|

|

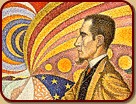

Mark Leithauser is Chief of Design at the National

Gallery of Art. Beginning with an internship at the NGA nearly twenty-five years ago, he has participated in the creative

development of more than four hundred National Gallery exhibitions. He cocurated the National Gallery's version of the Art

Nouveau exhibition with the NGA's Chief of Exhibitions, D. Dodge Thompson.

Mark Leithauser is Chief of Design at the National

Gallery of Art. Beginning with an internship at the NGA nearly twenty-five years ago, he has participated in the creative

development of more than four hundred National Gallery exhibitions. He cocurated the National Gallery's version of the Art

Nouveau exhibition with the NGA's Chief of Exhibitions, D. Dodge Thompson.

We talked with Mark about his department's critical role in the Gallery's planning and presentation of exhibitions.

|

How do you begin assembling the many

pieces that will make up an exhibition?

How do you begin assembling the many

pieces that will make up an exhibition? |

We take color photocopies of all of the objects and stylistic

examples proposed for a show and pin them up on the wall. From these we try to make sense of the exhibition, try to put the

images into groups that make sense. In the case of Art Nouveau, the works are categorized under eight cities in which the style

flourished. Art Nouveau, despite its reliance on the natural world as a stylistic influence, was an urban phenomenon.

We take color photocopies of all of the objects and stylistic

examples proposed for a show and pin them up on the wall. From these we try to make sense of the exhibition, try to put the

images into groups that make sense. In the case of Art Nouveau, the works are categorized under eight cities in which the style

flourished. Art Nouveau, despite its reliance on the natural world as a stylistic influence, was an urban phenomenon.

Once we organize the objects in meaningful groups, we start actually blocking out spaces and structuring our art historical

arguments, just as you would with any good piece of music, any play or book. |

So creating an exhibition is something like storytelling?

So creating an exhibition is something like storytelling? |

An exhibition should have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

It ought to tell a story while putting forward an art historical point of view. The Art Nouveau story is extremely complicated

because it was such a broad movement. It was occurring on different continents and with different interpretations in different

countries.

An exhibition should have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

It ought to tell a story while putting forward an art historical point of view. The Art Nouveau story is extremely complicated

because it was such a broad movement. It was occurring on different continents and with different interpretations in different

countries.

We want people who have no idea what Art Nouveau was to come in and get something out of their visit. We also want to make the

presentation a rich and rewarding experience for scholars in the field. A good exhibition should work on various levels, and I

think this one does. |

Once your story line is in order, what's next?

Once your story line is in order, what's next? |

Then we begin rough drawings. A room can start literally with

a thumbnail sketch. Sketch, sketch, sketch, sketch--thousands of sketches. I don't know if you've seen I.M. Pei's initial idea

for the East Building, but it was sketched on a napkin.

Then we begin rough drawings. A room can start literally with

a thumbnail sketch. Sketch, sketch, sketch, sketch--thousands of sketches. I don't know if you've seen I.M. Pei's initial idea

for the East Building, but it was sketched on a napkin.

The loose initial drawings are taken from the designer and translated by designer architects into meticulous architectural

drawings from which the carpenters, electricians, and estimators can build an exhibition space.

The loose initial drawings are taken from the designer and translated by designer architects into meticulous architectural

drawings from which the carpenters, electricians, and estimators can build an exhibition space.

Then we begin making maquettes, or scale models, of all the pieces in the show. These aren't toys, fun as they might seem.

They are exact architectural scale models, which tell us, three-dimensionally, how much space a case or object is going to occupy.

The maquette is the initial tool by which we explore the potential position of objects in the exhibition space. If this process is

not well executed, you could make some real mistakes--such as not leaving enough space around a piece of furniture for people to

move safely and comfortably past it. |

So you're thinking about visitors even at this early phase of design?

So you're thinking about visitors even at this early phase of design? |

We have to keep visitors in mind in all exhibitions and at all times.

For example, we know that viewers will crowd around something like jewelry. In The Treasure Houses of Britain, a special exhibition

in the 1980s, there was a case of four or five tiaras, including one of Princess Diana's. That case was incredibly popular! People want to

have a one-on-one relationship with a Vermeer painting, or King Tut's bejeweled headdress, whether we allow sufficient room

or not.

We have to keep visitors in mind in all exhibitions and at all times.

For example, we know that viewers will crowd around something like jewelry. In The Treasure Houses of Britain, a special exhibition

in the 1980s, there was a case of four or five tiaras, including one of Princess Diana's. That case was incredibly popular! People want to

have a one-on-one relationship with a Vermeer painting, or King Tut's bejeweled headdress, whether we allow sufficient room

or not.

For the Vermeer show we hung the paintings so sparsely that it seemed almost ludicrous...the works looked like little postage stamps

on those big walls! But when the NGA's doors opened at ten o'clock and a thousand people came in every twenty minutes, we were

glad we had provided plenty of space.

We can mitigate the problem of terrible crowding, but we don't want to discourage someone from spending one-on-one time with a

revered object. In the Art Nouveau exhibition, the Lalique dragonfly brooch will attract admiring crowds...so we're installing it

in a big room.

We can mitigate the problem of terrible crowding, but we don't want to discourage someone from spending one-on-one time with a

revered object. In the Art Nouveau exhibition, the Lalique dragonfly brooch will attract admiring crowds...so we're installing it

in a big room.

Another potential bottleneck is the exit from the introductory film. People will pour into the auditorium in a steady stream,

but while they are watching the film there will be a build-up of fifty to sixty people, who will all come out at once and pulse

into the exhibition in a throng. They will eventually spread throughout the show, due to different levels of interest, but that

initial pulsing is a real concern. |

How does Art Nouveau compare in size to other NGA exhibitions?

How does Art Nouveau compare in size to other NGA exhibitions? |

Some shows have filled as little as 1,200 square feet, and others

as much as 36,000, so they vary tremendously. This is one of our larger exhibitions in terms of square footage and will probably

cover about 18,000 square feet of gallery space.

Some shows have filled as little as 1,200 square feet, and others

as much as 36,000, so they vary tremendously. This is one of our larger exhibitions in terms of square footage and will probably

cover about 18,000 square feet of gallery space. |

There must be numerous conservation issues in a show of this scale.

There must be numerous conservation issues in a show of this scale. |

There are indeed--especially in an exhibition like this, in

which a great variety of materials are being brought together. We are displaying a Japanese kimono, which is delicate and

highly sensitive to light and must be hung a certain way. Alongside we have jade, carved wood, wood inlay, ivory, stone,

oil on canvas, works on paper--and that's just in one room, off the top of my head!

There are indeed--especially in an exhibition like this, in

which a great variety of materials are being brought together. We are displaying a Japanese kimono, which is delicate and

highly sensitive to light and must be hung a certain way. Alongside we have jade, carved wood, wood inlay, ivory, stone,

oil on canvas, works on paper--and that's just in one room, off the top of my head!

Often these objects have conflicting requirements. The ivory has to stay relatively moist--it can't be allowed to dry out--so

we'll create a microclimate in the case for that object. We build special display cases that won't leak humidity, and

weeks before such a case is to be sealed, our conservators will humidify it. Gauges in the case are read by a computer that will

stabilize the case at the temperature and relative humidity stipulated in the loan agreement for that particular object. The

case right next to it might have a significantly different microclimate. There might be a ten percent difference in humidity or more.

Often these objects have conflicting requirements. The ivory has to stay relatively moist--it can't be allowed to dry out--so

we'll create a microclimate in the case for that object. We build special display cases that won't leak humidity, and

weeks before such a case is to be sealed, our conservators will humidify it. Gauges in the case are read by a computer that will

stabilize the case at the temperature and relative humidity stipulated in the loan agreement for that particular object. The

case right next to it might have a significantly different microclimate. There might be a ten percent difference in humidity or more.

The kimono can be exposed to only five foot-candles of light, which requires very low illumination. It might be displayed next

to a bronze sculpture, which has no light restrictions. The challenge of our lighting designer, Gordon Anson, is to make sure

that the balance makes sense, that one object isn't glaring at you while the other seems to be in the gloom. |

Do you work with the curators for an exhibition when

deciding where to position the works of art?

Do you work with the curators for an exhibition when

deciding where to position the works of art? |

We always work with the curators. The best way to install

any exhibition is for the experts in the field to come in, and we all make decisions together. For Art Nouveau, we worked

very closely with Paul Greenhalgh and Ghislaine Wood, who are experts in decorative arts of this period.

We started by talking with them and defining groups of objects with their participation. We have all moved back and forth with our ideas

and talked with other experts as well to come up with the final configuration. So it's a big team effort...a lot of gifted

people giving a lot of good advice.

We always work with the curators. The best way to install

any exhibition is for the experts in the field to come in, and we all make decisions together. For Art Nouveau, we worked

very closely with Paul Greenhalgh and Ghislaine Wood, who are experts in decorative arts of this period.

We started by talking with them and defining groups of objects with their participation. We have all moved back and forth with our ideas

and talked with other experts as well to come up with the final configuration. So it's a big team effort...a lot of gifted

people giving a lot of good advice. |

Walk us through the structure of the exhibition...how

does the story of Art Nouveau begin?

Walk us through the structure of the exhibition...how

does the story of Art Nouveau begin? |

We start our show differently than the V&A did, displaying a

variety of objects that are all documented to have been in the Paris World's Fair in 1900. These works are intended to introduce

viewers to the Art Nouveau style. There are radically different pieces in this room: the floral style and the geometric style

are represented, as are French works, an American work by Louis Comfort Tiffany, as well as Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, German,

Austrian pieces--a great array of objects!

We start our show differently than the V&A did, displaying a

variety of objects that are all documented to have been in the Paris World's Fair in 1900. These works are intended to introduce

viewers to the Art Nouveau style. There are radically different pieces in this room: the floral style and the geometric style

are represented, as are French works, an American work by Louis Comfort Tiffany, as well as Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, German,

Austrian pieces--a great array of objects!

There is also an audiovisual presentation at the beginning of the exhibition, and it's here for a number of reasons. We think

that this exhibition is so complicated that an introductory film will provide a valuable orientation. Its location also gives

visitors the option of coming back to see the film at the end of the exhibition. |

So, once visitors have been briefed on just what Art Nouveau

is...what will they see next?

So, once visitors have been briefed on just what Art Nouveau

is...what will they see next? |

What follows are several small sections that demonstrate

the sources of Art Nouveau. The Celtic and Viking revivals and their influence on designers like American architect Louis

Sullivan are represented here, followed by examples of rococo styling, Chinese furniture,

Japanese prints,

What follows are several small sections that demonstrate

the sources of Art Nouveau. The Celtic and Viking revivals and their influence on designers like American architect Louis

Sullivan are represented here, followed by examples of rococo styling, Chinese furniture,

Japanese prints,

Near Eastern glassware that Tiffany copied, aestheticism with reference to James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Aubrey

Beardsley, symbolist paintings by Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, Paul Signac, Odilon Redon, and others. Finally, the "cult of nature" section

demonstrates the influence of natural forms on Art Nouveau design. We'll display gourds, orchids as torchéres, and other organic forms. Near Eastern glassware that Tiffany copied, aestheticism with reference to James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Aubrey

Beardsley, symbolist paintings by Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, Paul Signac, Odilon Redon, and others. Finally, the "cult of nature" section

demonstrates the influence of natural forms on Art Nouveau design. We'll display gourds, orchids as torchéres, and other organic forms.

After that we focus on prime examples of objects--of all shapes and sizes and media--from each of eight cities, including Paris,

Brussels, Glasgow, Vienna, Munich, Turin, New York, and Chicago. We have borrowed works of art to create the best

representation possible for each city. |

Some of the great Art Nouveau artists like Antoní

Gaudí and Victor Horta were primarily architects. How do you represent them in the exhibition?

Some of the great Art Nouveau artists like Antoní

Gaudí and Victor Horta were primarily architects. How do you represent them in the exhibition? |

Whenever possible and when objects are moveable, we try to

borrow the most essential works we can. Fortunately, Art Nouveau architects designed not only the buildings but the rooms,

the walls, the pictures, the furniture, the silverware, the table--the whole experience. We include Gaudí in the rococo section,

with an intriguing comparison between one of his clocks and a clock from about 1780. They are amazingly similar and different

at the same time. But Gaudí is really an architect, and it is not possible to bring his buildings to Washington.

Whenever possible and when objects are moveable, we try to

borrow the most essential works we can. Fortunately, Art Nouveau architects designed not only the buildings but the rooms,

the walls, the pictures, the furniture, the silverware, the table--the whole experience. We include Gaudí in the rococo section,

with an intriguing comparison between one of his clocks and a clock from about 1780. They are amazingly similar and different

at the same time. But Gaudí is really an architect, and it is not possible to bring his buildings to Washington.

There will also be color photomurals representing several astounding Art Nouveau buildings, such as the Horta house, which is

probably the best-known Art Nouveau image there is.

There will also be color photomurals representing several astounding Art Nouveau buildings, such as the Horta house, which is

probably the best-known Art Nouveau image there is.

We're lucky to have two actual, complete Art Nouveau rooms installed for this exhibition. This is a stunning treat. And they're

radically different--the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Ladies' Luncheon Room being so geometric, and then, just two rooms away, the wonderfully

curvilinear double parlor from Turin designed by Agostino Lauro. |

You've echoed the curvilinear, organic Art Nouveau style

in the design for the room that houses the Métropolitain entrance. What was the impetus to create such a free-form space?

You've echoed the curvilinear, organic Art Nouveau style

in the design for the room that houses the Métropolitain entrance. What was the impetus to create such a free-form space? |

We try to evoke elements of the style of objects installed in

a room to put the works of art into a congenial setting. I think there are effective examples of that effort in this show.

We try to evoke elements of the style of objects installed in

a room to put the works of art into a congenial setting. I think there are effective examples of that effort in this show.

The organic room you're talking about, the Metro station room, should feel like the proverbial "ship in the basement" when

visitors enter it. They will have gone through three or four strict museum rooms in succession--the "cult of nature," symbolism,

the English room--then all of a sudden they reach this room with curved walls and no corners. It should really be

worth climbing the steps for!

The organic room you're talking about, the Metro station room, should feel like the proverbial "ship in the basement" when

visitors enter it. They will have gone through three or four strict museum rooms in succession--the "cult of nature," symbolism,

the English room--then all of a sudden they reach this room with curved walls and no corners. It should really be

worth climbing the steps for!

We're always aware of the effort it takes to climb the spiral staircase to the upper level in the East Building. When visitors

get to the top of those stairs, there's got to be a payoff. The should think to themselves, "How in the world did the museum

get that up here?"

I think if Hector Guimard had been given a budget and a pencil to contribute his thoughts, he would have invented this kind

of room...a room with no corners. |

You must be really challenging your staff to create

such complex spaces.

You must be really challenging your staff to create

such complex spaces. |

I debated on which day to have Randy Payne, our head of the

exhibits shop, come up and see the designs. I thought, "Not a Monday." So I waited until Friday when he was in a really good

mood, and we sat down. He said, "Sure, I'd love the challenge!" By Tuesday he was in a crabby mood again. But he and his

team are so talented, and they are devoted to their work for the NGA. I'm very proud of them.

I debated on which day to have Randy Payne, our head of the

exhibits shop, come up and see the designs. I thought, "Not a Monday." So I waited until Friday when he was in a really good

mood, and we sat down. He said, "Sure, I'd love the challenge!" By Tuesday he was in a crabby mood again. But he and his

team are so talented, and they are devoted to their work for the NGA. I'm very proud of them.

Just in the design office we have about forty full-time craftspeople: graphic designers, state-of-the-art lighting experts,

and armature makers. We have architects who are accustomed not

only to building rooms but to constructing microclimates and cases that are easily accessible and well lit without creating

problems like heat build-up or desiccation. We have a very serious budget analyst, a maquette (model) maker,

great carpenters, cabinetmakers, painters, silkscreeners...the list goes on and on.

Just in the design office we have about forty full-time craftspeople: graphic designers, state-of-the-art lighting experts,

and armature makers. We have architects who are accustomed not

only to building rooms but to constructing microclimates and cases that are easily accessible and well lit without creating

problems like heat build-up or desiccation. We have a very serious budget analyst, a maquette (model) maker,

great carpenters, cabinetmakers, painters, silkscreeners...the list goes on and on.

I can modestly say the staff here is the best in the world. It was set up that way by our former director, J. Carter Brown,

and it's been carefully maintained by our present director, Earl A. Powell III. Carter Brown said long ago that if we were

going to ask for the world's greatest art to come here, we had to put it into a context worthy of it. He was absolutely right.

We do very well in borrowing works of art because lenders know their objects are going to be beautifully installed and properly

cared for from the minute they leave the lenders' hands to the minute they return.

|

|

|