|

||

|

||

|

|

Life in the Floating World: Ukiyo-e Prints and the Rise of the Merchant Class in Edo Period JapanIntroductionThe Edo Period (1603-1868) in Japan was a time of great change. The merchant class was growing in size, wealth, and power, and artists and craftsmen mobilized to answer the demands and desires of this growing segment of society. Much of the art of this period reflects both the tastes and the circumstances of this increasingly powerful class. Perhaps the most well known art form that gained popularity during this period was the woodblock print, which is often referred to as ukiyo-e prints, after one of the most common themes—the entertainment districts of Edo and Kyoto—presented in the medium. This lesson will help teachers and students to investigate Edo Period Japan through the window provided by these images of the landscape, life, and interests of the rising townspeople. Students will use the famous woodblock prints of artists such as Hiroshige (1797-1858) and Hokusai (1760-1849) as primary documents to help them gain insight on Japanese history. Guiding QuestionWhat do ukiyo-e prints tell us about Edo Period Japan? Learning ObjectivesAt the end of this lesson students will be able to:

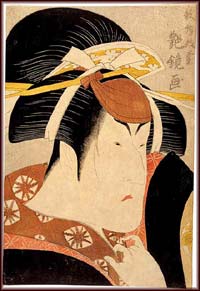

Preparing to Teach this LessonBackgroundThe Edo Period (1603-1868) in Japan is also known as the Tokugawa Period. It was during this period that the country was ruled by the Tokugawa shoguns who established the city of Edo (now called Tokyo) as their capital. The 250 year period during which the Tokugawa ruled was relatively peaceful, if secluded. After decades of interaction with merchants, travelers, and missionaries from around the world, the end of the sixteenth century saw the repression of the Christianity that had come with Portuguese and Spanish missionaries and stricter controls over European and other foreign traders in Japan. By 1635 foreigners were restricted to the port city of Nagasaki, and Japanese citizens residing outside of Japan were banned from returning. Four years later, almost all foreigners were forbidden from landing on Japanese soil. With the completion of several national seclusion edicts, Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate was almost closed to the world. It would remain so until the arrival of the American Admiral Matthew Perry in 1853. With the commencement of the Meiji Period in 1868, Japan opened up and interacted enthusiastically with other countries of the world. During the Edo Period the social hierarchy in Japan became segmented and Japanese society was divided into four categories or classes. At the top were the samurai warriors, who were the most respected because they supported their daimyo lords through loyalty and in battle. Most daimyo lords and samurai warriors received stipends from the government which enabled them to live, often without other means of support. The daimyo lords were required to leave their families as hostages in the capital city of Edo, under the watchful eye of the shogunate as they traveled to and from their domains, located in provinces throughout Japan. They were required to visit Edo once every three years. This was a major expedition for them, and kept them not only busy, but often drained their financial resources, leaving them with only limited funds for additional pursuits. The samurai warrior class also carried prohibitions on the accumulation of personal wealth, as well as other obligations to the shogun or military ruler. Farmers were ranked second because they produced food for the people. Tied to the land that they worked, farmers were not free to move about the country. Artisans were ranked third because they made goods or offered services used by the people in daily life activities. They lived and worked mostly in castle towns that were built by the daimyo lords and samurai warriors, and in the cities that developed. Merchants were considered to be at the bottom of society because they did not produce anything, but instead only traded in goods and money. In many ways, however, merchants were the class with the fewest restrictions on accumulating personal wealth. And, unlike farmers, merchants were able to move freely about the country, from town to town, in order to pursue their destinies. This social structure, with prohibitions and obligations for every class, created a system of checks on the power of all classes. This was particularly so of the merchant class, which had power from wealth but not from station, and the samurai warrior class, which had power from station but not from wealth. It was hoped that this social structure would prevent either of these classes from consolidating its power and amassing its fortunes for use in overthrowing the military shogunal ruler. One of the ways in which the merchant class attempted to assert itself was in the arena of the arts. While merchants were considered to be at the bottom of the social scale, their burgeoning wealth allowed them to patronize all types of arts, from theater to music to the visual arts. As the merchant class grew, greater numbers of people with larger disposable income made possible the support of entertainment such as Kabuki drama and Bunraku puppet theatre. In addition, people began to purchase small paintings and other kinds of visual art. In response to this patronage by the merchant class, many artists and artisans began to create works for the tastes and life experiences of members of that class. In addition, with a larger number of people able to purchase lower priced works the ability to create many pieces quickly became important and desirable. One medium in which this is most apparent is the ukiyo-e woodblock print which gained popularity during the Edo Period. The reproducibility of woodblock prints in which there may have been twenty, fifty or even hundreds of copies of an image, led to their being widely disseminated. The level of quality varied greatly. Some of the complex and rich prints were printed in short runs of fifteen or twenty, while some of the mass produced portraits of Kabuki actors were printed in enormous runs and sold as the ephemeral souvenirs of a night at the theater. In addition, their subject matter, which looked to life in the towns of Japan that were home to the merchant class, made the images extremely popular. The pictures are filled with the backdrop of town life, merchants’ homes, townspeople walking the streets under branches filled with peach blossoms or umbrellas blanketed with snow, as well as the roads that merchants often traveled in their work as traders. The word ukiyo-e means ”the floating world”, and is a euphemism coined to refer to the world of actors, geisha artist-entertainers, musicians, and wrestlers in Edo Japan. The term ukiyo-e is a pun in Japanese and the word can mean either the “sad world” or the “floating world.” Originally it was meant to refer to the sad aspects of life for members of this world who were outside of the formal social structure of four classes as described above. Not surprisingly, many of the ukiyo-e style prints are portraits of geisha artist-entertainers, however, images of the numerous forms of entertainment available to people living in cities and towns were also quite common. Portraits of Kabuki actors in full regalia, wrestling arenas, and musicians abound, as do images of the restaurants and tea houses where many town folk whiled away their evenings. Many also show scenes of daily life in Japan’s growing towns, while some of the medium’s most famous practitioners, such as Katsushika Hokusai used woodblock prints to infuse new life into the old tradition of landscape painting. Note: The word geisha is often mistakenly understood in English to mean prostitute. While there certainly were prostitutes in Tokugawa Japan, and there were geishas who had relationships with their clients, geishas were and are professional entertainers. Geishas train for thousands of hours over the course of their entire career in the traditional arts of Japan—such as playing the shamisan (the Japanese lute), flower arranging, the tea ceremony, and poetry composition. Geishas also continue to wear the elaborate costume of traditional Japan: the intricate hair styles, stunning makeup and multi-layered kimono which are so beautifully depicted in many ukiyo-e prints. You may wish to read about geisha in the exhibition Geisha: Beyond the Painted Smile at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, which can be reached through the EDSITEment reviewed web resource Asia Source . Background information on the class system during the Tokugawa period is available through the EDSITEment reviewed web resource Asia for Educators . Further information about the history and production of ukiyo-e woodblock prints , as well as the most common genres of ukiyo-e prints, can be found through the EDSITEment reviewed web resource The American Memory Project, Library of Congress . An excellent source on the historical background of the Edo Period is available at the EDSITEment reviewed web resource Asia for Educators . Information on this period can be reached by clicking on History to 1800, then Japan Teaching Units, and finally Tokugawa Japan. There you will find a link to an audio/video/text page which provides web video of scholars in the field of Japanese history discussing various aspects of the Edo Period. Transcripts of their discussions are also available on this web site, and will be used throughout this lesson. If your classroom is wired for the internet you may want to play these video clips in addition to having your class read the transcripts. Suggested Activities1. Japan and the Edo Period2. Tokugawa Society3. Picture Perfect: Make It Fast4. Picture Perfect: City Lights, City Life5. Picture Perfect: All the World is a Stage6. Picture Perfect: What a view!1. Japan and the Edo PeriodIn this activity students will be introduced to the history of the Tokugawa or Edo Period (1603-1868).

2. Tokugawa SocietyThe Tokugawa Period is exemplified not only by the political order and stability that arose during this period, but also a social order that was dictated and enforced by the shogunate.

Ask each group to present their answers to the rest of the class. Students should discuss the points where they have come to differing conclusions, and should use evidence from the texts to support their assertions. 3. Picture Perfect: Make It FastDuring the Tokugawa Period, woodblock prints that came to be known as ukiyo-e prints, gained in popularity. What, other than their beauty, contributed to the explosion in popularity of the ukiyo-e print in Tokugawa Japan? How did the social hierarchy of the period contribute to the popularity of the genre during the era? In this activity students will be able to gather information using our web-based interactive tool in order to build their own explanation of how the ukiyo-e print was influenced by the social structure of Tokugawa Japan, and how the prints are emblematic of the changes in society which typified the period. This activity is also provided here in PDF format.

4. Picture Perfect: City Lights, City LifeIn the next three activities students will look at some ukiyo-e prints and investigate the ways in which this art form reflected the lives and world of the merchant class that was the main audience for these works. All three of these sections can be found in the web based interactive, while the questions are all also available in PDF format. You may wish to lead your students through one, two or all three of these activities depending on the time constraints of your classroom. The structure of Tokugawa society was hierarchical, and also provided designated spaces in which each of the four social classes lived. The highest level of the shogunate rulers resided in Edo, while each daimyo lords alternated residence between Edo and his home prefecture. The samurai warriors were ideally meant to be in the service of their daimyo lords, and their assigned space overlapped with their master’s. Farmers were legally bound to their land and to the rural countryside. Artisans peopled the villages and cities which dotted the Japanese countryside, as did merchants. It was these growing urban spaces which became synonymous with the image of the merchant class during the Tokugawa period. This urban space and its population also became the often depicted subject and backdrop of numerous ukiyo-e prints.

5. Picture Perfect: All the World is a StageAs the name ukiyo-e suggests, many of the images created by artists such as Hiroshige and Hokusai are portraits of the people who populated ”the floating world”: the world of pleasure and entertainment. This world includes actors, musicians, geisha, wrestlers and others. As with the previous activity, students will be investigating the images of the floating world in the search for clues about what life was like in Tokugawa Japan.

6. Picture Perfect: What a view!Views of beautiful scenery and of the towns and villages that dot the Japanese countryside were also a very popular woodblock print genre. Many of the most popular images from this genre were printed as various series of views, such as Hokusai’s well known Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji. Often the guiding theme of these series possessed symbolic meaning. For example, Mt. Fuji, a dormant volcano which last erupted in 1707, is often thought of as symbolic of Japan itself. However, these prints also capture the views of daily life which would have been familiar to ukiyo-e audiences. Mt. Fuji, which is Japan’s tallest peak, was and is visible for many miles in every direction, and can be seen from Tokyo (Edo). It has been the subject of poetry and song, appearing in well known haikus and tankas. The mountain’s shifting seasonal view- its snow covered winters, its bluish summer silhouette- would have formed the daily backdrop for many of the people who enjoyed Hokusai’s artistic vision of the mountain. Other images, such the numerous series of scenes taken from the Tokkaido Highway by artists including Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Kuniyoshi, include views of the roads that were traveled by samurai warriors, farmers taking their crops to market, and the merchants who moved their goods around the country. For those who could afford it, travel for the sake of experience and religious pilgrimage became increasingly more common and more popular as the road system improved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

AssessmentAsk students to write a brief essay about the ways in which ukiyo-e prints provide a window into the lives of the merchant class in Edo Period Japan. How do these images reflect their experiences, tastes, pursuits and interests? Students should cite evidence for their assertions in the images themselves. They may want to begin the essay by reviewing their answers to the questions posed in Activities Four, Five and Six. Finally, students should investigate these images for their limitations. What don’t these images tell us? What sorts of scenes are not a typical part of these images? What people seem to be missing? Students may discover that, as much information as these images do provide, there is also a significant lack of information on the lives of women other than geisha artists—they do not address domestic life—where are the wives? Where are the children? They provide only rare views of farmers and samurai warriors. What do they say about the artisans who created the images? Ask students to incorporate into their essays an assessment of ukiyo-e prints: what information can these images provide, and what information is beyond their scope? Extending the LessonStudents can further enhance their knowledge of Ukiyo-e by looking at Japanese Woodblock Prints at the EDSITEment and Marco Polo partner site ArtsEdge.Selected EDSITEment Web Sites

Standards Alignment View your state’s standards |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||

| EDSITEment contains a variety of links to other websites and references to resources available through government, nonprofit, and commercial entities. These links and references are provided solely for informational purposes and the convenience of the user. Their inclusion does not constitute an endorsement. For more information, please click the Disclaimer icon. | ||

| Disclaimer | Conditions of Use | Privacy Policy Search

| Site

Map | Contact

Us | ||