Pacific Bigeye Tuna (Thunnus obesus)

- Pacific bigeye tuna population levels are high.

- Pacific bigeye tuna is a highly migratory fish stock and requires cooperative international management to be sustainable. The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission are the regional fishery management organizations (RFMOs).

- In general, tuna is low in saturated fat and sodium and is a very good source of protein, thiamin, selenium, and vitamin B6. For more on nutrition, see Nutrition Facts. (USDA)

- Fisheries in the Pacific Ocean account for about half of the world’s harvest of bigeye tuna. However, the U.S. West Coast catch makes up less than 1% of the eastern Pacific Ocean catch of this species, and only about 5% of the harvest in the Western Pacific comes from Hawaii-based fisheries.

|

|

|

|

|

| Nutrition Facts |

| Servings 1 |

| Serving Weight

100g |

|

| Amount Per Serving |

|

| Calories N/A |

|

| Total Fat |

N/A |

|

| Total Saturated Fatty Acids |

N/A |

|

| Carbohydrate |

N/A |

| Sugars |

N/A |

| Total Dietary

Fiber |

N/A |

|

| Cholesterol |

N/A |

|

| Selenium |

N/A |

|

| Sodium |

N/A |

|

| Protein |

N/A |

|

|

|

A fishery observer measuring a bigeye tuna. Bigeye tuna of sashimi size and quality are the most valuable of the tropical tunas. A fishery observer measuring a bigeye tuna. Bigeye tuna of sashimi size and quality are the most valuable of the tropical tunas.

|

|

Did you know?

The largest recreationally caught bigeye tuna in the Pacific is a 435 pound fish caught off Cabo Blanco, Peru in 1957.

Tropical tuna (like bigeye) caught in the U.S. purse seine fishery are canned as light meat tuna.

In the Hawaii longline fishery, 12 to 25 hooks are deployed between floats with lots of sag to reach as deep as 1,300 feet to target deep-swimming bigeye tuna. Luminescent light sticks are used at night to attract bigeye tuna or their prey, and longlines are baited with large imported squid.

|

|

| |

|

|

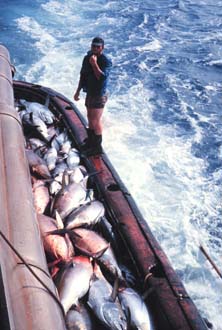

Bigeye tuna caught with three-pole one-line rig. Adult bigeye tuna are caught mainly by longlines, but substantial numbers of juveniles are taken by purse seines.

|

|

|

Bigeye tuna are believed to have recently evolved from a common parent stock of yellowfin tuna.

|

|

Sustainability Status

Biomass: Bigeye tuna biomass is above the biomass needed to support maximum sustainable yield (BMSY) in both the western and eastern Pacific Oceans, at 25% and 15% above BMSY, respectively. However, IATTC recently concluded that the eastern Pacific stock is probably overexploited because the stock size is smaller than that needed to support MSY (SMSY) and overfishing is occurring. Little progress has been made to reduce fishing effort internationally. The U.S. is working with RFMOs to create a resolution that will decrease fishing effort internationally.

Overfishing: Yes

Overfished: No

Fishing and habitat: On the U.S. West Coast, bigeye tuna are commercially caught in the coastal purse seine fishery. Bigeye is also taken incidentally in the drift net fishery for swordfish and shark and in the surface fishery for albacore. In the Western Pacific, bigeye is primarily harvested by pelagic longline, pole and line, and purse seine gears. Purse seining and pole and line target fish near the surface and longlines fish as deep as several hundred meters, but none of these methods interact with the seafloor or benthic habitats.

Bycatch: There is little or no bycatch in the small pole and line fishery for bigeye tuna. Bycatch in both the purse seine and longline fisheries is monitored through logbook and vessel observer programs. The primary bycatch in the purse seine fishery is other tuna species. There are also some interactions with sea turtles but mortality is estimated to be low. The largest component of bycatch in the longline fishery is sharks, particularly blue shark. Area closures and gear restrictions have been very successful in minimizing the bycatch of sharks, marlins, and protected species. The longline fishery also had significant interaction with sea turtles and several species of seabirds, but subsequent regulations have substantially lowered interaction rates. Longline vessels are required to use specific mitigation measures to avoid catching sea turtles and seabirds and increase the likelihood of their survival after being released.

Aquaculture: There is currently no commercial aquaculture of bigeye tuna in the United States.

|

Science and Management

Off the U.S. West Coast, bigeye tuna is managed by the Pacific Fishery Management Council through the Highly Migratory Species (HMS) Fishery Management Plan. There are currently no quotas for HMS species but there are harvest guidelines (general objectives for harvest rather than a specific amount which, when reached, triggers the closure of a fishery). New monitoring requirements were implemented for the West Coast fishery in 2005. Commercial fishers must obtain a permit from NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to fish for HMS and maintain logbooks documenting their catch. Recreational charter vessels must also keep logbooks. If requested by NMFS, a vessel must carry a fishery observer. These measures are intended to improve data collection about HMS catches.

Hawaii's bigeye tuna fisheries are managed through the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council's Pelagics Fishery Management Plan. There is a limited entry system in place for the Hawaii longline fishery. Longline exclusion zones have been established around the main Hawaiian islands and northwestern Hawaiian islands and are enforced through NMFS mandatory Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) policy, where local longline boats must be equipped with a satellite transponder that provides real-time position updates and track vessel movements. Hawaii-based longline vessels must also carry onboard observers when requested by NMFS, in part, to record interactions with sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Since bigeye tuna moves throughout large areas of the Pacific and is fished by many nations and gear types, management by the United States alone is not enough to ensure that harvests are sustainable in the long term. The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) is an international commission with U.S. membership that provides the framework for conservation and management of tuna resources in the eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO). In the EPO, the IATTC has implemented management measures for purse seine and longline fisheries in response to concerns about the condition of eastern Pacific bigeye tuna. Purse seiners also operate under the Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program, a multilateral agreement aimed at reducing and minimizing bycatch of dolphins and undersize tuna (Dolphin Safe tuna).

U.S. purse seine vessels operate throughout the central and western Pacific under conditions of the South Pacific Tuna Treaty (SPTT). Vessels are monitored through logbooks, cannery landing receipts, national surveillance activities, observers, and port sampling. They must also be entered into the Forum Fisheries Agency Regional Register of Foreign Fishing Vessels and Vessel Monitoring System Register.

The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), an intergovernmental organization with authority to manage HMS in the western and central Pacific Ocean, was established in 2004. Congress recently ratified U.S. membership on the Commission. Management measures include bigeye longline catch limits, purse seine effort limits, and fishery capacity limits in other fisheries that take bigeye tuna. Some of the latter two measures are implemented in the U.S. The U.S. also has responsibilities under the United Nations Agreement on the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and High Migratory Fish Stocks (known as the UNIA). The U.S. is also a member of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), which has implications for HMS management. In 1995 the FAO's Committee on Fisheries developed a Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, which more than 170 member countries, including the U.S., have adopted.

|

Life History and Habitat

Life history, including information on the habitat, growth, feeding, and reproduction of a species, is important because it affects how a fishery is managed.

- Geographic range: Bigeye tuna are found across the Pacific Ocean between northern Japan and the north island of New Zealand in the western Pacific and from 40°N to 30°S in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Bigeye are also found in the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

- Habitat: Bigeye tuna are most common in warm surface waters between 30°N and 20°S in the Pacific. They are relatively more abundant in the western and eastern Pacific compared to the central Pacific. They favor clean, clear oceanic waters between 55°F and 84°F.

- Life span: Bigeye tuna can live up to more than 10 years. They are long-lived in comparison to yellowfin tuna but not as long-lived as bluefin tuna.

- Food: Bigeye tuna are opportunistic feeders, preying primarily on crustaceans, cephalopods, and fishes.

- Growth rate: Rapid during their first few years, then slower thereafter.

- Maximum size: Up to 6.5 feet.

- Reaches reproductive maturity: Bigeye tuna mature around age 3 at about 3 to 3.3 feet in length.

- Reproduction: Bigeye are serial spawners, capable of spawning almost daily with millions of eggs per spawning event. Eggs are epipelagic (found in the top layer of the ocean). They are buoyed at the surface by a single oil droplet until they hatch.

- Spawning season: Throughout the year in tropical waters and seasonally at higher latitudes at water temperatures above 73° F.

- Spawning grounds: Mainly in tropical waters at or near the surface.

- Migrations: Bigeye tuna are capable of large-scale movements which have been documented by tag and recapture programs. They move freely within broad regions of favorable water temperature and dissolved oxygen levels. Juveniles and small adults of bigeye tuna school at the surface, sometimes with yellowfin tuna and/or skipjack. Schools may be associated with floating objects.

- Predators: The main predators of bigeye are large billfish and toothed whales.

- Commercial or recreational interest: Both

- Distinguishing characteristics: Bigeye tuna are dark metallic blue on the back and upper sides and white on the lower sides and belly. Their first dorsal fin is deep yellow, the second dorsal and anal fins are pale yellow, and the finlets are bright yellow with black edges.

|

Role in the Ecosystem

During spawning, bigeye tunas’ buoyant eggs are released and float at the surface where they become part of the zooplankton and food for the many organisms and small fish feeding in the equatorial surface waters. Larval bigeye tuna begin feeding on the same zooplankton that they are a part of. Fully formed juveniles begin eating small fish, crustaceans, and squid. These juveniles also begin to move north and south of equatorial waters and are often preyed upon by larger tunas and billfish. Larval and juvenile bigeye are also eaten by other fish, seabirds, porpoises, and other animals. After about one year, the adult bigeye is an opportunistic predator with a highly varied diet of fish, crustaceans and squid. It is also now prey to larger tunas and billfish. Larger juveniles (above 14 inches) and adults are sought after in recreational and commercial fisheries for human consumption.

|

Additional Information

Market name: Tuna

Vernacular names: Big Eye, Ahi-b

|

Biomass

Biomass refers to the amount of Pacific bigeye tuna in the ocean. Scientists cannot collect and weigh every single fish to determine biomass, so they use mathematical models to estimate it instead. These biomass estimates can help determine if a stock is being fished too heavily or if it may be able to tolerate more fishing pressure. Managers can then make appropriate changes in the regulations of the fishery.

Biomass refers to the amount of Pacific bigeye tuna in the ocean. Scientists cannot collect and weigh every single fish to determine biomass, so they use mathematical models to estimate it instead. These biomass estimates can help determine if a stock is being fished too heavily or if it may be able to tolerate more fishing pressure. Managers can then make appropriate changes in the regulations of the fishery.

In the Eastern Pacific Ocean, bigeye biomass increased in the early 1980s and peaked in 1986 at about 626,000 metric tons. Biomass has been declining since 1987, initially because of the impact of longline fishing and, since 1993, purse seining (with fish aggregating devices). The decline was interrupted by strong recruitment from 1995 to 1998, which produced a peak biomass in 2000, after which it decreased to an historic low of about 270,000 tons at the beginning of 2007. Spawning biomass has followed a similar trend. Both biomasses are estimated to have increased slightly recently. While biomass estimates are somewhat uncertain, it is apparent that fishing has reduced the total biomass of bigeye in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

In the Western and Central Pacific, biomass is estimated to have declined during the 1950s and 1960s then was relatively stable through the 1970s and 1980s. From 1990 onwards, biomass has declined steadily.

Note: The Western and Central Pacific biomass estimates shown in the graph are the first quarter estimates from the base case. However, there are estimates of biomass from four other models that scientists and managers consider when making management decisions.

Landings

Landings refer to the amount of catch that is brought to land. The only significant U.S. longline fishery targeting Pacific bigeye tuna at this time is based in Hawaii. Approximately 95% of Hawaii-based longline landings are from the Western Pacific, and the largest component of Hawaii’s pelagic catch is bigeye tuna. Catch of bigeye tuna by U.S. West Coast fisheries constitutes less than one percent of the Eastern Pacific-wide catch.

Landings refer to the amount of catch that is brought to land. The only significant U.S. longline fishery targeting Pacific bigeye tuna at this time is based in Hawaii. Approximately 95% of Hawaii-based longline landings are from the Western Pacific, and the largest component of Hawaii’s pelagic catch is bigeye tuna. Catch of bigeye tuna by U.S. West Coast fisheries constitutes less than one percent of the Eastern Pacific-wide catch.

Note: U.S. commercial landings are shown in the graph.

Biomass and Landings

Are landings and biomass related? Landings are dependent on biomass, management measures in the fishery, and fishing effort.

Are landings and biomass related? Landings are dependent on biomass, management measures in the fishery, and fishing effort.

Data sources:

Biomass from 2008 Stock Assessment of Bigeye Tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, IATTC 2008 Status of Bigeye Tuna in the Eastern Pacific Ocean

Landings from NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service Annual Commercial Landings Statistics using "TUNA, BIGEYE" as Species and "PACIFIC" as State

|

Important Dates

1917 – Hawaii-based longline fishery begins

Early 1980s – Less than 15 longline vessels are active in Hawaii

1980s – Tuna longline effort expands to supply developing domestic and export markets for high quality fresh and sashimi grade tuna

1987 – Western Pacific Pelagics Fishery Management Plan (FMP) is implemented

Late 1980s-early 1990s – Swordfish and tuna targeting fishermen from longline fisheries of the Atlantic and Gulf states arrive in Hawaii (longline effort increases rapidly from 37 vessels in 1987 to 138 vessels in 1990)

Early 1990s – Hawaii longline fishery expands to about 150 vessels

1991 – Entry into Hawaii longline fishery halted by moratorium under Amendment 3 to the Pelagics FMP

1991 – Longline fishing is prohibited within 50 nautical miles of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to prevent interactions with endangered Hawaiian monk seals. Additional longline exclusion zones are established in mid-1991 through Amendment 5 to the Pelagics FMP (50-75 nautical miles around the main Hawaiian Islands and within 50 nautical miles of Guam) to prevent gear conflicts between longliners and smaller fishing boats targeting pelagic stocks.

1994 – Amendment 7 to the Pelagics FMP institutes a limited entry program for the Hawaii-based longline fishery to restrict effort

1994 – Mandatory Vessel Monitoring System policy is implemented for the Hawaii longline fishery through cooperation among NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the U.S. Coast Guard, and industry

2002 – Framework measure 2 (Pelagics FMP) requires measures to protect seabirds from longlines; Regulatory Amendment 1 implements measures to protect sea turtles from pelagic longlines

2004 – West Coast HMS FMP implemented

2005 – New monitoring requirements are implemented for West Coast fishery to improve data about HMS catches; commercial fishers must obtain a permit from NMFS to fish for HMS and maintain logbooks documenting their catch, recreational charter vessels must also keep logbooks, and if requested by NMFS, a vessel must carry a fishery observer

2005 – Amendment 11 to the Pelagics FMP is approved to implement a limited entry program for the American Samoa-based domestic longline fishery, which would constrain potential expansion of the fishery which has the largest domestic catches of Pacific bigeye tuna in the U.S. EEZ around American Samoa

2007 – Amendment 14 to the Pelagics FMP is approved to address ending overfishing of bigeye tuna in the Pacific

|

Notes and Links

General Information:

NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Southwest Fisheries Science Center - Pacific Ocean Tropical Tuna Research

NMFS Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC) Cruise Report - Bioacoustics survey to learn about the distribution and abundance of bigeye tuna and its prey at Cross Seamount

NMFS PIFSC Cruise Report - Scientists are studying the physiology of pelagic fishes and ways to reduce impacts of longline fishery bycatch

Pacific Fishery Management Council Backgrounder on Highly Migratory Species

Managing Marine Fisheries of Hawaii & the U.S. Pacific Islands - Past, Present & Future - Pelagic Fisheries

Fishery Management:

Pelagics Fishery Management Plan

Highly Migratory Species Fishery Management Plan

Stock Assessments:

Status of the U.S. West Coast Fisheries for HMS through 2007

2008 Stock Assessment of Bigeye Tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

Status of Bigeye Tuna in the Eastern Pacific Ocean in 2007

2007 Annual Report to the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

|

| |

|