satisfaction Independent surveys have consistently shown that more than 85 percent of Medicare beneficiaries are satisfied with their Part D coverage. 2  Individuals like being able to choose a plan that best meets their unique health care needs. A single, one-size-fits-all drug plan would have limited the ability of beneficiaries to address their own health needs. Congress did create a defined “standard plan” with the MMA; however just 15 percent of enrollees have selected that defined standard benefit for 2008. Most beneficiaries opt instead for plans with lower premiums, no deductibles, and enhancements such as coverage for generics within the coverage gap. Enrollees are satisfied with the plans they are choosing. While Part D was already popular in its initial year with several independent surveys showing 75 percent or higher satisfaction rates, 3 follow-up surveys by Medicare Today in the fall of 2007 showed growth of more than 10 percent in satisfaction rates among beneficiaries, as compared with their satisfaction at the initial implementation of the benefit.4 In this same survey, 5 overwhelming majorities of enrollees gave Part D high ratings along a number of dimensions: 94 percent said the plan is convenient to use; 92 percent said they understand how the plan works; 91 percent said the plan has good customer service; and 86 percent said the co-pays are affordable. In addition, more than 9 out of 10 dual-eligible enrollees are satisfied with their coverage. 6 Þ Meaningful and Affordable Choices In 2008, beneficiaries have continued to have meaningful and affordable prescription drug plan choices that best meet their unique health care needs. More than 90 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in a stand-alone PDP had access to at least one plan in 2008 with premiums equal to or lower than what they paid in 2007.7 In addition, in every state, beneficiaries had access to at least one PDP with premiums of less than $20 a month, and a choice of at least five plans with premiums below $25 a month. The total number of zero deductible plans for 2008 increased from 2,933 in 2007 to 3,308. During open-enrollment, beneficiaries in any state could have selected a plan with coverage in the gap for generic drugs for under $50 a month.8 These high-value choices were offered without significant compromises to covered drugs: Part D sponsors’ 2008 formularies remain relatively unchanged in comparison to 2007 formularies. In fact, on average, sponsors’ 2008 formularies cover approximately 2 percent more distinct FDA-approved pharmaceuticals in comparison to 2007 formularies. Þ Unprecedented Beneficiary Support Information With a high value placed on beneficiary choice, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed or enhanced an unprecedented network of support to ensure people with Medicare and their loved ones have access to the information they need to select the plan that serves their health care needs best. Information is available online, in print, via toll-free phone support, or in-person through more than 900 partners across the country including State Health Insurance Assistance Programs, local Area Agencies on Aging, pharmacies, membership organizations, and countless other community partners. Beneficiaries have taken full advantage of these information centers. Throughout the 2008 open-enrollment period (November 15, 2007 – December 31, 2007), 1-800-MEDICARE received roughly 4.1 million calls.9 More than 3,000 customer service representatives were available in seven call centers across the United States to help people in English or Spanish. The web-based Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Finder, which offers beneficiaries comprehensive premium, pricing, benefit structure and quality information online, also has been a great success with beneficiaries. During the plan year 2008 open enrollment, the Plan Finder had more than 24 million page views. Even outside of open enrollment periods, the Plan Finder leads many other online tools available through www.medicare.gov, with a typical utilization level of 850,000 views per week. In contrast, other CMS websites like Nursing Home Compare receives 400,000 views per week and the participating physician directory receives 300,000 views per week. Þ Effective Price Negotiation At the time of enactment, Medicare analysts thought Part D plans would take several years to attain 25 percent reductions in drug prices compared to retail price levels from price discounts, manufacturer rebates, and utilization management. Those savings in fact occurred faster than originally forecast. CMS actuaries now estimate that Part D plans are achieving 29 percent savings off of Average Wholesale Price (AWP) through a combination of price discounts (22 percent) and rebates from manufacturers (7 percent). The average 22 percent discount has been corroborated by a CMS contractor, which found that the average discount off of AWP for certain Part D plans was 15 percent for brand-name products and 45 percent for generics. These price discounts are generally deeper than the average point of sale discounts in the Medicaid program. Moreover, prices for Part D-covered drugs have been stable. Since the beginning of 2007, CMS has been tracking price stability in Part D plans using a broad index. The number of unique drug products tracked ranges from 939 to 3,291 per plan. The results of the most recent submission from September 2007 indicate that the vast majority of enrollees (73 percent) were in plans where the price index did not increase more than 3 percent. In fact, 50 percent of enrollees were in plans where the price index did not increase more than 2 percent. Fourteen percent of enrollees were in plans where the price index actually decreased. Of course, all beneficiaries can also protect themselves under Part D from the impact of some changes in drug prices throughout the year by selecting a plan where cost-sharing is based on fixed co-payments rather than coinsurance for all preferred drugs. For 2008, 95 percent of enrollees (including LIS beneficiaries) have done exactly that. Þ Increased Generic Utilization The Part D benefit structure is helping to drive increases in generic utilization among beneficiaries, which is an important factor contributing to the lower cost of the program. The Part D generic dispensing rate for calendar year 2007 was 64.1 percent, up from roughly 60 percent for the third quarter of 2006. Greater use of generics helps beneficiaries achieve significant savings while also maintaining high quality care and reducing health care costs overall. Potential Impact of Importing Medicaid’s Rebate Structure into Part D Despite the overwhelming success and popularity of Medicare’s Part D benefit, some continue to look for ways to re-invent the wheel. When Congress enacted Part D, the decision was made to move dual eligibles to Part D, which offered a market-based approach to drug benefit structure and pricing. As noted previously, surveys show that more than 9 out of 10 dual-eligible enrollees are satisfied with their Part D coverage.10 The Administration opposed last year’s attempts to call upon the Federal government to negotiate and set the prices of Part D-covered drugs; we would be similarly concerned about suggestions that Medicaid’s drug pricing system should be imported to Medicare. This proposal is based on the same misconception that government price-setting can do a better job of satisfying beneficiaries and lowering prices than a competitive marketplace. Prescription drugs provided through fee-for-service Medicaid rely on a statutorily mandated rebate structure (drugs provided through Medicaid managed care plans do not receive these rebates). In order to have their products covered by the Medicaid program, drug manufacturers must enter into a rebate agreement with CMS. This rebate agreement requires pharmaceutical manufacturers to provide a rebate to the Federal and State governments for all drugs dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries. For brand name drugs, the rebate program requires a base rebate that is based on a statutorily-mandated discount equal to the greater of 15.1 percent of average manufacture price (AMP) or the difference between AMP and the best price given to any other plan or pharmacy benefit manager. An additional rebate is required if AMP increases faster than inflation. For generic drugs dispensed to beneficiaries, Medicaid receives a mandatory rebate of 11 percent of AMP. It is questionable whether applying Medicaid’s rebates to Medicare would result in better value for Part D enrollees. In a June 2005 paper, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) said that the average basic Medicaid rebate on brand drugs was 22 percent of AMP.11 This would make the rebate larger than a Part D plan’s liability in the catastrophic portion of the Part D benefit, and having a rebate larger than a plan’s liability could seriously distort the incentive in the Part D benefit structure for plans to manage costs in the catastrophic portion of the benefit. Given enrollee liability for drugs in the coverage gap, plans would have perverse incentives to manage costs only in the initial coverage period. Furthermore, simply comparing Medicaid’s rebates to Medicare does not capture all of the other efficiencies and savings achieved by Part D through encouraged use of generics and lower-cost drugs, cost-sharing opportunities for co-payments and coinsurance, and improved health care outcomes. Part D and fee-for-service Medicaid are inherently different structures with different purposes and different premises. Part D, like Medicaid managed care, places high value on beneficiary choice and variable formularies so that each individual can select from a wide range of plans and find the one best suited to his or her needs. Part D was designed to strike a balance between the need for an outpatient prescription drug benefit in Medicare and the difficult fiscal challenges presented by financing that benefit for the long-term. Part D was deliberately designed to complement rather than crowd-out existing employer and retiree private coverage. While focusing only on rebates at the exclusion of the core premises of Part D and other savings mechanisms may make a statutory rebate structure for Medicare seem appealing, such a structure could have far-reaching and significant impacts in both the Medicare program and the broader health care marketplace. The record from implementation of mandatory price controls and rebates in the Medicaid program reveals that these price-setting policies have the potential to disrupt the delivery of health care, increase costs in the private sector, 12 and discourage employers from continuing to provide prescription drug coverage at the levels they do today. The Congressional Research Service and Government Accountability Office (GAO) have each concluded that artificially forcing Medicare drug prices lower -- whether through direct price negotiation or a statutorily-set rebate system such as Medicaid -- could cause manufacturers to increase prices for other payers and consumers in order to offset revenue lost from Medicare.13 Furthermore, shortly after the Medicaid drug rebate program was first implemented, CBO examined its impact on other purchasers in the health care market and found that while access to rebates lowered Medicaid’s outpatient prescription drug expenditures, it may have also increased spending on prescription drugs by non-Medicaid purchasers.14 CBO also noted that Medicaid rebates could raise the launch prices of new pharmaceuticals. Additionally, GAO found that in the first two years of the Medicaid drug rebate program, the average best price for the outpatient drugs purchased by HMOs and Group Purchasing Organizations increased.15 CBO affirmed these findings again in 2005.16 As a result, the President’s Budget for the last two years has included proposals to eliminate “best price” from the Medicaid rebate calculation and create a revenue-neutral rebate to encourage drug manufacturers to offer competitive drug prices. Rather than moving the Medicaid rebate’s floor-setting structure to Medicare, the Administration has sought to make the Medicaid drug price structure more market-driven. With Medicare beneficiaries accounting for nearly 40 percent of prescription drug spending in the United States 17 (as compared to the 10-15 percent market share for Medicaid beneficiaries 18), it is not at all unreasonable to expect that a change from market-driven pricing in Part D to a statutory rebate structure like Medicaid’s could have an even stronger ripple effect on the cost of prescription drugs for other payers and consumers. If a combined total of more than 50 percent of the market became subject to a statutorily-dictated pricing structure, these two Federal programs could eliminate the potential for rebates to any other purchaser – including those who deliver health care benefits to working Americans, veterans, and to those who pay cash at retail for their prescription needs. This approach could also have negative consequences for Part D beneficiaries. It could lead to higher prices at the pharmacy, as manufacturers may respond by increasing prices to wholesale. These potential increases could be passed onto pharmacies and potentially beneficiaries at the point of sale. This is of particular importance to beneficiaries in the deductible and coverage gap portion of the Part D benefit. Other potential unintended impacts may compromise incentives to move enrollees toward low-cost therapeutic equivalent or generic drugs, or may undermine utilization management activities that plans use for important safety protections as well as cost control. Conclusion Based on a wide variety of metrics, the Part D program has been successful beyond expectations even in its infancy. Beneficiaries have meaningful choices for drug coverage at a cost that is much lower than originally estimated. CMS is concerned that efforts to adopt Medicaid’s rebate structure or any other form of government price-control for Medicare Part D would undermine these important successes and could have far-reaching impacts in the health care market beyond the Federal sector. Thank you again for the opportunity to speak with you today. I look forward to answering your questions.

1 These figures are calculated based on plan bid submissions and do not reflect beneficiaries’ actual enrollment choices.

2 Source: Wall Street Journal/Harris Poll (January 2008), Medicare Today Survey (October 2007), Medicare Rx Network (November 2007), CMS Internal Survey (January 2008).

3 Sources: (1) J.D. Power and Associates 2006 Medicare Part D Beneficiary Satisfaction Study, September 2006. (2) WSJ Online/Harris Interactive Health-Care Poll, conducted by Harris Interactive® between October 27 and 31, 2006 for The Wall Street Journal Online’s Health Industry Edition (www.wsj.com/health). (3) AHIP Survey: Tracking Seniors Who Self-Enrolled in the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit, September 2006. (4) Kaiser Family Foundation. Seniors’ Early Experiences with Their Medicare Drug Plans, June 2006.

4 Source: Seniors Impressions about Medicare Part Rx: Second Year Update, Medicare Today Survey, October 2007. http://www.medicaretoday.org/.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 HHS Press Release, HHS Announces More Than 90 Percent Of Medicare Beneficiaries Will Have Access To A Lower Premium Drug Plan in 2008, September 27, 2007.

8 Ibid.

9 Source: CMS Press Release, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefits Projected Costs Continue to Drop; Part D Attracts New Beneficiaries and Achieves High Rates of Satisfaction, January 31, 2008.

10 Source: Seniors Impressions about Medicare Part Rx: Second Year Update, Medicare Today Survey, October 2007. http://www.medicaretoday.org/.

11 Source: Congressional Budget Office:Prices for Brand-Name Drugs Under Selected Federal Programs, CBO Paper (June 2005), p. 19. http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=6481

12 Sources: (1) Congressional Budget Office: How the Medicaid Rebate on Prescription Drugs Affects Pricing in the Pharmaceutical Industry, CBO Paper (January 1996), http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/47xx/doc4750/1996Doc20.pdf. (2) Congressional Budget Office: The Rebate Medicaid Receives on Brand-Name Prescription Drugs, CBO Paper (June 2005).

13 Sources: (1) Congressional Budget Office: How the Medicaid Rebate on Prescription Drugs Affects Pricing in the Pharmaceutical Industry, CBO Paper (January 1996); (2) “Changes in Best Price for Outpatient Drugs Purchased by HMOs and Hospitals,” http://archive.gao.gov/t2pbat2/152225.pdf; and (3) Congressional Research Service, “Federal Drug Price Negotiation: Implications for Medicare Part D” http://www.law.fsu.edu/gpc2007/CongResServCRSRL33782_MedicarePrice%20Negotiation.pdf.

14 Congressional Budget Office: How the Medicaid Rebate on Prescription Drugs Affects Pricing in the Pharmaceutical Industry, CBO Paper (January 1996).

15 “Changes in Best Price for Outpatient Drugs Purchased by HMOs and Hospitals,” http://archive.gao.gov/t2pbat2/152225.pdf

16 Congressional Budget Office: The Rebate Medicaid Receives on Brand-Name Prescription Drugs, CBO Paper (June 2005).

17 Congressional Budget Office: Issues in Designing a Prescription Drug Benefit for Medicare, CBO Paper (October 2002), p. 11. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/39xx/doc3960/10-30-PrescriptionDrug.pdf

18 Congressional Budget Office: The Rebate Medicaid Receives on Brand-Name Prescription Drugs, CBO Paper (June 2005). Last revised: January 12,2009 |