Simple "Market Research" Strategies

Learning the needs, desires, and preferences of the target audiences does not need to be time consuming. Whether this learning takes place at the water cooler or from a marketing consultant, the point is to know your audience. Below are some of the many ways to learn from and about the people and organizations considered partners in state plan development, as well as those who will use and implement the plan.

| Telephone Strategies |

Face-to-Face Strategies |

Electronic Strategies |

| Brief, informal calls to partners |

Conduct face-to-face interviews with key partners |

Email or post requests for ideas |

| Structured conference calls with groups or individuals |

Hold structured discussions at scheduled association, staff, or community group meetings |

Research known audience perspectives, exposure to similar initiatives, and communication preferences |

| Telephone surveys Telephone focus groups |

Convene focus groups |

Put draft materials or surveys on the web for feedback |

Sample "Market Research" Questions

Carefully designed questions will help focus learning on the most important areas. The right questions will depend upon the audience, project goals, level of input desired and the stage in the 2010 planning process. For example, if the steering committee and work groups were already formed, planners would focus questions on how to develop and implement the plan rather than how to engage key partners and the community in the planning process.

|

Planning Process

- How does your organization participate in planning processes?

- What kinds of organizations have approached you to be a part of an advisory committee? How do you choose which ones you will join?

- If you were inviting others (members of the target audience) to attend a work group meeting for this project, what would you say to get them to come? What would you avoid saying?

- What was your impression of the state's year 2000 planning process? What worthwhile came out of it?

- Tell me about a good experience that you have had working with public health.

|

Design and production

- What makes a plan useful? What kinds of plans are not useful?

- If you need detailed information about a topic, do you prefer to have it included at the back of a publication, in a separate publication, or on a web site?

- Which of these formats is easy to use (present two or more visual formats)?

- What do you think the people who wrote this page want you to do?

|

|

Marketing

- Where do you get ideas for your work or community activities?

- What kinds of published recommendations and plans have you seen from other state agencies?

- What impression do you have of government planning efforts?

- When you receive plans from other agencies, what do you do?

- If you were in charge of marketing the state's health plan to others (members of the target audience), what would you do?

- What do you read?

- How do you like to get information about emerging objectives in public health?

|

Implementation

- What makes a healthy community?

- How do you contribute to your community’s health? In what areas would you like to do more?

- Have you ever used another agency’s plan or objectives in your own work? What was the most important factor in your decision?

- How important are goals and plans to your daily work? What would be an incentive to tie your program activities to the state health objectives?

- What would it take for you to commit to help achieve a state health objective?

- If your supervisor asked you about how you used the state’s year 2000 objectives, what would you say?

|

How to Develop a Marketing Plan

A marketing plan clarifies how a state can share the HP 2010 vision with others, promote the published plan, and "make things happen." To develop marketing goals and objectives, planners must determine priority audiences, desired results, key messages, strategies and tactics, and marketing partners.

1. Priority audiences

Whose opinions or actions are most important to the success of the HP 2010 process and the implementation of objectives? Identify potential target audiences and choose two to three of most importance.

Sample Target Audiences for 2010 Marketing Plans:

- Policymakers, including elected officials

- Private sector health organizations, including managed care organizations

- Private sector employers

- Medical societies and other health professional associations

- School and education leaders

|

- State voluntary organizations with local affiliates

- Public health leaders and program managers

- Front-line public health staff

- Grass roots groups with the capacity to address health objectives

- Potential community advocates for priorities

|

2. Desired Results

What do you want each target audience to do or believe? Be specific! The final 2010 plan and marketing materials should, explicitly or subtly, be designed to achieve the desired outcome.

As examples, you might want the target audience to…

|

(do)

…use the state's 2010 objectives to develop policies to improve public health infrastructure

…use objectives and recommendations in the 2010 plan to evaluate proposed legislation relevant to focus areas

…incorporate components of the plan into agency strategic plans

…commit resources and staff to develop new data sources |

(believe)

…be eager to work toward achieving objectives in their communities

…support the planning and evaluation role of public health

…believe the plan boosts accountability

…feel personal responsibility to be healthier for a healthy state

…think the 2010 priorities are fair

…believe that state and local resources should be tied to objectives |

3. Key Messages

For each audience, what are the main messages to communicate? Perhaps your main message is that this is a "people’s plan," a governor’s plan, a call to action, or a measure of the current path to success. Whatever your message, be sure to identify key words and phrases that support it. If your market research has identified that your target population responds favorably to "milestones," "action plans," and "steps to success" but responds unfavorably when it hears "objectives" or "benchmarks" include the preferred words in your key messages. Remember to be consistent with vocabulary. Key messages should be reinforced in all communications about the plan, including slogans, conference presentations, press releases, and executive summaries.

4. Marketing Strategies and Tactics

How will you reach each audience?

Strategies describe your general marketing approach. For some audiences and purposes, the best strategy may be to blanket the audience with messages about 2010 in a short period of time. For others, your strategy might be to selectively promote 2010 in connection with timely events (e.g., budget hearings) over several years.

Tactics are the methods of communication, such as:

- posters

- television ads

- newspaper articles, editorials

- conference booths

- training and presentations

- letterhead

|

- bumper stickers

- fax or electronic newsletters

- individual meetings

- brochures

- calendars

- web sites

|

Assess the communication environment of the target audience. The way to reach policy makers may be through their staff or targeted newsletters, whereas the way to reach public health program managers may be through an annual conference or posters at work. List marketing strategies with a budget in mind. However, a longer menu of marketing options can help identify marketing opportunities and resources in the future.

5. Marketing Partners

General media, special interest media, advocacy organizations, public relations offices, health education units, graphics departments, private health care organizations, and professional organizations with newsletters or web sites may be excellent partners in promoting year 2010 objectives. Healthy People steering committees may include many potential marketing partners who have experience with campaigns and already have an interest in promoting the 2010 plan.

Exclusive arrangements with a few marketing partners who are committed (e.g., "Channel 12 Cares") may sometimes be more effective than multiple, less focused partners. Explore options with marketing professionals and check your agency policies.

Evaluate Your Marketing Plan

Just as a marketing plan can clarify how a state can share the HP 2010 vision with others, the marketing evaluation plan can identify whether efforts were effective. The following factors can be used throughout the process internally as well as periodically be posed to the target audience throughout the decade.

- Was the planning process effective in preparing the marketing goals and action plan?

- Was there timely follow-through on marketing activities such as information requests?

- Is the marketing strategy a clear representation of the primary vision of the state plan?

- Is the marketing plan sensitive to the community’s cultural dynamics?

- Did the development process include input from a diverse group of people?

- Were various media employed effectively to promote the state plan’s goals, actions, and accomplishments? Was there media coverage (e.g., newspaper articles)? Did associations and other community partners use the logo, articles, or other marketing materials in their communications?

- How was input from partners used in developing and refining the marketing plan?

- Through what mechanisms was input collected (e.g., surveys, focus groups, consultants)?

- Has the marketing process assisted progress in meeting the state plan’s specific objectives?

- How does the marketing plan mirror the goals and objectives of the overall state’s plan?

- Has marketing generated funding or other resources for the initiative?

- Were messages designed to clarify what audiences should do with the state plan or what they should believe? Were marketing messages clear to targeted audiences?

- Did marketing efforts meet state objectives to influence the actions or beliefs of target audiences? (e.g., Did policy makers propose or pass legislation based on or using the state plan?)

Oral Health

Today about half of all Vermont elementary school students and one-third of high school students are cavity-free. Still, sine dental decay and gum disease are both largely preventable, there is ample room for improvement. With the best dental care and personal oral health habits, most people should be able to keep their teeth for a lifetime.

Today about half of all Vermont elementary school students and one-third of high school students are cavity-free. Still, sine dental decay and gum disease are both largely preventable, there is ample room for improvement. With the best dental care and personal oral health habits, most people should be able to keep their teeth for a lifetime.

Objective 1

Fluoridate the Water Supply

Every dollar spent on community water fluoridation saves $80 in dental care costs. Since it was introduced in the 1940s, water fluoridation has been consistently demonstrated to be safe and effective. In communities that add fluoride to their drinking water, children have a 20 to 40 percent lower rate of cavities. Tooth decay among adults decreases by a similar percentage.

Objectives 2-3-4

Regular Dental Care

Regular dental checkups, that include professional cleaning and evaluation for early signs of tooth decay and gum infection, have been proven to be effective in maintaining oral health. However, many people do not seek care. 1995 survey found that the two most common reasons Vermonters give for not visiting a dentist are "no reason to go" and "cost." Even people with dental health insurance may not get regular care. In 1998, only 25 percent of adults and 46 percent of children with Medicaid coverage were receiving regular dental care.

Objective 5

Increase Use of Dental Sealants

May studies have shown that with the use of sealants and fluoride, tooth decay can be virtually eliminated. Placing sealants (plastic coatings applied to the tooth biting surface) on permanent molar teeth shortly after they come in protects the teeth from bacteria that cause tooth decay.

Objective 6

Tobacco Counseling by Dentists

Dentists and dental hygienists have a unique opportunity to influence their patients about tobacco use. Dentists often see adolescents and young adults at regular intervals, around the time when smoking begins and becomes a habit. A clinical trial has shown dentists to be effective counselors in getting their patients to quit smoking.

Oral Health Objectives

Objective 1. Increase the percentage of the population served by community public water systems that receive optimally fluoridated water.

| Goal |

75% |

| VT 1999 |

69% |

| US 1992 |

62% |

Objective 2. Further reduce the percentage of children (age 6-8) with untreated dental decay in primary and permanent teeth.

| Goal |

21% |

| VT 1993-94 |

19% |

| US 1988-94 |

29% |

Objectives 3. Reduce the percentage of youth (age 14-15) with untreated dental decay.

| Goal |

15% |

| VT 1993-94 |

22% |

| US 1988-94 |

20% |

Objective 4. Increase the percentage of people who use the dental system each year.

| Goal |

83% |

| VT 1999 |

74% (age 18+) |

| US 1997 |

56% (age 2+) |

Objective 5. Increase the percentage of children who receive sealants--

at age 8:

| Goal |

50% |

| VT 1993-94 |

43% |

| US 1988-94 |

23% |

at age 14:

| Goal |

50% |

| VT 1993-94 |

45% |

| US 1988-94 |

15% |

Objective 6. Increase the percentage of dentists who counsel patients about quitting smoking.

| Goal |

85% |

| Vermont survey under development |

| US 1997 |

59% |

Formatting Press Releases

(use 8 ½ x 11 letterhead, double spaced text)

Release date and time

Name of contact person

Email address

Phone #

Headline (short--one line if possible, concise and eye-catching)

Dateline (where the news originates)---Start text here for lead paragraph. Usually only 1-2 sentences to encapsulate the main idea and tell the reader why they should care about the issue.

Second paragraph should expand on the lead, if necessary, and maybe include a comment from someone regarding the importance of the news, event, report finding, etc.

Body of the press release should include:

- background/history of the issue

- description of study methods or other relevant info

- a summary of the findings, etc.

- conclusion that is a summary statement or closing comments from someone

- source of funding for project, research, etc if not mentioned before.

Try to keep to one page, but include the most important information in first 1-2 paragraphs.

Use subheads if it helps focus the reader.

# # # (indicates end)

if more than one page, signify by "more" and number pages

Communication Channels and Activities: Pros and Cons

| Type of Channel |

Activities |

Pros |

Cons |

| Interpersonal Channels |

- Hotline counseling

- Patient counseling

- Instruction

- Informal discussion

|

- Can be credible

- Permit two-way discussion

- Can be motivational, influential, supportive

- Most effective for teaching and helping/caring

|

- Can be expensive

- Can be time-consuming

- Can have limited intended audience reach

- Can be difficult to link into interpersonal channels; sources need to be convinced and taught about the message themselves

|

| Organizational and Community Channels |

- Town hall meetings and other events

- Organizational meetings and conferences

- Workplace campaigns

|

- May be familiar, trusted, and influential

- May provide more motivation/support than media alone

- Can sometimes be inexpensive

- Can offer shared experiences

- Can reach larger intended audience in one place

|

- Can be costly, time consuming to establish

- May not provide personalized attention

- Organizational constraints may require message approval

- May lose control of message if adapted to fit organizational needs

|

Mass Media Channels

Newspapers |

- Ads

- Inserted sections on a health topic (paid)

- News

- Feature stories

- Letters to the editor

- Op/ed pieces

|

- Can reach broad intended audiences rapidly

- Can convey health news/breakthroughs more thoroughly than TV or radio and faster than magazines

- Intended audience has chance to clip, reread, contemplate, and pass along material

- Small circulation papers may take PSAs

|

- Coverage demands a newsworthy item

- Larger circulation papers may take only paid ads and inserts

- Exposure usually limited to one day

- Article placement requires contacts and may be time-consuming

|

| Radio |

- Ads (paid or public service placement)

- News

- Public affairs/talk shows

- Dramatic programming (entertainment education)

|

- Range of formats available to intended audiences with known listening preferences

- Opportunity for direct intended audience involvement (through callin shows)

- Can distribute ad scripts (termed "live-copy ads"), which are flexible and inexpensive

- Paid ads or specific programming can reach intended audience when they are most receptive

- Paid ads can be relatively inexpensive

- Ad production costs are low relative to TV

- Ads allow message and its execution to be controlled

|

- Reaches smaller intended audiences than TV

- Public service ads run infrequently and at low listening times

- Many stations have limited formats that may not be conducive to health messages

- Difficult for intended audiences to retain or pass on material

|

| Television |

- Ads (paid or public service placement)

- News

- Public affairs/talk shows

- Dramatic programming (entertainment education)

|

- Reaches potentially the largest and widest range of intended audiences

- Visual combined with audio good for emotional appeals and demonstrating behaviors

- Can reach low income intended audiences

- Paid ads or specific programming can reach intended audience when most receptive

- Ads allow message and its execution to be controlled

- Opportunity for direct intended audience involvement (through call-in shows)

|

- Ads are expensive to produce

- Paid advertising is expensive

- PSAs run infrequently and at low viewing times

- Message may be obscured by commercial clutter

- Some stations reach very small intended audiences

- Promotion can result in huge demand

- Can be difficult for intended audiences to retain or pass on material

|

| Internet |

- Web sites

- E-mail mailing lists

- Chat rooms

- Newsgroups

- Ads (paid or public service placement)

|

- Can reach large numbers of people rapidly

- Can instantaneously update and disseminate information

- Can control information provided

- Can tailor information specifically for intended audiences

- Can be interactive

- Can provide health information in a graphically appealing way

- Can combine the audio/visual benefits of TV or radio with the self-paced benefits of print media

- Can use banner ads to direct intended audience to your program's Web site

|

- Can be expensive

- Many intended audiences do not have access to Internet

- Intended audience must be proactive -- must search or sign up for information

- Newsgroups and chat rooms may require monitoring

- Can require maintenance over time

|

Adapted from: DHHS, PHS, NCI: Making Health Communications Programs Work.

Scientific Information, Simply Put

Text Appearance

The way your text looks can greatly affect readability. Follow these simple tips:

- Use font sizes between 12 and 14 points.

- Anything less than 12 points can be too small for many audiences. Older people and people who have trouble reading may need larger print. Use a font size at least 2 points larger than the text size for headings.

Example of font sizes:

This is 8 point.

This is 10 point.

This is 12 point.

This is 14 point.

This is 16 point.

This is 18 point.

- For the body of the text, use fonts with serifs, like the one used in this line. (Serifs are little ‘feet’ on the letters.)

- Fonts without serifs (sans serifs), like the one used in this line, are harder to read. Limit sans sarifs fonts to headings and subheadings.

- Do not use

or

or  lettering.

lettering.

- Mix upper and lower case letters (like in this line). ALL CAPS ARE HARDER TO READ.

- Use bold face or underlining to emphasize words or phrases. Limit using italics.

- Use dark letters on a light background. Light text on a dark background is harder to read.

Source: Text Appearance: pg 9, Visuals: pgs 11-16, Layout and Design: pgs17-20, Tips on Translation: pgs. 21-22, Checklist for Easy-to-Read, Print Materials: pgs 29.

Visuals

Visuals can enhance your materials when used correctly. This section provides 5 steps to help you choose effective, appealing visuals.

1. Use visuals to help communicate your messages.

- Present one message per visual.

- When you show several messages in one visual, readers may miss some or all of the message.

- Create visuals that help emphasize or explain the text. Steer clear of visuals that decorate your materials or are very abstract.

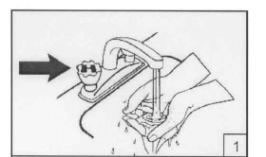

For example: Images A and B are illustrations for the cover of a brochure on what to do if you get hurt on the job at a construction site. Image A, and abstract image for first aid, does not enhance meaning. But image B, which shows two workers using a first ad kit, clearly relates to the subject of the brochure -- and it shows an action the brochure will discuss.

- Show the actions you want your readers to take. Avoid images that show what the reader should not do.

For example: If you are telling reader to choose healthy snacks, such as fruit, instead of sweets and junk food, image A is more affective because it shows readers what to eat. It reinforces your message. Image B shows readers what they should not eat, but it gives them no visual link to what they should eat. Also, some cultures do not understand wand and "X" through an item means "no."

2. Choose the best type of visual for your materials.

- Photographs may work best for depicting "real life" events, showing people, and conveying emotions.

- If you use photos, be sure that materials in the background will not distract your reader.

- Simple illustrations or line drawings may work best for showing a procedure (drawing blood), depicting socially sensitive issues (drug addicts), and explaining an invisible or hard-to-see situation (airborne transmission of TB).

- Use simple drawings and avoid unnecessary details. Steer clear of abstract illustrations that could be misinterpreted.

- Cartoons may be good to convey humor or set a more casual tone.

- Use caution with cartoons; not all audiences understand them or take them seriously

Pretesting visuals with your target audience will help you decide which type is best.

3. Make visuals culturally relevant and sensitive.

Use images and symbols familiar to your audience.

Use images and symbols familiar to your audience.

For example: Not all cultures understand that this image means "no smoking".  If you show people in your visuals, make them of the same racial or ethnic group as your target audience.

If you show people in your visuals, make them of the same racial or ethnic group as your target audience.

- Choose clothing styles that your target audience would wear. For materials designed for diverse audiences, show people from a variety of ethnic, racial and age groups.

For example: You might use a drawing like this one if your audience were Indian women.

4. Make visuals easy for your reader to follow and understand.

- Place illustrations near the test to which they refer.

For example: if you place a drawing in the top, right-hand corner that related to the text found in the lower left-had corner, readers may not connect the drawing thy out written message.

- Use brief captions that include your key message.

For example: From the caption, the reader knows exactly what the visual is trying to convey. The caption also repeats a sentence found in the body of the document, which helps to reinforce the message.

Wear gloves to avoid spreading disease.

Wear gloves to avoid spreading disease.

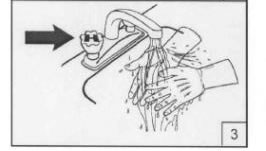

- When showing a sequence, number the images.

For example:

| 1. Wet hands with warm water. |

|

| 2. Rub hands together with soap for 10-15 seconds. |

|

| 3.Rinse off all of the soap using warm water. |

|

- Use cues like arrows and circles to point out key information in your visuals.

For example: The image below is for a brochure on how to avoid injuries at a construction site. The arrow directs readers to the hard hat, the most important item in the drawing.

| Always wear a hard hat at the job site. |

|

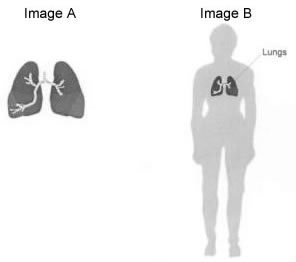

5. When illustrating internal body parts or small objects, use realistic images and place them in context.

- When showing internal body parts, include the outside of the body.

- Avoid cutting off body parts.

For example: Without showing the body for context, readers may not know what Image 1 is. Image 2 is much more clear.

- Do not use cartoon-like drawings of body parts or other health related images.

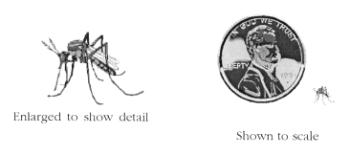

- Draw small objects larger to show detail, but also show to scale compared to something familiar to your audience.

For example: The mosquito below is drawn several times larger than the actual size to show readers what it looks like. Then it is shown next to a penny so readers can see how big it really is.

6. Use only professional, adult looking visuals.

- Avoid poor quality visuals.

- They make your messages less credible. And adults may not even pick up your material if they contain childish or "cutesy" visuals.

Layout and Design

You can present your information and visuals in ways that make your materials easier to read and more appealing to your audience. Here are 4 ideas.

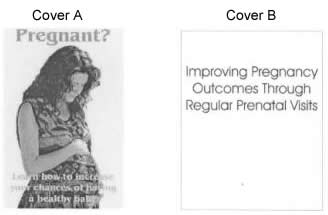

1. Design an effective cover.

- Make the cover attractive to your target audience.

- If the cover does not include images and colors your intended readers like, they may not pay attention to it.

- Show the main message and target audience on the cover.

- Readers should be able to grasp your main idea just by looking at the cover.

For example: Cover A is much more effective than Cover B in getting the attention of your audience (pregnant women) and in telling readers what they can expect to find inside.

1. Organize your messages so they are easy to act on and recall.

- Present a complete idea on one page or two facing pages.

- If readers have to turn the page in the middle of your message, they may forget the first part of the message.

- Place the most important information at the beginning and end of the document.

- The best method is to state your main message first thing, expand on your message in the middle of the document, and repeat the main message at the end.

- Organize ideas in the order that your target audience will use them.

For example: In a brochure about what to do if you find a chemical spill, tell readers to 1) leave the area right away, 2) note the location of the spill, 3) report it to the police or fire department, and 4) warn others to stay away from the area.

- Use headings and sub-headings to "chunk" text.

Questions often work well as subheadings. Readers can skim the questions to see which ones apply to them or are of greatest interest. And questions can make your materials seem interactive.

Leave more space above headings and subtitles than below them. This gives stronger visual link between the heading and the text that follows.

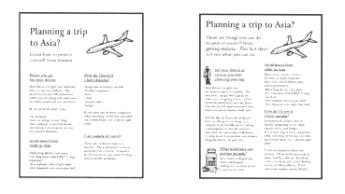

3. Leave lots of white space.

- Leave at least ½ inch to 1 inch of white space around the margins of the page and between columns.

- Limit the amount of text and visuals on the page.

For example: The document on the left is easier to read than the one on the right because is has more white space and just one visual.

4. Make the text easy for the eye to follow.

- Break up the text with bullets.

For example: The bullets used in the example on the left make the items in the list easier to read than in the paragraph on the right.

|

Children should get these shots by age 2:

- measles/mumps/rubella

- Haemophilus influenzae type b

- Polio

- Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis

- Hepatitis B

- Varicella

|

By age 2, children should get shots against Measles/mumps/rubella; Haemophilus influenzae type b; polio; diphtheria; tetanus, pertussis; hepatitis B; and varicella. |

- Do not justify the right margin.

- Right justified margins cause an uneven spacing between words. Uneven spacing can confuse unskilled readers. Compare the samples below.

|

Sample 1

This column does not have a right-justified margin. The spaces between words are even. The jagged edge also makes it easer to distinguish one line form the others. |

Sample 2

This column has right-justified margins. The spaces between words are uneven and the lines are all the same length. This can confuse readers, especially unskilled readers, and make it harder to differentiate one line from the others. |

- Use columns.

- Columns with line lengths of 40-50 characters are easiest to read. Compare paragraphs A, B, and C below.

|

Paragraph A

This column is only 20-25 characters long and is hard to read. Your eye jumps back and forth too much and gets tired quickly.200 |

|

Paragraph B

This column is the best length. It is 40-50 characters long. Your eye can return to the beginning of the next line easily, and it doesn’t jump back and forth very much. Try to design your materials with columns like this one. |

|

Paragraph C

This paragraph is hard to read, especially for unskilled readers, because the lines are so long. After reading only line, the eye has to move back across the entire page to find the start of the next line. Paragraphs that run across the whole page also look very dense and don’t allow for much white space on the page. |

Place key information in a text box..

Place key information in a text box..

- Text boxes make it easier for your reader to find the most important information on the page.

For example: The eye is drawn to the shaded box on the sample page on the right.

Tips on Translation

While it is best to develop your materials in the language of your target audience, translating them from English (or another language) is often all you have time or resources for. This section will help you ensure that translations of your materials are both culturally and linguistically appropriate.

Remember. Messages that work well with an English-speaking audience may not work for audiences who speak another language.

Find out about your target audience's values, health beliefs, and cultural perspectives. You can do this by conducting focus groups or other kinds of audience research.

Design material for minority populations based on subgroups and geographic locations.

All members of a minority population are not alike. Mexican Americans, for example, may respond differently than Cuban Americans to certain words, colors, and symbols. Likewise, Korean women living in New York City may view a health issue very differently from Korean women living in Los Angeles.

Get advice from community organizations in the areas you wish to reach.

Local groups that work regularly with your target audience can give you valuable insight about your audience. They can also recruit participants for focus group testing and help you gain the trust of your audience.

Carefully select and instruct your translator.

Hire a translator who knows a lot about your target audience and has translated many types of documents. Tell your translator the purpose of the materials, the appropriate reading level, and the main messages to convey. Review any medical or technical terms the translator does not know.

Avoid literal translation.

Allow your translator to select from a wide range of expressions, phrases, and terms used by the target audience. This flexibility will result in more culturally appropriate material.

Use the back-translation method.

Once the material has been translated to the target language, translate it back to English. (This step should be done by someone other than the original translator.) This will make sure the meaning and tone of the message have stayed the same.

Field test draft materials with members of the target audience.

This step will allow you to get feedback from your actual readers and to make changes based on their comments and suggestions.

Avoid these common pitfalls:

- Do not translate English slang phrases or idioms literally.

- Do not translate into a dialect unless it is used by your target audience.

- Do not omit accents-make sure your word processing and desktop publishing software have all the accents used in your target language.

Note: If you list a phone number to call for more information, make sure staff fluent in the target language are available during business hours (or around the clock if on a 24-hour hotline). You will frustrate your readers if they cannot reach someone who is fluent in their language at the phone number they were given. This can undermine your overall communication efforts.

Appendix A

Checklist for Easy-to-Read Print Materials

- Have you limited your messages to 3-4 per document (or section)? Have you left out information that is "nice to know" but not necessary?

- Is the most important information at the beginning of the document, and repeated at the end?

- Have you identified action steps or desired behaviors for your audience?

- Is information presented in an order that is logical to your audience?

- Is information chunked, using headings and subheadings? Do lists include bullets?

- Is the language culturally appropriate? And the visuals?

- Have you eliminated as much jargon and technical language as possible? Is technical or scientific language explained?

- Have you used concrete nouns, active voice, and short words and sentences? Is the style conversational?

- Is the cover attractive to your target audience? Does it include your main message?

- Are your visuals simple and instructive rather than decorative? Do they help explain the messages found in the text?

- Are your visuals placed near related text? Do they include captions?

- Does your document have lots of white space? Are margins at least 1/2 inch?

- Is the print large enough (at least 12 points) and does it have serifs?

- Have you used bold, underlining, and text boxes to highlight information? And avoided using all capital letters?

- Is text justified on the left only? Did you use columns?

References: Promoting HP 2010 Oral Health Plans and Activities

Adler EW. Everyone’s Guide to Successful Publications. Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press. 1993.

AMC Cancer Research Center. Beyond the Brochure. Alternative Approaches to Effective Health Education. Denver, CO: AMC Cancer Research Center. 1994.

Anderson AR. Marketing Social Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 1995.

Berland GK, et al. Health information on the Internet: Accessibility, quality and readability in English and Spanish. JAMA. 285(20):2612-21, 2001.

Bolig R. Social marketing and health communications. A J Health Communications. Spring:12-16, 1997.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scientific and Technical Information. Simply Put. 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: CDC. 1999.

Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. Advancing the Healthy People 2010 Objectives through Community-Based Education: A Curriculum Planning Guide. San Francisco, CA: CCPH. 2003. (Order form available online at http://www.futurehealth.ucsf.edu/).

Edmunds M, and Fulwood C. Strategic communications in oral health: Influencing public and professional opinions and actions. Ambulatory Pediatr. 2(2 -- Supp):180-184, 2002. (Earlier version available online at www.cdhp.org/) Oral Health Publications/Oral Health Policy.

Institute of Medicine. Speaking of Health: Assessing Health Communication Strategies for Diverse Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2002. (www.nap.edu)

McKinney J and Kurt-Resi S. Culture, Health and Literacy. A Guide to Health Education Materials for Adults with Limited English Literacy Skills. Boston, MA: World Education. 2000.

NCI. Making Health Communication Programs Work: A Planners Guide. Bethesda, MD: NCI. 2002. (Available online at www.cancer.gov/pinkbook. Print or CD-ROM copies can be ordered online at http://cancer.gov/publications or by calling 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237)).

NIH. A Guide for Making Print Documents Accessible to Persons with Disabilities. Bethesda, MD: NIH, NIAMS. 1995.

Public Health Foundation. Communicating Health Goals and Objectives. (In Healthy People 2010 Toolkit. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation. 1999. (available online at http://health.gov/healthypeople)

Siege M and Doner L. Marketing Public Health: Strategies to Promote Social Change. Baltimore, MD: Aspen Pub. 1998.

Sorien R and Baugh T. Power of information: closing the gap between research and policy.

Health Aff (Millwood). 21(2):264-73, 2002.

USDHHS. Annotated Bibliography. Effective Dissemination of Health and Clinical Information to Consumers. Rockville, MD: USDHHS, AHCPR. 1995.

USDHHS. Chapter 11. Health Communication. (In Healthy People 2010, Vol I.,. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Govt Printing Office. 2000.) (www.health.gov/healthypeople/Document/tableofcontents.htm#volume1)

Wallach L and Dorfman L. Media advocacy: A strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Ed Quarterly. 23(3)L293-317, 1996.

Wallach L et al. Media Advocacy and Public Health: Power for Prevention. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. 1993.

Warren RC. Oral Health for All: Policy for Available, Accessible and Acceptable Care. Washington DC: Center for Policy Alternatives, 1999 (available online at www.stateaction.org).