|

Botanists are notorious for inventing all sorts of terms to explain different floral phenomena, but one of the most interesting is called "cauliflory." This term may be literally translated into "stem-flower." Under a strict definition it refers to flowers and inflorescences that develop directly from the trunks, limbs and main branches of woody plants.

|

Napoleona imperialis, a tree from tropical West Africa with large, showy blossoms that develop on the main trunk. It belongs to the Lecythidaceae, along with the canonball tree (Couroupita guianensis) shown later in this article. Some botanists have placed Napoleona in the Barringtoniaceae, and others believe it warrants its own family, the Napoloeonaceae.

|

In the vast majority of woody angiosperms, flowers open from buds that develop on new growth or young leafy stems. In some cauliflorous species, flowers are produced on young, leafy branches, as well as farther down on their main trunk and limbs. Some plants appear to be cauliflorous, including the bottlebrushes Callistemon and Melaleuca, because their seed capsules appear to grow out of the main stems and branches; however, they are not truly cauliflorous because their flowers develop at the tips of young stems. Although cauliflory is widespread in many different plant families throughout arid and temperate regions of the world, it is most prevalent in the tropical rain forest. In a distinct zone below the forest canopy, many cauliflorous trees and shrubs offer their "stem-flowers" to a wide variety of pollinators. Because there are so many different animal species that visit these flowers (including birds, bats, climbing mammals and insects), it is difficult to generalize about any particular animal group that specializes in cauliflory. One thing for sure, the accessibility of these flowers and seed-bearing fruits on the trunks and limbs of trees appears to be an important factor in why pollinators and frugivores (fruit-eaters) are attracted to them.

|

Brownea macrophylla, a tropical leguminous shrub with large, showy blossoms that develop on the main trunk and limbs. This photo was taken by Mr. Wolffia near Golfito, on the humid Pacific coast of southern Costa Rica.

|

A brief search of the botanical literature will reveal more than one hundred species of cauliflorous plants distributed in dozens of different plant families. Although the vegetable "cauliflower" (Brassica oleracea) has the same name, it is not a good example of cauliflory. Like its close cousin, "broccoli" (another variety of B. oleracea), it is essentially a dense cluster of unopened flower buds arising from a main flower stalk. Actually, cauliflower is derived from the Latin terms "caulis" (cabbage) and "floris" (flower), while broccoli is an Italian word taken from the Latin "brachium," meaning an arm or branch. In yet another variety of B. oleracea, called brussels sprouts, clusters of leafy buds resembling miniature cabbage heads are clustered along the main stem axis. Although one or more of these vitamin-rich, nutritious vegetables of the mustard family (Brassicaceae) should be included in a healthy diet, none of them are true examples of cauliflory.

|

Moreton bay chestnut (Castanospermun australe), an evergreen leguminous tree native to eastern Australia. The flowers are often produced in lateral racemes that arise from the main trunk. The fruits contain large, globose seeds that superficially resemble chestnuts.

|

With respect to the adaptive advantage of cauliflory, it is difficult to generalize because there are so many different pollinators that visit these flowers. According the famous plant evolutionist G. Ledyard Stebbins (Flowering Plants--Evolution Above The Species Level, 1974), the adaptive significance of cauliflory appears to be chiefly associated with cross pollination. Since the flowers of most species are not self-fertilized, they must be visited by animal vectors. It is well known that insect fauna of rain forests are distributed in horizontal layers at various heights above the ground. Many cauliflorous species have capitalized on an insect fauna that lives near the ground level. According to Stebbins, present-day cauliflorous species living in the rain forest understory may have descended from ancestors that lived in more open habitats. Larger cauliflorous blossoms are generally fairly sturdy and well-attached, and can withstand the probing of larger birds and mammals. Perhaps equally important are the large fruits which are readily accessible to frugivores that disperse the seeds of these plants. Animal visitors of cauliflorous species can be categorized into the following four general classes.

|

(1) Marsupial and placental mammals that climb on trunks and sturdy limbs to feed on the nectar and fruits.

(2) Perching birds that typically land on limbs to feed on the fruits.

(3) Pollinator and frugivore bats that cling to the trunk and limbs while feeding. This is especially true of bats that relish the cauliflorous fruit clusters on tropical figs (Ficus species). It is also true that "bat flowers" are often produced by non-cauliflorous species in which the blossoms appear on long, rope-like stalks that hang from the forest canopy. Good examples of this "hanging method" are the tropical lianas (Mucuna species) and the infamous sausage tree (Kigelia pinnata).

(4) Small, crawling and flying insects that frequently visit the flowers below the forest canopy.

|

Some of the most notorious examples of cauliflory include the calabash tree (Crescentia cujete, Bignoniaceae), papaya (Carica papaya, Caricaceae), tropical figs (Ficus auriculata and F. capensis, Moraceae), American redbud (Cercis occidentalis, Fabaceae) and the infamous chocolate tree (Theobroma cacao, Sterculiaceae). There are many other remarkable examples, including the brilliant red-flowered Brownea macrophylla (Fabaceae), the unusual cauliflorous bottlebrush Calothamnus validus (Myrtaceae), the striking red-flowered Woodfordia fruticosa (Lythraceae), and the yellow-flowered Halleria lucida (Scrophulariaceae). The latter plant belongs to the snap-dragon family, and produces typical snap-dragon or penstemon-like blossoms, except they grow out of the main limbs.

|

Halleria lucida, a striking cauliflorous shrub from tropical Africa. It belongs to the Snapdragon Family (Scrophulariaceae), along with foxgloves (Digitalis), penstemons (Penstemon), and snapdragons (Antirrhinum).

|

|

The North American redbud (Cercis canadensis) is a beautiful cauliflorous legume in the eastern United States. It is replaced in California, Arizona and Utah by the western redbud (C. occidentalis).

|

|

Davidson's plum (Davidsonia pruriens), a cauliflorous tree from rain forests of northeastern Australia. Since there is only one species (and one genus) in the Davidsoniaceae, this family is termed monotypic. [Some botanists place Davidsonia in the family Cunoniaceae.] Although very acid when ripe, the plum-like fruits are edible and make excellent jams and jellies.

|

If you stretch the definition of cauliflory to include flowers and fruits that develop on short lateral shoots arising from the main trunk and limbs, then trees such as the carob (Ceratonia siliqua) and Tupidanthus calyptratus could be included in this discussion. At the San Diego Zoo and Balboa Park in San Diego County there are several examples of cauliflory including the carob tree, tupidanthus and the bushy yate (Eucalyptus lehmannii, Myrtaceae), an interesting shrubby eucalyptus commonly used for windbreaks and screens. The tropical Asian Tupidanthus calyptratus produces umbel-like clusters of flowers and fruits on stalks that grow directly out of the main trunk and limbs. A member of the aralia family (Araliaceae), this striking, shade-loving understory shrub has large palmately compound leaves.

Carob Tree (Ceratonia siliqua)

The flowers and pods of the carob tree (Ceratonia siliqua) often arise directly from the limbs and branches of female trees. [This species is predominately dioecious, with separate male and female trees; however, trees with both male and female flowers also occur in carob populations.] The pods (mostly mesocarp or pulp) are ground to make carob flour which is used as a chocolate substitute in candy, ice cream, brownies and cookies. Locust bean gum, a thickening agent in ice creams and salad dressings, comes from the ground seeds of the carob tree. The name St. John's bread comes from the fact that carob trees were the "locust" on which John the Baptist fed. In ancient times, carob seeds were used as units of weight for small quantities of precious gemstones because they were extremely uniform is size. An average carob seed weighs about 3 1/3 grains, just over 200 milligrams. [Note: Some references give 4 grains for a carob seed.] The "carat," our present-day, international unit for the weight of diamonds, is derived from the name "carob," in reference to carob seeds. One carat is precisely 200 milligrams.

|

Seed pods of the carob tree (Ceratonia siliqua) often grow directly from the main branches of this Mediterranean tree.

|

|

Carob Tree

(Ceratonia siliqua)

A cauliflorous leguminous

tree native to the eastern

Mediterranean region.

|

|

Seeds of the carob tree (Ceratonia siliqua) were once used as a standard for weighing precious gemstones. An average carob seed weighs about 3 1/3 grains, just over 200 milligrams. [Note: Some references give 4 grains for a carob seed.] The brass weight in photo is exactly one gram (1000 milligrams), or about 5 carob seeds. The "carat" is our present-day, international unit for the weight of diamonds. Carat is derived from the word "carob," in reference to the carob seed. One carat is precisely 200 milligrams. The diamond in the engagement ring shown above is 1.09 carats or 218 milligrams. Karat spelled with a "k" refers to the fineness or purity of gold. One karat is 1/24 or 4.2 percent pure gold in an alloy. 16-karot gold is 16/24 or 66.7 percent pure gold, while 24-karat gold is 24/24 or 100 percent pure gold.

|

|

A Cauliflorous Tree

From Australia:

Bushy Yate

(Eucalyptus lehmannii) |

|

The buds and flowers of bushy yate (Eucalyptus lehmannii) grow out of the trunk and limbs. This fast-growing Australian tree makes a dense, leafy barrier or screen in southern California.

|

Cauliflory In Figs (Ficus)

One of the most interesting examples of cauliflory is Ficus pretoriae, an unusual African fig planted at San Diego Wild Animal Park. The globose, fleshy structures which most people call fruits are attached directly to the main trunk and limbs. These hollow structures (called syconia) are actually lined on the inside with minute unisexual male and female flowers. They are unique to the genus Ficus and the closely-related genus Dammaropsis (now referred to as Ficus dammaropsis), both members of the mulberry family (Moraceae). Like all the other 1000 species of figs, F. pretoriae is pollinated by a minute symbiotic agaonid wasp that is unique to this African fig. Although the symbiotic wasps of several other cultivated figs have been introduced into southern California, I have never seen the pollinator for F. pretoriae in our state. Another marvelous cauliflorous fig (F. auriculata) grows in San Diego County at Quail Botanic Garden and inside the Botanical Building near the Museum of Art in Balboa Park.

|

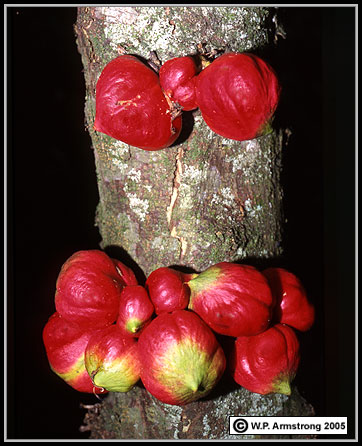

Ficus pretoriae, an interesting African fig with cauliflorous syconia (hollow structures lined on the inside with minute unisexual flowers). In true cauliflory fashion, the flower-bearing syconia arise from the main trunk and limbs.

|

|

Appearing like clusters of mushrooms, the flower-bearing syconia of Roxburgh Fig (Ficus auriculata) develop on the main trunk and near the ground.

|

A remarkable tree native to the Guanacaste Province of Costa Rica is known locally as "palanco" (Sapranthus palanga). It produces large, purple flowers and large, thick-walled fruits directly from its main trunk. Like several other members of the annona family (Annonaceae), including soursop (Annona muricata), cherimoya (A. cherimola), sugar apple (A. squamosa) and custard apple (A. reticulata), the large-seeded fruits attract a variety of animals. Unlike most other cauliflorous species, the blossoms of palanco are pollinated by carrion beetles and flies because they have a strong odor resembling a rotting carcass.

The Cacao Or Chocolate Tree

Several well-known cauliflorous species are the source of delicious and economically important products. The chocolate or cacao tree (Theobroma cacao) is believed to have originated in the Amazon Basin on the eastern equatorial slopes of the Andes. It is a small, shade-loving understory tree of wet tropical lowland forests. Many Indian tribes believed the plant came from the gods, hence the generic name Theobroma, meaning "food of the gods." In fact, it was so revered by native people that the seeds were used as currency by Aztecs and Mayas. In true cauliflory fashion, the curious blossoms grow directly out of the main trunk and branches. According to Daniel Janzen (Costa Rican Natural History, 1883), the flowers are believed to be pollinated by small ceratopogonid midges, although other small moths and beetles may be involved. The large, oblong fruits contain five rows of large seeds which are roasted and processed into cocoa. The seeds are dispersed by small mammals and monkeys as they break through the pod wall and eat the sugary pulp, leaving the seeds behind. Humans are very fond of the powdered seeds, especially when they are blended with milk and sugar to make highly caloric, heavenly-flavored confections, desserts and drinks. The seeds also contain the alkaloid theobromine, a caffeine relative with many reputed attributes, from a mild stimulant to a pleasant aphrodisiac. The latter quality may have evolved into the tradition of giving a box of these tasty morsels to a special romantic friend.

|

Cacao (Theobroma cacao) is a well-known cauliflorous tree with flowers and fruits that develop on the main trunk and branches. The ground seeds are the source of chocolate.

|

|

The fruit of cacao (Theobroma cacao) attached to the main trunk of a small tree. The ground seeds are the source of chocolate.

|

The Papaya Tree

If you have visited a country south of the Tropic of Cancer, you have probably noticed cauliflorous papaya fruits attached to the main trunk of this unusual tropical tree. Papaya (Carica papaya) is a small, typically unbranched, fast-growing tree with large palmately-lobed leaves. Its precise point of origin has been debated by botanists for years, but it is thought to be native to southern Mexico and Central America. Although the fruits are attached to the main trunk, they originated from female flowers near the apex of the trunk--so this species is not truly cauliflorous; however, another species (C. cauliflora) does produce flowers on its main trunk and is indeed cauliflorous. In addition to their incredibly delicious flavor, the sweet fruits are also the source of the natural enzyme papain. This valuable proteolytic enzyme is used in meat tenderizers, chewing gum, cosmetics, and as an effective treatment for simple digestive ailments. Papain is also synthesized from a genetically-engineered gene.

|

Cauliflorous fruits of papaya (Carica papaya) hang in clusters from the trunk of this common pantropical tree.

|

The Cannonball Tree

There are other unusual cauliflorous trees that are much too tropical for the Mediterranean climate of southern California. The canonball tree (Couroupita guianensis), a member of the tropical family Lecythidaceae, is native to the Guianas in northeastern South America. The large, fragrant blossoms develop on woody stalks that push right out of the thick bark and have no connection with the foliage at the top of the tree. Spherical, cannonball-like fruits are up to 8 inches in diameter, and often remain attached to the tangled flower stalks.

|

The trunk of this cannonball tree (Couroupita guianensis) bears flowers and large, spherical fruits on tangled flower stalks.

|

Unknown Tree

|

This cauliflorous species may be Dysoxylum cauliflorum (Meliaceae)

|

The Jackfruit and Breadfruit Trees

The jackfruit tree (Artocarpus heterophyllus) bears massive fruits from the trunk and lower branches. Native to the Indo-Malaysian region, this tree is grown throughout the tropics for its pulpy, edible fruit. According to Charles Heiser (Seed To Civilization, 1973), the fruits may reach nearly three feet in length and weigh up to 75 pounds, thus making them perhaps the largest tree-bearing fruits on earth. Of course, the undisputed world's record for the largest fruit is a mammoth 1,061 pound pumpkin, a member of the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae). Jackfruit and its close relative, breadfruit (A. altilis), belong to the diverse mulberry family (Moraceae). Since individual jackfruits are composed of many ripened ovaries from many densely-packed female flowers, they are technically referred to as multiple fruits. The breadfruit is native to Polynesia where it is baked, boiled or fried as a starchy, potato-like vegetable and made into bread, pie and puddings. In 1789 Britain sent Captain Bligh on the H.M.S. Bounty to Tahiti to collect breadfruit cuttings for introduction into the New World colonies. Enchanted with the Tahitian way of life, the crew mutinied on the return voyage, putting Bligh off at sea in a small boat with 18 loyal followers. Bligh and his men survived a 3,618-nautical mile, 41-day trip to the East Indies. Undaunted, he returned to Tahiti on a second voyage and successfully introduced breadfruits into the West Indies in 1793.

|

The infamous breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) introduced from Polynesia into the West Indies by Captain Bligh himself.

|

The Calabash Tree

Any discussion of cauliflory would be incomplete without mentioning the remarkable calabash tree. There are two species that grow wild in Mexico, Central and South America, Crescentia alata and C. cujete. Crescentia alata is often placed in the genus Parmentiera and is listed as P. alata. Crescentia cujete is easy to identify because it has simple leaves and its gourd-like fruits are much larger (up to ten inches in diameter). Both species belong to the bignonia family (Bignoniaceae), along with Catalpa and Jacaranda, and their flowers develop from buds that literally grow out of the main trunk and limbs. Like many other large-flowered cauliflorous species, calabash trees are commonly pollinated by small bats of the genera Glossophaga and Artibeus. According to Daniel Janzen (1983), the pollen is in the dorsal (upper) side of the flower and is placed on the head and shoulders of the bat. After pollination the spectacular calabash fruits begin to develop along the trunk and limbs. A crop of 100 or more of these large, green, gourd-like spheres may adorn the tree for up to seven months, before turning yellow-green and eventually falling to the ground. On the lovely Caribbean island of Dominica, Carib Indians carve elaborate designs into the woody gourds during this "softer" green stage. Because the gourds are so large and hard-shelled, no native New Word herbivores can crack them open, and the rotting gourds litter the ground beneath old calabash trees. It is well documented that horses can break open the hard shell with their mouth and eat the sweet pulpy mass inside, dispersing the seeds in their dung. In Africa, large woody pods of other species are quickly devoured by large herbivores. According to D.H. Janzen and P.S. Martin (Science Vol. 215, 1982), large grazing mammals, including extinct pleistocene elephants called gomphotheres, may have once eaten the huge gourds and dispersed the seeds in lowland forests.

|