|

|

FoodNet News - Fall 2008: Volume 2, Issue 4 |

|

|

| FoodNet Home

> FoodNet

News > Fall 2008 – Volume 2, Issue 4

|

|

|

FoodNet News - Fall 2008: Volume 2, Issue 4  PDF 341KB PDF 341KB

The Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) is the principal foodborne disease component of CDC’s Emerging Infections Program. FoodNet is a collaborative project of the CDC, ten sites (CA, CO, CT, GA, MD, MN, NM, NY, OR, TN), the U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The CDC FoodNet Team is in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch (EDEB), in the Division of Foodborne, Bacterial, & Mycotic Diseases (DFBMD) in the National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, & Enteric Diseases (NCZVED).

Inside This Issue

- Burden and Trends in Listeria monocytogenes

- Spotlight: Listeria in the Literature

- Noroviruses: Burden and Recent Trends

- Persistent Gastroenteritis Outbreak Due to New Variant Norovirus

- Yersinia in FoodNet, 1996-2007

- Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in FoodNet, 1996-2007

- Decline in Yersinia enterocolitica Infections in FoodNet, 1998-2006

- Summary of Burden of Illness Meeting

- Recently Presented Abstracts at IAFP and Recently Published Manuscripts

- Special Hand Washing Handout

Listeriosis is an infection caused by consuming food contaminated with the bacteria Listeria monocytogenes. It is estimated that there are 2,500 cases in the United States each year, 500 of which result in death1. Symptoms include fever, muscle aches, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and diarrhea, sepsis, and meningitis. Although anyone can develop listeriosis, it primarily affects the elderly, pregnant women, newborns, and persons with weakened immune systems, cancer, diabetes, kidney disease, or AIDS. Listeriosis can results in serious complications, including miscarriages and still births. Persons at high risk for listeriosis can become ill after consuming only a few bacteria. Illness begins 3-70 days after exposure (median 3 weeks) and large outbreaks have occurred. Listeria is commonly found in soil and water and can be present in animals with no signs of illness. Raw meats and unpasteurized dairy products can contain Listeria, and vegetables can be contaminated directly from soil or from manure used as fertilizer. Listeria is killed by pasteurization and cooking, however, ready-to-eat products such as soft cheeses and deli meats are sometimes contaminated after processing making them an important source of illness.

FoodNet monitors trends in listeriosis over time. From baseline (1996-1998), Listeria infections have decreased by 42% with rates reaching 0.27 per 100,000 in 20072 nearly meeting the 2010 Healthy People objective of 0.24 per 100,000. To identify potential outbreaks, Listeria isolates are routinely subtyped using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) at state health departments and patterns submitted to CDC PulseNet for comparison to national data. In addition to widely recognized risks such as hot dogs, deli meats, soft cheeses and unpasteurized milk, a recent study of sporadic disease conducted in FoodNet sites identified consumption of hummus and melons as new risk factors for illness (see article below).

To prevent listeriosis, persons should thoroughly cook raw food from animal sources, wash vegetables before eating, keep uncooked meats separate from cooked and read-to-eat products, do not consume unpasteurized milk or foods made from unpasteurized milk, and consume perishable foods as soon as possible. In addition, persons at high risk should avoid consuming hot dogs and deli meats unless they are reheated until steaming; feta, Brie, Camembert, blue-veined or Mexican-style cheeses unless they are made from pasteurized milk; refrigerated pates or meat spreads; and refrigerated smoked seafood unless it is cooked.

For more information on listeriosis, visit: http://www.cdc.gov/nczved/dfbmd/disease_listing/listeriosis_gi.html.

—Mary Patrick, CDC, FoodNet

- Mead et al. Food-Related Illness and Death in the United States. EID Vol 5, Sep 1999.

- Preliminary FoodNet Data on the Incidence of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food --- 10 States, 2006. MMWR. April 13, 2007 / 56(14);336-339.

Return to top

Listeria infections were the focus of two articles in the January 2007 edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases. One describes continued reductions in listeriosis in the U.S. FoodNet sites, and the other describes a case-control study in the FoodNet sites to determine possible sources of sporadic infection.

The Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, or FoodNet, is a collaborative sentinel site surveillance program for foodborne infections conducted as part of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program. FoodNet conducts active surveillance for laboratory-confirmed foodborne disease, including listeriosis, in 10 U.S. states. In addition, FoodNet conducts periodic telephone surveys of high-risk food consumption among a sample of several thousand people living in the FoodNet sites.

From 1996 though 2003, there were 766 cases of listeriosis identified and 21% of these cases were fatal. The rate of listeriosis dropped significantly by an estimated 24%, from 4.1 cases per million people in 1996 to 3.1 cases per million people in 2003. Pregnant Hispanic women and people more than 50 years old were disproportionately affected. Based on the FoodNet Population survey, persons of Hispanic ethnicity were more likely to report eating cheese made from unpasteurized milk, a known high risk food for listeriosis. The data from this analysis suggest that the efforts of federal regulatory agencies (Food and Drug Administration and the US Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service) continue to be effective in reducing the burden of listeriosis in the United States.

Outbreaks associated with Listeria monocytogenes have been widely studied, and interventions to reduce illness have been targeted at foods implicated in these outbreaks. However, few studies have focused on determining potential sources for sporadic L. monocytogenes infection. In 2000, FoodNet conducted a case-control study to examine the effect of industry and government regulations in targeting known sources of L. monocytogenes and to determine additional sources that could be targeted by interventions. The study was conducted in nine states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, and Tennessee, and the questionnaire included questions about medical history, consumption of various foods and beverages, animal contact, and travel in the four weeks prior to specimen collection for case patients.

Eating hummus prepared in a commercial establishment and eating melons at a commercial establishment were found to be associated with Listeria infection. These findings suggest that retail environments may play an important role in the contamination of foods with L. monocytogenes and interventions targeted at retail venues may help reduce sporadic infection. Furthermore, pregnant women, the immunocompromised, and other persons at increased risk may wish to avoid consumption of the new foods associated with infection1.

—Nadine Oosmanally, CDC, FoodNet

- Summary of Voetsch et al. Reduction in the Incidence of Invasive Listeriosis in the FoodNet sites, 1996-2003. Clin Infect Dis; 2007 Vol 44: 513-520 and Varma et al. Listeria monocytogenes Infection from Foods Prepared in a Commercial Establishment: A Case-Control Study of Potential Sources of Sporadic Illness in the United States. Clin Infect Dis; 2007 Vol 44: 1-8.

Return to top

Noroviruses (NoVs) are now recognized as the most frequent cause of infectious gastroenteritis and foodborne illness worldwide. Each year in the United States, there occur an estimated 23 million cases of NoV, of which approximately 40% are due to foodborne transmission1. The illness begins after an incubation period of 12–48 hours and is typically characterized by acute-onset vomiting and/or diarrhea, which can be very debilitating and lead to dehydration. Most healthy individuals will recover with no sequelae after 1–3 days, but evidence now suggests that maybe 10% of patients with NoV diarrhea seek medical attention and some may require hospitalization and fluid therapy2.

In addition, illness in the elderly may be more severe and perhaps result in

death, as indicated during recent outbreaks in long-term care facilities3.

Noroviruses are transmitted by a variety of routes, including directly from person to person, via contaminated food or water, contamination of the environment and through aerosolization of vomitus. In the United States, NoVs are responsible for up to 50% of all foodborne

gastroenteritis outbreaks and often involve ready-to-eat food items such as

salads, sandwiches, or fresh produce2,4. In most outbreaks, these items are assumed to be contaminated at point of service by a NoV-infected food worker, even in the absence of infection in these workers. However, several outbreaks, particularly those in which raspberries have been implicated, have shown that contamination of fresh produce can also occur at the point of source5. A recent investigation found that read-to-eat meats could be contaminated with norovirus before vacuum packaging6.

These numerous transmission modes can make investigations of source and

transmission of virus in an outbreak difficult, but all possibilities of

transmission should be considered. Recently, new variant strains of NoV have

emerged every 3-4 years and have caused sharp increases in winter occurrence

of person-to-person outbreaks in nursing homes, but apparently not foodborne

outbreaks7.

Control and prevention of norovirus outbreaks is also challenging, due to the low infectious dose of the virus (10-100 particles), prolonged shedding (up to 2–3 weeks after recovery), environmental stability, and resistance to common disinfectants, freezing, drying, and low pH. Efforts to reduce norovirus infections should focus on education, hand hygiene, implementation of effective policies to exclude persons recovered from diarrheal illness for at least 24 hours after recovery (FDA food code)8, and appropriate disinfection using EPA- or CDC-recommended agents9.

While the absence of a routine culture system for human NoVs has hampered

identification of effective disinfectants, the recent discovery of a

cultivable murine NoV has opened the possibility of a more appropriate

surrogate for norovirus that the more distantly related respiratory virus,

feline calicivirus10,11.

Advances in molecular techniques have greatly expanded our understanding of NoV

epidemiology and diversity12. All 50 state public health laboratories in the United States now have the capability to perform reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay (RT-PCR) and many can perform real-time RT-PCR and genetic sequencing. Further efforts to develop simple, inexpensive, and accurate antigen detection assays are still needed to move NoV diagnostics into clinical settings and better characterize the disease burden.

Two new surveillance systems are being developed that will improve our understanding of burden, transmission of noroviruses, and variations in strain virulence. In collaboration with state partners, CDC will soon implement the National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS) which will routinely collect data on both foodborne and person-to-person NoV outbreaks. In addition, the National Norovirus Outbreak Surveillance Network (CaliciNet) is currently undergoing beta-testing and will soon allow state health department laboratories to share outbreak data with CDC and other states by directly uploading NoV sequences and relevant epidemiologic information.

The widespread use of improved diagnostics and implementation of these surveillance systems will promote better detection and control of NoV.

—Aron Hall and Marc-Alain Widdowson, CDC, Division of Viral Diseases

- Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, et al. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. Sep-Oct 1999;5(5):607-625.

- Widdowson MA, Sulka A, Bulens SN, et al. Norovirus and foodborne disease, United States, 1991-2000. Emerg Infect Dis. Jan 2005;11(1):95-102.

- Norovirus activity--United States, 2006-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Aug 24 2007;56(33):842-846.

- Turcios RM, Widdowson MA, Sulka AC, Mead PS, Glass RI. Reevaluation of epidemiological criteria for identifying outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis due to norovirus: United States, 1998-2000. Clin Infect Dis. Apr 1 2006;42(7):964-969.

- Gaulin CD, Ramsay D, Cardinal P, D'Halevyn MA. [Epidemic of gastroenteritis of viral origin associated with eating imported raspberries]. Can J Public Health. Jan-Feb 1999;90(1):37-40.

- Barzilay EJ, Malek MA, Kramer A, et al. An outbreak of gastroenteritis among rafters on the Colorado River caused by norovirus contamination of commercially packaged deli meat. Paper presented at: 5th International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases; March 19-22, 2006, 2006; Atlanta, GA.

- Blanton LH, Adams SM, Beard RS, et al. Molecular and epidemiologic trends of caliciviruses associated with outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis in the United States, 2000-2004. J Infect Dis. Feb 1 2006;193 (3):413-421.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Code. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/fc05-toc.html. Accessed August 21, 2008.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. List G. EPA's Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Norovirus. http://www.epa.gov/oppad001/list_g_norovirus.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2008.

- Wobus CE, Karst SM, Thackray LB, et al. Replication of Norovirus in cell culture reveals a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS Biol. Dec 2004;2(12):e432.

- Cannon JL, Papafragkou E, Park GW, Osborne J, Jaykus LA, Vinje J. Surrogates for the study of norovirus stability and inactivation in the environment: aA comparison of murine norovirus and feline calicivirus. J Food Prot. Nov 2006;69(11):2761-2765.

- Zheng DP, Ando T, Fankhauser RL, Beard RS, Glass RI, Monroe SS. Norovirus classification and proposed strain nomenclature. Virology. Mar 15 2006;346(2):312-323.

Return to top

There are an estimated 23 million cases of norovirus infection annually in the United States. Symptoms of norovirus infection include acute onset vomiting, non-bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and nausea. Norviruses are highly contagious and have a low infectious dose. There was a global emergence of two new variant GII.4 strains associated with an increased number of outbreaks during 2006 and 2007.

On October 19th, 2006 CDC was contacted by a private citizen who reported “flu-like” illness while aboard a riverboat traveling with a group from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati from October 14th to 18th. The traveler reported that other members of his group also became ill, as well as other passengers and crew members on the cruise.

On October 20th, the riverboat company that operated the cruise was contacted; the company noted there were approximately 30 ill passengers on the current cruise underway from Cincinnati to St. Louis. Since these illnesses accounted for over 5% of the cruise population, the riverboat company had contacted the regional FDA office. On October 21st a CDC team departed for Kentucky to meet the riverboat at the next port.

For this investigation we defined a case as vomiting or diarrhea in a passenger or crew member aboard Cruise Ship A from September 1st to October 29th, 2006, with illness onset while on board, or within 7 days of disembarking. Case finding was conducted by reviewing the GI illness logs maintained by the ship’s hotel manager and administering a questionnaire distributed to passengers and crew members.

We conducted a cohort study among passengers aboard Cruise Ship A during Cruise II (October 18 – 25) to assess food and environmental exposures to determine risk factors for illness. The results of case-finding showed that 227 or 43% of those aboard the riverboat met the case definition. Among the cases 85% reported diarrhea, 75% reported vomiting, 66% reported diarrhea and vomiting, and 12% were hospitalized.

A total of 171 Cruise II passengers participated in the cohort study, 79 met the case definition. There was an increased risk of illness among passengers who shared a dining table or cabin with an ill person, or who witnessed a person vomiting.

Cruise II was terminated early in Cape Girardeau, MO. The riverboat company began a one day sanitation of Cruise Ship A which included:

- Re-cleaning of all hard surfaces with 1000 part per million chlorine bleach solution and all porous surfaces with a phenolic disinfectant

- Replacing or professionally laundering all linens

- Replacing all air filters

CDC and FDA provided a presentation to incoming passengers before they boarded the boat about norovirus, handwashing, and the importance of isolation during illness. Passengers were given the option of a refund for the cruise if they did not want to embark following the presentation. The one day sanitation had been completed and Cruise III, an eight day cruise from St. Louis, MO to St. Paul, MN departed as scheduled on October 25th.

There were no illnesses reported to the ship’s GI log on October 26th, but FDA inspectors on board notified the CDC team that 6-9 passengers had reported illness when the boat docked in Hannibal, MO on the morning of October 27th. Case finding was conducted and found 74 people or 14% of those aboard the riverboat during Cruise III were ill with vomiting and/or diarrhea. It was recommended that Cruise III be terminated immediately in Hannibal, MO, that the riverboat be re-sanitized, and that no passengers should be on board for at least 6 days. Following early termination, the riverboat underwent a 10 day sanitation after which no further illnesses were reported.

Stool samples were collected from a total of 24 cases from each of the three consecutive cruises. These were negative for bacterial enteric pathogens, but 18 were positive for Norovirus Genogroup II. Strains from passengers on three different cruises were sequenced and shared the identical sequence of a new variant GII.4 norovirus strain called Minerva that emerged nationwide in 2006.

This was a persistent outbreak of norovirus on a riverboat, with many primary and secondary cases, spanning consecutive cruises despite cleaning and sanitizing efforts and the attempt to isolate ill passengers. The source of initial infection for this outbreak is unknown but transmission was likely person-to-person as well as via environmental contamination. This investigation highlights the need for domestic cruises to have isolation and control plans as well as clear reporting guidelines in the event of future outbreaks.

—Gwen Ewald, CDC, OutbreakNet

Figure 1. Map of the area that Cruise Ship A traveled during the outbreak with embarkation and termination points for the three affected cruises, U.S., September – October, 2006. Cruise I was from Pittsburgh, PA to Cincinnati, OH from October 14 – 18. Cruise II was from Cincinnati, OH to St. Louis, MO from October 18 – 25 (terminated early in Cape Girardeau, MO). Cruise III was from St. Louis, MO to St.Paul, MN from October 25 – November 1 (terminated early in Hannibal, MO).

Return to top

Yersiniosis is caused by infection with bacteria in the genus Yersinia. Yersinia belongs to a large family of gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria known as Enterobacteriaceae. There are 11 species of Yersinia, three of which are known to cause human illness: Y. enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. pestis, the causative agent of plague. Yersinia are found worldwide with animals being the main reservoir. The major animal reservoir for Y. enterocolitica strains that cause human illness is pigs, but strains are also found in many other animals including rodents, rabbits, sheep, cattle, horses, dogs, and cats.

FoodNet conducts active surveillance for all enteric Yersinia infections. From 1996 through 2007, FoodNet ascertained information on 1,903 Yersinia infections, an average annual incidence of .55 cases/100,000 persons. Of those with known species information (77%), 92% were Y. enterocolitica (1,355), 4% were Y. frederiksenii (53), 2% were Y. intermedia (23), 1% were Y. pseudotuberculosis (18) and less than 1% were each of the following species: Y. kristensenii (10), Y. aldovae (5), Y. ruckeri (5), Y. bercovieri (1). The median age of patients with a Yersinia infection was eight years (range, <1-99 years); 50% were female; 37% were white; 29% were hospitalized and 18 deaths were reported (<1% case fatality rate). Most cases were diagnosed in the winter months (December to February) and the highest percentage of cases was reported from Georgia (29%).

Transmission of Yersinia is most common via the fecal-oral route by eating or drinking contaminated water, food, or by contact with infected persons or animals. Common symptoms of yersiniosis include fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and less frequently, nausea and vomiting. Symptoms are not readily differentiated from other enteric pathogens and persist 1-3 weeks (may last several months). In a small proportion of cases, complications such as pseudotuberculosis, erythema nodosum, reactive arthritis, or septicemia can occur. Diagnosis is usually made by stool culture.

Treatment for yersiniosis includes fluid and electrolyte replacement. In most instances infections are self-limiting. Antibiotic treatment may reduce the duration of fecal shedding, but benefits for uncomplicated cases are not well established. Patients with septicemia or underlying medical conditions should receive antibiotic therapy.

To reduce exposure to Yersinia, wash your hands before preparing and eating meals and after contact with animals. Avoid consumption of raw or undercooked pork products, unpasteurized milk, or untreated water. Persons handling pork intestines or other raw pork products should thoroughly wash their hands before caring for infants.

Yersinia is likely underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and underreported. Yersiniosis is not a nationally notifiable disease and isolation of bacteria from stool is difficult. To better understand the epidemiology of Yersinia species we need national surveillance, more advanced laboratory detection methods, and further epidemiologic and intervention studies.

—Cherie Long, CDC, FoodNet

Return to top

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is rare in the United States. Of the 1,903 Yersinia infections reported in FoodNet sites from 1996 through 2007, 18 (<1%) cases of Y. pseudotuberculosis infection were identified, for an average annual incidence of Y. pseudotuberculosis of 0.04 cases per 1,000,000 persons. The median age of patients was 47 years (range, 16-86); 67% were male; and 56% were white. Most cases were reported from the western FoodNet sites; 5 cases each from California and Oregon, two cases each from Connecticut, Georgia, and Minnesota, and one case each from Maryland and New York. Nearly half (8) of the cases were reported during the winter months. Seventy-two percent of patients required hospitalization and 1 death was reported (6% case fatality rate). Twelve of the 18 (67%) patients had Yersinia pseudotuberculosis isolated from an invasive specimen collection site, compared with only 8% of patients with Y. enterocolitica infection.

FoodNet data provides the best glimpse we have into the differences among Yersinia species in the United States. Because of the lack of routine screening for Yersinia and the use of suboptimal culture media for isolation of Y. pseudotuberculosis, it is likely that many Y. pseudotuberculosis infections may go undiagnosed. Further investigation is necessary to fully understand why there are so few cases of Y. pseudotuberculosis identified in the United States and to ensure that Y. pseudotuberculosis does not make up a large amount of the gastroenteritis due to unknown etiology.

—Cherie Long, CDC, FoodNet

Return to top

Yersinia enterocolitica causes febrile gastroenteritis and is the most common cause of human yersiniosis in the United States. Y. enterocolitica is a zoonotic infection with pigs serving as the main animal reservoir for human illness. Infection is commonly associated with cross contamination during the preparation of chitterlings. The incidence of infection is highest in infants and non-Hispanic blacks and infections are more common during the winter months.

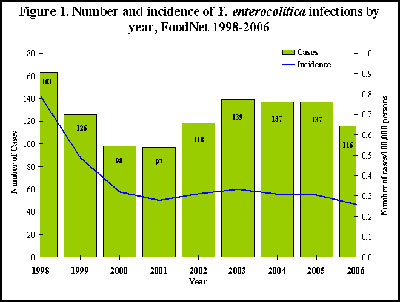

From 1998 to 2006, 1,131 Y. enterocolitica cases were ascertained by FoodNet, an average annual incidence of 0.38 cases/100,000 persons (see Figure 1 below). From 1998 through 2006, the incidence of Y. enterocolitica infections declined by 67%, from 0.79 in 1998 to 0.26 in 2006. Declines were largest in infants (77%, from 18.83 in 1998 to 4.28 in 2006), in non-Hispanic blacks (83%, from 2.41 in 1998 to 0.40 in 2006), and in the state of Georgia (81%, from 1.52 in 1998 to 0.29 in 2006). In Georgia, the incidence in black non-Hispanic infants declined 90%, from 194.12 in 1998 to 19.71 in 2006.

Declines in Yersinia enterocolitica are largely due to the decrease in infections among non-Hispanic blank infants, particularly in Georgia. This decrease is concurrent with educational efforts in Georgia focused on the safe preparation of chitterlings. However, non-Hispanic blacks and infants continue to have the incidence of Y. enterocolitica infection which indicates that continued educational efforts are needed.

—Cherie Long, CDC, FoodNet

Return to top

The 5th Annual Meeting of the International Collaboration on Enteric Disease Burden of Illness Studies was held as a satellite meeting to Food Micro Meeting on August 31st, 2008 in Aberdeen, Scotland.

Shannon Majowicz from the Public Health Agency of Canada gave an update on the status of the International Collaboration, provided an overview of the United Kingdom’s second Infectious Intestinal Disease Study and described an on-going analysis of respiratory symptoms in cases of gastrointestinal illness. Fumiko Kasuga from the National Institute of Public Health in Japan described the burden of illness study being conducted in Japan. In addition, Fred Angulo from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States provided an update on the burden of illness study that is being conducted in the Henan province in China.

Elaine Scallan from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States described the progress that has been made on estimating the global burden of salmonellosis. Katie Fullerton from the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing provided an update on the progress of an international comparison of case-control methodologies. A website for the International Collaboration is under construction and will be available for use this fall. This site will be linked from the CDC FoodNet website.

The Collaboration will form a working group committed to calculating Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and a working group dedicated to estimating the global burden of listeriosis.

The 6th Annual Meeting of the International Collaboration on Enteric Disease Burden of Illness Studies will be held in Tokyo, Japan, August 31st-September 1st.

—Ashton Wright, CDC, Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch

For additional information or to join the International Collaboration please email: apwright@cdc.gov or ICOFDN@listserv@cdc.gov

Return to top

Recently Presented Abstracts at the International Association for Food Protection (IAFP) August 3-6, 2008

- Ayers, T. et al. Epidemiology of Seafood-Associated Outbreaks.

- Ayers, T. et al. Food Commodities Associated with Salmonella Serotypes.

- Grass, J. et al. Evidence for Implicating Food Vehicles in Outbreaks, 1998-2006.

- Gray, S. et al. Enteric Disease Outbreaks Associated with Fairs and Festivals, 1998-2006.

- Jackson, K. et al. Invasive Salmonella Infections in the United States, 1996-2006.

- Mody, R. et al. Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella I 4, [5], 12:i– Infections Associated with Commercially Produced Frozen Pot Pies—United States, 2007.

- Patrick, M. et al. Prevalence of Exposures to Meat and Poultry Products Among Children Riding in Shopping Carts: Increased Risk of Salmonella and Campylobacter Infection.

- Rosenblum, I. et al. A Review of Contributing Factors As Reported to eFORS by FoodNet Sites, 2005-2006.

Recently Published Manuscripts

- Ailes, E. et al. Continued Decline in the Incidence of Campylobacter Infections, FoodNet 1996-2006. Foodborne Pathog Dis; 2008 Vol 5 (3): 329-337.

Return to top

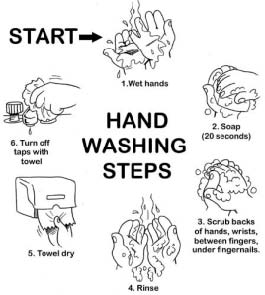

Good Health is in Your Hands! |

- Washing your hands is the simplest and most effective thing you can do to reduce the spread of colds, flu, skin infections and diarrhea.

- Every time you touch your hands to your mouth you can get sick.

- Eating, nail biting, thumb sucking, handling food, and touching toys are all ways germs can spread.

- Even shaking a hand or opening a door can transfer germs to your hands.

|

Always wash your hands... |

Before...

- preparing or eating food

- treating a cut or wound

- tending to someone who is sick

- inserting or removing contact lenses

|

After...

- using the bathroom

- changing a diaper or helping a child use the bathroom (don’t forget the child’s hands!)

- handling raw meats, poultry or eggs

- touching pets, especially reptiles

- sneezing or blowing your nose, or helping a child blow his/her nose

- handling garbage

- tending to someone who is sick or injured

|

Source: Georgia Department of Human Resources | Division of Public Health | http://health.state.ga.us |

Return to top

|

| |

| |

Date:

October 17, 2008

Content source: National Center for Infectious Diseases

|

|

|

|