|

Research shows that women exposed to DES in utero are at increased risk of developing clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA); of having structural differences in the anatomy of the reproductive tract; and of experiencing vaginal epithelial changes, fertility problems, and pregnancy complications. DES exposure does not appear to affect the menstrual cycle (Hornsby et al., 1994); however, structural changes in the müllerian tract may result in a decrease in menstrual flow (Cousins et al., 1980; Peress et al., 1982).

Even if a patient’s exposure to DES is unknown, a clinician may still suspect DES exposure based on physical findings observed at examination and illustrated in the figures included below. Women suspected of being exposed in utero need to be educated about DES exposure and to have their health monitored in the same manner as women known to have been exposed.

Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Vagina and Cervix

Women exposed to DES in utero experience an increased risk of developing CCA of the vagina and cervix. Among premenopausal women not exposed to DES, the risk of CCA is virtually nonexistent. However, the rate among premenopausal women exposed to DES in utero is approximately 1.5 in 1,000. Indeed, in a study population of 3,650 women exposed in utero to DES and 1,202 women not exposed, exposed women were 40 times more likely to develop CCA (Hatch et al., 1998).

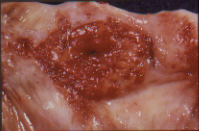

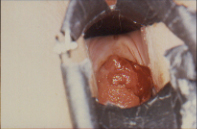

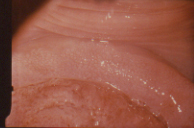

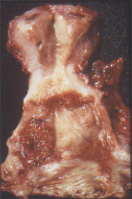

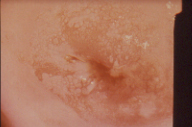

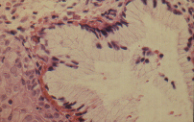

As of 2003, approximately 740 cases of CCA had been reported to the Registry for Research on Hormonal Transplacental Carcinogenesis from various parts of the world. Approximately two-thirds of these tumors were associated with intrauterine exposure to the nonsteroidal synthetic estrogen DES and, less frequently, to the chemically related synthetic estrogens dinestrol and hexestrol. (See DES Names for names of DES-type drugs that may have been prescribed to pregnant women.) Illustrations of these tumors are presented in figures 1, 2 & 3.

|

Figure 1 Clear cell adenocarcinoma arising in the distal third of the posterior wall of the vagina. The hypoplastic cervix is surrounded anteriorly by a hood and posteriorly by a rim. Details of a polypoid clear cell adenocarcinoma are seen [confined to the exocervix].

|

|

Figure 2 Close up picture of polypoid clear cell adenocarcinoma.

|

|

Figure 3 Clear cell adenocarcinoma confined to the exocervix.

|

Although most cases of CCA among women exposed to DES have been diagnosed when the women were in their late teens and early 20s, recent studies have shown that it is diagnosed in some women who are in their 30s, 40s, and 50s (Hatch et al., 1998; Herbst, 2000). The oldest confirmed DES daughter diagnosed with CCA is 51 years of age, and the oldest non-confirmed DES daughter is 52 years of age. There is no known upper age limit for developing CCA. It is not known whether these women will ever be risk-free because CCA in women not exposed to DES typically occurs during the postmenopausal years. All DES-exposed daughters need to be screened for CCA of the vagina and cervix throughout their lives, even when DES-related changes in the vaginal epithelium are absent.

Reproductive Tract Abnormalities

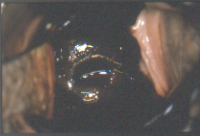

About one-third of DES-exposed daughters develop noncancerous changes in the vagina, and many develop changes in the cervix (Herbst et al., 1984; Jefferies et al., 1984; O’Brien et al., 1979; Robboy et al., 1979). Many of these changes are benign. However, some DES daughters experience reproductive problems as a result of an abnormality, such as a T-shaped uterus (Kaufman et al., 1977) or uterine constriction (Kaufman et al., 1986). The most common changes, including adenosis of the vagina and gross structural changes of the vagina and cervix, are illustrated in figure 4. Approximately one-fifth of women exposed to DES demonstrate these gross structural changes, such as a hooded (cockscomb) or rimmed cervix (Robboy et al., in press).

|

Figure 4 Colpo photograph of anterior cervical cockscomb covered with metaplastic squamous epithelium. A mosaic pattern is seen (M). The grape like structures on the lower portion of the cervix are composed of glandular epithelium. This is referred to as an ectropion (E).

|

|

Figure 5 Colpo photograph of anterior cervical collar covered with metaplastic squamous epithelium. This presents as a mosaic pattern (M). The ectropion (E) is partially replacing metaplastic squamous epithelium (white patches in lower portion of photograph). Similar changes in the vagina are collectively termed vaginal epithelial changes (VEC).

|

Adenosis requires treatment only in the unlikely event that it causes symptoms. Possible symptoms include mucoid vaginal discharge or postcoital vaginal bleeding. Some DES daughters have had both adenosis and CCA (Herbst, 1987). A progression from adenosis to cancer has not been documented and carefully followed in DES-exposed daughters, although such progression has been suspected in rare cases. Vaginal epithelial changes often disappear spontaneously without therapy. Structural changes of the vagina and cervix, such as those illustrated in figure 5, may also spontaneously disappear over time.

The uterine cavities of DES daughters may also be abnormal in size and shape. Kaufman and colleagues (Kaufman et al., 1980) found 69% of DES-exposed daughters had abnormal hysterosalpingograms (HSGs). The functional significance of this observation is unknown (Kaufman et al., 1977; Kaufman et al., 1984), and its generalizability is uncertain because those women who undergo HSGs usually do so as part of an infertility workup. However, women exhibiting these changes who do become pregnant have a greater likelihood of going into pre-term labor than DES exposed women whose HSGs appear normal (Kaufman et al., 1984).

Intraepithelial Dysplasia and Neoplasia

There is some evidence that women exposed to DES in utero are at greater risk of developing intraepithelial dysplasia and neoplasia of the vagina and cervix (Hatch et al., 2001; Robboy et al., 1984). In the most recent study, women exposed to DES in utero in comparison with women not exposed had a twofold increase of high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (Hatch et al., 2001).

Clinicians should plan treatment individually for each woman. Current data indicate that in many instances, low-grade squamous intraepithelial changes (e.g., human papilloma virus changes, mild dysplasia) may regress over time without treatment (Ostor, 1993). In the presence of a high-grade lesion (e.g., moderate or severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ), treatment is generally the same for DES-exposed individuals as for non–DES-exposed individuals. However, some evidence suggests that cryocautery used to treat DES-exposed women may result in cervical stenosis.

Infertility

The majority of women exposed to DES in utero have no problems conceiving or carrying a baby to term (Kaufman et al., 2000). Some DES daughters, however, have struggled with infertility.

Although some early studies on infertility did not find a link to DES exposure in utero (Barnes et al., 1980; Cousins, 1980), other studies did (Bibbo et al., 1977; Herbst et al., 1980). In fact, the most recent and comprehensive study found that DES-exposed women do have a higher risk of infertility than do unexposed women (Palmer et al., 2001). According to this study, 24% of DES daughters were unable to achieve a pregnancy versus 18% of women not exposed. DES exposure was most strongly associated with infertility due to uterine problems, with a relative risk of 7.7, and tubal problems, with a relative risk of 2.4. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies indicating that anatomic abnormalities in DES daughters may increase the risk of infertility.

When Kaufman and colleagues (Kaufman et al., 1986) examined the relationship of upper genital tract abnormalities and infertility in a sample of 367 DES exposed women who were actively trying to become pregnant, they found that the results of HSGs were abnormal in 73% of women who had difficulty conceiving for one or more years. The frequency of abnormal x ray films for women who conceived within one year was the same (74%). The percentage of women with normal x ray findings (37%) who had difficulty conceiving was similar to that of women with abnormal x ray findings (36%). The study concluded that the presence of abnormal findings on an HSG per se was not related to infertility.

|

Figure 6 T shaped appearance of the uterus with circular constriction noted around the proximal portion of the "horns" is noted. The lower portion of the uterus appears tapered and narrow.

|

However, when specific HSG abnormalities were related to infertility, the presence of a constriction of the upper uterine cavity was noted to result in a 2.26 times greater likelihood that a woman would not be able to conceive. If a T shaped uterus was found in association with such a constriction, the odds ratio for being unable to conceive was found to be 2.63 (Kaufman et al., 1986), see figure 6. These observations may help to explain possible causes for infertility in these DES exposed women, but no surgical or medical therapy is known to correct the typical T-shaped uterus.

The performance of HSG and endometrial biopsy procedures requires extreme caution in DES-exposed daughters because the distance between the fundus and the cervix may be shorter than in non-exposed women.

Poor Reproductive Performance and Pregnancy Complications

Several studies report poor reproductive performance in DES-exposed daughters with a range of 34% to 75% for successful pregnancy outcomes (Berger et al., 1980; Herbst et al., 1980; Kaufman et al., 1984; Ludmir et al., 1987; Mangan et al, 1982; Schmidt et al., 1980; Swan, 2000). Women exposed to DES in utero are at increased risk for pre-term labor, ectopic pregnancy, and first- and second-trimester spontaneous pregnancy losses (Kaufman et al., 2000). A woman exposed to DES in utero runs a three to five times greater risk of an ectopic pregnancy than a woman not exposed. Likewise, an exposed woman’s rate of miscarriage is estimated to be almost two to four times higher than that of a woman not exposed to DES in utero.

Problems during pregnancy are associated primarily with an increased risk for pre-term delivery. According to 3,373 pregnancy histories of exposed daughters and 1,036 pregnancy histories of unexposed daughters, approximately 20% of women exposed in utero to DES had pre-term births in comparison with only 8% of unexposed women (Kaufman et al., 2000). The largest and most definitive study to date found that 64% of women exposed to DES in utero delivered full-term infants in their first pregnancies (Kaufman et al., 2000). Overall, 75% of women exposed to DES in utero are able to deliver at least one healthy baby, as compared with 85% of women who were not exposed to DES in utero (Kaufman et al., 2000).

The rates for pre-term labor and delivery, rupture of membranes, and successful pregnancy outcome are similar to those reported by Mangan and colleagues (1982). The data suggest that once a pregnancy survives the first trimester, the chances of a successful outcome are good (92%). Durations of labor stages were similar to those reported by Thorp and colleagues (1990), but there was an increased risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Levine and Berkowitz (1993) postulated that this may be due to extremely vascular lower uterine segments and cervixes in DES exposed women. A number of DES-exposed women in their study had dangerously thin lower uterine segments at the time of primary cesarean section. They were subsequently counseled against a trial of labor with their next pregnancies.

Studies conducted since 1970 link genital tract abnormalities caused by in utero DES exposure to poor reproductive performance (Kaufman et al., 2000; Kaufman et al., 1984; Menczer et al., 1986; Palmer et al., 2001; Rosenfeld et al., 1980; Senekjian et al., 1988). Specific structural abnormalities produced within the müllerian system may cause the functional deficiencies of uterine contractility or cervical incompetence related to DES exposure. Kaufman and colleagues (2001) reported that women with upper genital tract lesions associated with DES exposure had worse reproductive outcomes than women with normal uterine anatomy. Goldstein (1978) reported cervical incompetence in patients with hypoplastic cervixes.

Ongoing research with DES daughters is addressing the effects of DES exposure on breast and cervical cancer risk, osteoporosis, and autoimmune diseases.

Breast and Cervical Cancers

In utero levels of estrogen may influence adult breast cancer risk. The high levels of estrogen to which DES daughters are likely to have been exposed in utero may place them at increased risk of developing breast cancer. In addition, having no children or having a first child at age 30 or older increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer; infertility or pregnancy problems may place some DES daughters in these groups at additional risk.

Preliminary findings suggest that exposure to DES in utero may confer an increased risk of breast cancer (Palmer et al., 2002). Though not statistically significant, the overall 40% excess risk in this study is higher than the estimate of 20% obtained in an earlier analysis of fewer cases (Hatch et al., 1998). Importantly, DES exposure was not associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer in women under age 40; however, exposure was associated with a more than twofold increase in breast cancer in women age 40 and older. In addition, DES exposure may be associated with tumors that are estrogen receptor-positive (Palmer et al., 2002). Continued investigation is imperative to confirm these findings.

At this time it does not appear that DES daughters are at increased risk for invasive cervical cancer (Hatch et al., 1998). The cohort is being followed for signs of dysplasia and invasive cancer.

Researchers will continue to monitor cohorts as they age to identify any increased breast and cervical cancer risks associated with DES exposure in utero.

Autoimmune and Other Disorders

Researchers are continuing to explore the possibility that DES exposure is related to an increased risk of autoimmune disease. Animal studies suggest an association (Blair, 1991), but the results of human studies are conflicting. Noller and colleagues (1988) found a higher rate of self-reported autoimmune disease among DES daughters than among women who had not been exposed to DES. However, researchers have been unable to find differences between DES daughters and unexposed women in the rates of any specific autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus.

Menopause

A recent study found that DES exposure was not related to premature ovarian failure or symptoms of menopause (Hornsby et al., 1995). Because the women queried were aged 37 to 39 at the time of the study, further research is necessary to determine if age at menopause is affected by DES exposure.

DES daughters need to receive regular gynecologic preventive examinations throughout their lifetimes. In addition, clinicians need to monitor all DES-related abnormalities for changes over time.

The following are questions to consider when screening DES daughters. These questions were developed by one of the Department of Health and Human Services’Centers for Excellence in Women’s Health online curriculum for nurses.

Questions for women pregnant between 1938 and 1971

- Did you have any difficulties (spotting, miscarriages) in any of your pregnancies?

- Did you take any medication of hormones during any of your pregnancies?

- Can you find out from your doctor or the hospital where you delivered whether you took any medication during your pregnancy?

Questions for men and women born between 1938 and 1971

- Did your mother have a history of miscarriages, spotting, or other difficulties with any of her pregnancies?

- To the best of your knowledge did your mother take any medications or hormones while she was pregnancy with you?

- Does your mother have diabetes?

- What is the name of the hospital and city in which you were born?

Additional questions for women born between 1938 and 1971

- Has a health practitioner ever told you about any vaginal or cervical changes seen or felt during a pelvic examination?

- Have you experienced: spotting or bleeding between menstrual periods? Unusual vaginal discharge or mucus color or consistency)

- Have you ever been pregnant?

- Any complications with the pregnancies?

- Have you ever had a miscarriage?

- Have you ever had a premature delivery?

- Have you ever had an ectopic pregnancy?

- Have you been unable to become pregnant after one year of unprotected intercourse with the same partner?

Additional questions for all patients who are considered DES exposed:

- Tell me about your feelings regarding your DES exposure?

- Describe how your DES exposure has affected your relationships?

- Would you like to discuss any concerns you have about your DES exposure?

- Have you discussed your exposure with your family?

- What are your concerns for your children?

- Would you like assistance in discussing this with your family?

When changes characteristic of DES exposure are present, the clinician may wish to consult a gynecologist familiar with the evaluation and follow-up of DES effects. (Please refer to DES Resources to find a gynecologist familiar with the effects of DES.)

Gynecologic Examination

The components of a gynecologic examination appropriate for a woman exposed to DES in utero include all those of a routine examination for any woman, plus special attention to those areas likely to have been affected by the exposure.

Clinical Breast Examination. Clinicians generally develop with each woman a breast cancer screening program based on her individual risks, use of oral contraceptives, and/or hormone replacement therapy. Vulvar Inspection. Changes in the vulva have not been associated with DES exposure. Vaginal and Cervical Inspection. The speculum inserted into the vagina should be large enough to permit easy visualization of the entire vagina and cervix. Warm water, not jelly, is preferable for lubrication during insertion of the speculum. Because excess mucus is sometimes present in the DES exposed woman, it may be necessary to remove it gently with a moist cotton swab. The clinician can then carefully inspect the epithelial surface of the vagina, rotating the speculum to visualize both the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Grossly, adenosis may appear red and granular, while squamous metaplasia may be indistinguishable from normal squamous epithelium. Cytology. To obtain specimens for a Papanicolaou smear from a DES-exposed daughter, the clinician thoroughly samples the epithelium in the upper third of the vagina with a wood or plastic spatula. Samples from the middle and lower third of the vagina are also appropriate if gross epithelial changes are evident there. The specimen should not come from vaginal secretions, however, because these secretions often contain an inflammatory exudate and degenerating epithelial cells. After rotating a spatula along the entire circumference of the vaginal fornixes, the clinician promptly transfers the vaginal material to a slide and fixes it immediately. The clinician then takes a second sample from the cervix—from the ectocervix—as well as the endocervical canal. A cytobrush is useful in sampling the endocervical canal, especially if the external os is small. If separate samples are taken from the ectocervix and endocervix, the material obtained from the ectocervical scrape is placed near the frosted end of the slide and fixed immediately. The specimen obtained with a cytobrush is then rolled out on the lower half of the same slide and immediately fixed. When the result of a Papanicolaou test is abnormal, the clinician needs to consult with a gynecologist experienced in evaluating DES exposed daughters. (Please refer to DES Resources.) Colposcopy. The chief benefits of colposcopy are that it permits an accurate assessment of the extent of vaginal and cervical epithelial changes, and it is useful as an aid to detect those areas most likely to disclose abnormalities on biopsy. Colposcopy has not proved to be an essential tool in detecting CCA. This is partly because specific vascular changes are absent in CCA and partly because some tumors may be confined to an intramural location in the vagina and cervix. If colposcopy is to be done, it should be performed before iodine staining. Iodine Staining. The clinician may decide that iodine staining of the vagina and cervix is necessary to confirm the boundaries of epithelial changes observed by colposcopy or to determine the boundaries when there has been no colposcopy (figures 7a, 7b & 8). Lugol’s solution at half strength (2.5% iodine with 5% potassium iodide in water) is suggested. Because the iodine stains only the mature squamous epithelium lining the vagina and cervix, this technique is not reliable for detecting lesions within the vaginal or cervical wall. To properly assess the tissues after staining, the clinician rotates the speculum while withdrawing it. After inspection, it will be necessary to reinsert the speculum if a biopsy is necessary. Lubrication with jelly to compensate for the dehydrating effect of the iodine facilitates insertion.

|

Figure 7a Normal cervix in a DES exposed woman as viewed through a colposcope. After application of acetic acid, the normal squamous epithelium is pink.

|

|

Figure 7b After application of an iodine solution, the entire surface of the ectocervix is brown due to the high glycogen content of the normal squamous epithelium.

|

|

Figure 8 After iodine staining, the entire cervix and part of the vagina failed to stain (pale yellow) and are distinct from those areas of normal (glycogenated) squamous epithelium in the vagina, which are stained brown.

|

Vaginal and Cervical Palpation. A crucial part of the DES examination, palpation may provide the only evidence of CCA, especially on the rare occasion when it lies beneath the mucosa. It is important to carefully assess the entire length of the vagina, including the fornixes. During palpation, vaginal ridges and structural changes of the cervix may be evident. Areas of thickening or induration should raise suspicion and should lead to sampling by biopsy. Tissue Biopsy of Atypical Findings. Biopsies are necessary whenever the vagina or cervix is indurated or granular, contains a palpable nodule or larger mass, or has discrete areas that appear to be of a different color or texture than the surrounding tissue. Highly atypical colposcopic findings also warrant biopsy (figures 9, 10a, 10b & 11). Random sampling of non-staining areas of the vagina or the cervix is not advised, as these areas rarely disclose neoplastic or preneoplastic changes. Ferrous sulfate (Monsel’s solution) or a silver nitrate stick may occasionally be required to stop bleeding after a biopsy.

|

Figure 9 Polypoid clear cell adenocarcinoma (C) bordered by dark zone of adenosis (A) lies on the anterior vaginal wall. The vaginal adenosis and the extensive ectropion (E) of the cervix appear red in the fresh state.

|

|

Figure 10a Colpo photograph of outer cervix and vaginal fornix; the latter demonstrates an area of white epithelium.

|

|

Figure 10b After application of Lugol's iodine solution, the white epithelium is evident as an area that did not take up the stain.

|

|

Figure 11 Mosaic pattern demonstrates metaplastic squamous epithelium on biopsy. These similar colposcopic patterns are seen in DES exposed individuals and usually demonstrate only squamous metaplasia on biopsy.

|

Bimanual Examination. The bimanual examination should include examination of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries with the fingers of one hand while the other hand presses on the abdomen. It should also include examination of the vagina and rectum performed in a routine manner.

Examination Schedule

The appropriate interval for follow-up examination of DES-exposed daughters is determined on an individual basis. For most patients with non-staining epithelial or structural changes (figures 6 & 7) in the vagina or cervix, or with microscopic changes such as adenosis (figures 14a & 14b), yearly examinations are adequate. Before a diagnosis of intraepithelial neoplasia can be confirmed, all abnormal cytologic and biopsy specimens should be reviewed by a pathologist who is thoroughly familiar with changes in samples from DES exposed women, particularly because immature squamous metaplasia is often difficult to distinguish from intraepithelial neoplasia.

|

Figure 14a Grossly red area in the vagina contains adenosis.

|

|

Figure 14b An endocervical gland structure is noted within the lamina propria of the vagina.

|

Important steps in the follow-up examination include palpation, inspection, and cytologic tests. Attention should focus on the changes observed since the initial evaluation. Cervical and vaginal cytologic examination is presently performed each year. Women should be asked about interval bleeding or abnormal vaginal discharge.

Preconception Counseling and Prenatal Care

DES-exposed patients need counseling prior to their becoming pregnant. They need information on the risks of infertility and pregnancy complications, including premature labor and delivery, ectopic pregnancy, and miscarriage. Procedures that may be appropriate for DES-exposed women prior to and during pregnancy include a pelvic examination to check for cervical changes (e.g., collars, hoods, septae, and cockscombs) and an HSG. (Please refer to DES Resources for information on DES counseling.)

Exposure to DES in utero may impair a woman’s ability to give birth to a full term, live infant. Thus, prenatal care is particularly critical for women who were exposed to DES. All pregnancies of DES-exposed daughters should be considered high-risk pregnancies.

Ectopic pregnancies and spontaneous abortions occur more frequently in DES-exposed women than in non–DES-exposed women. As soon as a pregnancy is confirmed, ß-HCG titers should be obtained every 48 hours until an intrauterine pregnancy is certain. A vaginal ultrasound is also helpful to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Starting with the 12th week of pregnancy, regular inspection and palpation of the cervix allow the clinician to detect any changes of cervical effacement and dilation. The patient should undergo such an examination at least every 2 weeks. During the third trimester of pregnancy, patients should receive information regarding the signs and symptoms that may indicate the onset of pre-term labor. Patients at this stage of gestation should have weekly examinations.

Due to reports of DES-exposed women having worse reproductive outcomes than women with normal uterine anatomy, in the past the use of prophylactic cerclage has been advocated for all pregnant DES exposed women. The diagnosis of premature cervical dilation is relatively uncommon, even for the DES exposed woman. Kaufman and colleagues (2000) reported a similar pregnancy outcome in patients having cerclage compared to those individuals who did not undergo this procedure. Some clinicians limit the use of cerclage among DES-exposed women to those who meet the criteria for emergent or prophylactic cerclage placement, which are history compatible with incompetent cervix and sonogram demonstrating funneling or clinical evidence of extensive obstetric trauma to cervix.

Levine and Berkowitz (1993) studied the effectiveness of conservative management and limited cerclage use in DES exposed women with upper genital tract or cervical abnormalities as compared with DES-exposed women without associated changes. They also took into account intrapartum events to assess the relationship between gross structural abnormalities and specific labor complications. They found that the majority of pregnancy losses in DES exposed patients occurred in the first trimester. Cervical incompetence was an infrequent cause of pregnancy loss even in patients with gross structural abnormalities of the genital tract. When the patients were conservatively managed, there were good pregnancy outcomes, and the study suggests that prophylactic cerclage should not be a routine approach for DES-exposed women who become pregnant.

Researchers are currently examining the effects of DES exposure on the grandchildren of women prescribed DES while pregnant. Some animal studies have shown increased tumor rates in third-generation mice as they age. A small clinical study did not find evidence of structural reproductive abnormalities in 28 DES granddaughters (Kaufman et al, 2000). A larger survey is under way to determine if there are increased risks of reproductive problems and cancer. The findings of Klip and associates (2002), who studied the sons of a Dutch cohort of women who had been exposed to DES in utero, suggested that these sons may have an increased risk of hypospadias; however, further study is necessary.

There are several DES resources for clinicians and patients.

CDC's DES Update

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

4770 Buford Highway, NE Mailstop F-29

Atlanta, GA 30341-3724

Phone: (toll-free) 1-888-232-6789

E-mail: ncehinfo@cdc.gov

http://www.cdc.gov/des/

DES Action USA

610 16th Street, Suite 301

Oakland, CA 94612

Voice: (510) 465-4011

Fax: (510) 465-4815

E-mail: desaction@earthlink.net

A national consumer organization representing DES mothers, daughters, and sons. Dedicated to informing the public and health professionals about the effects of DES and what can be done about them, and to promoting DES research. Offers physician referrals, special publications, and a quarterly newsletter (DES Action Voice).

DES Cancer Network

514 10th Street, NW

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20004-1403

Voice: (800) DESNET-4, (202) 628-6330

Fax: (202) 628-6217

E-mail: desnetwrk@aol.com

Web site: www.descancer.org

A national network for DES-exposed women and men with a special focus on DES research advocacy, programs for DES-exposed people coping with cancer, and communication about DES issues. Offers information, peer support, medical referrals, and a newsletter (DES Issues).

DES Sons Network

DES Action/DES Sons Network

104 Sleepy Hollow Place

Cherry Hill, NJ 08003

Voice: (856) 795-1658

Fax: (856) 795-1658

E-mail: msfreilick@hotmail.com

A national network providing information and support for men exposed to DES before birth (DES Sons), and counseling for men with testicular cancer.

DES Third Generation Network

Box 21

Mahwah, NJ 07430

E-mail: des3gen@aol.com

An advocacy network designed to collect and share information about the health of children born to DES Daughters (women exposed to DES before birth [in the womb]) and DES Sons (men exposed to DES before birth [in the womb]).

National Cancer Institute

Cancer Information Service

M-F 9:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.

1-800-4-CANCER or 1-800-422-6237

cancer.gov

LiveHelp

A national service providing free, accurate, up-to-date information on cancer to patients and their families, to health professionals, and to the general public.

Registry for Research on Hormonal Transplacental Carcinogenesis

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

The University of Chicago

5841 South Maryland Avenue

Mail Code 2050

Chicago, IL 60637

Voice: (773) 702-6671

Fax: (773) 702-0840

An international research registry of cancer patients with clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA) of the vagina and/or cervix or other gynecologic cancer who may or may not have been exposed to DES or other synthetic hormones while in utero. A resource for clinicians and scientists, the Registry was established in 1971 to centralize data collection on CCA and enable us to learn more about the epidemiology and pathology of these tumors.

Nonsteroidal Estrogens

Benzestrol

Chlorotrianisene

Comestrol

Cyren A.

Cyren B.

Delvinal

DES

Desplex

Dibestil

Diestryl

Dienostrol

Dienoestrol

Diethylsteilbestrol dipalmitate

Diethylstilbestrol diphosphate

Diethylstilbestrol dipropionate

Diethylstilbenediol

Digestil

dinestrol

Domestrol

Estilben

Estrobene

Estrobene DP

Estrosyn

Fonatol

Gynben Gyneben

Hexestrol

Hexoestrol

Hi-Bestrol

Menocrin

Meprane

Mestilbol

Microest

Methallenestril

|

Mikarol

Mikarol Forti

Milestrol

Monomestrol

Neo-Oestranol I

Neo-Oestranol II

Nulabort

Oestrogenine

Oestromenin

Oestromon

Orestol

Pabestrol D

Palestrol

Restrol

Stil-Rol

Stilbal Stilbestrol

Stilbestronate

Stilbetin

Stilbinol

Stilboestroform

Silboestrol

Stilboestrol DP

Stilestrate

Stilpalmitate

Stilphostrol

Stilronate

Stilrone

Stils

Synestrin

Synestrol

Synthosestrin

Tace

Vallestril

Willestrol

|

Nonsteroidal Estrogen-Androgren Combination

Amperone

Di-Erone

Estan

Metystil

Teserene

Tylandril

Tylostereone

Nonesteroidal Estrogen-Progesterone Combination

Progravidium

Vaginal Cream Suppositories with Nonsteroidal Estrogens

AVC Cream with Dienestrol

Dienestrol Cream |

Source: National Cancer Institute. Exposure in utero to diethylstilbestrol and related synthetic hormones. JAMA 1976 Sept 6; 236 (10): 1107-1109.

Blair, P. B. (1981). Immunological consequences of early exposure of experimental rodents to diethylstilbestrol and steroid hormones. In R. A. Bern & A. L. Herbst (Eds.), Developmental effects of diethylstilbestrol (DES) in pregnancy (pp. 167–178). New York: Thieme-Stratton.

Cousins, L., et al. (1980). Reproductive outcome of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 56, 70–76.

Goldstein, D. P. (1978). Incompetent cervix in offspring exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 52(Suppl. 1), 73–75.

Hatch, E. E., et al. (1998). Cancer risk in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 630–634.

Hornsby, P. P., et al. (1994). Effects on the menstrual cycle of in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 170, 709–715.

Kaufman, R. H., et al. (2000). Pregnancy outcomes in diethylstilbestrol-exposed offspring: Continued follow-up. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 96, 483–489.

Klip, H., et al. (2002). Hypospadias in sons of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero: A cohort study. Lancet, 359, 1081–1082.

Levine, R. U., et al. (1993). Conservative management and pregnancy outcome in diethylstilbestrol exposed women with and without gross genital tract abnormalities. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 169, 1125–1129.

Ludmir, J., et al. (1987). Management of the diethylstilbestrol exposed patient: A prospective study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 157, 665–669.

Mangan, C. E., et al. (1982). Pregnancy outcome in 98 women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero, their mothers, and unexposed siblings. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 59, 315–319.

Menczer, J., et al. (1986). Primary infertility in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 93, 503–507.

Noller, K. L., et al. (1988). Increased occurrence of autoimmune disease among women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Fertility and Sterility, 49, 1080–1082.

Palmer, J. R., et al. (2001). Infertility among women exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154, 319–321.

Palmer, J. R., et al. (2002). Risk of breast cancer in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero: Preliminary results (United States). Cancer Causes and Control, 13, 753–758.

Rosenfeld, D. L., et al.(1980). Reproductive problems in the DES-exposed female. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 55, 453–456.

Schmidt, G., et al. (1980). Reproductive history of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Fertility and Sterility, 33, 21–24.

Senekjian, E. K., et al. (1988). Infertility among daughters either exposed or not exposed to diethylstilbestrol. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 158, 493–498.

Thorp, J. M., et al. (1990). Antepartum and intrapartum events in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 76, 828–832.

Back to Top |