PUBLIC HEALTH PREPAREDNESS: MOBILIZING STATE BY STATE

Section 1: Public Health Preparedness in the States and DC

Public Health Laboratories

Improving Laboratory Testing for Biological and Chemical Threats, Communication, and Training

Public health laboratories are critical in identifying disease agents, toxins, and other health threats found in tissue, food, or other substances. They also play a large role in alerting others about emerging health threats, and training and supporting clinical laboratories. The cooperative agreement has funded public health laboratories to hire and train staff, and acquire equipment. This supports CDC preparedness goals in the areas of prevention, and detection and reporting.

Expanding testing. Public health laboratories have expanded their ability to perform rapid tests for biological and chemical agents. Previously, many state and local public health laboratories had to ship samples to CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for testing.

Now, as shown in Table 5, identification of biological agents (e.g., anthrax or plague) and chemical agents is possible through the Laboratory Response Network (LRN). The LRN is a national network of local, state, and federal public health laboratories; military, international, agricultural, and veterinary diagnostic laboratories; and food and environmental testing laboratories.

Table 5: Laboratory Testing Capabilities, 2001-2007

| Indicator | Then | Now (2007) | Percent Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| State and local public health laboratories that can detect biological agents | 83 (2002) | 110 | 33% |

| Public health laboratories that can test for and/or handle toxic chemical agents: | |||

| Level 1 laboratories* | 0 (2001) | 10 | - |

| Level 2 laboratories | 0 (2001) | 37 | - |

| Level 3 laboratories | 0 (2001) | 15 | - |

|

Source: CDC, DBPR LRN data; 2001-2007* Level 1 laboratories serve as surge capacity laboratories for CDC and can test for an expanded number of chemical agents, including nerve agents, mustard agents, and toxic industrial chemicals. Level 2 laboratories are also surge capacity laboratories but can test for a more limited panel of agents. Level 3 laboratories work with hospitals and other first responders within their jurisdiction to maintain competency in clinical specimen collection, storage, and shipment. |

|||

Laboratory Response Network

Some of the ways CDC supports LRN member laboratories include:

- Sharing tests used to confirm biological and chemical agents;

- Enabling secure communications on emerging and emergency issues;

- Developing training curricula;

- Implementing a quality assurance program; and

- Providing vaccines to protect laboratory workers from dangerous agents.

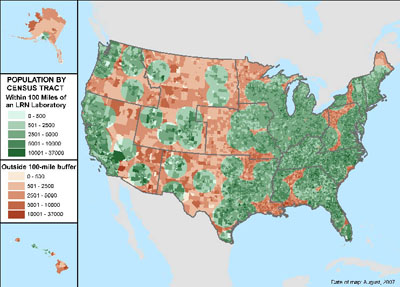

This network supports the laboratory facilities and trained staff to respond to biological and chemical terrorism and other public health emergencies. In 2007, the LRN had 163 member laboratories capable of detecting biological agents (of which 110 are state and local public health laboratories). In addition, 62 LRN laboratories can test for and/ or handle chemical agents. As shown in Figure 3, 90% of the U.S. population lived within 100 miles of a LRN laboratory in 2007.14

Improving communication among laboratories. Once a threat is confirmed in one laboratory, other laboratories need to be quickly alerted since they might receive related case samples (indicating that the threat is spreading). To enable this communication, CDC manages a secure communication system among LRN member laboratories. In addition, public health laboratories need to communicate with the thousands of clinical and commercial laboratories

Figure 3: U.S. Population within 100 Miles of a LRN Laboratory, 50 States and DC, 2007

Source: CDC, DBPR LRN data; 2007

Communication among laboratories and public health departments is key, as outbreaks identified in one location can also be present in others. monitoring health through routine testing. These laboratories serve as early alert systems and can be the first to confirm a potential health threat. All states now have public health laboratories that can communicate rapidly with these laboratories (Table 6).

Table 6: Laboratory Communications, 2001-2006

Communication among laboratories and public health departments is key, as outbreaks identified in one location can also be present in others.

| Indicator | Then (2001) | Now (2006) | Percent Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| States with public health laboratories that could communicate with clinical and commercial laboratories (through email or fax to multiple recipients) | 201 | 512 | 155% |

|

1 APHL, Public Health Laboratory Issues in Brief: Bioterrorism Capacity; published October 2002 - data for 46 states

and DC 2 APHL, Public Health Laboratory Issues in Brief: Bioterrorism Capacity; published May 2007 - data for 50 states and DC |

|||

Training laboratory staff. Expanding training for clinical laboratory workers is key because they are often the first to confirm diseases leading to public health threats. In 2002, state public health laboratories offered 65 classes to fewer than 3,000 clinical laboratory scientists on testing for biological agents; while in 2006, states offered 500 classes to more than 8,000 laboratory scientists.15

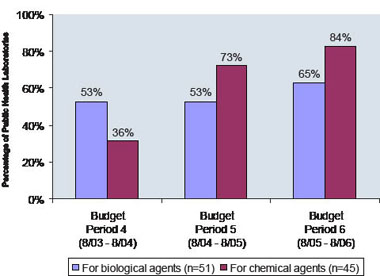

Public health laboratories also need to conduct exercises to practice emergency response protocols. Figure 4 shows the increasing number of state public health laboratories conducting exercises to handle Category A biological agents (high-priority agents that pose a risk to national security) and chemical agents (toxic substances such as cyanidebased compounds, heavy metals, and nerve agents). Refer to Appendix 6 for a list of Category A and B biological agents.

Figure 4: Public Health Laboratories Conducting at Least One Exercise for Biological and Chemical Agents, 2003-2006

Source: CDC, DSLR data; 2003-2006 Note: Data for chemical terrorism agent exercises were collected for Level 1 and Level 2 laboratories. 15 APHL, unpublished data; 2002 and 2006

Joint laboratory and epidemiology investigations are critical for a rapid response to disease outbreaks.

Coordinated Public Health Response Rapidly Identifies the Source of E. Coli Outbreak

The public health response to a 2006 outbreak of E. coli infections showed how cooperative agreement funding has improved states’ ability to respond. The response to the outbreak highlighted the importance of collaboration and communication among public health professionals in the 26 affected states.

In September 2006, state public health departments began investigating an outbreak of infections caused by E. coli O157:H7, a dangerous foodborne bacterium, to determine who the outbreak was affecting and how patients had contracted the infection. Public health professionals interviewed both ill and unaffected individuals to identify the source of the outbreak and determined that pre-packaged fresh spinach was the likely cause.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advised consumers not to eat fresh spinach, and CDC sent messages out to the public health community via the Health Alert Network (HAN) and Epi-X to alert them of a nationwide outbreak. Federal and affected state health public information officers quickly disseminated and updated critical health information about the outbreak to public health partners, clinicians, and the news media.

Meanwhile, state public health laboratories performed DNA “fingerprinting” tests, or pulsedfield gel electrophoresis (PFGE), to distinguish strains of E. coli. Laboratories submitted information about these strains to PulseNet, a national network of laboratories coordinated by CDC that consists of state and local public health departments and federal agencies (CDC, FDA, and USDA). Through PulseNet, public health professionals across the country could compare the DNA fingerprints to determine if their state had cases of E. coli related to the outbreak. PulseNet confirmed the outbreak in multiple states.

Public health departments and laboratories in 10 states isolated E. coli strains from bags of spinach retrieved from patient households and performed tests to match these to E. coli strains isolated from patients. Local, state, and federal health officials collaborated to identify and report cases, communicate with consumers, and identify the FDA, USDA, and California public health professionals visited selected farms, tracing the bacteria to the source.

Rapid identification of the bacterium causing the outbreak and tracking to the food source resulted in a nationwide recall of fresh spinach products. Joint laboratory and epidemiology investigations were critical for this rapid response.

Please refer to Section 2 for response examples for each state and directly funded locality.

Challenges for Public Health Laboratories

Boosting the laboratory scientist workforce to ensure rapid and accurate testing. In a 2007 APHL survey, 31 state public health laboratories reported difficulties recruiting qualified laboratory scientists. Moreover, 39 reported needing additional staff to perform polymerase chain reaction, a rapid DNA testing technique to quickly identify bioterrorism agents.16 This reflects a nationwide shortage of highly skilled laboratory workers to confirm potential health threats.

Ensuring secure electronic communication. Although 44 state public health laboratories have Laboratory Information Management Systems supporting laboratory functions, 19 of those laboratories cannot send or receive electronic messages that meet CDC standards for exchanging, communicating, and protecting data.17 Without such electronic communication, it is impossible to rapidly monitor and integrate laboratory test results at the national level during an emergency.

Broadening the range of laboratory testing. States vary in the extent to which they can test for biological and chemical agents. For instance, all states have at least one laboratory that can test for the biological agents that cause anthrax, bubonic plague, tularemia, and brucellosis, but eight are not able to test for the highly infectious agent that causes Q fever.18 For chemical agents, 9 states can test for blistering agents (such as mustard gas); 13 states for volatile organic compounds (chemicals such as benzenes, which can have short- and long-term health effects); 28 states for nerve agents (including manmade chemical warfare agents such as sarin or VX nerve agent); and 30 states for blood metals (such as mercury and lead).19

Although state public health laboratories can test for biological and chemical agents in blood or urine, they cannot test for chemical agents outside of these human clinical samples, such as in an unknown white powder. Laboratories are also limited in their ability to rapidly test large quantities of samples for chemical agents.

Another challenge is that no state public health laboratory can rapidly identify priority radioactive materials in clinical samples.20 This could delay medical treatment decisions when a possible radiological exposure has occurred.

16 APHL, Public Health Laboratory Issues in Brief: Bioterrorism Capacity; published in May 2007 - data for 50 states and DC

17 APHL, Public Health Laboratory Issues in Brief: Bioterrorism Capacity; published in May 2007 - data for 50 states and DC

18 CDC, DBPR LRN data; 2007

19 CDC, National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH) data; 2007

20 CDC, NCEH data; 2007

Get email updates

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Contact Us:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd

Atlanta, GA 30333 - 800-CDC-INFO

(800-232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348

24 Hours/Every Day - cdcinfo@cdc.gov