The Inauguration

January 15, 2009

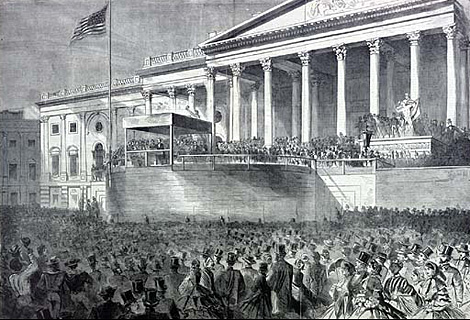

The Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as President, from Harper's Weekly, March 4, 1861, attributed to Winslow Homer

Greetings from D.C. where change comes every four—or sometimes eight—years. It's an interesting time to be in the nation's capital. On January 20th, our newest president will be sworn in; his election was a momentous achievement in so many ways. The same can be said for Abraham Lincoln who was sworn in as the nation's sixteenth president on March 4, 1861. Famed American artist Winslow Homer was in attendance and created this wood engraving on paper for Harper's magazine. It shows Lincoln delivering his remarks on the steps of the U.S. Capitol, under a specially designed canopy. Dignitaries fill the area behind him, while the well-dressed throngs below share Homer's perspective. The men wear hats, the women bonnets, while one woman in the foreground carries an parasol, presumably to shade herself from the glare of the sun.

Painter and graphic artist Winslow Homer, whose work is well represented at American Art, was known for his illustrations of the Civil War, also published by Harper's, and his luminous seascape paintings.

While you're at American Art, check out the exhibition, The Honor of Your Company is Requested: President Lincoln's Inaugural Ball. It gives an inside, behind-the-scenes look into American history and pageantry in the same building where Lincoln's second inaugural ball was held.

Since we're starting off a new year, I'm going to end this post with Lincoln's famous words from his second inaugural speech in 1865 as a new year's wish for 2009: "With malice toward none; with charity for all . . . ."

Related Info: Museum Special Programs and Temporary Closures during the Inaugural Weekend

Posted by Howard on January 15, 2009 in American Art Everywhere, American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (1)

Seeing Things (3): Seeing in the Dark

January 13, 2009

This is the third in a series of personal observations about how people experience and explore museums.

Bopping at Birdland (Stomp Time), from the Jazz Series by Romare Bearden

I think museums come to life at night. As the day draws to a close and evening begins to come on, I feel a sense of containment, as if the outside world is a kind of frame around my museum experience. What’s better than an evening at a museum while the world around you is settling down for the night: it’s magic. The day has so many expectations and obligations to it, but the night gives us a different sense of ourselves as well as of the city we live in. Maybe we’re a little freer at night, a bit more open to possibilities.

American Art is open till 7:00 p.m., which means you can visit after work, walk through the galleries, and end up in the Kogod Courtyard and watch the sky turn from light to darkness. Check out the online calendar for talks, lectures, and performances, such as Take Five! jazz concerts that add another dimension to the evening. On January 15 from 5 to 8 p.m., Eric Byrd leads the eight-piece Brother Ray Band, performing the music of Ray Charles. And while you're marking your calendar, add February 19 (same hours) to hear the Night and Day Quintet, featuring vocalist Renée Tannenbaum and pianist Michael Suser.

Related Posts: Seeing Things (1) and Seeing Things (2): Art and Love

Posted by Howard on January 13, 2009 in American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (1)

In This Case: Los Reyes Magos

January 6, 2009

Many people mistake days mentioned in the song "The Twelve Days of Christmas" for the days preceding December 25. In actuality, however, the song refers to the twelve days after Christmas. In the United States, our traditions tend to focus on family gatherings, large meals, Christmas trees, Santa Claus, and reindeer. In places across the world, particularly in Spanish speaking countries, January 6 is the main gift-giving holiday. The Day of the Kings, known as the Epiphany in the United States, shares many elements of the Christmas traditions. Children put out treats for the camels, often grass, along with some type of libation for Melchior, Gaspar, and Balthazar on the night of January 5. The kings bring presents only to good boys and girls. Apart from this, each country that celebrates the Day of the Kings has its own unique traditions, like parades, family gatherings or my favorite, eating rosca de reyes (king cake) with figurines hidden inside.

You might be asking yourself what this has to do with the Luce Foundation Center for American Art! On the third-floor mezzanine, in a dimly lit case (due to the material and fragility of the pieces, not because we don’t want you to see them), you will find this wooden sculpture that embodies the Puerto Rican tradition of the Day of the Kings. Los Reyes Magos (The Magi) was created in the late 1800s by Puerto Rico’s most notable family of santeros (carvers of wooden saints), the Caban Group. The three kings were revered as unofficial saints in Puerto Rico, which is most likely why the Caban Group depicted them. This piece breaks from the traditional iconography for the three kings found in western art. Instead of riding camels, the three men are on horseback. Similarly, Melchior, rather than Balthazar, is depicted as the black king, because according to local tradition, the rays of a star burned him.

You can find numerous examples of Latino art, including several depictions of the three kings, in the Luce Foundation Center. Case 21b, which houses Los Reyes Magos, showcases pieces from the collection of Puerto Rican historian and art collector Teodoro Vidal. You can also read more about Latino art in the American Art Museum’s collection in our online exhibit.

Mucha gente cree que la canción “Los 12 días de Navidad” se refiere a los doce días antes de la Navidad. En realidad, la canción se refiere a los 12 días después de Navidad. En los Estados Unidos, nuestras tradiciones navideñas tienen que ver con reuniones de la familia, grandes comidas, árboles de navidad, renos y Papá Noel. En muchos países del mundo, especialmente en los países hispanohablantes, el 6 de enero es el principal día festivo para dar y recibir regalos. Conocido como la Epifanía en los EEUU, el día de los Reyes Magos tiene mucho en común con nuestras tradiciones navideñas. En vísperas del día de los Reyes Magos, los niños dejan comida para los camellos y algo de beber para Melchor, Gaspar y Baltasar. Los Reyes solo traen regalos para los niños que se han portado bien durante todo el año. Además de eso, cada país tiene sus propias tradiciones, como desfiles, reuniones con la familia o mi favorita, la rosca de reyes con muñequitos escondidos adentro.

¿Qué tiene que ver el día de los Reyes Magos con el Luce Foundation Center? Por el tercer entrepiso, en una muestra poco iluminada (debido al material y la fragilidad de los objetos y no porque queramos que no se vea), se puede encontrar una escultura de madera que muestra unas de las tradiciones puertorriqueñas. Los Reyes Magos fue creado a finales del siglo diecinueve por el grupo Caban, una de las familias de santeros más conocidas de la isla. Es probable que el grupo Caban hiciera la escultura porque veneraban a los Reyes como si fueran santos en Puerto Rico. Esta escultura rompe con la iconografía tradicional de los Reyes Magos. En vez de estar en camellos, los reyes están en caballos. Asimismo, Melchor es el rey negro, en vez de Baltasar, debido a una leyenda puertorriqueña que dice que los rayos de una estrella quemaban a Melchor.

Se puede encontrar muchos ejemplos de arte latino, incluyendo algunas representaciones de los Reyes Magos, en el Luce Foundation Center. Además de Los Reyes Magos, la muestra 21b tiene algunos objetos de la colección del historiador y coleccionista puertorriqueño Teodoro Vidal. Se puede leer más sobre la colección de arte latino en una exposición en la red del American Art Museum.

- Day of the Kings, Los Reyes Magos, Caban Group, Puerto Rico, Luce Foundation Center for American Art, American Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Posted by Tierney on January 6, 2009 in American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (0)

It Takes a Pueblo: Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams

December 30, 2008

Left: Georgia O'Keeffe, Ranchos Church No.1, 1929, Oil on canvas, 18 3/4 x 24 inches, CR 664, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida, © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Right: Ansel Adams, Saint Francis Church Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico, c. 1929, Gelatin silver print, 13 5/16 x 17 9/16 inches, Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, ©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

I think of Ansel Adams as the Walt Whitman of American photography, creating "silent songs" about monumental landscapes. Georgia O'Keeffe, on the other hand, reminds me of Emily Dickinson. Of course, Dickinson hardly ever left the perimeter of Amherst, but it's not a geographic similarity they share, it's more a sensibility that goes beyond their solitary work. A Dickinson poem, or an O'Keeffe painting often presents the greatest reward to those who can see the deepest.

Natural Affinities, the exhibition of O'Keeffe and Adams' work currently up at American Art (thru January 4, 2009) is an ecstatic look at the work and lives two of the masters of the twentieth century. Adams captured the landscape in luminous black and white, yet in a voice that soars. O'Keeffe painted the world around her—sky, flower, skull—with an earthy palette that draws the viewer in. When both artists visions' overlapped, say in their take on the Saint Francis Church at Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico, the result is staggering.

Both artists created these works in 1929, around the time of their first meeting. Theirs would be a lifelong friendship, with some breaks, and each would be propelled into greatness by Alfred Stieglitz, artistic visionary and O'Keeffe's husband. Taking a look at the Ranchos church, O'Keeffe's is solid, yet it floats: at times it even aspires to flesh. In Adams' view, the church becomes a monolith, solid and earth-bound. Looking at one and then the other creates a dialogue, about painting, photography, and the very nature of seeing things.

The exhibition is filled with such wonders, but it's closing January 4. Take a look and let me know what you see. And as an added feature download our audio companion to the exhibition from our American Art podcast series on iTunes.

Posted by Howard on December 30, 2008 in American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (1)

States of Grace: Remembering Grace Hartigan (1922–2008)

December 23, 2008

Frank O'Hara by Grace Hartigan

"I didn't choose painting," Grace Hartigan once told an interviewer, "It chose me. I didn't have any talent. I just had genius."

I came to Grace Hartigan through her association with the poet Frank O'Hara. As a grad student in creative writing living in New York I became interested in O'Hara and his work. I learned about his deep friendship with the abstract expressionist painter Grace Hartigan, who died a few weeks ago in Maryland. Both synthesized high art and popular culture in their works and both could find inspiration in the everyday. Both Hartigan and O'Hara were integral to New York's vivid art scene that flourished (mostly) downtown following World War II.

In fact, the words on O'Hara's gravestone pay homage to his great friend; "Grace/to be born and live as variously as possible." In those two lines O'Hara intertwined his own self and that of Hartigan. To live variously would be to experience as widely as possible what wells up in existence. To express it in one's art is what O'Hara and Hartigan did. There is the miracle of the everyday minor experience that is articulated and crystalized in O'Hara (one of his poems is called Having a Coke With You). He and Hartigan were unafraid to admit the variety in life. I believe that's him in the right side of the painting, about to walk through the dizzying cityscape that was, and still is, Manhattan.

Hartigan, a protean figure on the art scene, was viewed as a forerunner of Pop Art in her integration of everyday images in the midst of her abstract expressionism. At first, she started showing her work under the name "George Hartigan." She would say it was out of her respect for writer Georges Sand. She thought that being presented as a man who make people take her work more seriously. Thanks to Hartigan and others, that is no longer a problem.

Posted by Howard on December 23, 2008 in American Art Elsewhere, American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (2)

Recent Comments