Looking to Refine HER2-targeted Therapy

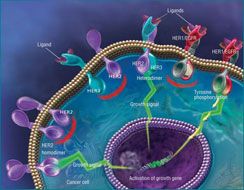

HER proteins are part of an intracellular signaling pathway (depicted above) that is critical to many cellular functions. HER2 overexpression can lead to unchecked growth and, eventually, cancer. Click to enlarge.

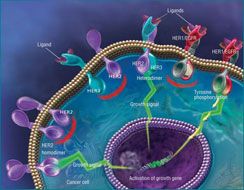

HER proteins are part of an intracellular signaling pathway (depicted above) that is critical to many cellular functions. HER2 overexpression can lead to unchecked growth and, eventually, cancer. Click to enlarge.

When is a patient a candidate for a targeted therapy? That’s a question some breast cancer researchers are attempting to answer in the wake of results from several studies presented in 2007 that suggested the definition of HER2-positive—that is, women whose breast tumors produce an excess of the HER2 protein—may be too strict. These retrospective studies showed that even women who were HER2-negative benefited from the HER2-targeted agent trastuzumab (Herceptin).

A monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab has been one of the most frequently cited success stories of the early era of molecularly targeted therapies. Its use improves progression-free and overall survival in women with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, and current data suggest it has a dramatic impact on the likelihood of cure for women with early stage HER2-positive disease.

Not all of the studies that continue trickling into the literature support the findings from those 2007 studies, but there is enough evidence, argued Dr. Peter Kaufman, professor of medicine at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, to suggest “that we may need to rethink conventional dogma.”

Hints of Something, but What?

Breast cancer experts agree that the recent studies are hypothesis-generating and should not dictate current clinical practice. After all, choosing breast cancer patients’ treatment based on HER2 status has been a successful paradigm, said Dr. Laura Esserman, who directs the breast cancer program at the Helen Diller Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, San Francisco.

“In general, targeting HER2 has proven to be the right thing to do,” she said. “I think it’s pretty clear that we’ve done a good job. It hasn’t been perfect, though. There’s room for improvement.”

The Measure of a Target

IHC (immunohistochemistry) and FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) are the two testing methods recommended in the ASCO/CAP HER2-testing guidelines, which detail how the tests should be performed and what constitutes HER2-positive, -negative, and equivocal or borderline results. The IHC assay measures the amount of HER2 protein expressed in cancer cells, while the FISH assay measures either the total number of copies of the HER2 gene in a tumor cell or the ratio of HER2 genes to chromosome 17 copies.

| Result |

IHC |

FISH (two approaches) |

| Positive |

3+ |

<6 HER2 copies per cell or HER2:ch 17 ratio of 2.2 to 1 |

| Negative |

0+, 1+ |

<4 HER2 copies per cell or HER2:ch 17 ratio <1.8 to 1 |

| Equivocal |

2+ |

4 – 5 HER2 copies or 1.8 – 2.2 HER2:ch 17 ratio |

For example, researchers would like to find ways to improve the response rate to trastuzumab, which hovers between 25 and 30 percent. There are also misgivings about the accuracy of HER2 testing, concerns that were significant enough to prompt the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) to develop clinical guidelines for HER2 testing.

“This is a tumor marker that’s being used as the sole determinant of therapy selection,” explained the guidelines panel co-chair, Dr. Antonio C. Wolff of the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center. “That’s why it’s important that pathologists do their best to adhere to the guidelines and clinicians ask questions about the quality of testing.”

It’s also critical to continue clinical research on the use of HER2-targeted therapies like trastuzumab and lapatinib (Tykerb), Dr. Wolff added. “You need to be confident that you’re talking about true HER2-positive or -negative tumors. Then you can start looking at clinical outcomes,” he said.

The response rate and accuracy issues overlap with the questions about the definition of HER2-positive, which is most commonly determined with two tests, IHC and FISH. (See sidebar.)

The IHC and FISH cutoffs that correspond with response to trastuzumab were established based on clinical trials involving women with metastatic breast cancer, explained Dr. Tracy Lively, associate chief of the Diagnostics Evaluation Branch in NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis. The recent data, she added, suggest that perhaps those cutoffs may need to be modified for women being treated for early stage disease.

At the 2007 ASCO annual meeting, Dr. Soonmyung Paik, director of the Division of Pathology for the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) in Pittsburgh, first suggested the same thing. Dr. Paik and his colleagues had conducted an unplanned, retrospective analysis of available tumor samples from the B-31 trial, which compared adjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab to chemotherapy alone in women with HER2-positive, early stage breast cancer.

After retesting the tumor blocks, they found that 10 percent were truly HER2-negative (meaning the women shouldn’t have been enrolled in the trial). Nevertheless, there was a statistically significant trend toward improved outcomes in HER2-negative patients treated with trastuzumab. In fact, every HER2-negative patient subset saw some benefit, although not all reached statistical significance.

The findings were consistent with data from two other studies presented at the meeting, including another unplanned, retrospective analysis led by Dr. Kaufman of tumor samples from women with metastatic breast cancer in the CALGB 9840 trial. Some women in the trial whose tumors were HER2-negative according to FISH but who also had polysomy of chromosome 17—extra copies of chromosome 17, where the HER2 gene resides—had improved response rates to treatment with trastuzumab and chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone.

“That raised a fair number of eyebrows,” Dr. Kaufman said. “But, again, these findings are preliminary. It could just be a fluke due to the small sample size and retrospective analysis.”

Data on this topic continue to emerge, including a recent study led by Dr. Michael Press from the Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Southern California, which found no benefit from lapatinib in HER2-negative women.

Where to Go from Here

A large clinical trial is needed to determine whether some women, whose tumors reside somewhere in the molecular middle between HER2-negative and -positive, could benefit from HER2-targeted therapy, said Dr. Lively.

Such a study could be on the horizon. A validation study to confirm the results from Dr. Paik’s earlier study “is moving forward quickly,” explained NSABP Director of Medical Affairs Dr. Charles Geyer. If the results are positive, he continued, NSABP plans to conduct a clinical trial that would look at whether women with breast tumors that fall into a “HER2-low” category may benefit clinically from HER2-targeted therapy.

In the meantime, Dr. Esserman said, although the available data have raised some tough questions, she sees a positive side.

“It’s not necessarily that these assays are wrong,” she said. “Maybe there’s just a better way to measure.”

Dr. Esserman, for instance, is a co-principal investigator of a clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for women with early stage breast cancer called I-SPY. The trial is using molecular analyses of serial biopsies and serial MRI scans to identify markers of response to treatment. One area showing promise, she noted, is the correlation of the levels of phosphorylated HER2 protein (the addition of phosphate groups to the protein, which regulates its activity) with other measures of HER2 expression and response to trastuzumab.

Much further along the clinical spectrum is an assay developed by San Francisco-based Monogram Biosciences called HERmark. According to the company, the assay provides a more exact measurement of HER2 levels, as well as the extent of the complexes formed by HER2 proteins on the surface of cancer cells (called dimers). Smaller studies presented at national meetings have suggested the assay can more accurately predict which women, including those who are HER2-positive, will respond to trastuzumab.

“Without the controversy,” Dr. Esserman said, “I don’t think there would be as much motivation to develop new and better assays.”

—Carmen Phillips