Genome Studies Yield Insights into Childhood Leukemia

The vast majority of children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) survive the disease. But the standard treatments fail in about 20 percent of cases, and the reasons are not always understood. A new study suggests that changes to a gene called IKAROS (or IZKF1) may help explain why chemotherapy fails some patients with ALL.

Leukemia cells from a patient missing the IKAROS gene, tagged in green, with a red-colored control "probe" that shows the normal two signals per cell

Leukemia cells from a patient missing the IKAROS gene, tagged in green, with a red-colored control "probe" that shows the normal two signals per cell

An analysis of patients’ DNA and health records revealed that the IKAROS gene was mutated or deleted in two independent groups of ALL patients who had high rates of relapse. These children, the researchers concluded, may have a previously unrecognized subtype of ALL with a very poor prognosis.

If confirmed, the discovery could lead to genetic tests that identify children at high risk of relapse who may benefit from more aggressive treatments. ALL is a cancer of the blood, and IKAROS plays a role in the development of the cells that are abnormal in the disease.

“This study is an important first step toward learning how to treat ALL patients better and attaining our goal of curing all children with leukemia,” said coauthor Dr. Stephen Hunger of the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine and chair of the Children’s Oncology Group ALL Committee. “To improve the outcomes for patients who do not respond to treatment, we need to better understand how their leukemias differ from those of children who do.”

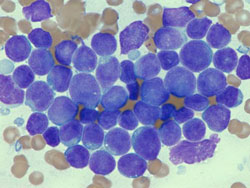

Lymphoblasts (leukemic cells in ALL) from

Lymphoblasts (leukemic cells in ALL) from

bone marrow

Results from TARGET

The IKAROS findings, which were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine last week, are the first results from the Childhood Cancer TARGET Initiative. TARGET is an NCI-supported project that brings together investigators with expertise on childhood cancers and genome analysis. The ALL study included investigators from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the Children’s Oncology Group, the University of New Mexico Cancer Research and Treatment Center, and NCI.

Using state-of-the-art technologies, the team screened ALL cells for gains and losses of DNA, profiled their gene activity, and sequenced selected genes. By integrating these results and information about each patient’s clinical course, the researchers uncovered a potential contributing factor to poor outcomes in ALL.

“We were able to accelerate the pace of discovery substantially and to identify a previously unknown group of ALL patients at risk for treatment failure,” said coauthor Dr. Malcolm Smith of NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and an NCI leader of the TARGET Initiative.

One major identifier of high-risk ALL has been the Philadelphia chromosome, and some researchers have wondered whether there were other comparable lesions associated with poor outcome. “We now know that there are, and the IKAROS deletion provides an opening for further exploring the biology of this subtype of high-risk ALL,” said Dr. Smith.

The Same Gene

The discovery builds on a report published last year showing that IKAROS is often deleted in a specific subset of ALL patients at high risk of treatment failure—those who carry the Philadelphia chromosome. IKAROS, it now appears, may be altered in children who lack the Philadelphia chromosome but who also have a high risk of relapse.

“Here we have two subtypes of leukemia that share some but not all of the same genetic changes,” said Dr. Charles Mullighan of St. Jude, the study’s first author. “Our results suggest that IKAROS has a fundamental role in the behavior of these leukemias.”

The researchers are not recommending that physicians test IKAROS in ALL patients at this time. Dr. Mullighan noted that it is not clear which types of deletions and mutations are most relevant to prognosis, and more research is needed in additional populations.

Nonetheless, knowing that IKAROS deletions occur in a second subtype of high-risk ALL “helps us to better understand the genetic heterogeneity of the disease,” said Dr. Hunger.

Counting Copies

Gains and losses of DNA—also known as copy number changes—have been reported in ALL, but it has not been known whether they influence patient outcomes. Using high-resolution microarrays and cells from 221 patients with high-risk ALL, the researchers detected copy number changes in 50 chromosome regions.

The most striking finding was the association between IKAROS changes and poor outcome. The relapse rate was approximately 75 percent for patients with IKAROS alterations, which is extremely high for ALL, noted Dr. Mullighan. This was confirmed in another group of 258 children with ALL who were treated at St. Jude.

When the team profiled gene activity in ALL tumors, they discovered patterns like those of Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL, which involves an overactive kinase protein. The similarity suggests that an overactive kinase protein may play a role in the new subtype, a theory the TARGET team is now investigating. Kinases have been the basis for successful cancer drugs such as imatinib (Gleevec).

A Gold Mine

Although changes to IKAROS may play a central role in some forms of ALL, other genes are also involved. The investigators are now cataloguing the molecular changes in the new subtype and intend to publish more results later this year.

“This is really just the beginning of what we are going to learn,” said coauthor Dr. Daniela S. Gerhard, who directs NCI’s Office of Cancer Genomics and is an NCI leader of the TARGET Initiative. The project has a wealth of biological and clinical information on these patients that can be a resource as new discoveries emerge, she explained. In the meantime, the data are available to researchers online at the TARGET Web site.

Dr. Gerhard is also a leader of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project, which employs a similar approach and has shared tools and resources with the TARGET investigators. “In terms of providing a foundation for personalized medicine, the ability to integrate genomic data and clinical information in this way has been a goldmine,” she said.

—Edward R. Winstead