|

Cancer researchers have worked hard on ways to detect, treat, and prevent cancer during the last 35 years. But ironically, cancer incidence has gone up during this time, from approximately 400 per 100,000 persons in 1975 (according to data collected by NCI's SEER program) to a peak of nearly 510 per 100,000 in 1992; since then, it has effectively stabilized.

However, cancer incidence trends are not always easy to interpret as a measure of success - at least not in the short term. This is because changes in incidence are a function of many factors, including the increased use of screening, the introduction of new diagnostic technologies, and changes in the risk factor profile of the U.S. population, according to Dr. Eric J. (Rocky) Feuer, chief of NCI's Statistical Research and Applications Branch.

"Due to screening and new diagnostic techniques, we're detecting cancer earlier than we used to," Dr. Feuer explains. "The introduction of new screening technologies causes the incidence to go up temporarily, not because there are necessarily more cases, but because we are finding cases earlier than if we waited for symptoms to develop. Although it is somewhat counterintuitive, a rise in incidence associated with screening can be a positive sign, since early detection coupled with effective treatment has the potential to extend life or even cure patients."

"Due to screening and new diagnostic techniques, we're detecting cancer earlier than we used to," Dr. Feuer explains. "The introduction of new screening technologies causes the incidence to go up temporarily, not because there are necessarily more cases, but because we are finding cases earlier than if we waited for symptoms to develop. Although it is somewhat counterintuitive, a rise in incidence associated with screening can be a positive sign, since early detection coupled with effective treatment has the potential to extend life or even cure patients."

"Changes of this type were particularly evident with prostate cancer," he continues, "when incidence went up significantly between 1988 and 1992 because changing biopsy techniques found more cancers and PSA screening was introduced. Incidence rates fell dramatically after screening rates stabilized and have since returned to a more moderate rising trend."

Dr. Feuer also notes that the risk profile of the U.S. population has changed in the past 35 years and is correlated with genuine changes in incidence rates of some types of cancer. "For example, tobacco use rates for white males started dropping in the late 1950s, leading to a flattening of lung and bronchus cancer incidence rates in the 1980s, followed by a decline starting in the late 1980s, 20 to 30 years after cessation trends changed."

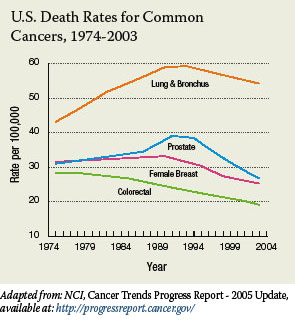

Perhaps a clearer indication of the payoff for our nation's investment in cancer research is the decrease in mortality. U.S. mortality increased from 1975 to 1990, but has been falling since 1994. In addition, mortality rates of the four most common cancers - colorectal, breast, prostate, and lung - which together accounted for more than half of all U.S. cancer deaths in 2003, also showed falling rates.

These cancer mortality trends are linked to earlier screening and better detection methods, but they're also linked to changes in behavior, such as the decrease in smoking, declines in alcohol consumption in the early 1990s, and increases in sun protection in the late 1990s. Dr. Feuer notes, "It takes time to affect mortality rates. Some therapies that began in the 1970s and 1980s [such as adjuvant chemotherapy and hormone therapy for breast cancer] didn't start paying off in reduced mortality until the 1990s."

|