You are here: Home › Feature Stories › From Research to Field Applications…Like Bridging Death Valley?

From Research to Field Applications…Like Bridging Death Valley?

Do a computer search on the term "scientific method," and any nonscientist is likely to leave at least somewhat enlightened.

You’ll pick up, for instance, that the scientific method is not a single narrowly–defined and rigid formula. Rather, it’s a set of techniques for examining and, where justified, refining existing understandings, and for incorporating newly acquired knowledge.

You’ll learn that scientists routinely propose hypotheses to help explain a phenomenon or set of phenomena, and that they then test those hypotheses to see how they stand up. Through repetition by others and measurable evidence, those hypotheses may sink or swim, leading to development of new or revised hypotheses and ultimately to increasingly reliable predictions of results.

At its best, the scientific method is continuous, on and on without end and forever in search of new understandings and new knowledge. Accepted scientific "truths" understandably attract less of the professional scientists’ curiosity, and finite research resources, than areas still on the proverbial cutting edge of science.

The non–scientist exploring the scientific method will learn too that the process depends on its being conducted objectively to avoid any bias in the results or in interpreting them. It requires thorough documentation of the methodology and data and relies upon transparency so that other scientists can reproduce and verify or contest earlier results.

Going Beyond a Text Book DefinitionSome things the non–scientist will not learn from an online or text book introduction to the scientific method:

- What happens to the actual products and services—the knowledge—that is one byproduct of the scientific research?

- How are those products and services best put to effective use in actual practice?

- Will end–users have what it takes—resources, funds, know–how, etc.—when the time comes for them to put those products and services to work?

- And, importantly, how might scientists from their laboratories and field work, factor into their thinking those kinds of considerations?

Doing Science that ‘makes a difference’

No question that you’ll find the fruits of NCCOS research in the libraries and research laboratories of scientists dealing with coastal and ocean resources. But finding them also "on the street," so to speak—in daily practical applications aimed at better managing those same resources—is also critical.

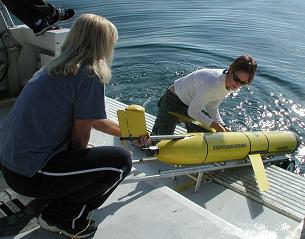

NCCOS scientists determined to see their scientific exploits "make a difference" in the real world know the situation well. What good, for instance, does it do to develop a new testing protocol or detection kit for managing the risks posed by a harmful algal bloom if that tool never finds its way out of the laboratory and into the field? Why work for years to develop the ecological forecasting capabilities needed to better anticipate rainfall flushes of coliform bacteria from land to water, or to forecast a needed shellfish closure, if the tool doesn’t find its way into practical use in the field, and not solely to academic analyses in laboratories?

NCCOS scientists determined to see their scientific exploits "make a difference" in the real world know the situation well. What good, for instance, does it do to develop a new testing protocol or detection kit for managing the risks posed by a harmful algal bloom if that tool never finds its way out of the laboratory and into the field? Why work for years to develop the ecological forecasting capabilities needed to better anticipate rainfall flushes of coliform bacteria from land to water, or to forecast a needed shellfish closure, if the tool doesn’t find its way into practical use in the field, and not solely to academic analyses in laboratories?

Saying it is one thing. Doing it, and doing it well and consistently, can be an entirely different matter, as NCCOS managers know all too well.

It isn’t always easy, let’s acknowledge, to get scientists used to conducting their work in one way—that is, with an emphasis on the science of their work—to think also about the kinds of issues generally more in the domain of marketers and MBAs.

To tackle that particular issue, says NCCOS Director Gary C. Matlock, Ph.D., "it’s important for our scientists to involve our customers, our end–users, early in the process. It’s critical that our constituents and customers have a real expectation of what it is we are trying to address to meet their needs.

"We need to engage them early and in a very serious way right from the start," Matlock emphasizes. "We need to set up that two–way faucet of communication and involvement early, and we need to then be able to hold them accountable for using the developed products to meet their needs, just as they should hold us accountable for our own scientific research."

The Out-Year Budgeting ChallengeThere are other challenges too in the effort to move NCCOS and other federal agency scientific research activities to the operational stage. One challenge involves the very nature of the federal budgeting process, Matlock points out.

He points to the inevitable obstacles in setting aside federal funds, let’s say, five years ahead in the face of restrictive disincentives for going beyond year-to-year budgeting. That’s an area in which government scientists hope to see a growing role for innovative partnerships over coming years, partnerships both among federal agencies and involving collaboration with the private sector.

He points to the inevitable obstacles in setting aside federal funds, let’s say, five years ahead in the face of restrictive disincentives for going beyond year-to-year budgeting. That’s an area in which government scientists hope to see a growing role for innovative partnerships over coming years, partnerships both among federal agencies and involving collaboration with the private sector.

The strongest NCCOS advocates for refining and streamlining the research-to-operational nexus have a term they use in confronting the situation: "bridging the valley of death."

The term illustrates the extent of the challenges they are dealing with in forcing these transitions.

But it underscores also the level of commitment that NCCOS science managers and scientists bring to the effort to see that their work finds a home where it is most needed—in the hands of coastal resource managers eager to find effective ways to manage coastal resources and minimize unnecessary risks.

Other recent articles