|

|

Dallas, TX

Health Consultation

Former W.R. Grace & Company/Texas Vermiculite Site

2651 Manila Road

Dallas, Dallas County, Texas

EPA Facility Identification Number: TX0000605352

September 22, 2005

Prepared by:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

Division of Health Assessment and Consultation

Foreword: ATSDR's National Asbestos Exposure Review

Vermiculite, a naturally occurring mineral, was mined and processed in Libby, Montana, from the early 1920s until 1990. We now know that this vermiculite, which was shipped to many locations around the United States for processing, contained asbestos.

The National Asbestos Exposure Review (NAER) is a project of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). ATSDR is working with local, state, and federal environmental and public health agencies to evaluate public health impacts at sites that processed Libby vermiculite.

The evaluations focus on the processing sites and on human health effects that might be associated with possible past, current, or future exposure to asbestos from processing operations. Determining the extent and the hazard potential of commercial or consumer use of products such as vermiculite attic insulation or vermiculite gardening products made with contaminated vermiculite is outside the scope of this project. Information for consumers of vermiculite products has been developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), ATSDR, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

The sites that processed Libby vermiculite will be evaluated by (1) identifying ways people could have been exposed to asbestos in the past and ways that people could be exposed now and (2) determining whether the exposures represent a public health hazard. ATSDR will use the information gained from the site-specific investigations to recommend further public health actions as needed. Site evaluations are progressing in two phases.

Phase 1: ATSDR has selected 28 sites for the first phase of reviews based on the following criteria.

- EPA mandated further action at the site based upon contamination in place - or -

- The site was an exfoliation facility that processed more than 100,000 tons of vermiculite from the Libby mine. Exfoliation, a processing method in which vermiculite is heated and "popped," is expected to have released more asbestos than other processing methods.

The following document is one of the site-specific health consultations ATSDR and its state health partners are developing for each of the 28 Phase 1 sites. A future report will summarize findings at the Phase 1 sites and include recommendations for evaluating more than 200 other sites nationwide that received Libby vermiculite.

Phase 2: ATSDR will continue to evaluate former Libby vermiculite processing sites in accordance with the findings and recommendations contained in the summary report. ATSDR will also identify further actions as necessary to protect public health.

Executive Summary

ATSDR evaluated the W.R. Grace/Texas Vermiculite site (Dallas facility) because more than 396,900 tons of asbestos-contaminated vermiculite were shipped to that location and a facility at the site expanded vermiculite using the exfoliation process. Commercial exfoliation of vermiculite is a process of heating uniformly graded pieces of vermiculite in a furnace to expand or "pop" it into lightweight nuggets.

The Dallas facility operated from 1953 to 1992. The buildings on the site were demolished at some time during 2001 or 2002. The site currently consists of approximately 4 acres of vacant land in the Dallas metropolitan area. Although commercial and light industrial properties border the site, a residential area is located 1/4 mile to the north. 1990 census data indicate that 7,140 people lived within 1 mile of the site during the final decade of vermiculite processing.

While the facility was operating, workers at the facility and members of their households were exposed to asbestos from the processing and handling of asbestos-contaminated vermiculite and waste rock. Sufficient site- and process-specific information is available to consider these exposures a public health hazard. On the basis of the information available, ATSDR estimates that from 200 to 450 former workers were exposed during the time the plant operated.

Community members who lived or worked near the Dallas facility in the past could have been exposed to Libby asbestos in a variety of ways. Very little information is available to verify community exposure or to quantify the magnitude, frequency, or duration of any exposure. The two potential pathways of greatest concern are (1) plant emissions of Libby asbestos that may have reached the downwind residential area from 1953 to 1973 (before emission control equipment was installed) and (2) stockpiles of waste rock at the site that may have been accessible to community members, especially children. Children who were exposed to asbestos are a particularly sensitive population because asbestos-related health effects have a long latency period and children who are exposed would have more years to develop problems.

Most community members who live or work near the site now are not being exposed to asbestos from the site. The primary community exposure pathways that existed while the facility was operating, such as exposure from plant emissions and from contact with piles of vermiculite and waste rock on the site, have been eliminated. In the past, community members or workers may have taken waste rock off the site to use as fill material, driveway surfacing, or as a soil amendment. Not enough information is available to determine whether some individuals may be exposed to Libby asbestos through direct contact with waste rock taken from the site.

Exposure to asbestos does not necessarily mean an individual will get sick. The frequency, duration, and intensity of the exposure, along with personal risk factors such as smoking, history of lung disease, and genetic susceptibility determine the actual risk for an individual. The mineralogy and size of the asbestos fibers involved in the exposure are also important in determining the likelihood and the nature of potential health impacts. Because of existing data gaps and limitations in the science related to the type of asbestos at these sites, the risk of current or future health impacts for exposed populations is difficult to quantify.

At this site, where little can be done about past exposure and possible health effects relating to exposure, promoting awareness and offering health education to exposed and potentially exposed populations is an important intervention strategy. Health messages should be structured to facilitate self-identification and to encourage exposed individuals to either inform their regular physician or consult a physician with expertise in asbestos-related lung disease. Health care provider education in these communities would facilitate surveillance and improved recognition of nonoccupational risk factors that can contribute to asbestos-related diseases.

Background

ATSDR evaluated the W.R. Grace/Texas Vermiculite site (Dallas facility) because a large amount of vermiculite contaminated with amphibole asbestos was processed at the site by exfoliation. Based on available invoice data, the facility received more than 396,900 tons of vermiculite between 1967 and 1992 (EPA, unpublished data, 2001). Although some of the vermiculite may have been routed through Dallas for exfoliation elsewhere, much of it was probably exfoliated at the Dallas facility.

The Texas Vermiculite Company may have started processing vermiculite at the site as early as 1953, when they acquired the lease to the property [1]. In 1975, the Texas Vermiculite Company merged with W.R. Grace and Company (W.R. Grace) and vermiculite exfoliation continued at the site until 1992. The site reportedly remained vacant after 1992 when vermiculite processing ceased [1]. In 1996 and 1997, a contractor hired by W.R. Grace removed the processing equipment and cleaned up the site [1, 2]. Between May 2001 and September 2002, W.R. Grace demolished the on-site buildings.

W.R. Grace has owned the eastern 1.7 acres of the site, where the vermiculite processing buildings and storage structures once stood, since 1988 [1, 3]. The rest of the original 4 acre site is currently owned by the Kansas City Southern Railroad Company [3]. A brief chronology of site ownership and site activities is outlined in Table 1.

| Date | Site ownership and site activities |

|---|---|

| 1950 | Perlite Products leased 4 acres of land from Gulf, Colorado and Sante Fe Railroad. |

| 1953 | Perlite Products assigned the lease to Texas Vermiculite Company. |

| 1975 | Texas Vermiculite Company merged into W.R. Grace. |

| November 1988 | W.R. Grace purchased the 1.715-acre tract containing the former processing buildings. Their lease on the remainder of the original 4 acres was terminated. |

| 1992 | Exfoliation operations ceased at the site and the buildings remain unused until they are demolished sometime in 2001 or 2002. |

| 1996-1997 | W.R. Grace hired Phillip Environmental Services Corporation to remove the exfoliation processing equipment and clean up the site. |

| 2000-2001 | EPA conducted site visits and environmental sampling. |

| 2002 | ATSDR and EPA conducted a site visit. |

Source: Information in this table came from various sources, and the references for them are cited in the text of this report.

In the past, the Dallas facility produced a number of horticultural products for commercial growers and private consumers, including soil mixtures containing expanded (exfoliated) vermiculite (Jiffy Mix, Metro Mix, Redi-Earth, Terra-Lite Redi-Earth), pure expanded vermiculite (Terra-Lite, Terra-Lite Vermiculite), and expanded perlite (Perl-Gro, Terra-Lite Perlite). Among the building products containing vermiculite manufactured at the Dallas facility for commercial use were spray-applied fireproofing (Spatterkote, Zonolite Z-105, Monokote 3, 4, and 5) and various concrete aggregate products (EPA, unpublished data). The Monokote 3 fireproofing product was formulated with 10% to 19% chrysotile asbestos as an additive; Monokote 3 production was discontinued at the Dallas facility by July 5, 1973 (EPA, unpublished data).

Site Description

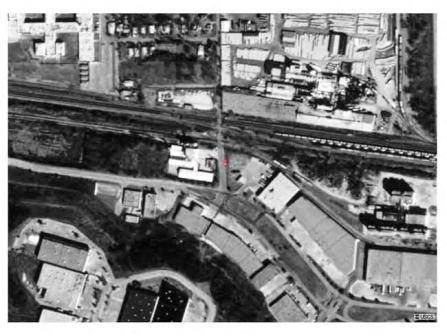

The Dallas, Texas, facility is located at 2651 Manila Road, on the west side of Dallas (Figures 1-3). The site consists of approximately 4 acres of land. The Texas Vermiculite Company and W.R. Grace & Company (W.R. Grace) conducted vermiculite exfoliation operations on the site from 1953 to 1992.

The processing buildings were located on the eastern 1.7 acre portion of the site [4]. This area currently consists of an open lot (i.e., no buildings or other structures are on the site) encircled by a 6-foot high chain link security fence [5]. Bare soil covers the area where the buildings were, but much of the area that surrounded the buildings is covered with grass and other vegetation [5]. The rest of the original 4 acre site is heavily vegetated with trees and ground cover and is accessible to the public [4, 5].

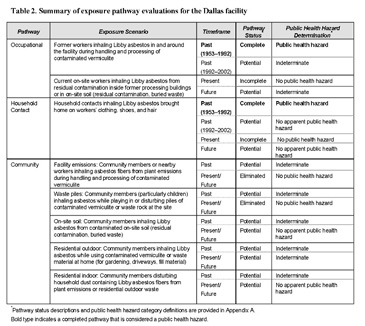

Current land use for the area around the site is a mixture of commercial, industrial, and residential. Historical aerial photographs indicate most of the commercial properties within 1/4 mile to the east and south of the site were developed between 1970 and 1984 [4]. A residential area located approximately 1/4 mile north of the site is visible in aerial photographs dating back to 1942; a school in this same area appears to have been constructed between 1942 and 1958 [4]. U.S. Census records for census tracts within several miles of the site indicate that more than 75% of the homes in the area were constructed before 1970 [6]. The majority of current householders within each of these census tracts moved into their current home in the 1980s and 1990s [6]. A total of 7,140 people lived within 1 mile of the site, according to 1990 census data (Figure 1).

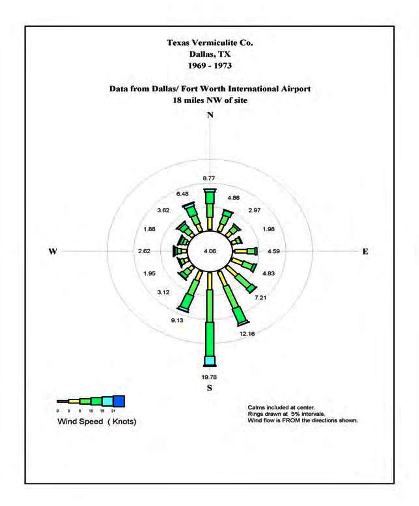

The National Weather Service characterizes the climate in Dallas as humid subtropical, with hot summers and a wide annual temperature range (average low of 33 degrees Fahrenheit in January, average high of 96 degrees Fahrenheit in July). While precipitation totals vary from less than 20 inches to more than 50 inches per year, the mean annual precipitation is 33.7 inches [7]. A large part of the annual rainfall results from thunderstorm activity. Snowfall is rare. Meteorological data from the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport suggest that the predominant wind direction for the area is from the south (Figure 4). The airport is 18 miles northwest of the site, therefore actual conditions at the site could vary due to local topography and other factors.

Vermiculite exfoliation

The U.S. Geological Survey describes vermiculite as "… a general term applied to a group of platy minerals that form from the weathering of micas by ground water. Their distinctive characteristic is a prominent accordion-like unfolding and expansion when heated … the [expanded] vermiculite material is very lightweight and possesses fire- and sound-insulating properties. It is thus well suited for many commercial applications."[8]

The1 vermiculite ore mined in Libby, Montana, was concentrated and milled to produce different sizes, or grades, of vermiculite. This milled vermiculite was then shipped to the Dallas facility and to other processing facilities throughout the country. Before milling, the raw vermiculite from the Libby mine contained up to 26% asbestos [9]. The various grades of milled vermiculite shipped from Libby contained fibrous amphibole asbestos at concentrations ranging from 0.3% to 7.0% [9].

Commercial exfoliation of vermiculite is a process that can be likened to popping popcorn. Vermiculite is heated in a furnace to temperatures of 1,500 degrees to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. As water molecules within the mineral structure are driven off, the vermiculite expands into lightweight, accordionlike nuggets (Figure 5) [8]. The unpopped material that remains after the vermiculite is expanded is called waste rock or stoner rock (Figure 6). Estimates of the asbestos content of the waste rock vary from 2% to 10% (EPA, unpublished data; J. Kelly, Minnesota Department of Health, personal communication, 2002).

In general, vermiculite exfoliation facilities were small-scale operations employing fewer than 50 people. Vermiculite was often delivered to the facilities in bulk by railcar. Workers at the exfoliation facilities used shovels or front-end loaders to manually unload vermiculite from the railcars and store it on the site in open stockpiles or enclosed silos. At many of the facilities, the transfer processes were later automated with screw-type augers and conveyor belts to deliver vermiculite to the storage areas and into the exfoliation furnace. Other manual tasks at these facilities included filling and sealing product bags, adding bags of vermiculite and chrysotile asbestos to the Monokote mixer, managing waste rock (filling bags or transferring bulk material), equipment maintenance, and general housekeeping.

Several equipment and operational changes were implemented at vermiculite exfoliation facilities in response to environmental and worker regulations promulgated throughout the 1970s. Although asbestos emissions from these exfoliation facilities were not regulated under 1970 EPA Clean Air Act amendments, W.R. Grace submitted information to EPA in May of 1973 indicating that 19 of their 31 exfoliation facilities had particulate and asbestos emission control equipment that was compliant with the regulations (EPA, unpublished data). As the OSHA permissible exposure level (PEL) for occupational exposure to asbestos steadily decreased from an initial standard of 12 fibers per cubic centimeter of air (f/cc) established in 1971 to the 1994 standard of 0.1 f/cc [10], W.R. Grace initiated employee monitoring and various process design changes to achieve compliance with the OSHA regulations (EPA, unpublished data).

At some exfoliation facilities, respiratory protection (e.g., dust masks, various types of respirators) was periodically documented for certain job categories in industrial hygiene reports dating back to the early 1970s (EPA, unpublished data). Information is not available to evaluate the use or effectiveness of this respiratory equipment in reducing workers' exposure to asbestos. The overall effectiveness depends on a number of factors, including the protection factor of the masks, the effectiveness of the fit testing protocols, and the actual compliance of individuals required to wear the masks. In 1977, W.R. Grace initiated an internal communication program intended to enforce respirator use and provide education to workers regarding the health impacts of smoking combined with asbestos exposure (EPA, unpublished data). The increased risk of lung cancer from smoking combined with asbestos exposure is stated as the basis for an employee "no smoking" policy found in the 1982 W.R. Grace employee handbook (EPA, unpublished data).

Records indicate waste rock and fine particulates from the dust and fiber control equipment at many of the exfoliation facilities was bagged and disposed of at local landfills beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s (EPA, unpublished data)[11]. Prior to that, very little information is available to track the handling and disposal of waste rock and fine particulates at these facilities. Anecdotal reports indicate the waste rock at some facilities was temporarily stockpiled at the site, these stockpiles were accessible to the public, and children played in them [12, 13]. At one exfoliation facility, workers and nearby community members were encouraged to take waste rock home for personal use [12].

Asbestos and asbestos-related health effects

Asbestos minerals fall into two groups, serpentine and amphibole. Serpentine asbestos has relatively long and flexible crystalline fibers; this class includes chrysotile, the predominant type of asbestos used commercially. Fibrous amphibole minerals are brittle and have a rod- or needle-like shape. Amphibole minerals regulated as asbestos by OSHA include five classes: crocidolite, amosite, and the fibrous forms of tremolite, actinolite, and anthophyllite. Other unregulated amphibole minerals, including winchite, richterite, and others, can also exhibit fibrous asbestiform properties [8].

Vermiculite from Libby was found to contain several types of asbestos fibers including the amphibole asbestos varieties tremolite and actinolite and the related fibrous asbestiform minerals winchite, richterite, and ferro-edenite [8]. In this report, the terms Libby asbestos and amphibole asbestos will be used to refer to the characteristic composition of asbestos contaminating the Libby vermiculite.

Individual asbestos fibers are too small to be seen without a microscope or other laboratory instruments. However, asbestos can sometimes be visible when many fibers form together in "bundles" or when the asbestos forms in nonfibrous blocky fragments (Figure 6). Asbestos fibers do not have any detectable odor or taste. They do not dissolve in water or evaporate into the air, although individual asbestos fibers can easily be suspended in the air. Asbestos fibers do not move through soil. They are resistant to heat, fire, and chemical and biological degradation. As such, they can remain virtually unchanged in the environment over long periods of time [14].

Appendix B provides an overview of several concepts relevant to the evaluation of asbestos exposure, including analytical techniques and federal regulations concerning asbestos.

In terms of human exposure, ATSDR considers the inhalation route of exposure to be the most significant in the current evaluation of sites that received vermiculite from Libby. Although ingestion and dermal exposures routes may exist, health risks from these exposures are very low compared to health risks from the inhalation route [14]. Health effects associated with breathing asbestos include the following:

- Malignant mesothelioma-Cancer of the membrane (pleura) that encases the lungs and lines the chest cavity. This cancer can spread to tissues surrounding the lungs or other organs. The majority of mesothelioma cases are attributable to asbestos exposure [14].

- Lung cancer-Cancer of the lung tissue, also known as bronchogenic carcinoma. The exact mechanism relating asbestos exposure with lung cancer is not completely understood. The combination of tobacco smoking and asbestos exposure greatly increases the risk of developing lung cancer [14].

- Noncancer effects-these include asbestosis (scarring of the lung and reduced lung function caused by asbestos fibers lodged in the lung); pleural plaques (localized or diffuse areas of thickening of the pleura); pleural thickening (extensive thickening of the pleura which may restrict breathing); pleural calcification (calcium deposition on pleural areas thickened from chronic inflammation and scarring); and pleural effusions (fluid buildup in the pleural space between the lungs and the chest cavity) [14].

Numerous studies of occupationally exposed workers conclusively demonstrate that inhalation of asbestos can increase the risk of mesothelioma, lung cancer, and various noncancer health effects [14]. Several studies have documented health impacts consistent with asbestos-related disease in workers and others associated with the Libby mine [15-20]. Asbestos-related health impacts to workers associated with vermiculite exfoliation facilities have also been documented [21, 22].

Exposure to asbestos does not necessarily mean an individual will get sick. The frequency, duration, and intensity of the exposure, along with personal risk factors such as smoking, history of lung disease, and genetic susceptibility determine the actual risk for an individual [14]. The mineralogy and size of the asbestos fibers involved in the exposure are also important in determining the likelihood and the nature of potential health impacts. Exposure to amphibole asbestos fibers that are long (greater than 10 micrometers) increases the risk of carcinogenic health effects such as mesothelioma and lung cancer [14, 23, 24]. Short amphibole fibers (less than 5 micrometers) are thought to be less important in inducing carcinogenic effects, but they may play a role in increasing the risk of noncancer effects such as asbestosis [25]. The fibrous forms of amphibole asbestos are potentially more toxic than the commonly encountered serpentine fibers (chrysotile) [14, 24, 26].

Chronic exposure is a significant risk factor for asbestos-related disease. However, brief episodic exposures may also contribute to disease. A brief, high intensity exposure from working just two summers at a vermiculite exfoliation facility in California has been linked to a case of fatal asbestosis [22]. Very little conclusive evidence is available regarding the health effects of low dose, intermittent exposures to asbestos. A "safe" exposure level below which health effects are unlikely has yet to be formally defined in federal regulations and policies.

Methods

Data sources

ATSDR obtained site-specific environmental sampling and facility operational data from either EPA or W.R. Grace, the company that formerly owned the Libby mine and many of the exfoliation sites around the country. Current environmental data for the site consisted of indoor air and dust, outdoor soil, and bulk material sampling results from EPA's site investigation in 2001[27].

EPA assembled and summarized W.R. Grace invoices for shipments of vermiculite from the Libby mine to vermiculite sites across the country. These invoice records corresponded to the period of W.R. Grace's ownership of the Libby mine, which began in 1963. Limited information was available about production and shipping of vermiculite prior to 1964. ATSDR used EPA's summary of invoices to estimate vermiculite tonnage figures for the Dallas facility (EPA, unpublished data, April 2001).

ATSDR acquired historical industrial hygiene data, including personal air samples for workers and engineering sampling data from work areas, and various operational and technical data for the Dallas site from a database of W.R. Grace documents. EPA obtained this document database, comprised of approximately 2.5 million electronic image files, during the investigation of the Libby mine. The database contains confidential business information as well as private information that is not available to the public.

ATSDR obtained several site-specific documents from W.R. Grace containing historical operational and environmental data. These data consisted of industrial hygiene reports, confirmation air samples collected by W.R. Grace after they had closed and cleaned the site, and information concerning waste disposal. Other sources of data used for evaluating the site include U.S. Census data, aerial photographs, and site visits by ATSDR and EPA.

Site evaluation methodology

The site evaluation consisted of (1) identifying and assessing complete or potential exposure pathways to Libby asbestos for the past, present, and future and (2) determining whether the exposure pathways represent a public health hazard. The latter determination is qualitative or semiquantitative at best due to a number of underlying limitations, including difficulties in quantifying asbestos exposures, assessing asbestos toxicity, and quantifying risks for carcinogenic and noncarcinogenic health endpoints. A more rigorous, quantitative approach of evaluating actual or assumed exposures based on calculating the risk of potential health impacts was not possible given the limitations in available data.

Using knowledge gained from investigations in Libby, Montana, and at a few early investigations at vermiculite exfoliation facilities, ATSDR identified several likely pathways for occupational and community exposure to asbestos at vermiculite exfoliation facilities (Appendix C). As stated previously, ATSDR considered only the inhalation route of exposure at the Phase 1 sites .

An exposure pathway consists of five elements: a source of contamination; a medium through which the contaminant is transported; a point of exposure where people can come into contact with the contaminant; a route of exposure by which the contaminant enters or contacts the body; and a receptor population. A pathway is considered complete only if all five elements are present and connected. More information on exposure pathways is included in Appendix A.

To determine whether complete or potential exposure pathways pose a public health hazard, ATSDR considered available site-specific exposure data (e.g., the frequency, duration, and intensity of exposure). Although a few risk-based metrics are available to evaluate levels of airborne asbestos, no health-based comparison values are available to indicate "safe" levels of asbestos in air, soil, dust, or other bulk materials such as vermiculite and waste rock. In addition, very little information is available about the health risks associated with low dose, intermittent exposures to amphibole asbestos. These limitations necessitate that ATSDR use a conservative approach to public health decisionmaking for the site.

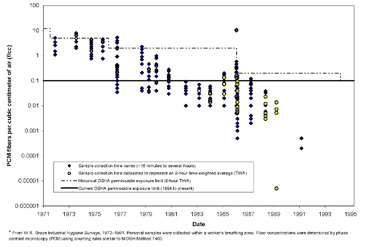

For asbestos fiber levels in air, ATSDR used the current risk-based Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) permissible exposure limit (PEL) of 0.1 fibers per cubic centimeter (f/cc) of air as one metric to assess asbestos inhalation exposure for workers [10]. The 0.1 f/cc OSHA PEL, calculated as an 8-hour time-weighted average, represents the upper limit of exposure for a worker during a normal work day. It is worthwhile to note that OSHA's final rules for occupational exposure to asbestos acknowledged that "…a significant risk remains at the PEL of 0.1 f/cc" [10]. Instead of reducing the PEL even further, OSHA elected to eliminate or reduce this risk through mandated work practices, including engineering controls and respiratory protection for various classifications of asbestos-related construction activities [10].

ATSDR acknowledges two community exposure guidelines for airborne asbestos established by interagency workgroups following the World Trade Center collapse in 2001. For short-term (less than 1 year) exposures, 0.01 f/cc asbestos in indoor air was developed as an acceptable reoccupation level for occupants of residential buildings [28]. A risk-based comparison value of 0.0009 f/cc for asbestos in indoor air was developed to be protective under long-term residential exposure scenarios [29]. All three exposure values (i.e., the OSHA PEL, the two World Trade Center community guidance values) are primarily applicable to airborne chrysotile asbestos fibers that have lower toxicity than amphibole asbestos.

In the absence of any health- or risk-based comparison levels for asbestos in soil, dust, or bulk materials, ATSDR is evaluating these exposure pathways qualitatively, with strong consideration given to known or potential exposure scenarios at each site. For example, to determine whether asbestos in soil poses a public health hazard at a site, ATSDR is considering the concentration of asbestos in the soil, the horizontal extent of asbestos-contaminated surface areas, the presence or absence of ground cover, the frequency and type of activities that disturb soil, and accessibility. Soil containing Libby asbestos at levels equal to or greater than 1% is generally considered a health hazard requiring remediation. Depending on site-specific exposure scenarios, remediation or other measures may also be appropriate to prevent exposure to soil containing less than 1% Libby asbestos. Federal standards regulate materials that contain more than 1% asbestos [30, 31]; therefore, the 1% level has been used as an action level for soil remediation activities at a number of sites. EPA and ATSDR recognize that this 1% standard is not derived from a risk assessment or any other type of health-based analysis; therefore, it does not ensure that airborne asbestos fibers resuspended by disturbing these soils will be below levels protective of human health [32]. In fact, recent activity-based studies have shown that disturbing soil containing less than 1% Libby asbestos can resuspend fibers and generate airborne concentrations at or near the OSHA permissible exposure limit [33, 34].

Results

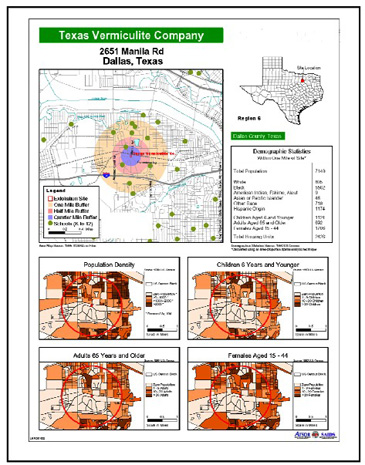

A summary of the exposure pathway evaluations for the Dallas site is presented in Table 2. The findings for each of the pathways are presented in the following paragraphs.

Table 2 Printer-friendly version (PDF, 43 KB)

Occupational pathway (past: 1953-1992 timeframe)

The occupational exposure pathway for former workers exposed to airborne Libby asbestos in and around the facility during handling and processing of vermiculite from 1953 to 1992 is considered complete. On the basis of available information concerning the intensity, frequency, and duration of past occupational exposures, this exposure pathway is considered a public health hazard.

Personal sampling results for workers at the facility indicate airborne fiber levels consistently in the range of 0.1 f/cc to 10 f/cc throughout the 1970s (Figure 7). In the 1980s, personal sampling results are predominantly below 0.1 f/cc, although some higher concentrations were documented in 1985 and 1986. Area sampling data available from 1972 to 1991 exhibit the same trend of decreasing airborne fiber levels (Figure 8). Personal samples, typically collected within a worker's breathing zone, were associated with specific workers. Most of the area sampling was conducted at consistent locations in the exfoliation process where fibers were likely to be released (e.g., the furnace baghouse, the furnace stoner deck where waste rock and expanded product were separated, the waste rock hopper) (EPA, unpublished data). Sample collection time varied from 15 minutes to several hours; some sample results are adjusted to represent 8-hour time-weighted averages (Figure 7).

Although no sampling data are available from 1953 to 1971, airborne fiber levels during this period were probably in the same range or higher than the levels documented in 1972 and 1973 (1 f/cc to 10 f/cc). Measured airborne fiber levels within the Dallas facility decreased throughout the 1970s as a result of W.R. Grace's efforts to comply with federal OSHA regulations promulgated in 1971 to protect workers from occupational exposure to asbestos (EPA, unpublished data). Asbestos exposure levels for workers could have been much higher in the 1950s and 1960s prior to OSHA regulations. Asbestos exposures would also be higher for workers who manually performed some of the material handling processes, such as unloading vermiculite deliveries from railcars, transferring vermiculite into furnace hoppers, and transferring bulk quantities of waste rock.

The MK-3 fireproofing product manufactured at the Dallas facility contained 10% to 19% chrysotile as an ingredient (EPA, unpublished data). MK-3 also contained vermiculite. Workers involved in mixing and packaging MK-3 may have been exposed to higher levels of airborne asbestos because they handled both chrysotile and amphibole asbestos-contaminated vermiculite.

The frequency and duration of former worker exposures varied depending on their job assignment, facility operation schedule, and period of employment. The Dallas facility exfoliated vermiculite 24 hours a day (in three 8-hour shifts), 5 days a week (EPA, unpublished data). The facility reportedly employed 38 people in 1980 and 42 people in 1987 (EPA, unpublished data). The length of employment for workers at the Dallas facility is unknown, although several employees were listed in the industrial hygiene survey reports for more than 10 consecutive years (EPA, unpublished data). Workers appeared to perform the same job assignment throughout the day, such as bagging product, operating the furnace, driving a forklift, or cleaning up (EPA, unpublished data).

W.R. Grace had a respiratory protection program for the Dallas facility as early as 1972. Industrial hygiene reports from the 1970s to 1991 periodically documented some workers wearing disposable, filtering face piece dust masks (3M 8710 model) (EPA, unpublished data). Additionally, a dust survey conducted by W.R. Grace in 1972 indicated the Dustfoe 77 mask was used by workers while mixing Monokote 3, which contained 10% to 19% chrysotile as an additive (EPA, unpublished data). Information is not available to evaluate the overall effectiveness of this respiratory equipment in reducing worker exposures to asbestos. The overall effectiveness depends on several factors, including the protection factor of the masks, the effectiveness of the fit testing protocols, and the actual compliance of individuals required to wear the masks.

Although most personal and area sampling data are associated with specific process operations, Libby asbestos fibers were released into the facility air throughout the workday during vermiculite processing and handling. From 1979 to 1981, airborne fibers were detected in two of four 30-minute area samples collected in the employee lunchroom (0.57 f/cc in February 1979, 0.14 f/cc in March 1981). In 1975, a 15-minute area sample identified as "general atmosphere - furnace room" indicated 37.62 f/cc in the air. In 1979, a 50-minute sample collected in the office area indicated 0.27 f/cc in the air (EPA, unpublished data)

Workers could have been exposed to Libby asbestos outside the facility as well. Fugitive emissions from loading, unloading, or transferring bulk vermiculite or waste rock resulted in outdoor airborne asbestos fiber releases. Information provided to EPA in 1978 by a company that exfoliated Libby vermiculite indicated airborne fiber levels were as high as 245 f/cc in the unloading area where unexpanded vermiculite was dumped from rail cars [35]. Stack emissions from the furnaces and the Monokote mixer also contributed to outdoor fiber releases. W.R. Grace indicated they had particulate and asbestos control equipment on the Dallas process stacks by May 1973 (EPA, unpublished data). The concentrations of airborne asbestos fibers in outdoor air around the facility due to fugitive and stack emissions were likely much higher before this control equipment was installed.

Various non-W.R. Grace workers probably visited the Dallas facility periodically to haul waste rock away from the facility, purchase products, pick up products for delivery, or provide services (e.g., construction and electrical services, equipment maintenance). Data available from other facilities indicate that waste haulers may have been exposed to asbestos as they loaded and unloaded waste rock (EPA, unpublished data). At the Dallas facility, 18 building permits were issued from 1956 to 1989 to construct new buildings, build additions to existing structures, and install a variety of fuel storage tanks at the site [36]; these activities likely resulted in construction workers being exposed to asbestos at the site.

The non-W.R. Grace workers on the site may have been exposed to airborne asbestos in and around the Dallas facility, but the frequency and duration of the exposure was likely very low. The intensity, frequency, and duration of the exposure to waste haulers and construction workers may have been higher than the exposure of other non-W.R. Grace workers. All of these on-site workers were exposed much less frequently and for much shorter durations than the full-time workers at the W.R. Grace facility.

Occupational pathway (past: 1992-2002 timeframe)

The site has not been used since 1992. The only workers on the site from 1992 to 2002 were the W.R. Grace contractors who cleaned the site in 1996 and 1997 and those who demolished the buildings in 2001 and 2002. These workers may have been exposed to asbestos at the site; the exposure pathway is potentially complete. Because the intensity, frequency, and duration of these workers' exposure to asbestos is not known, this exposure pathway is considered an indeterminate public health hazard.

W.R. Grace stopped exfoliating vermiculite at the Dallas facility in 1992. From 1992 until 1996, the facility was unused and partially fenced [1]. From June 1996 to June 1997, Phillip Environmental Services (PESC) cleaned certain areas of the facility (e.g., removed debris, cleaned equipment prior to removal), removed the process equipment, and performed a final cleanup of the interior building areas [2]. A total of 40 cubic yards of waste was generated and disposed of as nonhazardous waste; the disposal facility was not specified [2]. Health and safety measures used for the PESC workers during these operations cannot be ascertained from the PESC summary report. Because these workers cleaned and removed process equipment, including baghouse filters and exfoliation furnaces, they could have been exposed to high levels of airborne asbestos if they did not use appropriate respiratory protection and decontamination methods. Although the site cleanup was documented as lasting a full year, exposure to workers would have occurred only during actual cleanup activities.

Following the facility cleanup, W.R. Grace collected three air samples inside the buildings. Insufficient information is available to determine if aggressive sampling was performed (e.g., whether air and dust surrounding the sample pump was disturbed to resuspend any residual fibers during sampling). Laboratory sample results indicated less than 0.0011 f/cc at each sample location (EPA, unpublished data).

EPA Region 6 conducted site visits in 2000 and 2001 and collected environmental samples at the Dallas site in 2001. Environmental samples consisted of 4 dust samples from surfaces inside the former processing building, 5 bulk samples of residual material inside the former processing building, and 11 surface soil samples from various on-site and off-site locations [27].

No asbestos structures were detected in three of the dust samples. A single asbestos structure was detected in the fourth dust sample; the calculated concentration corresponding to this detection was stated as less than 158,690 structures per square centimeter. Asbestos was detected in 1 of the 5 samples of residual or bulk materials collected inside the buildings; the sample concentration was reported as 2% tremolite. Asbestos was detected at trace levels (less than 1%) in 4 of the 8 on-site soil samples. The trace levels of asbestos were on the north side of the property, along the railroad spur formerly used to deliver vermiculite to the facility.

W.R. Grace demolished the on-site buildings in 2001 and 2002. ATSDR has no information concerning health and safety measures used for the construction workers during these operations.

Occupational pathway (present/future timeframe)

The site is not being used, therefore the exposure pathway for current on-site workers is incomplete and poses no public health hazard. The pathway concerning future worker exposure to residual contamination at the site is considered potentially complete because trace levels of Libby asbestos were detected in some areas of surface soil. Subsurface soils may also contain Libby asbestos. This exposure pathway is considered an indeterminate public health hazard.

Surface soil samples collected in 2001 by EPA indicated trace (<1%) levels of asbestos on the northern side of the property, along the railroad spur. Subsurface soil sampling has not been performed to determine whether waste materials are buried on the site. Historical aerial photographs available from 1942 to 2001 (approximately 1 photograph per decade) do not indicate any obvious areas of on-site waste disposal. Company records indicate that asbestos-contaminated waste from the Dallas facility was disposed of at the City of Dallas McComus [McCommas] Landfill beginning as early as 1979 [11].

Household contact pathway (past: 1953-1992 timeframe)

Exposure of household contacts to airborne Libby asbestos unintentially brought home on the clothing, shoes, and hair of former workers is considered a complete exposure pathway that represented a public health hazard. Although exposure data are not available for household contacts, their exposures are inferred from documented former worker exposures and facility conditions that did not prevent contaminants being brought into the workers' homes.

Vermiculite exfoliation was reportedly a very dusty operation. The workers in the facility did not wear uniforms (EPA, unpublished data). Although on-site laundering facilities were considered in 1984, they were not implemented due to union disputes (EPA, unpublished data). Members of the households of former W.R. Grace workers were exposed to Libby asbestos fibers brought home on the workers' clothing, shoes, and hair if the workers did not shower or change clothes before leaving work. Family members or other household contacts could have been exposed to asbestos by direct contact with the worker or by laundering clothing. These exposures cannot be quantified without information concerning the levels of asbestos on the workers' clothing and behavior-specific factors (e.g., worker practices, household laundering practices). However, exposure to asbestos resulting in asbestos-related disease in family members of asbestos industry workers has been well-documented [37, 38].

Household contact pathway (past: 1992-2002 timeframe)

Several groups of recent on-site workers (during 1996-1997 and 2001-2002 site activities) may have been exposed to Libby asbestos from the site. These workers likely brought home very low concentrations of asbestos over a relatively short period of time. This exposure is considered no apparent public health hazard for household members who had contact with the workers or the workers' clothing.

Household contact pathway (present/future timeframe)

The site is currently vacant; therefore current exposure pathways for on-site workers and their household contacts are incomplete and pose no public health hazard. Levels of asbestos brought home by future on-site workers will likely be very low and will be of relatively short duration. The exposure pathways for household contacts of future on-site workers is considered no apparent public health hazard.

Community pathways (past timeframe)

Community members who lived or worked around the Dallas facility from 1953 to 1992 could have been exposed to Libby asbestos from facility emissions, by disturbing or playing on on-site waste rock piles, by disturbing on-site soil, or from direct contact with waste rock brought home for personal use. Children exposed to asbestos are a particularly sensitive population because of the length of time the asbestos fibers remain in their lungs and the long latency period of asbestos-related diseases. Very little information is available to reconstruct the magnitude, frequency, or duration of these community exposures; therefore, they are considered an indeterminate public health hazard.

Community members and area workers could have been exposed to Libby asbestos fibers released into the ambient air from fugitive emissions or from furnace stack emissions generated while the facility was operating. The predominant wind direction is to the north (Figure 4), toward the residential area approximately 500 feet north of the Dallas facility (Figures 1-3). This residential area is documented in aerial photographs as early as 1942 [4]. These aerial photographs also indicate commercial properties constructed within 1/4 mile to the east and south of the site sometime between 1970 and 1984.

Fugitive emissions from loading, unloading, or transferring bulk vermiculite or waste rock resulted in airborne asbestos fiber releases in areas around the facility. Stack emissions from the furnaces and the Monokote mixer also contributed to outdoor fiber releases. W.R. Grace indicated they had particulate and asbestos control equipment on the Dallas process stacks by May 1973 (EPA, unpublished data). In 1975, a notice of violation was issued to Texas Vermiculite from the City of Dallas

Department of Public Health for exceeding the city's particulate emission standard [36]. The concentrations of airborne asbestos fibers in outdoor air around the facility due to fugitive and stack emissions were likely much higher prior to the 1970s. At an exfoliation facility in Weedsport, New York in 1970, stack test data for an exfoliation furnace without particulate control equipment indicated particulate emission rates of 6 pounds per hour (EPA, unpublished data). Particulates captured by the filters in the control equipment reportedly contained 1%-3% friable Libby asbestos (EPA, unpublished data).

The exposure pathway for community members (particularly children) playing in or otherwise disturbing on-site piles of contaminated vermiculite, waste rock, or on-site soil at the facility in the past is considered to be a potential exposure pathway. When the facility was operating, waste rock may have been temporarily stockpiled on the site and accessible to children and other community members. Anecdotal or photographic evidence of children playing in on-site waste piles is available for several similar exfoliation facilities [12, 13, 39]. After the Dallas facility closed down in 1992, the processing equipment remained on the site until 1996-1997 and the buildings were not dismantled until 2001 or 2002. Graffiti observed in photos of the interior and exterior of the former buildings indicates the presence of trespassers at the site before the buildings were demolished and the lot was securely fenced [40].

Community members' use of contaminated vermiculite or waste material at home is considered a potential exposure pathway. At a former vermiculite exfoliation facility in Minneapolis, Minnesota, waste rock was advertised as "free crushed rock," and community members took it home to use in their yards, gardens, and driveways [12]. Insufficient information is available to determine whether this happened at the Dallas facility during the time vermiculite was processed there. If so, people may have been exposed to airborne Libby asbestos by handling waste rock and working with it in their yards and gardens.

Libby asbestos fibers could have infiltrated homes surrounding the Dallas facility from plant emissions or from waste rock brought home for personal use. Insufficient information is available concerning the level of indoor residential contamination that may have resulted from past air emissions and community use of waste rock. Indoor residential exposure to Libby asbestos fibers in the past is an indeterminate public health hazard.

Community pathways (present/future timeframe)

Most community members who live or work near the site now are not being exposed to Libby asbestos from the site. Several community exposure pathways, such as exposure to ambient air emissions and exposure to on-site vermiculite and waste rock piles, have been eliminated and therefore pose no public health hazard to the current community. Potential pathways exist for exposure of individuals to contaminated soil or to waste rock brought home from the facility for personal use.

Currently, the areas of contaminated soil identified during EPA sampling pose no apparent public health hazard. ATSDR considers the waste rock exposure pathway an indeterminate public health hazard because not enough information is available to determine whether individuals brought waste rock home for personal use.

During the site visit in July 2002, ATSDR staff members noted that no waste piles were observed at the site [5]. The present and future exposure pathways to on-site waste piles iare considered eliminated and therefore pose no public health hazard to community members. Present and future exposure to Libby asbestos from facility air emissions also have been eliminated because the facility is no longer in operation.

Amphibole asbestos, characterized as tremolite, was detected at trace(<1%) levels in surface soils on the northern edge of the site, primarily along the former railroad spur used for delivering vermiculite to the site. These areas of on-site soil contamination are currently fenced and inaccessible to the public. Amphibole asbestos was also detected at trace levels in 1 of the 3 off-site soil samples collected in a residential area north of the site (downwind). The area where the off-site soil sample was collected is a grass-covered field. This ground cover would eliminate or reduce airborne dispersal of asbestos fibers from the soil, making exposure unlikely.

Not enough information is available to determine whether individuals are being exposed to Libby asbestos through direct contact with waste rock brought home for personal use, for example, as fill material, driveway surfacing, or as a soil amendment. Vermiculite or waste rock brought home from the facility in the past could still be a source of exposure today. If the asbestos-containing material is covered (e.g., with soil, grass, other vegetation) and is not disturbed, the asbestos fibers will not become airborne and will not pose a public health hazard. EPA did not find any evidence of asbestos-contaminated waste rock during a thorough visual inspection of residential and commercial properties adjacent to the site.

Facility emissions have ceased and are no longer a source of potential contamination in nearby homes. Residual Libby asbestos from potential past sources is possible, though housekeeping (particularly wet cleaning methods) over the past years would probably have removed any residual Libby asbestos in area homes. The only likely current source of Libby asbestos fibers in the home would be from waste rock brought home for residential use. Insufficient information is available to determine whether waste rock was used in the community. However, the waste rock alone would not be expected to contribute significantly to residential indoor exposure. Therefore, current and future residential indoor exposure pathways are considered no apparent public health hazard for community members.

Discussion

Exposure pathway evaluations

While the Dallas facility was operating, processing and handling of asbestos-contaminated vermiculite clearly resulted in asbestos exposure to former workers and their household contacts. Sufficient site- and process-specific information is available to consider these exposures a public health hazard. On the basis of available information, ATSDR estimates that from 200 to 450 former workers were exposed during the time the plant operated.

Community members who lived or worked near the Dallas facility in the past could have been exposed to Libby asbestos from facility emissions, by disturbing or playing on on-site waste rock piles, by disturbing on-site soil, or from direct contact with waste rock brought home for personal use. Very little information is available to verify these community exposures or to quantify their magnitude, frequency, or duration. They are therefore considered an indeterminate public health hazard. The two potential pathways of greatest concern are (1) plant emissions of Libby asbestos that may have reached the downwind residential area from 1953 to 1973 (before emission control equipment was installed) and (2) on-site waste rock piles that may have been accessible to community members, especially children. Children who were exposed to asbestos are a particularly sensitive population because of the length of time the asbestos fibers could remain in their lungs and the long latency period of asbestos-related diseases.

Most community members who live or work near the site now are not being exposed to Libby asbestos from the site. Several community exposure pathways that existed while the facility was operating, such as plant emissions and on-site vermiculite and waste rock piles, have been eliminated. EPA did not find any evidence of asbestos-contaminated waste rock during a thorough visual inspection of residential and commercial properties adjacent to the site. However, not enough information is available to determine whether some individuals may still be exposed to Libby asbestos through direct contact with waste rock taken from the site in the past to use in the community as fill material, driveway surfacing, or as a soil amendment.

Potential health impacts

Exposure to asbestos does not necessarily mean an individual will get sick. The frequency, duration, and intensity of the exposure, along with personal risk factors such as smoking, history of lung disease, and genetic susceptibility determine the actual risk for an individual. The mineralogy and size of the asbestos fibers involved in the exposure are also important in determining the likelihood and the nature of potential health impacts.

Given the limited or nonexistent exposure data available to characterize many of the pathways associated with Libby asbestos at the Dallas site, the risk of future health impacts for the exposed populations cannot be quantified. ATSDR is working with state health department partners across the United States to review historical health statistics for communities around many of the facilities that processed Libby vermiculite, including the Dallas facility. As this information is reviewed and validated, ATSDR's Division of Health Studies will release the findings of the health statistics reviews in a separate summary report.

Limitations

A number of site-specific limitations affect the exposure pathway evaluation and health risk characterization efforts at the Dallas site. Exposure data are not available for many of the past and current exposure pathways. This information may never be available for the past exposure scenarios. The available site-specific sampling results do not typically describe the mineralogy and fiber size distribution of the asbestos detected. This information is necessary to conduct a quantitative assessment of the actual toxicity and potential health impacts associated with exposure. Historical personal and area samples collected inside the Dallas facility and analyzed by phase contrast microscopy (PCM, see Appendix B) refer to measured fiber levels. However, fibers other than asbestos may have been counted in the sample analyses. PCM techniques alone cannot distinguish between asbestos fibers and nonasbestos fibers. PCM techniques also cannot detect very thin fibers (fibers that have diameters less than 0.25 micrometers (µm)).

Limitations in the current state of the science related to amphibole asbestos also influence the evaluation of exposure to Libby asbestos exposures and the potential for health risks associated with the exposure. Health-based comparison values representing "safe" levels of amphibole asbestos in air have not been developed. Determining "safe" levels of asbestos in other environmental media (soil or dust) is even more difficult because a safe level is not determined by the inherent asbestos fiber or mass concentration in the medium itself, but rather on the potential airborne fiber exposure associated with disturbing asbestos-contaminated soil or dust. Two options are available to estimate the resuspension of asbestos fibers from soil or dust into air during realistic exposure scenarios, but they are both relatively difficult and costly to implement. One option is to conduct site-specific field tests that directly measure airborne fiber levels during simulated exposure scenarios. The other option is to collect site-specific soil samples, analyze them in accordance with EPA 540/R/97/28 to obtain the fraction of fibers in the soil that can be released into the air, and then use this information in an appropriate air modeling effort to simulate exposure scenarios.

An adequate toxicological model to evaluate the noncarcinogenic health risks of amphibole asbestos exposure does not exist. The current EPA model used to quantify carcinogenic health risks due to asbestos exposure has significant limitations, including the fact that it does not consider mineralogy or fiber size distribution and it combines both lung cancer and mesothelioma risk into one slope factor. EPA is in the process of updating their asbestos risk methodologies. A draft model for quantifying carcinogenic health risks associated with amphibole asbestos has been developed, although it has not been formally accepted through the EPA review process [23]. This draft methodology requires detailed asbestos sample characterization beyond what was generated at these vermiculite sites. Data gaps in scientific research related to Libby asbestos have resulted in ongoing and largely unresolved discussions in the scientific community regarding the potential health risks of low-level, intermittent exposures and the relative importance of short asbestos fibers (fibers <5 micrometers in length) in noncancer health effects [25].

Additional considerations and limitations associated with asbestos-related evaluations are discussed in Appendix B.

Public health response

Most of the current and future exposure pathways associated with Libby asbestos at the Dallas site have been eliminated or do not pose a public health hazard. ATSDR characterized two exposure pathways as indeterminate health hazards: the potential use of waste rock in the community and the potential redevelopment of the site in the future. Insufficient information is available to characterize the asbestos exposures associated with these potential pathways. Providing awareness and information to the appropriate groups of people at the local level is an appropriate public health response at this time.

ATSDR characterized several historical exposure pathways as either confirmed or indeterminate public health hazards. Increased health risks due to past exposure to Libby asbestos are difficult to quantify, and actual asbestos-related health effects are difficult to treat. The latency period between asbestos exposure and disease can be 15 to 20 years or more. Asbestos-related diseases are not curable, though some treatments are available to ease the symptoms and perhaps slow disease progression. People who have been exposed to asbestos can take steps to control their risk or susceptibility, such as preventing additional exposure to asbestos and refraining from smoking.

At this site, where little can be done about past asbestos exposure or possible resulting health effects, promoting awareness and offering health education to exposed and potentially exposed populations is an important intervention strategy. For exposed individuals (e.g., former workers, their household contacts, and children who played in waste piles), health messages should be structured to facilitate self-identification and encourage individuals to either inform their regular physician of their asbestos exposure or consult a physician with expertise in asbestos-related lung disease. Health care provider education in these communities would facilitate improved surveillance and recognition of nonoccupational risk factors that can contribute to asbestos-related diseases.

Conclusions, recommendations, and public health action plan

Former workers and their household contacts (1953 to 1992)

People who worked at the W.R. Grace Dallas facility from 1953 to 1992 were exposed to airborne levels of Libby asbestos above current occupational standards. Repeated exposure to airborne Libby asbestos at these elevated levels increased a worker's risk for asbestos-related disease and therefore posed a public health hazard to former employees.

Members of the households of former workers may have been exposed to asbestos fibers if the workers did not shower or change clothes before leaving work. Although exposure data are not available for household contacts of former exfoliation workers, their exposures are inferred from documented worker exposure and facility conditions. This pathway therefore represents a public health hazard to members of the households of former workers.

Recommendations

- Promote awareness of past asbestos exposure among former workers and members of their households.

- Encourage former workers and their household contacts to inform their regular physician about their exposure to asbestos. If former workers or their household contacts are concerned or symptomatic, they should be encouraged to see a physician who specializes in asbestos-related lung diseases.

Public health action plan

- ATSDR will develop and disseminate reliable and easily accessible information concerning asbestos-related health issues for exposed individuals and health care providers.

- ATSDR will publicize the findings of this health consultation in the community around the site. ATSDR will make the report accessible in the community and on the Internet.

- ATSDR will notify former workers for whom we have contact information and provide exposure and health information about asbestos.

- ATSDR is researching and determining the feasibility of conducting additional worker and household contact follow-up activities.

Current or future workers and their household contacts

Areas of residual Libby asbestos contamination may remain in the soil in some areas on the site of the former W.R. Grace facility. The site is currently vacant and surrounded by a 6-foot chain link security fence. Because no workers are present on-site, the current occupational exposure pathway is incomplete, and this pathway poses no public health hazard.

If the site is redeveloped in the future, workers and contractors could be exposed to Libby asbestos from contaminated soil on the site, particularly during on-site construction activities. Insufficient data are available to assess the possible exposure, therefore this pathway is considered an indeterminate public health hazard.

Household contacts of future workers at the site could be exposed to asbestos fibers if the workers do not shower or change clothes before leaving work. It is likely that this exposure would be of very low concentration and short duration and would not significantly increase the risk of health effects. This pathway therefore represents no apparent public health hazard to household contacts of future on-site workers.

Recommendation

- Ensure that adequate controls are in place to protect on-site workers and nearby residents from asbestos exposure during excavation or disturbance of on-site soils.

Public health action plan

- ATSDR will notify the site owner, state and local health departments, and the local planning/permit department as appropriate to inform them of the findings and recommendations regarding the site.

Community members who lived near the facility (1953 to 1992)

The people in the community around the site during the time the Dallas facility processed Libby vermiculite could have been exposed to Libby asbestos fibers in a number of ways: from disturbing or playing in contaminated soil or waste piles on the site; from plant emissions; from waste rock brought home for personal use; or from indoor household dust that contained Libby asbestos from one or more outside sources. Insufficient information is available to determine whether these exposures occurred and, if so, how often they may have occurred, or what concentrations of airborne Libby asbestos may have been present during potential exposures. This information may never be available. Because critical information is lacking, these past exposure pathways for community members are considered indeterminate public health hazards.

Recommendations

- Promote awareness of potential past asbestos exposure among community members who lived near the facility from1953 to 1992. Provide these people with easily accessible materials that will assist them in identifying their own potential for exposure.

- Encourage persons who lived in the community in the past and feel they were exposed to inform their regular physician about their potential asbestos exposure.

Public health action plan

- ATSDR will develop reliable, easily accessible, and understandable information concerning asbestos-related health issues for individuals who may have been exposed and for health care providers in the area.

- ATSDR will publicize the findings of this health consultation in the community around the site. ATSDR will make the report accessible in the community and on the Internet.

Community members who live near the site now (1992 to present)

The Dallas facility no longer processes vermiculite at the site; they stopped processing vermiculite from Libby in 1992. Many of the community exposure pathways, such as ambient emissions and disturbing or playing on on-site waste piles, have been eliminated. Areas of residual Libby asbestos contamination may remain in the soil on the site of the former W.R. Grace facility; however, the site is not accessible to the public. These exposure pathways pose no public health hazard to the surrounding community members.

Currently, individuals in the community could be exposed to airborne Libby asbestos from waste rock used as fill material, for gardening, for driveway paving, or for other purposes. This exposure pathway is an indeterminate public health hazard because insufficient information is available to determine whether waste rock was taken off the site and used in the community.

Recommendations

- Promote awareness of potential asbestos exposure from direct contact with waste rock brought home from the facility in the past. Provide easily accessible materials to help community members in identifying their own potential for exposure.

Public health action plan

- ATSDR will develop reliable, easily accessible, and understandable information concerning asbestos-related health issues for individuals who may have been exposed and for health care providers in the area.

- ATSDR will publicize the findings of this health consultation in the community around the site. ATSDR will make the report accessible in the community and on the Internet.

Author, Technical Advisors

Author

Barbara Anderson, M.S., P.E.

Environmental Health Scientist

Division of Health Assessment and Consultation, ATSDR

Regional Representative

Patrick Young

Regional Representative, Region 6

Division of Regional Operations, ATSDR

Technical Reviewers

John Wheeler, Ph.D., DABT

Senior Toxicologist

Division of Health Assessment and Consultation, ATSDR

Susan Moore, M.S.

Branch Chief, Exposure Assessment and Consultations Branch

Division of Health Assessment and Consultation, ATSDR

References

1. W.R. Grace & Company. Letter to JJ Martin (On-Scene Coordinator, EPA Region 6) from RR Marriam (Remedium Group (a subsidiary of W.R. Grace)) concerning details of the ownership of the property located at 2651 Manila Road, Dallas, Texas. Memphis: W.R. Grace & Company. February 9, 2001.

2. Philip Environmental Services. Summary report: W.R.Grace, 2651 Manila Road, Dallas, Texas, cleaning of vermiculite plant. Prepared for W.R. Grace & Company. February 1997.

3. Dallas Central Appraisal District. Property tax records. State of Texas [Internet resource]. Available at: www.dallascad.org. Accessed 11/16, 2004.

4. Aerial Photography Print Service for 2651 Manila Road, Dallas, Texas 75212. Historical aerial photographs from Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (1942, 1958), Texas Department of Transportation (1970, 1984, 1996), Texas Natural Resource Information System (2001). Milford, Connecticut: Environmental Data Resources, Inc.; 2004.

5. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. Trip report: Region 6, September 2002. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; November 2002.

6. Bureau of the Census. Census 2000. U.S. Department of Commerce. Available at: http://www.census.gov.

7. National Weather Service: Southern Region Headquarters (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Dallas/Fort Worth climatology. US Department of Commerce. Available at: http://www.srh.noaa.gov/fwd/CLIMO/dfw/dfwclimo.html. Accessed September 17, 2004.

8. US Geological Survey. Reconnaissance study of the geology of U.S. vermiculite deposits - are asbestos minerals common constituents? Denver: US Department of the Interior; May 7 2002.

9. Atkinson GR, Rose D, Thomas K, Jones D, Chatfield EJ, Going JE. Collection, analysis, and characterization of vermiculite samples for fiber content and asbestos contamination. Prepared for EPA Office of Pesticides and Toxic Substances, Field Studies Branch, by Midwest Research Institute. Washington: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; September 1982.

10. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Introduction to 29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, 1926, occupational exposure to asbestos. Federal Register 1994 August 10;59:40964-41162.

11. Remedium Group (subsidiary of W.R. Grace). Letter to Barbara Anderson (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) from Robert R. Marriam transmitting company documents concerning air sampling/monitoring and waste disposal practices for selected expansion facilities. March 10, 2003.

12. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. Western Mineral Products health consultation, Minneapolis, Hennepin County, Minnesota. Prepared for ATSDR by Minnesota Department of Health. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; May 2001.

13. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. W.R. Grace Dearborn Plant health consultation, Dearborn, Wayne County, Michigan. Prepared for ATSDR by Michigan Department of Community Health. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; October 2004.

14. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. Toxicological profile for asbestos (update). Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; September 2001.

15. Amandus HE, Althouse R, Morgan WK, Sargent EN, Jones R. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: Part III. Radiographic findings. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11(1):27-37.

16. Amandus HE, Wheeler R. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: Part II. Mortality. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11(1):15-26.

17. Amandus HE, Wheeler R, Jankovic J, Tucker J. The morbidity and mortality of vermiculite miners and millers exposed to tremolite-actinolite: Part I. Exposure estimates.[see comment]. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11(1):1-14.

18. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. Health consultation: mortality in Libby, Montana (1979-1998). Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; August 2002.

19. McDonald JC, McDonald AD, Armstrong B, Sebastien P. Cohort study of mortality of vermiculite miners exposed to tremolite. British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1986;43(7):436-44.

20. Peipins LA, Lewin M, Campolucci S, Lybarger JA, Miller A, Middleton D, et al. Radiographic abnormalities and exposure to asbestos-contaminated vermiculite in the community of Libby, Montana, USA. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(14):1753-9.

21. Lockey JE, Brooks SM, Jarabek AM, Khoury PR, McKay RT, Carson A, et al. Pulmonary changes after exposure to vermiculite contaminated with fibrous tremolite. Am Rev of Respir Disease. 1984;129(6):952-8.

22. Wright RS, Abraham JL, Harber P, Burnett BR, Morris P, West P. Fatal asbestosis 50 years after brief high intensity exposure in a vermiculite expansion plant. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(8):1145-9.

23. Berman DW, Crump KS. Technical support document for a protocol to assess asbestos-related risk (final draft). Prepared for EPA Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response. Washington October 2003.

24. US Environmental Protection Agency. Report on the peer consultation workshop to discuss a proposed protocol to assess asbestos-related risk. Prepared for EPA by Eastern Research Group, Inc. Washington: EPA Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response; May 30 2003.

25. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. Report on the expert panel on health effects of asbestos and synthetic vitreous fibers: the influence of fiber length. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003.

26. McDonald JC, McDonald AD. Chrysotile, tremolite and carcinogenicity. Ann Occup Hyg. 1997;41(6):699-705.

27. US Environmental Protection Agency. Removal assessment results for Texas Vermiculite, Dallas, Dallas County, Texas. Prepared for EPA Region 6 by Roy F. Weston. Dallas: EPA; May 2001.

28. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. World Trade Center response activities close-out report: September 11, 2001 April 30, 2003. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; May 16 2003.

29. US Environmental Protection Agency. World Trade Center indoor environmental assessment: selecting contaminants of potential concern and setting health-based benchmarks. New York City: EPA Region 2; May 2003.

30. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Asbestos-containing materials in schools, final rule and notice. Federal Register 1987 October 30;52:41826-41845.

31. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: National emission standards for hazardous air pollutants; asbestos NESHAP revision. Federal Register 1990 November 20;55:48415.

32. US Environmental Protection Agency. Memorandum to Superfund National Policy Managers, Regions 1-10 from Michael B. Cook (Director, Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation, EPA) clarifying clean-up goals and identification of new assessment tools for evaluating asbestos at Superfund cleanups. Washington: EPA. August 10, 2004.

33. US Environmental Protection Agency. Memorandum to Paul Peronard (On-Scene Coordinator, Libby Asbestos Site, EPA Region 8) from Christopher P. Weiss (Senior Toxicologist/Science Support Coordinator, Libby Asbestos Site, EPA Region 8) Amphibole mineral fibers in source materials in residential and commercial areas of Libby pose an imminent and substantial endangerment to public health. Denver: EPA. December 20, 2001.

34. US Environmental Protection Agency. Memorandum to Joyce Ackerman (On-Scene Coordinator, EPA Region 8) from Aubrey K. Miller (Senior Medical Officer and Regional Toxicologist, EPA Region 8) Endangerment Memo: health risks secondary to exposure to asbestos at former Intermountain Insulation facility at 800 South 733 West, Salt Lake City. Denver: EPA. March 24, 2004.

35. US Environmental Protection Agency. Priority review level 1 - asbestos-contaminated vermiculite. Washington: EPA; June 1980.

36. PLM Company. Phase I environmental site assessment, Dallas Vermiculite Plant, 2651 Manila Road, Dallas, Texas. Prepared for W.R. Grace & Company by PLM Company. July 1994.

37. Anderson HA, Lilis R, Daum SM, Selikoff IJ. Asbestosis among household contacts of asbestos factory workers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:387-99.

38. Powell C, Cohrssen B. Asbestos. In: Bingham E, Cohrssen B, Powell C, eds. Patty's Toxicology 5th Edition: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2001.

39. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Control. Vermiculite Northwest health consultation, Spokane, Spokane County, Washington. Prepared for ATSDR by Washington State Department of Health. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; July 2004.

40. US Environmental Protection Agency. Removal assessment report for Libby vermiculite ore in R6. Prepared for EPA Region 6 by Ecology and Environment, Inc. Dallas: EPA; November 22 2000.

Figures

Figure 1. Site location and 1990 demographic statistics, former W.R. Grace/Texas Vermiculite

Figure 2. Area map showing property boundaries*

*Available at www.dallascad.org; accessed on November 16, 2004.

Figure 3. Aerial photograph of the site, 1995*

*Source: Aerial Photography Print Service for 2651 Manila Road, Dallas, Texas 75212. Historical aerial photograph from US Geological Survey (1995). Milford, Connecticut: Environmental Data Resources, Inc.; 2004.

Figure 4: Meteorological data from the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport*

Figure 5. Vermiculite

Figure 6. Waste Rock

Figure 7. Airborne PCM fiber concentrations over time: personal sample data (N=286*) at the Texas Vermiculite/W.R. Grace Dallas facility, Dallas, Texask

Figure 8. Airborne PCM fiber concentrations over time: area sample data (N=115*) at the Texas Vermiculite/W.R. Grace Dallas Plant, Dallas, Texas

This page last updated on October 30, 2008