Reducing Health Disparities

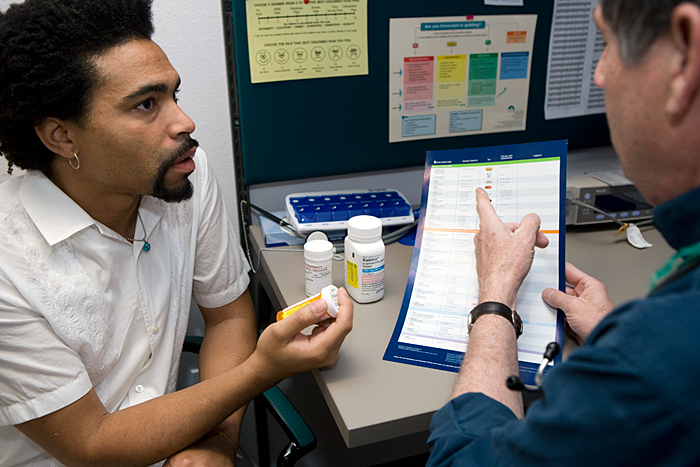

Kenneth, 35, was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in 1999, after being tested while applying for life insurance. He says he was probably infected in 1997 but didn’t seek medical attention right away.

“I wasn’t avoiding talking about the ‘elephant in the room.’ I was dealing with other things I needed to deal with, because I wasn’t sick at that time,” he says. Kenneth says he spent his retirement and savings because he was sure he wouldn’t live long enough to need them. In 2002, when he did get sick, he found himself having to navigate the often cold waters of care and case management with no resources. “Even though I was so sick, I just kept going. Every day I just told myself to keep living,” he says of those trying times.

With his health rapidly declining, Kenneth decided that it was important to get quality care from providers who listened to him and responded to his needs. He researched his options and learned about the depth of HIV/AIDS medical services provided by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s Truman Street Health Clinic. “It was a key factor in my decision to move to Albuquerque,” he says.

Because Kenneth had no health coverage, he was eligible for care through the Part C Early Intervention Services Program of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. It’s been 6 years since Kenneth enrolled in care at the Truman Street Clinic. Thanks to his care team, his determination to stay well, and a medication regimen that is working for him, his viral load is undetectable. He’s also proud to say that he is working and has employer-sponsored health insurance. “I’ve come a long way,” he says.

Results Out of Balance

Without the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, Kenneth might have become another person lost to health disparities. Uninsured, like 47 million other Americans, his lack of coverage could have led him and his health into a precipitous decline.1

Health disparities in America are directly associated with health coverage. In her testimony before Congress on April 15, 2008, Diane Rowland, Sc.D., of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, captured the situation succinctly: “Having health insurance makes a difference in whether, when, and where people get needed care. The uninsured are more likely to postpone or forego needed care and preventive services than the insured.”2

Study after study echoes Rowland’s assertions. For example, a Medscape

Medical News headline from April 11, 2007, reads, “Uninsured Have Higher

Rates of Stroke, Death.” The article cites a study in the Journal of

General Internal Medicine confirming that “individuals without insurance

are much more likely to forego routine physical examinations and are less

likely to be aware they have high blood pressure, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia.”3

According to the Institute of Medicine report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, health care disparities are defined as “differences in the quality of care received by minorities and non-minorities who have equal access to care . . . when there are no differences between these groups in their preferences and needs for treatment.”4 In addition to differences in quality of care, minorities are disproportionately affected by a host of health care conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS.5 In fact, despite continued efforts on the part of health care providers, “disparities are observed in almost all aspects of health care.”6

Tragically—and not unrelated to insurance—poor health in America is also predicted by race. The statistics are mind-boggling. African-Americans are twice as likely as their White counterparts to have a stroke; African-American men are 30 percent more likely to die from heart disease than non-Hispanic White men; Mexican-Americans, the largest share of the U.S. Hispanic population, suffer disproportionately from overweight and obesity.7,8 The list goes on to include infant mortality, many cancers, death by accident and, of course, HIV/AIDS.

A Complex Equation

The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program and many other public programs, using a comprehensive approach to care, are successfully addressing health disparities among the underinsured; racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities; young people; and other populations. These organizations understand that tackling disparities is about more than opening doors to the disenfranchised. It is about what is on the other side of those doors—something embodied in the Truman Street Health Clinic’s approach to making health care more accessible.

The Truman Street Clinic has been providing Part C–funded services since 1991 and is the sole provider of Part D services for women, infants, children, youth, and their families in the entire State of New Mexico. Within its walls, consumers find passionate providers who collaborate with patients to address the numerous problems that are associated with HIV/AIDS and that often coexist with health disparities.

In 2007, the clinic provided care, including a host of medical, case management, behavioral health, prevention, and social support services, to 881 people living with HIV/AIDS. Because it’s part of the University of New Mexico Health Medical Sciences Center, the team can initiate referrals for specialty care within the system. Eighty-six percent of the clients served are men, and 12.7 percent are women; the clinic also works with the transgendered population and has been successful in bringing young people into care. More than 50 percent of its clients are ethnic minorities, primarily Hispanics and Native Americans.

Bruce Williams, M.D., has been at Truman Street since the beginning, pioneering

the building of a community-based comprehensive care center for people living

with HIV/AIDS. Dr. Williams says, “We’ve been able to provide overall unfettered

access to care for patients living with HIV/AIDS without regard to gender,

cultural differences, or ethnicity.”

The clinic offers a safety net for people who cannot afford care. “Forty

percent of our patients are either uninsured or underinsured,” he says. With

so many active patients in the case load, Dr. Williams says that he and the

staff are starting to feel the strain of a growing demand for services but

have nevertheless been able to meet consumer needs and even expand their

programs.

For example, the Truman Street team understands the link between physical and mental health. In an effort to decrease all health disparities for which patients are at risk, the staff addresses disparities holistically. Clinic therapist Gail Jackson says that all clients get a mental health and substance abuse assessment. “Nearly 85 percent of our clients said that they had issues with one or both,” she says. “Through Part C, we have been able to fund two new positions and establish a Behavioral Health Unit to help meet those needs,” Jackson adds.

The Truman Street Clinic shares a building with its partner agency, New Mexico AIDS Services (NMAS). Because NMAS provides testing, case management, and other support services, the shared location improves client access to those services. According to Dr. Williams, Truman Street has imminent plans to open a Youth Clinic to meet the needs of a growing population of young people living with HIV/AIDS in New Mexico. “We not only have young people coming into care because of their own diagnoses, but we also have kids coming from the pediatric clinic who have been positive since birth. As they get older, they need a place to get their primary care,” he says.

Consumers Helping Each Other—and Providers, Too

In December 2007, just months after her wedding, Katrina’s life changed. She was diagnosed with HIV. “Nobody knows,” she says. “Not my family or my husband’s. The stigma and blame [are] so real. We just didn’t want to deal with it.”

At the Truman Street Clinic, Katrina has learned as much as she can about managing her treatment and the emotional stressors that go with living with HIV—from her providers and from other people who are HIV positive. Peer support among people living with a chronic illness has been shown to be a positive factor in helping them manage the physical and psychological manifestations of disease. It can also help them stay in care. Thus, peer support has a major role to play in reducing health disparities among people living with HIV/AIDS.

A shining example of this kind of support is Teddy. Now in his 50s, he has lived with AIDS for decades. He values the opportunities to share life’s lessons with young women like Katrina who seek their care at the clinic. “Older gay men have learned a lot about living with HIV and AIDS over the years. I wish there was a way that we could do more to get together with young women of color who are now dealing with the same issues,” he says. Teddy thinks that bringing the two groups together to discuss the issues would go a long way toward bridging health care disparities. “Sharing can be so important,” he says.

Consumer involvement in building care systems that mitigate health disparities goes beyond consumer-to-consumer relationships. Participating in program evaluation and adaptation to reflect changing needs is also an ideal consumer role. Without consumers’ willingness to give their time, energy, and expertise to address issues such as quality, accessibility, and cultural appropriateness, providers like the Truman Street Health Clinic would find their relevance to some consumers and their capacity to minimize health disparities compromised.

The Truman Street Clinic, like so many other Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program-funded organizations, has formalized a way of capturing consumer input by establishing a consumer advisory board. Dr. Williams and the treatment team depend on this board—whose membership reflects the clinic’s diverse client base—for valuable input on the quality and types of services they offer. In addition to working to help bridge gaps in care, clinic staff are investing in the future of quality care for people living with HIV/AIDS, says Dr. Williams. The staff nurture young physicians and other care providers by creating opportunities for them to work with patients in the clinic.

Dr. Williams says that the commitment of the clients, their work on the board, and the dedication of the staff and their partner organizations make it all come together. “We all work hard to translate what would otherwise be seen as issues into creative problem solving on behalf of our clients,” Williams says.

Notes

- DeNavas-Watt C, Proctor BD, Smith J. Income, poverty,

and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2006. Current Population Reports.

Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2007. Available at: www.census.gov/prod/2007pubs/p60-233.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2008. - Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Health care

affordability and the uninsured. Testimony of Diane Rowland, Sc.D.

for hearing on the instability of health care before the U.S. House of

Representatives Committee on Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, April

15, 2008. Available at: www.kff.org/uninsured/upload/7767.pdf.

Accessed July 8, 2008.

Accessed July 8, 2008. - Uninsured

have higher rates of stroke, death. Medscape Medical News, April 11, 2007.

Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/555051.

Accessed May 8, 2008.

Accessed May 8, 2008. - Smedley

BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR (Eds.). Unequal treatment: confronting racial

and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academic

Press, 2002. Available at: www.iom.edu/CMS/3740/4475.aspx.

Accessed

June 3, 2008.

Accessed

June 3, 2008. - Office of Minority Health (OMH). Data by health topic. n.d. Available at: www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=9. Accessed June 3, 2008.

- Key themes and highlights from the national healthcare disparities report. January 2007. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr06/highlights/nhdr06high.htm. Accessed June 3, 2008.

- OMH. Stroke data/statistics. Available at: www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=10. Accessed May 8, 2008.

- OMH. Heart disease data/statistics. Available

at:

www.omhrc.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=6.

Accessed May 8, 2008.