| Big Dig |

Susan Moir

University of Massachusetts Lowell

The most expensive

highway construction project in the world, the Central Artery/Tunnel (CA/T)

in Boston, Massachusetts, is scheduled for completion in 2005. Known as

the Big Dig, the project includes a new tunnel under the harbor connecting

Logan airport and interstate I-90, the Mass. Turnpike. The first section

of the tunnel, finished in 1995, is named for Boston baseball hero Ted

Williams.

Researchers from the Construction Occupational Health Program at the University

of Massachusetts Lowell have been conducting occupational health studies

on the Big Dig since 1992 under a mandate to improve health conditions

for workers in the regional construction industry. The research is part

of a nationwide consortium headed by CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training,

the research, development, and training arm of the Building and Construction

Trades Department, AFL-CIO, and funded by the National Institute for Occupational

Safety and Health, part of the CDC.

Full-time staff researchers and student research assistants have spent

countless hours on site observing, interacting with workers and dozens

of contractors, and seeking ways to reduce musculoskeletal injuries and

exposures to silica. The seven miles of tunnel that make up the project

are constructed mainly of concrete. Concrete is mostly made of sand and

sand is silica. Drilling, chipping, cutting, or otherwise abrading concrete

produces dust containing airborne crystalline silica. When inhaled, this

can cause silicosis, a deadly lung disease. While the dangers of silica

have been known since ancient times, the COHP's research has shown that

workers doing concrete construction are exposed to a much higher level

of silica than was known in the past. To prevent silica exposure and future

cases of silicosis, contractors need to plan ahead and provide proper

protection to workers.

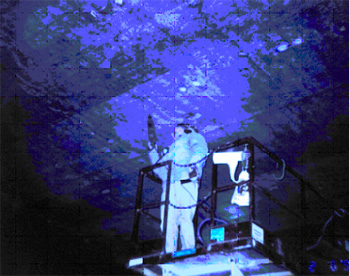

We first learned of this problem while watching the construction of the

Ted Williams Tunnel. We found workers on a scissor lift drilling approximately

17,000 holes in the concrete roof of the tunnel. We were told that hangers

would be epoxied into the holes to support the suspended ceiling ventilation

system. The workers doing the drilling were exposed to a mix of hazards

including silica dust and potential shoulder, neck, and back injuries

from using a heavy tool to drill overhead for hours at a time. It was

a very high hazard job.

We also noticed that the workers had added their own accessories, or "Bright

Ideas,"1 to make the job less hazardous. They had gone

to the hardware store and bought a household fan that they duct-taped

to the railing of the scissor lift to blow away the concrete dust that

was, as we now know, almost pure silica. They had also fashioned a pole

to hold up the drill and protect their shoulders and backs from injury.

We were told that this type of support is sometimes called a "soldier

pole" or an "inverse drill press."

This tunnel consisted of 13 pre-fabricated tube tunnel sections. Each

section had been lined with concrete before being sunk and connected on

the harbor floor. We asked why the holes had to be drilled after the concrete

liner had been constructed and why the holes were not designed into the

lining in the earlier formwork stage. Typical answers were that it had

to be done this way and that no one had really thought about the problem

in the design phase. Engineers on site told us that they had not been

able to plan for the holes because they did not know where they would

be needed until they began installation of the ceiling ventilation system.

We watched this job for more than two years and saw how hazardous and

difficult it was. We published a chapter in a book about the hazards involved.2

While we continued to raise questions about the hazards of the ceiling

ventilation system design, it took about three years to get a meeting

with the engineers who made the decisions about the designs.

At the meeting, the engineers said that we were not the only ones who

had raised questions about the design and that future designs had been

changed for reasons of health and safety, cost, and constructibility [ease

of construction]. As is often the case, the difficult and dangerous design

had also been very expensive. The new design eliminated the problem of

drilling holes for hangers by imbedding the supports for the ceiling ventilation

system in the tunnel roof during the concrete formwork stage of construction.

The first tunnel using the revised ceiling ventilation design, the I-90

Fort Point Channel tunnel, has been completed. According to Charlie Rountree,

safety and health manager for CA/T Managing Consultant Bechtel/Parsons

Brinckerhoff, the Ted Williams Tunnel ceiling ventilation system cost

about $55/sq. ft. The redesigned ceiling ventilation system cost about

$22/sq. ft. for a savings of approximately $33/sq. ft. in total installed

cost. Two additional tunnels under construction are expected to result

in similar savings.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to count the savings from injuries that

did not happen. However, as Rountree said, "We should always consider

safety and health, constructibility, and cost, in that order." There

is no doubt that redesigning the tunnel ceiling ventilation system prevented

some workers from getting career-altering musculoskeletal injuries and

life-threatening silicosis.

1 The COHP has published a series of "Bright Ideas," construction workers'

health and safety innovations on the job. They can be viewed on our website

at www.uml.edu/Dept/WE/COHP.

2 Brian Buchholz and Victor Paquet, Reducing ergonomic hazards during

highway construction: A case study of a tunnel ceiling panel assembly

operation. In: V. Rice, ed., Ergonomics in Clinical Practice, Butterworth-Heinemann,

Newton, Mass., 1998.

Worker drills overhead one of 17,000 holes in tunnel roof for hangers for suspended ceiling. The household fan added to blow way silica dust is taped to the corner of the lift.

Workers install

suspended ceiling in tunnel.

![]() This

document appears in the eLCOSH website with the permission of the author

and/or copyright holder and may not be reproduced without their consent.

eLCOSH is an information clearinghouse. eLCOSH and its sponsors are not

responsible for the accuracy of information provided on this web site,

nor for its use or misuse.

This

document appears in the eLCOSH website with the permission of the author

and/or copyright holder and may not be reproduced without their consent.

eLCOSH is an information clearinghouse. eLCOSH and its sponsors are not

responsible for the accuracy of information provided on this web site,

nor for its use or misuse.

Susan Moir,

MSc, is former director of the Construction Occupational Health Program

at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

![]() eLCOSH

| CDC | NIOSH

| Site Map | Search

| Links | Help

| Contact Us | Privacy Policy

eLCOSH

| CDC | NIOSH

| Site Map | Search

| Links | Help

| Contact Us | Privacy Policy