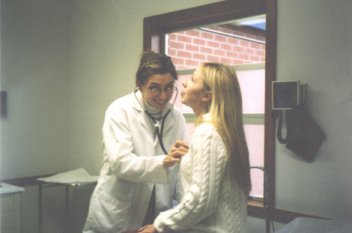

Nurse Practitioner Brings Health Care Home in Idaho

Margaret Mortimer, M.S.N., has “adopted” some of her patients with special needs who live in isolated stretches of southern Idaho. When those patients are unable to come to the Glenns Ferry Community Health Center (CHC) where she works, Mortimer drives the back roads to make home visits in order to ensure they receive the treatment they need.

Margaret Mortimer, M.S.N., has “adopted” some of her patients with special needs who live in isolated stretches of southern Idaho. When those patients are unable to come to the Glenns Ferry Community Health Center (CHC) where she works, Mortimer drives the back roads to make home visits in order to ensure they receive the treatment they need.

“It feels good to get out to where they live and see how they’re doing,” she explains. “Usually, it’s when they’re in the end stage of an illness and unable to move around much.” For those unable to drive, transportation can be a problem in Idaho, as it is in many large western states. Mortimer cites the case of one woman in the advanced stages of multiple sclerosis: “It’s very hard for her to get around, so if she has a cold, I’ll go out there to make sure she’s okay and getting treatment.”

The vast landscapes and scattered towns and homesteads of Idaho are a long way from the scenes of Mortimer’s upbringing in Chicago. After receiving an undergraduate degree in philosophy and French from the University of Wisconsin, she joined the Peace Corps as a community health educator. Mortimer was posted to the Ivory Coast in West Africa during 1991-1994. “That experience was eye-opening,” she says. “Because of it, I decided I wanted to have more concrete health care skills” in order to go beyond a strictly educational focus, and to “be able to help people on more of a tangible level.”

Upon her return to the United States, Mortimer checked out a number of accelerated track programs for becoming a nurse practitioner, building upon pre-med courses from her undergraduate schooling. “I really identified with the social part of nursing, the direct care.” She decided to enroll in the master’s program in nursing at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, which she completed in 1997.

The same desire to help the underserved that had brought Mortimer into the Peace Corps guided her career search after nursing school. “I was really interested in ethnic diversity among the patients I wanted to serve.” She moved to Idaho with her husband and, in December 1997, joined the Glenns Ferry CHC, which encompasses three clinics and is located about 70 miles east of Boise.

“About 30 percent of our patients are Latino and migrant workers,” she observes. One of the clinics is near a U.S. Air Force base in Mountain Home, so many patients are drawn from there, she continues. About 60 percent of the CHC’s patients are uninsured or on Medicaid, so Glenns Ferry offers a sliding fee scale for payment. They are one of the few sliding fee clinics in that part of the State, she adds, so they draw patients from a large geographic area.

“About 30 percent of our patients are Latino and migrant workers,” she observes. One of the clinics is near a U.S. Air Force base in Mountain Home, so many patients are drawn from there, she continues. About 60 percent of the CHC’s patients are uninsured or on Medicaid, so Glenns Ferry offers a sliding fee scale for payment. They are one of the few sliding fee clinics in that part of the State, she adds, so they draw patients from a large geographic area.

“It’s been a real neat experience because you have all sorts of people you get to see every day,” Mortimer says. The health center’s service area includes Glenns Ferry, Idaho (population 1,600), and the community surrounding the air base, which encompasses another 12,000 residents. They do get some privately insured patients, particularly among the many retirees in the area and from the local farms and ranches. “From clinic to clinic there’s a very different patient population,” she finds.

Initially, Mortimer worked at Glenns Ferry’s third—and the smallest—clinic in Grandview, Idaho, that qualified for NHSC Loan Repayment. “It’s considered a ‘frontier’ clinic with a population of around a little less than 400,” she says, including many workers from a nearby livestock feedlot.

She found it took a little while to get to know local residents in the area. “The West is different that way. There’s a lot of space out here and people tend to keep to themselves. But once you give them some time, they’re really nice.”

“It’s an appealing pace of life,” Mortimer finds. “The quality of life in a smaller community can be enriching. You have access to things that matter and you don’t have to fight the traffic every day.” Those factors can be part of the appeal to health care students and clinicians for practicing in underserved regions in rural and frontier areas, she believes.

Nowadays, Mortimer rotates primarily between the Glenns Ferry and Grandview clinics, with occasional stints at Mountain Home. At the larger clinics in Glenns Ferry and Mountain Home she’ll see 20 patients on a busy day. She practices alone two days a week at the smaller site in Grandview—a physician’s assistant serves there another two days. Mortimer sees 10-15 people a day on those occasions.

From the beginning of her service at Glenns Ferry, Mortimer was given a large degree of autonomy and responsibility, in keeping with a practice in an isolated “frontier” setting such as the Grandview clinic. “When I was just out of nursing school, it was a huge challenge,” she explains, “and it still is. There are plenty of days you wish you had somebody right there to take a look at that patient’s rash, but you learn your own limits.”

She’s also glad she’s able to consult with her colleagues by phone, and often another provider rotating through the same clinic will see her patients “so you can get their input and a second opinion.”

Mortimer is actively involved in Glenns Ferry’s community education and outreach efforts. She recently organized a “walk-run” event to promote physical activity among area residents. She is also the local professional representative for the Diabetes Collaborative, sponsored by the Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC), also a part of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), NHSC’s parent agency. The purpose of the project is to eliminate disparities in the treatment and prevention of diabetes among the medically underserved. Mortimer collects outcomes data and promotes local provider “buy-in” to the goals of the BPHC initiative.

One of the lessons she’s learned has been the importance of clinicians understanding the “belief structure,” as well as the language, of the diverse ethnic populations whom they serve. In some cultures, feelings of guilt manifest themselves as physical symptoms, Mortimer says. “You need to become familiar with that sort of phenomena, which comes with time, and then look for it” when working with patients in that ethnic group. Her undergraduate degree in French also proved helpful in Mortimer’s efforts to master Spanish so she could better communicate with her Latino patients.

It is also an ongoing struggle to make sure lower income and uninsured patients are able to obtain the medications they need. “We’ve developed a patient assistance program where we streamline the application process for various programs sponsored by pharmaceutical companies,” Mortimer says. She also stresses the importance of making the patient an integral part of planning his or her treatment goals.

“You need to communicate to your patients with compassion,” she continues. “That way they understand your goals even if you can’t meet all their needs that day.”