PUBLIC HEALTH PREPAREDNESS: MOBILIZING STATE BY STATE

Section 1: Public Health Preparedness in the States and DC

Response

Improving Communication Systems and Increasing Planning, Training, and Exercising

Public health professionals are on the front lines during an emergency. Establishing emergency response plans was an initial focus of the cooperative agreement. Now, CDC is emphasizing exercises that test systems and validate training to ensure that plans will work during a real event. These activities support CDC preparedness goals in the areas of prevention, detection and reporting, investigation, control, recovery, and improvement.

Quickly communicating up-to-date information. During an emergency, communication from public health professionals must be fast and accurate. In 2007, all states had plans for crisis communication with first responders and healthcare providers during an emergency.21

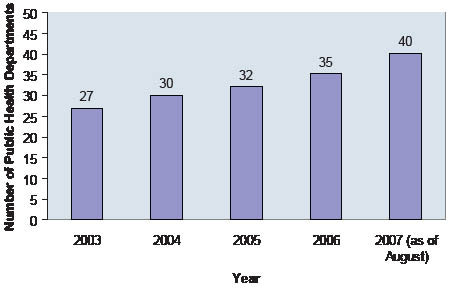

In addition, CDC’s Health Alert Network (HAN) and state-level HANs provide a mechanism for users, including state and local public health departments, hospitals, and physicians, to rapidly exchange critical public health information. The number of states responding to a test HAN message from CDC in 30 minutes or less has increased by 48% since 2003 (Figure 5).22

Figure 5: Public Health Departments Responding to Test HAN Messages in 30 Minutes or Less, 50 States and DC, 2003-2007

Source: CDC, HAN data; 2003-2007 21 CDC, DSLR Mid-Year Progress Report Review data; 2007 22 CDC, HAN data; 2003-2007

Developing emergency response plans. As of 2006, all state public health departments reported having public health emergency response plans. A key element of these plans is detailing roles, responsibilities, and responses to an emergency using the Incident Command System (ICS).23

Distributing the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS). CDC manages the SNS, a national repository of antibiotics, other life-saving medications, and medical supplies, to help public health departments respond to emergencies. The SNS is positioned across the country. In 2001, few states had up-to-date, written plans for receiving, staging, and distributing SNS assets. In contrast, today all states have such plans. Nevertheless, states vary in the sophistication and maturity of the coordination and exercising of those plans.

CDC works closely with state, local, and tribal agencies to help identify and fix SNS planning gaps. CDC reviews the plans annually on a scale from a low of 0 to a high of 100. The reviews include the public health department’s coordination with traditional and nontraditional community partners; receiving, staging, and distributing medical materiel; state legal statutes to aid in the rapid dispensing of medications; and the type and frequency of training, exercising, and evaluation of response plans. In 2006-2007, 73% of the states reviewed satisfactorily documented their planning efforts, which is reflected in a review score of 69 or higher (Table 7).

Planning for pandemic influenza. Since 2006, the cooperative agreement has provided specific funding to public health departments to prepare for pandemic influenza. As part of this effort, every state developed a pandemic influenza response plan. Previously, most states did not have completed plans addressing areas such as enhancing surveillance and laboratory capacity, managing vaccines and antivirals, and implementing community containment measures to reduce influenza transmission.24 In addition, states held summits bringing together partners from state and local public health departments, businesses, schools, hospitals, and other organizations to plan for a potential pandemic.

Training to enhance public health preparedness. An increasing number of staff is now trained to support preparedness and response activities (Figure 6). Subjects covered in the training courses included ICS, risk communication, quarantine and isolation, mental health services during and after emergencies, and working with at-risk populations.25

In addition, following the anthrax attacks of 2001, CDC developed the “Forensic Epidemiology” course as a tool for state and local public health departments and law enforcement agencies to improve joint investigations of terrorism. As of 2004, over 14,000 public health and law enforcement professionals had participated in this course, and staff are continuing to be trained.

Table 7: CDC Reviews of State Strategic National Stockpile Plans, 50 States, 2006- 2007

| Review Score | Number of States |

|---|---|

| 69-100 | 36 |

| 0-68 | 13 |

| Review in progress* | 1 |

|

Source: CDC Division of Strategic National Stockpile (DSNS) data; 2006-2007

*CDC has not completed reviewing all states using a new numerical technical assistance review tool. 23 The Incident Command System (ICS) is the organizational structure for managing incidents that require response from different jurisdictions and disciplines. ICS lays out standard roles and responsibilities for the incident commander and staff. 24 CDC, Pandemic Influenza State Self-Assessments data; 2006 |

|

Exercises Test Public Health Systems and Foster Partnerships

In November 2006, a mass vaccine dispensing exercise was coordinated by the Navajo Area Indian Health Services and the Navajo Division of Health. The exercise provided almost 24,000 seasonal influenza vaccines at 15 different sites around the Navajo Nation (about 25,000 square miles). The exercise simulated a response to a pandemic influenza outbreak. The exercise also tested risk communication and the SNS delivery systems. Several dispensing sites vaccinated as many as 1,000 people per hour during peak times. The Navajo public health system is large and complex, consisting of tribal and federal health agencies as well as agencies from three states and multiple counties. During the exercise, these health agencies worked with the Navajo Police, the National Guard, the National Park Service, and others using ICS. The cooperation demonstrated by these different agencies during the exercise will contribute to future successful emergency responses. Please refer to Section 2 for response examples for each state and directly funded locality.

Figure 6: States Offering Training Courses to State and Local Public Health Professionals, 50 States and DC, 1999-2005

Source: CDC, DSLR data; 1999-2005

25 At-risk or vulnerable population groups may have additional needs before, during, and after an incident in one or more of the following functional areas: maintaining independence, communication, transportation, supervision, and medical care. Individuals in need of additional response assistance may include those who have disabilities; who live in institutionalized settings; who are elderly; who are children; who are from diverse cultures, who have limited English proficiency, or who are non-English speaking; or who are transportation disadvantaged.

Exercises test plans, validate training, and build relationships so people know their roles and responsibilities during an emergency.

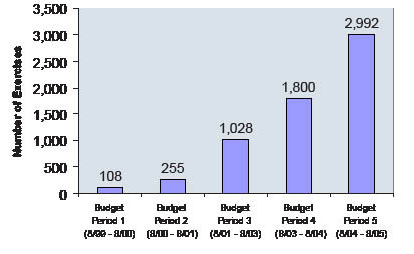

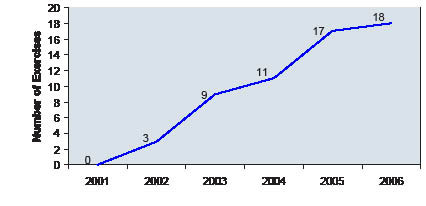

Exercising emergency response plans and validating training. Exercises test emergency response plans with personnel from across agencies and organizations.26 Exercises can provide valuable experience and knowledge because people, technology, and equipment are put into action to test their ability to respond. Figure 7 illustrates a steadily increasing number of exercises conducted by public health departments in the 50 states and DC. In addition, public health departments routinely evaluate exercises or real events and identify needed improvements. CDC specifically coordinates exercises with state and local public health departments to test plans for the receipt and distribution of the contents of the SNS. The number of CDC-coordinated SNS exercises has increased from 0 in 2001 to 18 in 2006 (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Public Health Preparedness Exercises, 50 States and DC, 1999-2005

Source: CDC, DSLR data; 1999-2005

26 Exercises provide opportunities to test capabilities and improve performance in a risk-free environment. The three types of exercises include tabletop exercises, which involve discussing responses to emergency scenarios and focus on training and problem solving; functional exercises, which test and evaluate capabilities and functions in responding to a simulated emergency, such as a disease outbreak; and full-scale exercises, which test and evaluate multi-agency, multi-jurisdictional coordinated response to an actual deployment of resources under crisis conditions as if a real incident had occurred.

27 CDC, DSNS Cities Readiness Initiative data; 2007

Challenges for Response

Ensuring public health uses an “all-hazards” approach to preparedness. Because of the many competing priorities for public health departments’ resources, being prepared to respond to a wide variety of emergencies remains a challenge. In 2006, all states and DC reported having plans covering biological agents, but fewer reported having plans covering radiation (43) or nerve agents (27).28

Retaining experienced public health response personnel. Ensuring that public health departments retain qualified response personnel is an ongoing challenge. A number of state and local agencies have difficulties retaining SNS coordinators.

Building and maintaining relationships.

To build and  maintain relationships with

response partners, public health professionals

need to continue planning and exercising with

other government agencies and the community.

Building these relationships requires other

responders to recognize the importance of public

health in emergency response. In 2006, most

states and DC reported having developed ICS

roles and responsibilities with hospitals (90%)

and local/regional emergency management

agencies (92%), but fewer (73%) had developed

them with federal emergency management

agencies.29

maintain relationships with

response partners, public health professionals

need to continue planning and exercising with

other government agencies and the community.

Building these relationships requires other

responders to recognize the importance of public

health in emergency response. In 2006, most

states and DC reported having developed ICS

roles and responsibilities with hospitals (90%)

and local/regional emergency management

agencies (92%), but fewer (73%) had developed

them with federal emergency management

agencies.29

Developing interoperable communication systems. Multiple agencies can work together more effectively during an emergency if all communication systems can “talk” to each other. In 2007, DHS reported that many cities and metropolitan areas have established multiagency communications, but more progress is needed to expand interoperable communication across jurisdictions and levels of government.30

Figure 8: Annual Number of Joint SNS Exercises to Test Response Plans, 50 States and DC, 2001-2006

Source: CDC, DSNS data; 2001-2006

Note: Figure 8 only includes joint state/CDC exercises. States also conduct exercises independently that are not

included in these numbers.

28 CDC, DSLR data; 2006

29 CDC, DSLR data; 2006

30 DHS, Tactical Interoperable Communications Scorecards: Summary Report and Findings; 2007

Exercises Prepared Public Health Response to a Meningitis Outbreak

When a meningococcal meningitis outbreak occurred at a local high school in Los Angeles, California, in 2006, the local public health department responded.

The public health department was ready because vaccination exercises had been conducted before the outbreak. The exercises provided public health department staff experience in working directly with the local and county law enforcement agencies, fire departments, and emergency medical services. This was valuable during the meningitis outbreak because collaboration resulted in effective site security, traffic control, and emergency medical technician response at the high school.

The County of Los Angeles Department of Public Health reported that “before, the setup and response to a disease outbreak took far longer, sometimes an entire day or more; site organization and management was often overwhelming, and at times chaotic.” A timely response reassured students and their parents that they were being well taken care of by the Department of Public Health during this outbreak.

Please refer to Section 2 for response examples for each state and directly funded locality.

Moreover, the report noted that some of the communications planning and exercises among response agencies did not include public health departments.

Monitoring environmental health. Environmental effects from an emergency, such as a chemical spill, need to be monitored over extended periods to track potential long-term health outcomes. In 2007, 11 states did not report any activities related to having systems that can track environmental exposures and adverse events over the long term.31

Helping at-risk populations during emergencies. CDC’s experience responding to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita showed that CDC and state public health departments must address the needs of at-risk populations in an emergency. For example, the elderly and others with chronic diseases need help to control diseases such as diabetes and heart conditions when health systems are not available.

31 CDC, DSLR Mid-Year Progress Report Review data; 2007

Get email updates

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Contact Us:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd

Atlanta, GA 30333 - 800-CDC-INFO

(800-232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348

24 Hours/Every Day - cdcinfo@cdc.gov