| Subject Areas |

|

History and Social Studies

|

| |

U.S. History - African-American |

| |

U.S. History - Civics and U.S. Government |

| |

U.S. History - Civil Rights |

| |

World History - Human Rights |

| |

| Time Required |

| | Three to four class periods

|

| |

| Skills |

| |

historical comprehension

historical interpretation

historical research

critical analysis of historical texts and images

critical thinking

production of a biographical profile

primary document analysis

Internet skills

|

| |

| Date Posted |

| | 4/12/2002 |

| |

| Feedback |

| |

Send us your thoughts about this lesson! |

| |

| Email this Lesson |

| |

Send this lesson to friends or colleagues |

| |

|

|

Who Was Cinque?

Introduction

This lesson plan focuses on Cinque, the

leader of the 1839 Amistad revolt, drawing on a variety of documentary

resources to examine how he was perceived by Americans on both

sides of the debate over slavery. Students first review the

facts of the Amistad revolt, including the legal proceedings

that ended in the Supreme Court decision that the Amistad captives

were free Africans, not slaves. Then, using newspaper reports

of the times, students examine how Cinque and his companions

were described by reporters, tracing the shifts in public opinion

that occurred on both sides as the case developed. Students

next look at visual representations of Cinque from those times,

noting how these images reflect the views of those who made

them as much as the physical reality of the man. Finally, students

attempt to lift away these layers of partisan perception by

examining transcripts of Cinque's testimony and letters written

by his companions, to see if they can arrive at an unmediated

view of this individual whom many now recognize as a hero. To

conclude the lesson, students produce their own portait of Cinque,

in a biographical profile or an editorial.

Learning Objectives

(1) To learn about the Amistad revolt

and its significance in the American debate over slavery;

(2) To trace shifts in public perception of the Amistad captives

and their leader as reflected in contemporary newspaper reports

and illustrations; (3) To examine court transcripts and letters

for direct evidence about the Amistad captives and their leader;

(4) To reflect on the process by which historians arrive at

an understanding about past individuals and events; (5) To

gain experience in working with newspaper reports, illustrations,

official documents, and other primary materials as resources

for historical study.

1

Introduce this lesson by reminding students of the story of

the Amistad revolt, which many of them may know from the Steven

Spielberg film, Amistad (1997). Ask those who have

seen the film to summarize the story, then draw on resources

available through EDSITEment to provide a fully accurate account.

- A detailed narrative of the Amistad

case, which traces events back to the Amistad captives'

life in Africa and includes contextual information about

the slave trade, is available at the Exploring

Amistad website, along with a timeline of events surrounding

the revolt and trial. (At the website's homepage, click

on "Discovery

Section" for a summary of the Amistad case with links

to the separate chapters of a more detailed narrative. At

the homepage, click on "Amistad

Timeline" for a chronology of events covering the period

from 1839 to 1846, with links to corresponding news reports.)

- More background on the Amistad revolt

is also available at the National

Archives Digital Classroom website homepage. Click on

"Primary Sources and Activities," then select "The

Amistad Case" for background and links to archival documents.)

- Discuss how students' knowledge about the Amistad revolt,

whether gained from the film or elsewhere, may differ from

the facts supplied by the historical record. Explain that

in this lesson they will discover that the facts about this

case, and the man at its center, have been in dispute from

the very start.

2

Use the resources available through

EDSITEment at the Exploring

Amistad website to provide students with examples of the

conflicting reports about Cinque, the leader of the Amistad

revolt, that appeared in various newspapers at the time. (To

access the website's newspaper archive from the homepage,

click "Library," then click "Newspapers"

and hit the "List All Newspaper Articles" button to browse

the collection.) The following are news reports that include

a description of Cinque during the period when he first came

to public attention:

- New

York Journal of Commerce, 30 August 1839: brief sympathetic

description of Cinque in custody aboard the brig Washington,

with comment on positive traits discerned in him "by physiognomy

and phrenology."

- Charleston

Courier, 5 September 1839: extended report on the U.

S. Navy's capture of the Amistad, with sympathetic descriptions

of Cinque and transcripts of two speeches he is supposed

to have made to his companions.

- New

York Morning Herald, 9 September 1839: report on "The

Case of the Captured Negroes" with demeaning descriptions

of Cinque and his companions.

- New

York Journal of Commerce, 10 September 1839: letter

from Lewis Tappan, a leading abolitionist and organizer

of the Amistad Committee, who reports on an interview with

Cinque conducted through a qualified interpreter.

- Charleston

Courier, 24 September 1839: brief account of Circuit

Court proceedings, with a sympathetic description of Cinque's

appearance at the trial.

- New

York Morning Herald, 4 October 1839: extended report

on "The Captured Africans of the Amistad," which ridicules

their abolitionist supporters and comments unsympathetically

on Cinque's character and behavior.

- Colored

American, 5 October 1839: response to critical reports

in other journals on the Amistad captives and their leader,

who is compared to Patrick Henry.

- Colored

American, 19 October 1839: extended essay on Cinque,

describing him as "the African hero."

3

Divide

the class into study groups and have each group read

and assess two or more contemporary newspaper accounts of

Cinque and his companions.

- Have students determine the point of view represented

in each article -- anti-slavery, anti-abolitionist, neutral,

etc.

- Have them mark in each article specific words and passages

that reveal the writer passing judgment on Cinque and thereby

prejudicing the reader's view of him, for better or worse.

- Have them note also the use of characterizations and comparisons

in each article that serve to categorize Cinque, whether

as "the son of a chief" or as "the ringleader" of the revolt.

- Have each group report its conclusions,

then work together as a class to describe the shifts of

public opinion toward Cinque recorded in these press reports.

Refer to the "Amistad

Timeline" available at the Exploring

Amistad website to gauge how legal developments may

have influenced public opinion. What different roles is

Cinque made to play by those who reported on the Amistad

case? How can historians choose among these versions of

Cinque to gain an understanding of him as he really was?

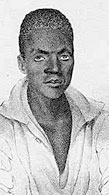

4 Turn next to images of Cinque, using the

resources available through EDSITEment to provide students with

a selection of the many drawings made of him during the height

of the Amistad controversy. The most comprehensive collection

of images can be found at the Exploring

Amistad website. (Click "Library" at the website's

homepage, then select "Gallery"

and click on the "List All Gallery Images" button to browse

the collection.) Included here are:

- Cinque

Addressing his Compatriots (1839): a lithograph published

soon after the Navy's capture of the Amistad, as a souvenir

of the event.

- Portrait

of Joseph Cinque (c. 1839): a color lithograph showing

the "leader of the gang" posed with his machete.

- The

Captured Africans of the Amistad (1839): a newspaper

cartoon showing Cinque and his companions diverting themselves

in prison.

- Phrenological

Developments of Joseph Cinquez (1840): illustration

taken from an article applying the then-accepted science

of phrenology to the task of assessing Cinque's character.

- Death

of Capt. Ferrer (1840): frontispiece of a pamphlet that

compiled news reports and court records of the Amistad case,

showing Cinque and his companions in the midst of their

revolt.

- Profile

of Cinque (1840): illustration from the same pamphlet

which accompanies a "biographical sketch" of Cinque and

is said to be based on casts made of his face while he was

imprisoned. (The illustration appears on page 8 of this

electronic text.)

Another important image of Cinque can

be found in the "African American Odyssey" exhibition at the

American

Memory Project website. (Click "Browse" at the website's

homepage, then select "African American Odyssey" and click on

the "Slavery" section of the exhibit; select "Part 2" and click

on "The

Amistad Mutiny," then scroll down to the image.)

The most celebrated image of Cinque is

an oil portrait made by Nathaniel Jocelyn in 1840; a contemporary

reproduction of this portrait can be found at the National

Portrait Gallery website. (Click on "Collections" at the

website's homepage and select "The

Amistad Case," then scroll down to the image.)

5

Provide each student group with a selection

of contrasting images for study. Have them first decide which

images correspond to the points of view they identified in their

study of newspaper reports. Are there additional points of view

reflected in any of the images?

- Next have students analyze each image to determine how

the artist has conveyed a particular point of view. Have

students consider the postures in which Cinque is portrayed

(e.g., arm raised in oration, holding a staff, standing

with arm akimbo, etc.); the clothing he wears (e.g., a breechcloth,

a toga-like robe, a scarlet shirt open at the neck, etc.);

the expression on his face (e.g., eyes seemingly closed

in sleep, gazing openly at the viewer, looking off to one

side, etc.); the settings in which he is placed (e.g., a

pastoral landscape, a ship's deck, a jailyard, etc.).

- Call attention also to the different media used for these

images: What kind of person appears in an oil portrait?

What kind of person appears in a newspaper cartoon? What

kind of person is presented as a scientific specimen?

- Have students consider as well the captions and texts

that accompany several of these images. How do they comment

on the picture? Are the writer's words always consistent

with the artist's point of view?

- Have each group offer a "reading" of two contrasting images

of Cinque in a class presentation, explaining the point

of view each offers on his actions as leader of the Amistad

revolt. Then discuss as a group whether the same man appears

in all these images. Compare, for example, the round-faced

Cinque in the pamphlet profile with the long-faced Cinque

who addresses his compatriots, or the youthful Cinque in

the Jocelyn portrait with the older-seeming "brave Congolese

Chief." How is it possible to tell from the evidence what

Cinque actually looked like? To what extent do all these

images show us instead what Americans at the time saw in

him?

6

Turn finally to what should be the most

unbiased evidence upon which to base a modern assessment of

Cinque's character and historic significance: transcripts

of court testimony and copies of personal letters. Such documents

can be found among the archives at the Exploring

Amistad website. Share with students:

- Deposition

by Cinque (7 October 1839): Cinque describes events

leading up to the revolt. (To retrieve this document, click

on "Library" at the website's homepage, then select "Newspapers";

click on the "List All Newspaper Articles" button and scroll

down to find the article titled, "A

New Movement," which reprints Cinque's deposition. Or

click "Search" on the website's homepage and type "A New

Movement" into the "Library Catalog" search engine.)

- Testimony

of Cinque (8 January

1840): Cinque describes his capture in Africa, his treatment

by slave-traders, and the Amistad's voyage to the time of

his arrest. (To retrieve this document, click on "Library"

at the website's homepage, then select "Court Records" and

click on the "List All Court Documents" button. Scroll down

to "Cinque's

District Court Testimony.")

- Letter

from Kale to John Quincy Adams (4 January 1841): One

of the Amistad captives urges Adams to win their freedom

before the Supreme Court. (To retrieve this document, click

on "Library" at the website's homepage, then select "Personal

Papers;" click on "letters written by the Africans to Adams,"

then scroll down and click "Kale

to Adams, January 4, 1841.")

- Letter

from Kinna to John Quincy Adams (4 January 1841): One

of the Amistad captives urges Adams to "talk hard" before

the Supreme Court and "make us free." (To retrieve this

document, click on "Library" at the website's homepage,

then select "Personal Papers;" click on "letters written

by the Africans to Adams," then scroll down and click "Kinna

to Adams, January 4, 1841.")

- Letter

from Cinque to the Amistad Committee (5 October 1841):

Cinque appeals for assistance to make the voyage back home.

(To retrieve this document, click on "Library" at the website's

homepage, then select "Personal Papers;" click on "letters

written by the Africans to Adams," then scroll down and

click "African

Repository in December 1841.")

7

Have students work with these documents

in their study groups. Ask them to compare these first-person

accounts of Cinque and his companions to those found in newspapers

at the time.

- Are there factual discrepancies between Cinque's description

of what happened and the journalists' reports? What differences

in emphasis are there between his version of events and

theirs? What differences in point of view? In the newspapers,

the Amistad revolt appears sometimes as a savage uprising,

sometimes as a noble crusade. How does Cinque characterize

their actions? What is the point of his story in his own

eyes? What role does he see for himself, and how does that

role compare to the roles assigned to him by his American

admirers and detractors?

- In their letters, Kale and Kinna respond directly to some

of the characterizations that had been made about the Amistad

captives. How do they see themselves? Call students' attention

to the "put yourself in our place" arguments used in both

letters. How do Kale and Kinna ask to be perceived by this

shift of perspective? What other arguments do they advance

to correct misperceptions about their people? How do these

arguments affect the views one might have formed based on

newspaper reports about the Amistad captives and their culture?

- Cinque's letter, like those of his companions, reflects

in its language the influence of his abolitionist supporters,

who sought to convert the Amistad captives to Christianity.

To what extent did the abolitionists affect the captives'

perceptions of their own experience by this teaching? Have

students mark in these letters the words and phrases that

seem to derive from the captives' course of Bible studies.

In what respects might one say that this language represents

a "veneer of Christianity"? In what respects might one say

that the abolitionists enriched the Amistad captives' perspective

on their own condition by sharing with them one of the core

texts of Western culture? Have students compare this religious

vocabulary with the competing vocabularies proposed by newspaper

writers who similarly sought to make meaning out of the

Amistad affair.

8 Conclude this lesson by having students

reflect in a class discussion on the difficulties of recovering

historic "truth" from documentary materials that offer several

versions of the truth to choose from. To what extent is it

the historian's responsibility to reduce such conflicting

points of view to a single set of facts? Have students explore

this issue firsthand by producing a report on Cinque based

on their research, answering the question "Who was he?" in

a biographical profile or editorial.

Extending the Lesson

Exploring

Amistad offers a wide range of lesson plans for helping

students learn more about this episode in American history.

They might investigate "The

Amistad as a Diplomatic Incident," examine "The

Amistad as Maritime History," explore "Abolition

and the Amistad Incident," or consider "A

Scientific Approach to the Amistad Incident." There are

also lesson plans that provide materials for staging "Amistad

Mock Trials" and for testing "The

Amistad as Campaign Issue." (Click on "Teaching" at the

website's homepage, then select "Curriculum" for links to

all these lesson plans.) Additional teaching ideas are available

at the Digital

Classroom website, which offers a chart that students

can use to sort out the many competing interests involved

in the Amistad legal battle. (Click on "Teaching with Documents" at the website's homepage, then select "Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)" and click on "The Amistad Case.")

Standards Alignment

View your state’s standards

|