Testimony Statement by

Richard S. Foster,

FSA, Chief Actuary

on

2008 Medicare Annual Report, Financial Portion before

Committtee on Ways and Means

Subcommittee on Health

U.S. House of Representatives

Tuesday, April 01, 2008

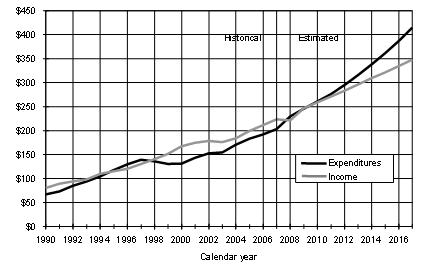

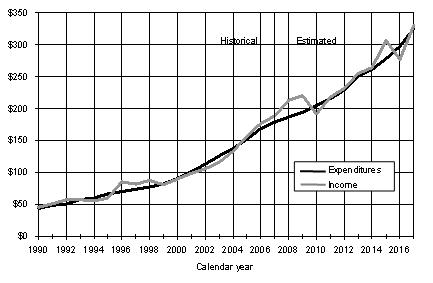

The Financial Outlook for MedicareChairman Stark, Representative Camp, distinguished Subcommittee members, thank you for inviting me to testify today about the financial outlook for the Medicare program as shown in the newly released 2008 annual report of the Medicare Board of Trustees. I welcome the opportunity to assist you in your efforts to ensure the future financial viability of the nation’s second largest social insurance program—one that is a critical factor in the income security of our aged and disabled populations. The financial outlook for the Medicare program, as shown in the new Trustees Report, is not markedly different from the findings in last year’s report. Overall, the outlook is slightly better, with actual costs in calendar year 2007 of $432 billion, an amount that was 1.5 percent lower than previously estimated. Most of this difference is attributable to slower growth in inpatient hospital expenditures than had been estimated. The financial status of the Medicare trust funds must be evaluated separately for each fund and for each account within the funds. I will first summarize the Trustees’ findings for the separate accounts and subsequently address the overall cost of Medicare and the “Medicare funding warning” that is triggered again this year. The Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund once again does not meet the Trustees’ formal test for short-range financial adequacy. The depletion of the HI trust fund is projected to occur early in 2019, the same year as was projected in last year’s Trustees Report. Beginning in 2008, HI dedicated revenues are projected to fall increasingly short of program expenditures, eventually covering less than one-third of estimated costs by the end of the Trustees’ 75-year projection period. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) created two separate accounts within the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund—one for Part B, which continues to cover the traditional SMI services, and one for the new Part D, which provides subsidized access to prescription drug coverage. Because of the annual redetermination of financing for both Parts B and D, each account will remain in financial balance indefinitely under current law. SMI costs, however, are projected to continue increasing at a faster rate than the national economy and beneficiaries’ incomes, raising concerns about the long-range affordability of scheduled financing. Background Over 44 million people were eligible for Medicare benefits in 2007. HI, or Part A of Medicare, provides partial protection against the costs of inpatient hospital services, skilled nursing care, post-institutional home health care, and hospice care. Part B of SMI covers most physician services, outpatient hospital care, home health care not covered by HI, and a variety of other medical services such as diagnostic tests, durable medical equipment, and so forth. SMI Part D provides subsidized access to prescription drug insurance coverage as well as additional drug premium and cost‑sharing subsidies for low‑income enrollees. A Part D subsidy is also payable to employers who provide qualifying drug coverage to their Medicare-eligible retirees. Only about 22 percent of Part A enrollees receive some reimbursable covered services in a given year, since hospital stays and related care tend to be infrequent events even for the aged and disabled. In contrast, the vast majority of enrollees incur reimbursable Part B costs because the covered services are more routine and the annual deductible was only $131 in 2007. Similarly, a large proportion of Part D enrollees have reimbursable prescription drug costs, given the common occurrence of prescriptions, the preponderance of zero-deductible plans, and the significant proportion of low-income enrollees, for whom the deductible does not apply. The HI and SMI components of Medicare are financed on totally different bases. HI costs are met primarily through a portion of the FICA and SECA payroll taxes.[1] Of the total FICA tax rate of 7.65 percent of covered earnings, payable by employees and employers, each, HI receives 1.45 percent. Self-employed workers pay the combined total of 2.90 percent. Following the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, HI taxes are paid on total earnings in covered employment, without limit. Other HI income includes a portion of the income taxes levied on Social Security benefits, interest income on invested assets, and other minor sources. SMI enrollees pay monthly premiums: $96.40 for the standard Part B premium in 2008 and an average premium level of about $25 for Part D standard coverage in 2008. For Part B, the monthly premiums cover a little more than 25 percent of program costs with the balance paid by general revenue of the Federal government and a small amount of interest income. Beginning in 2007, there is a higher “income-related” Part B premium for those individuals and couples whose modified adjusted gross incomes exceed specified thresholds. When the income-related premium is fully phased in (in 2009), beneficiaries exceeding the threshold will pay premiums covering 35, 50, 65, or 80 percent of the average program cost for aged beneficiaries, depending on their income level, compared to the standard premium covering 25 percent. Part D costs are met through monthly premiums, which are designed to cover 25.5 percent of the cost of the basic benefit for an individual, with the balance paid by Federal general revenues and certain State transfer payments. The Part A tax rate is specified in the Social Security Act and is not scheduled to change at any time in the future under present law. Thus, program financing cannot be modified to match variations in program costs except through new legislation. In contrast, the premiums and general revenue financing for both Parts B and D of SMI are reestablished each year to match estimated program costs for the following year. As a result, SMI income automatically matches expenditures without the need for legislative adjustments. Each component of Medicare has its own trust fund, with financial oversight provided by the Board of Trustees. My discussion of Medicare’s financial status is based on the actuarial projections contained in the Board’s 2008 report to Congress. Such projections are made under three alternative sets of economic and demographic assumptions, to illustrate the uncertainty and possible range of variation of future costs, and cover both a “short range” period (the next 10 years) and a “long range” period (the next 75 years). The projections are not intended as firm predictions of future costs, since this is clearly impossible; rather, they illustrate how the Medicare program would operate under a range of conditions that can reasonably be expected to occur. It is important to note that the results shown in this year’s report continue to be significantly more uncertain than those in past reports prior to enactment of the MMA. In particular, the Part D projections are estimated with only limited actual program experience. In addition, the Part B cost projections almost certainly understate the actual future cost of this component, due to the impact of the “sustainable growth rate” payment mechanism for physician services under current law. The projections shown in this testimony are based on the Trustees’ “intermediate” set of assumptions. Short-range financial outlook for Hospital Insurance Chart 1 shows HI expenditures versus income since 1990 and projections through 2017. For most of the program’s history, income and expenditures have been very close together, illustrating the pay-as-you-go nature of HI financing. The taxes collected each year have been roughly sufficient to cover that year’s costs. Surplus revenues are invested in special Treasury securities—in effect, lending the cash to the rest of the Federal government, to be repaid with interest at a specified future date or when needed to meet expenditures. During 1990-97, HI costs increased at a faster rate than HI income. Expenditures exceeded income by a total of $17.2 billion in 1995-97. The Medicare provisions in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 were designed to help address this situation. As indicated in chart 1, these changes—together with subsequent low general and medical inflation and increased efforts to address fraud and abuse in the Medicare program—resulted in a decline in Part A expenditures during 1998-2000 and trust fund surpluses totaling $61.8 billion over this period. (Part of this decrease was attributable to the shift of a substantial portion of home health care costs to Part B, which improved the financial status of the HI trust fund but did not reduce Medicare costs overall.) After 2000, Part A expenditures and income converged slightly, as the Balanced Budget Refinement Act and the Benefit Improvement and Protection Act increased Part A expenditures and the 2001 economic recession resulted in lower payroll tax income for Part A. Chart 1—HI expenditures and income (in billions)

Starting in 2004, the MMA increased Part A expenditures, through higher payments to rural hospitals and to private Medicare Advantage health plans. Moreover, the growth rate of expenditures is expected to continue to exceed growth in revenues.[2] Total HI income, including interest earnings, is expected to be less than expenditures in 2010 and all years thereafter. (HI dedicated revenues alone are estimated to fall short of total expenditures beginning this year.) Note that even relatively small changes in growth trends for either income or expenditures could have a very significant impact on the projected difference between these cash flows. In particular, the onset of deficits in the HI trust fund could occur somewhat earlier or later than this intermediate projection. Chart 1 also shows an upward shift in the level of HI expenditures from 2007 to 2008 and a temporary dip in income in 2008. These patterns are related, and they arise from the identification and correction of an accounting error. Specifically, a new, integrated accounting system for Medicare was phased in starting in 2005. This system inadvertently paid Part A hospice benefits from the Part B account of the SMI trust fund. As a result, Part A expenditures were too low in 2005-2007 (and Part B expenditures were too high, by the same amount). The problem was identified and corrected for future payments in September 2007, and the HI expenditures projected for 2008 and later reflect the full level of hospice benefits. The assets of the HI trust fund will be adjusted downward by approximately $12.6 billion in June 2008 to return the portfolio to the position in which it would have been if the hospice payment misallocation had not occurred. The adjustment is counted against HI income for 2008 in chart 1.

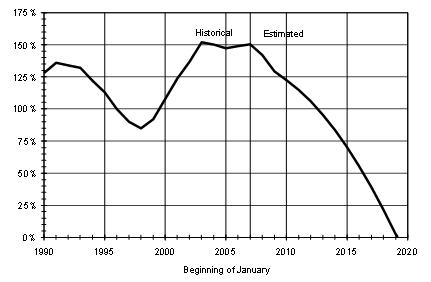

The Board of Trustees has recommended maintaining HI assets equal to at least one year’s expenditures as a contingency reserve. As indicated in chart 2, HI assets at the beginning of 2008 represented 142 percent of estimated expenditures for the year. Future asset growth, reflecting the diminishing difference between income and expenditures described above, is projected to be significantly slower than expenditure growth in 2008 and later. After 2010, as assets are drawn down to cover the annual deficits, the trust fund balance would decline and would be exhausted early in 2019 under the Trustees’ intermediate assumptions. Chart 2—HI trust fund assets (assets at beginning of year as percentage of annual expenditures)

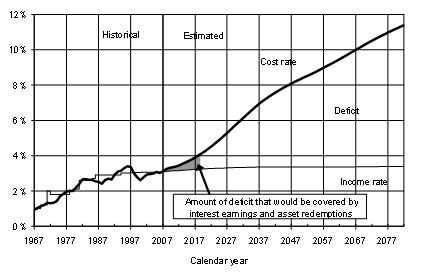

The projected exhaustion date for the HI trust fund is the same year as was projected in last year’s report but at an earlier point within the year, due to slightly lower projected payroll tax income and slightly higher projected benefits than previously estimated, together with the asset adjustment to compensate for the hospice cost misallocation. Long-range financial outlook for Hospital Insurance The interpretation of dollar amounts through time is very difficult over extremely long periods like the 75-year projection period used in the Trustees Report. For this reason, long-range tax income and expenditures are expressed as a percentage of the total amount of wages and self-employment income subject to the HI payroll tax (referred to as “taxable payroll”). The results are termed the “income rate” and “cost rate,” respectively. Projected long-range income and cost rates are shown in chart 3 for the HI program. Past income rates have generally followed program costs closely, rising in a step-wise fashion as the payroll tax rates were adjusted by Congress. Income rate growth in the future is minimal, due to the fixed tax rates specified in current law. Trust fund revenue from the taxation of Social Security benefits increases gradually, because the income thresholds specified in the Internal Revenue Code are not indexed. Over time, an increasing proportion of Social Security beneficiaries will incur income taxes on their benefit payments. Chart 3—Long-range HI income and costs under intermediate assumptions (as percentage of taxable payroll)

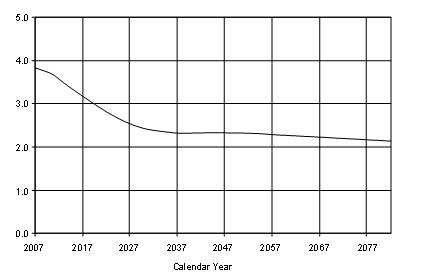

Past HI cost rates have generally increased over time but have periodically declined abruptly as the result of legislation to expand HI coverage to additional categories of workers, raise (or eliminate) the maximum taxable wage base, introduce new payment systems such as the inpatient prospective payment system, and make other changes. Cost rates decreased significantly in 1998-2000 as a result of the Balanced Budget Act provisions together with strong economic growth. After 2000, however, cost rates increased, partly because of the Balanced Budget Refinement Act and the Benefit Improvement and Protection Act. Cost rates are expected to continue increasing in 2008 and later and to accelerate significantly as the baby boom generation enrolls in Medicare, beginning in 2011. By the end of the 75-year period, scheduled tax income would cover only 30 percent of projected expenditures. The average value of the financing shortfall over the next 75 years—known as the actuarial deficit—is 3.54 percent of taxable payroll. For illustration, this deficit could be closed by an immediate increase of 1.77 percentage points in the HI payroll tax rate, payable by employees and employers, each. If, instead, no changes were made until the year of asset exhaustion, then the HI payroll tax rate would require an increase of about 2.23 percent (employees and employers, each). Note, however, that such changes would correct the deficit only “on average.” Initially, HI revenue would be significantly in excess of expenditures, but by the end of the period, only about one-half of the projected annual deficit would be eliminated. The long-range deficit could also be eliminated by many other approaches involving revenue increases and/or expenditure reductions, but its magnitude poses a very daunting challenge to policy makers. Per-person HI costs are expected to increase faster than per-worker tax revenues due to health care price inflation and increases in the utilization and intensity of services. Collectively, these factors generally exceed the growth in average earnings per worker, on which HI taxes are based. Important demographic factors contribute further to this growth differential. The effect of the baby boom generation on Medicare and Social Security is relatively well known, having been discussed by actuaries and others for the last 35 years. Basically, by the time the baby boom cohorts have enrolled in Medicare, there will be about 75 percent more HI beneficiaries than there are today, but the number of covered workers will have increased by only about 20 percent. When the HI program began, there were 4.5 workers in covered employment for every HI beneficiary. As shown in chart 4, this ratio was about 3.8 workers per beneficiary in 2007. When the baby boom joins Medicare, the number of beneficiaries will increase more rapidly than the labor force, resulting in a decline in this ratio to about 2.4 in 2030 and 2.1 by 2080 under the intermediate projections. Other things being equal, there would be a corresponding increase in HI costs as a percentage of taxable payroll. There are other demographic effects beyond those attributable to the varying number of births in past years. In particular, life expectancy has improved substantially in the U.S. over time and is projected to continue doing so. The average remaining life expectancy for 65-year-olds increased from 12.4 years in 1935 to 18.0 years currently, with an estimated further increase to about 22 years at the end of the long-range projection period. Medicare costs are sensitive to the age distribution of beneficiaries. Older persons incur substantially larger costs for medical care, on average, than do younger persons. Thus, as the beneficiaries age, over time they will move into higher-utilization age groups, thereby adding to the financial pressures on the Medicare program. Chart 4—Workers per HI beneficiary

Financial outlook for Supplementary Medical Insurance Part B The financial status of the SMI trust fund is very different than for HI, although rapid expenditure growth is a serious issue for both components of Medicare. The MMA established a separate account within the SMI trust fund to handle transactions for the new Medicare drug benefit. Because there is no authority to transfer assets between the new Part D account and the existing Part B account, it is necessary to evaluate each account’s financial adequacy separately. Chart 5 presents estimates of the short-range outlook for Part B. In contrast to the HI program, the income and expenditure curves for Part B remain closely related in the future. As noted previously, Part B premiums and general revenue income are reestablished annually to match expected program costs for the following year. Thus, the program will automatically be in financial balance, regardless of future program cost trends.[3] The income amount shown in chart 5 for 2008 includes a planned reimbursement of about $12.6 billion in recognition of the inadvertent charges made to the Part B account to cover the costs of certain Part A hospice benefit payments. As described previously, this cost misallocation occurred as a result of the introduction of a new accounting system, and the problem was corrected late in 2007 for future payments. The lump sum adjustment will repay the Part B account, with interest, for the inadvertent payments in 2005-2007. Chart 5—SMI Part B expenditures and income (in billions)

As shown in chart 5, Part B expenditures exceeded income during 1999-2004, resulting in account deficits over this period totaling $26.8 billion. These deficits resulted in part from greater-than-expected increases in physician, outpatient hospital, and certain other Part B costs. They also occurred due to a series of legislative acts that overrode scheduled reductions in Medicare physician fees after the financing rates had already been set for a year. In particular, the Consolidated Appropriations Resolution of 2003 (CAR) and the MMA raised Part B costs above the prior-law levels used to establish beneficiary premiums and general revenue financing. This pattern continued with the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA), the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (TRA), and the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Extension Act of 2007 (MMSEA). The resulting deficits in the Part B account drew down assets to a level that was well below the range needed for contingency purposes, as shown by the dotted lines in chart 6. Consequently, beneficiary premiums and matching general revenue financing were increased substantially for 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007.[4] These increases, together with the planned $12.6-billion asset adjustment in June 2008, restored Part B assets to an adequate level at the end of 2007—the first such occurrence since 2002.[5] Assets are estimated to increase further by the end of 2008 under current law. A somewhat lower (but still adequate) level would result in the likely event that legislation is enacted to override a scheduled 10.6-percent reduction in physician payment rates for the second half of 2008. Chart 6—Actuarial status of the Part B account in the SMI trust fund (assets minus liabilities as percentage of following year’s expenditures)

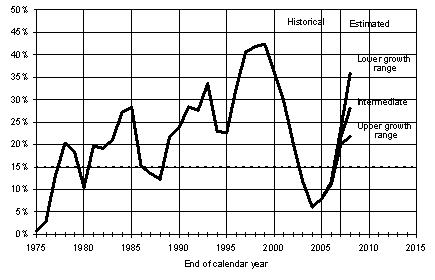

As suggested by the preceding discussion, the projected Part B expenditures shown in the 2008 Trustees Report are unrealistically low due to the structure of physician payments under current law. Future physician payment increases must be adjusted downward if cumulative past actual physician spending exceeds a statutory target. By the start of 2003, actual spending was already above the target level. The CAR, MMA, and DRA raised physician payments for 2004-2006 without raising the allowable target spending to match. The TRA raised the physician fee schedule update for 2007 and increased the target for 1 year, but specified that the 2008 physician fee update be computed as if the 2007 update had not been changed. Similarly, the 2007 MMSEA raised the physician fee schedule update for the first half of 2008, but the update for the second half will be computed as if the first 6 months of the year had not been changed. Together, these factors yield estimated reductions in physician payment rates of about 10.6 percent for July 2008, another 5 percent for January 2009, and an additional 5 percent for nearly every year during 2010-2016.[6] Because an aggregate 41-percent reduction in physician fees from current levels is implausible, the projected Part B expenditures shown in the 2008 Trustees Report must be considered substantially understated. By extension, costs shown for SMI, and for Medicare in total, are also understated. In the likely event that Congress continues to override the reductions in physician fees that would be required under current law, actual Part B costs could be roughly 10 to 20 percent higher than projected, and a greater increase in premium and general revenue financing would be required to match program costs and maintain assets at the necessary level. Financial outlook for Supplementary Medical Insurance Part D The MMA introduced the most significant changes to the program since its enactment in 1965. The new prescription drug benefit brings Medicare more in line with modern insurance coverage and medical practice while providing valuable new coverage for all beneficiaries who choose to enroll, especially those with low incomes. At the same time, of course, the new drug benefit adds substantially to the overall cost of Medicare. Beneficiaries obtain Part D drug coverage by voluntarily purchasing insurance policies from stand-alone prescription drug plans or through Medicare Advantage health plans. The costs of these plans are heavily subsidized by Medicare through a combination of direct premium subsidies and reinsurance payments. Medicare provides further support on behalf of low-income beneficiaries and a special subsidy to employers who provide qualifying drug coverage to their Medicare-eligible retirees. The financial risk associated with the private drug plans is shared between each plan and Medicare. Medicare’s cost for the various drug subsidies is financed primarily from general revenues. A declining portion of the costs associated with beneficiaries who also qualify for full Medicaid benefits is financed through special payments from State governments. Chart 7 shows actual Part D costs in 2004-2007 and estimates through 2016. For the Part D program, the financial operations in 2004 and 2005 related only to the prescription drug discount card and low‑income transitional assistance. The full Medicare prescription drug coverage became available in 2006. Part D income and outgo have been, and will continue to be, in virtually exact balance automatically due to (i) annual adjustments of premium and general revenue income to match costs, and (ii) a flexible appropriation process under which general revenues are appropriated to the trust fund account on a daily basis as needed to cover that day’s outlays. As a result of this latter feature, there is no need to maintain a contingency reserve in the Part D account.[7] Chart 7—SMI Part D expenditures and income under alternative assumptions (in billions)

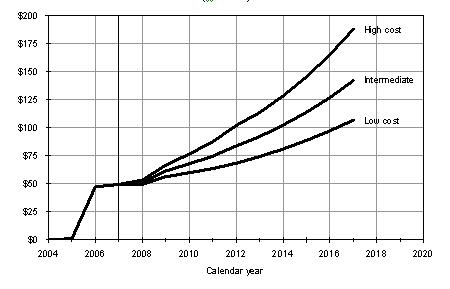

The Part D expenditure projections shown in the 2008 Trustees Report are significantly lower than those in the 2007 report and substantially lower than the original projections from 2003. The improvement relative to last year’s Trustees Report arises primarily from three factors. First, actual benefit costs in 2006 were lower than we (and the Part D plans) had estimated. In addition, the actual drug manufacturer rebates reduced Part D expenditures by 8.6 percent in 2006, significantly above the assumed level of about 5 percent. Finally, the projected cost growth trend for the next several years, which is based on our projected growth in prescription drug spending nationally, is somewhat lower than in last year’s report. Collectively, these effects reduce projected Part D spending in 2008-2017 by $129 billion or about 17 percent compared to last year’s report. The actual future cost of Part D remains uncertain, however, as illustrated by the projection range shown in chart 7, because only limited data are available to date on the actual operations and cost of the program. Long-range outlook for Supplementary Medical Insurance overall Chart 8 shows projected long-range SMI expenditures and premium income as a percentage of GDP. Under present law, Part B beneficiary premiums will continue to cover about 25 percent of total Part B costs, with the balance drawn from general revenues. Similarly, Part D beneficiary premiums are designed to cover 25.5 percent of the basic Part D benefit, on average. Because many enrollees qualify for the Part D low-income subsidy and do not have to pay full (or any) premiums, and because the low-income subsidy and retiree drug subsidy costs are not financed through premiums, total premium revenues currently represent about 9 percent of total Part D costs. The balance is paid by general revenues (77 percent) and State transfers (14 percent).[8] SMI expenditures are projected to increase at a significantly faster rate than GDP, for largely the same reasons underlying HI cost growth. For most of the past 15 years, prescription drug spending has been the fastest growing component of national health care costs. Consistent with that trend, the Medicare prescription drug spending under Part D is projected to initially grow faster than either Part A or Part B. Chart 8—SMI expenditures and premiums as a percentage of GDP

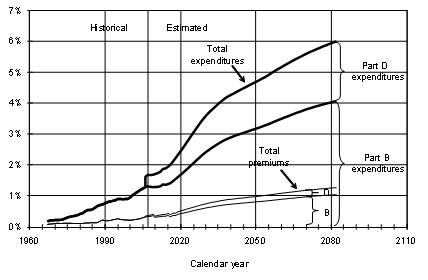

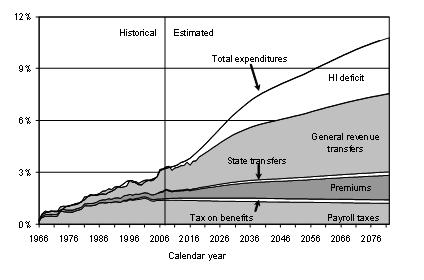

Although each SMI account is automatically in financial balance, the program’s continuing rapid growth in expenditures places an increasing burden on beneficiaries and the Federal budget. In 2010, for example, a representative beneficiary’s Part B and Part D premiums would require an estimated 11 percent of his or her Social Security benefit, and another 14 percent would be needed to cover average deductible and coinsurance expenditures for the year. By 2080, about 29 percent of a typical Social Security benefit would be needed to pay the Part B and Part D premiums, and about 37 percent would be required for copayment costs. Similarly, Part B and Part D general revenues in fiscal year 2010 are estimated to equal about 11 percent of the personal and corporate Federal income taxes that would be collected in that year, if such taxes are set at their long-term, past average level, relative to the national economy. Under the same assumption, projected Part B and Part D general revenue financing in 2080 would represent over 39 percent of total income taxes. Combined HI and SMI expenditures The financial status of the Medicare program is appropriately evaluated for each trust fund account separately, as summarized in the preceding sections. By law, each fund is a distinct financial entity, and the nature and sources of financing are very different between the two funds. This distinction, however, frequently causes greater attention to be paid to the HI trust fund—and especially its projected year of asset depletion—and less to SMI, which does not face the prospect of depletion. It is important to consider the total cost of the Medicare program and its overall sources of financing, as shown in chart 9. Interest income is excluded since, under present law, it would not be a significant part of program financing in the long range. Chart 9—Medicare expenditures and sources of income as a percentage of GDP

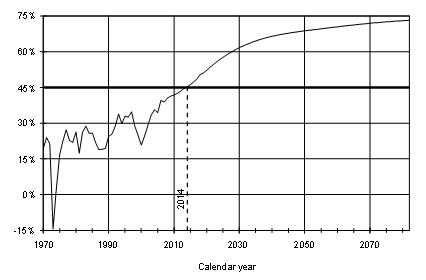

Combined HI and SMI expenditures are projected to increase from 3.2 percent of GDP in 2007 to 10.8 percent in 2082, based on the Trustees’ intermediate set of assumptions. The addition of Part D increased total Medicare costs by about 13 percent in 2006, and this increment is expected to ultimately grow to more than 20 percent. In past years, total income from HI payroll taxes, income taxes on Social Security benefits, HI and SMI beneficiary premiums, and SMI general revenues was very close to total expenditures. Beginning in 2008, overall expenditures are expected to exceed the aggregate amount of these non-interest financing sources, with the growing difference arising from the projected imbalance between HI tax income and expenditures. Throughout the long-range projection period, SMI revenues would continue to approximately match SMI expenditures. Over time, SMI premiums and general revenues would continue to grow rapidly, since, under current law, they would keep pace with SMI expenditure growth. HI payroll taxes are not projected to increase as a share of GDP, primarily because no further increases in the tax rates are scheduled under current law. Thus, as HI sources of revenue become increasingly inadequate to cover HI costs, SMI premiums and general revenues would represent a growing share of total Medicare income. Within the next 5 years, under current law, general revenues are expected to constitute the largest source of Medicare financing. Chart 10 shows the past and projected differences between Medicare’s total outlays and its “dedicated financing sources,” expressed as a percentage of total outlays. This ratio is estimated to reach 45 percent of outlays within the next 7 fiscal years.[9] As required under section 801 of the MMA, the Board of Trustees has issued a determination of “excess general revenue Medicare funding,” the third such determination. The corresponding determinations in the 2006 and 2007 reports triggered a “Medicare funding warning” last year. Section 802 of the MMA required the President to submit to Congress, within 15 days after the release of the FY 2009 Budget, proposed legislation to respond to the warning. Accordingly, the President submitted the proposed “Medicare Funding Warning Response Act of 2008” in February this year, and Congress must now consider it on an expedited basis. Because the difference is again projected to exceed 45 percent within the first 7 years in the 2008 annual report—specifically in 2014—a determination of projected “excess general revenue Medicare funding” is again issued, and another “Medicare funding warning” is thereby triggered. Chart 10—Projected difference between total Medicare outlays and dedicated financing sources, as a percentage of total outlays

Currently, most of the difference between Medicare expenditures and dedicated revenues is financed by the Part B and Part D general revenue transfers provided by law. The remainder of this difference equals the amount by which HI expenditures exceed HI tax income and premiums. This gap can be met initially by using a portion of the interest earnings on the assets of the HI trust fund and subsequently, through 2018, by redeeming the assets of the trust fund. The cash required for the payment of interest and the redemption of assets is drawn from the general fund of the Treasury. Over time, the difference between expenditures and revenues is projected to continue to increase under current law—reflecting not only further growth in statutory general revenue transfers to Medicare, as costs for Parts B and D continue to increase, but also the widening shortfall of HI tax income compared to expenditures. Although the statute labels the total difference as “general revenue Medicare funding,” it is important to note that there is no provision in current law to address the projected HI trust fund deficits once the fund’s assets are depleted. In particular, it would not be possible to transfer general revenues to HI to make up the difference. The comparison of expenditures versus dedicated revenues, as called for by section 801 of the MMA, is a useful measure of the magnitude of general revenue financing for Medicare plus the HI trust fund deficit. Similarly, the test underlying a “Medicare funding warning” can help call attention to the impact on the Federal Budget associated with the general revenue transfers to Medicare. The “Medicare funding warning,” however, should not be interpreted as an indication that trust fund financing is inadequate. That assessment can be made only by comparing each trust fund account’s expenditures with all sources of income provided under current law, including the statutory general fund transfers and interest payments. Conclusions In their 2008 report to Congress, the Board of Trustees emphasizes the continuing financial pressures facing Medicare and urges the nation’s policy makers to take steps to address these concerns. They also argue that consideration of further reforms should occur in the relatively near future, since the earlier that solutions are enacted, the more flexible and gradual they can be. Finally, the Trustees note that early action increases the time available for affected individuals and organizations—including health care providers, beneficiaries, and taxpayers—to adjust their expectations. I concur with the Trustees’ assessment and pledge the Office of the Actuary’s continuing assistance to the joint effort by the Administration and Congress to determine effective solutions to the financial challenges facing the Medicare program. I would be happy to answer any questions you might have on Medicare’s financial status.

[1]Federal Insurance Contributions Act and Self-Employment Contributions Act, respectively. [2] Health care costs, including those for Medicare, increase in proportion to the number of beneficiaries, the increase in the average price per service, the number of services performed (“utilization”), and the average complexity of services (“intensity”). In contrast, HI payroll tax revenues increase only as a function of the number of workers and the increase in average earnings. [3] The occasional odd patterns in the projected revenues occur when the normal January 3rd payment date for Social Security benefits falls on a Saturday, Sunday, or holiday. In such cases, payment is advanced to the next earlier business day—which is generally December 31st of the prior year. This situation will affect calendar-year Part B receipts in 2009-2010 and again in 2015-2016. [4] The increases were 13.4 percent, 17.4 percent, 13.2 percent, and 5.6 percent, respectively, for these 4 years. [5] The adequacy of the Part B contingency reserve is measured on an incurred basis. For this purpose, the June 2008 asset adjustment is treated as an “account receivable” item at the end of 2007 and is included in assets. In the absence of this factor, Part B assets would be at the lower end of the adequate range. [6] Following customary practice, the Medicare Trustees Report describes the average change in physician payment rates over specified periods. For example, it shows a decrease of about 10 percent for the second half of 2008 compared to the second half of 2007. Similarly, it indicates that the level for 2009 under current law would be 10 percent lower than the average level for 2008. These differences in average levels can be confused with the more commonly used physician update percentages described in the text above. [7] Individual Part D plans would normally maintain contingency reserves in case actual costs during the year exceed their expectations. [8] These percentages are estimates for 2008; the balance will shift somewhat over time as the State requirement declines from 90 percent to 75 percent of the forgone cost of prescription drugs for full dual beneficiaries and as the Part D national average bid and low-income subsidy benchmark demonstration programs are completed. [9]The dedicated financing sources are principally HI payroll taxes, the portion of income taxes on Social Security benefits that is allocated to the HI trust fund, beneficiary premiums, and the special State payments to Part D. These sources of dedicated revenues are depicted in the bottom four layers in chart 9. Last revised: January 12,2009 |