|

|

|

|

September 2007 Broaden Understanding Boldly Intervene Build Relationships Bridge Barriers to Care |

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

|

| DID YOU KNOW? |

|

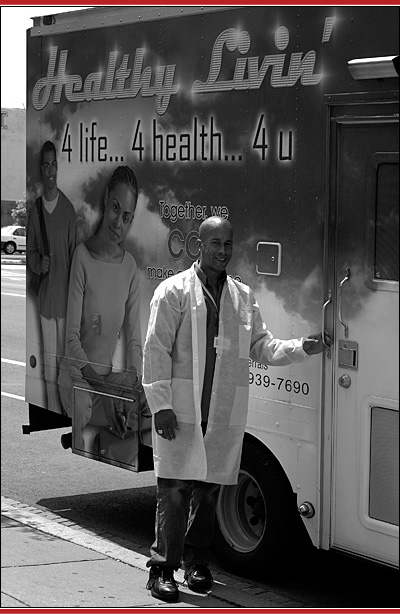

After the van is parked, WWC program manager Christopher Hubbard begins to assemble HIV testing kits. Almost immediately, there is a knock at the side door of the van. When Hubbard opens the door, a young black man stands immobile for a moment. Then, first looking over his shoulder and then back at Hubbard, he asks, “Are you open yet?”

“Yes, we’re just finishing setting up. Did you want to get tested?” asks Hubbard.

“No, I tested positive last year,” the man answers.

At this, Hubbard steps out of the van to talk to him. Soon, the man confides that he is not in care because he is afraid of being seen going into what he perceives to be “the HIV clinic” in his neighborhood. Hubbard explains that WWC is a primary care clinic, not an HIV clinic, but the man is unmoved. It is only when Hubbard tells the man about the Max Robinson Center, a WWC site that is far away from his neighborhood—one where he may not be recognized—that a sense of calm seems to wash over him. His eyes widen, and he accepts the information Hubbard hands to him. He glances down at the information and then, with a single nod of acknowledgement, turns and walks away.

The fear of being recognized is just one of many barriers that keep people out of care or cause them to drop out after they have been enrolled. Historically, providers like WWC have sought to help people transcend those barriers, become enrolled in care, and remain there over time. They have done so by providing any of a number of services that are often referred to under the umbrella of “outreach.”

Broaden Understanding

Outreach is a nonspecific term that sometimes causes confusion—more for what it doesn’t communicate than what it does. The literal meaning of outreach is “to reach out,” but in practice, the term requires clarification.3 Outreach for what purpose? To educate or prevent? To inform? To find? Moreover, to whom is the outreach targeted? A large, heterogeneous group? To a group defined by common characteristics? If so, what are those characteristics?

These and many other questions have surrounded outreach for much of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States. Today, many questions have been answered. With regard to the Ryan White Programs, the objectives of outreach services are clearer than ever before. Those objectives are as follows:

- To engage and enroll PLWHA in care who have never been or who have dropped out, and

- To retain PLWHA in care over time.

Neither objective is as simple as it may seem.

The life circumstances of many PLWHA and the social and health care environment in which we live today make providing support for engagement and retention an undertaking with many moving parts. Ultimately, providers must address barriers separating people from appropriate care, and doing so requires a level of provider engagement significantly greater than that encountered in the typical outpatient medical care environment. To deliver such services, providers must start by identifying and connecting with those who need help.

Ideally, clients would progress from not knowing they are [HIV] infected to becoming fully engaged [in care]. The reality is quite different. Any given client may cycle through different stages at given time periods.1

The question of whether a person has ever been engaged in care or is receiving care may seem elementary, but it cannot be answered in absolutes. The reality is that all PLWHA are at different points along what can be referred to as the “engagement-in-care continuum” (see figure below).

At one end of the spectrum are people who are unaware of their serostatus; at the other end are those receiving appropriate care. But many other people are at various points between the two extremes: For example, some PLWHA may have been engaged in medical care but never enrolled in HIV care; others have been in care but later lost to follow-up. Wherever they are on the engagement-in-care continuum, the position of many PLWHA is not static.

Just because a PLWHA does not need engagement or retention support today does not mean that he or she will not tomorrow. People drop out of care and need to be “reengaged.” People retained successfully for a period of time may suddenly become at risk for being lost to follow-up. The providers who are most successful—those who make engagement and retention work—are those who remain alert to the ever-changing needs of their clients. They also make risk assessment more than a one-time event.

Complicating matters further, the people who are not receiving appropriate care or who are at risk for not receiving it are not a homogenous group. They come from diverse subpopulations and often struggle with barriers to care including lack of stable housing, substance abuse, low levels of education and health literacy, and poverty, all of which are commonly associated with HIV/AIDS in the United States.

Those factors, widely explored in the literature and in practice,

often make engagement and retention of PLWHA an intensive, time-consuming,

and ongoing process.

|

| Reprinted from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) HIV/AIDS Bureau (HAB). Outreach: engaging people in HIV care. August 2006. Available at: ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov/hab/HIVoutreach.pdf. pp. 2-3. |

Boldly Intervene

Because PLWHA needing engagement or retention services are

so diverse, many programs choose to target demographic groups—such

as women, adolescents, or racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately

affected by HIV/AIDS. Others target PLWHA at a specific point along the engagement-in-care

continuum, such as PLWHA who are lost to follow-up or, like the Brothers

Saving Brothers project, those who are unaware of their serostatus.

The Brothers Saving Brothers project is run by the Horizons Project, a collaboration between Wayne State University and Detroit Medical Center. Horizons is one of nine grantees funded through the Ryan White Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) Young Men of Color Who Have Sex With Men Initiative.

Through the Brothers Saving Brothers project, Horizons is implementing and evaluating a model that uses Internet chat rooms to reach young men who have sex with men (MSM). The initiative reflects “associations between Internet sex-seeking and high-risk sexual behavior [and] evidence of sexually transmitted infections (STI) acquired from Internet-identified sex partners.”4,5 It also reflects that the phrase “meeting people where they are” applies to engagement and retention in a literal sense. Since inception, the Brothers Saving Brothers interventions have provided HIV testing to 36 men, 4 of whom were HIV positive.

WWC’s outreach project intervenes at various points in the engagement-in-care continuum. It reaches PLWHA who are in care but are at risk for being lost to care as well as those who may not be in care at all.

Like many providers, WWC uses funds from diverse sources to support specific services. For example, its outreach van is supported through funding from the District of Columbia’s HIV/AIDS Administration, a division of the Washington, DC, Department of Health. It provided retention services to those at risk of falling out of care with the support of the SPNS Outreach Initiative, which was active from 2001 to 2006.

As part of its project, WWC created a new position, retention care coordinator (RCC). To identify patients at risk for falling out of care and in need of intervention, an algorithm was created in partnership with Georgetown University School of Nursing and Health Studies. The algorithm took into account factors such as race and ethnicity, employment status, and drug use (or number of years clean from drug use).6 Patients with a 75 percent or greater probability of falling out of care were recruited for the program.7

“We had a no-show rate nearing 40 percent, and that gave us cause for alarm,” says Debra Dekker, WWC’s senior program evaluator. “We knew we needed to do something.”

In response, Dekker says, “Patients received reminders the day before the appointment. We provided transportation assistance in the form of bus tokens or Metro fare cards. Since child care was a barrier, we would reimburse them for a babysitter of their choosing.” RCCs also accompanied patients to medical visits, provided treatment and medication adherence support, and helped patients navigate services either at the clinic or at other health care institutions.7

When WWC began its retention project, the no-show rate was 36.5 percent at its Elizabeth Taylor Center and 34.2 percent at its Max Robinson Center. After 12 months, the no-show rates were 29.7 and 26.4 percent, respectively—still high, yet reflecting a decrease of almost 7 percentage points at one site and almost 6 at the other.7

The Ryan White Programs offer numerous examples of organizations like Horizons and WWC that provide effective engagement and retention services. Whether programs are casting a wide net or targeting small subpopulations, the results show that engagement and retention services can yield results. They also show that the results don’t come easy—and that most organizations shouldn’t go it alone.

Build Relationships

We found our patients via the OB/GYN clinic at Jackson Memorial. Most of the women went to the OB/GYN clinic there because they were pregnant. They were eligible for HIV care but weren’t accessing it.

Tanya

Quill, Project Director

Caring Connections, Miami, FL

Organizations that find PLWHA need a way to engage and link their clients to HIV care. Organizations that engage PLWHA need a way of keeping them there.

One method is to build relationships with “key points of entry” into the medical system, as described in the Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act Amendments of 2000. Such organizations include “emergency rooms, substance abuse treatment programs, detoxification centers, adult and juvenile detention facilities, sexually transmitted disease clinics, HIV counseling and testing sites, mental health programs, and homeless shelters.”8 Relationships with organizations like those—and with others, such as primary care providers who are ill-equipped or unwilling to care for PLWHA—are pivotal in both engaging and retaining people in care.

The CareLink Experience

In 2001, Cascade AIDS Project in Portland, Oregon, received Ryan White Part A (Title I) funds to establish CareLink. Through funds from the SPNS Outreach Initiative, the program was able to expand to provide more intensive services. (The program has continued in a more limited capacity since the SPNS grant expired.) The goal of the program is to reach PLWHA not in care or at risk for falling out of care.

In Portland, case managers are located within medical facilities. Clients entering care do not receive case management until they chose a medical provider—a daunting task for PLWHA unfamiliar with the health care system. In addition, case managers did not have the capacity to find patients lost to care and reengage them in the process.7 CareLink filled this gap in the care continuum by using advocacy and outreach workers to support individual patients and engage them in care. In total, 129 clients were served in 2006 through the program: 108 clients out of care and 21 clients at risk for leaving care. After CareLink’s intervention, 106 clients (82 percent of those contacted) were engaged in care.

“Connecting clients to a retention care counselor or a case manager is a critical component to keeping people in care,” says Donna Standing Rock, CareLink advocacy worker. “These individuals are willing to go out of their way and help. In an environment that is increasingly about helping oneself, that is remarkable.”

As most providers have discovered, however,

resolving engagement and retention issues isn’t solely a matter of

what is going on inside the organization. Instead, relationships with other

providers are key to success.

The Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) Outreach Initiative grantees (2001-2006) evaluated model interventions including motivational interviewing, staff training, use of peers, health system navigational assistance, use of alternative settings for care, and harm reduction. Lessons include the following:

|

| Source: From Center for Outreach Research and Evaluation, Health & Disability Working Group (CORE/HDWG), Boston University School of Public Health. 2006. Making the connection: promoting engagement and retention in HIV medical care among hard-to-reach populations. Available at: www.bu.edu/hdwg/pdf/projects/LessonLearnedFinal.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2007. pp. 4-5. |

“Initially,” says Alison Frye, manager of the Client Outreach and Assessment Department at Cascade AIDS Project, “we took to the streets looking for PLWHA. Soon, we realized that we needed a better way of reaching them. For us, this meant building partnerships,” such as with the county corrections medical unit. “Many of our clients have been in jail or have a criminal background,” says Frye, “so linking with the corrections system was an obvious step for us.”

The experience

of CareLink and the Portland community illuminates what Frye9 refers to as

keys for building the partnerships necessary for linking PLWHA not in care

to the HIV/AIDS service system:

1. Identify partners.

Major

partners were identified as the county corrections medical unit, the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded HIV community testing site,

the Part C (Title III) HIV primary care clinic along with the hospital-based

HIV primary clinic, and the case management program. Other partners included

landlords of housing facilities where CareLink staff try to place clients.

2. Institute clear roles, responsibility, and accountability.

Because CareLink’s services had the potential to overlap with partnering agencies,

communication about responsibilities at inception was crucial, as was buy-in.

To avoid any duplication, CareLink created memoranda of understanding to

specify “CareLink’s

role and relationship with each [organization], including how referrals were

to be made.”10

3. Create and sustain relationships.

Frye attends

monthly meetings with each case management team to discuss clients. She

also sits on the local Part A (Title I) Planning Council. Periodically

reconnecting with partner organizations is important because of high staff

turnover. Reconnecting also helps identify and resolve communications issues.

4. Link outreach and case management.

Cascade AIDS Project and the case

management program created a joint intake process. According to program

literature, that process “included a joint release of information between the two

agencies. This meant that clients who signed the joint release form and were

lost to follow-up in case management services could be referred to CareLink

for outreach, and clients who first came in contact with CareLink could receive

an intake for case management services.”11

Bridge Barriers to Care

Retention [is] ultimately about building relationships with clients.

Debra

Dekker

A fundamental objective of engagement and retention services is to ensure access to HIV/AIDS medical care. But primary medical care is only part of the engagement and retention equation. Why? Because the path to primary care is obstructed. Clearing it requires that the needs of the whole person be addressed—something that effective providers have been doing for a long time. They must continue to do so, given that the need for social and essential support services among PLWHA remains high.

George Castrataro is supervising attorney at the Consumer Law Unit and HIV/AIDS Law Project at Legal Aid Service of Broward County, Inc. in Florida—a county with the unenviable distinction of having the Nation’s fastest growing AIDS rate.12 The organization receives Ryan White Program Part A (Title I) funding through the Fort Lauderdale Eligible Metropolitan Area.

“We’ve seen clients who, as their life becomes more stable and they have access to more resources, do better at staying in care,” Castrataro observes. “But if you’re too sick to work, then you have no income; and if you have no income, then it threatens the loss of your house. If a client’s house is about to be foreclosed or they are about to file bankruptcy, they’re not thinking about the doctor’s appointment they’re missing.”

Castrataro also notes, “In Broward County, the revenue saved through obtaining public benefits for clients exceeds Legal Aid Service funding from Ryan White by over 5 times. This type of cost savings ensures that Ryan White resources remain targeted to those most in need and that Ryan White remains the payer of last resort.”

Data from the CARE Act Data Report underline

the importance of saving funds for those who need it most. Between 2002 and

2004, the number of visits for case management services and ambulatory/outpatient

medical care among HIV-positive clients increased.13 In 2004, 50 percent

of CARE Act clients were living below the Federal Poverty Level. Only 11

percent had private health insurance, and 31 percent had no health insurance

of any kind (public or private).13

Within the Ryan White program, the principal purpose of outreach is neither HIV counseling and testing nor HIV prevention education. Instead, the purpose is to identify people with unknown HIV disease or those who know their status but are not in care so that they may become aware of—and may be enrolled in—care and treatment services (i.e., case finding). Outreach services may target high-risk communities or individuals. Therefore, outreach programs must be

|

The data indicate growing demand for services funded through the Ryan White Program and reveal the challenging circumstances in which so many PLWHA live. They also convey the importance of active referrals that can make the lives of PLWHA—and their HIV/AIDS medical care—more manageable. The CDC’s Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study found that active referral—”monitor[ing] and track[ing] referrals to assess whether services were received and clients engaged in care—improved the chances of PLWHA being linked to care and staying in that care.”14 By comparison, passive referral did not increase the chances of PLWHA entering care.14,1

As critical as they are, making and tracking appropriate referrals are not always enough to address the overwhelming needs that can burden the people most at risk for not receiving appropriate HIV medical care.

“Very often,” says Standing Rock, “I’m the only individual that is consistently in my clients’ lives. They’ve ‘burned bridges’ with families and friends, whether it is because of substance abuse or crime. It can take 3 days sometimes to get a client into detox because there are so many people trying to get on the lists,” she explains. “I’ll stand in line with them all day. If they don’t get in, then we’ll go back the next day and stand some more.”

Be Persistent

The search never ends for new approaches to remove the barriers

separating PLWHA from appropriate care. In addition to the tools discussed

in this article, many are described in the HRSA-funded New York Academy of

Medicine publication Breaking Barriers: A Toolkit for Getting and Keeping

People in HIV Care.15 For example:

1. Get consent for follow-up.

This step can be complicated by client

fears of being “outed” to family and friends if called at home.

Breaking Barriers suggests “working out a system for finding the client

as early as possible as this is a crucial aspect of keeping the client connected

to medical care.”

2. Create personalized client plans.

Because

client needs and their location along the engagement-in-care continuum change,

plans need to be reviewed on a regular basis.

3. Enroll clients in support groups and skill-building

programs.

Such services can boost clients’ self-esteem and encourage the development

of a support network.

4. Create a hospitable care environment.

Organizations

should avoid long waits in the waiting room between appointments. Scheduling

same-day appointments close together and creating an easygoing atmosphere

are simple, effective approaches.

Many variables determine the effectiveness of engagement and retention interventions. They include client-level issues, such as readiness and health literacy; provider-level features, like cultural competency and staffing; and system-level components. They also include the resources available in the community.

In 2005, HRSA, the CDC, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the National Institutes of Health gathered to discuss epidemiological data about out-of-care PLWHA and what was being done to address the challenges related to this group. One of the meeting’s findings, summarized in the report Outreach: Engaging People in HIV Care was that Ryan White Programs “have had limited success reaching individuals who have never had contact with the care system but do better at retaining clients in care,”16 a finding that underscores that keeping an old relationship intact is often easier than starting a new one.

The group’s recommendation was for Ryan White Programs to “at a minimum, place more focus on retention work [and] develop systems to document missed appointments and client receipt of services.”16 The group went on to suggest that providers undertake activities “that don’t require much funding, such as measuring waiting times; assessing phone coverage and return calls; and conducting an assessment of the physical facility for client comfort, accessibility, etc.”16 Many providers have taken those steps. They must take more still.

Engaging people in care is difficult, and keeping them there is a lifelong pursuit. For providers, the pursuit is fueled by passion—a passion for the work being done as well as for the people being served. And for patients, it’s a pursuit for a better life. To be successful takes mutual respect, persistence, forgiveness and, above all, a lot of hard work.

|

|

| Publisher U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau 5600 Fishers Lane, Suite 7-05 Rockville, MD 20857 Telephone: 301.443.1993 |

| Editor Richard Seaton, Impact Marketing + Communications www.impactmc.net |

| Photography Cover © See Change, www.see-change.net Christopher Hubbard, WWC program manager. Photo by WWC. Staff member, the Community AIDS Resources and Education (CARE) program at Austin Travis Mental Health Mental Retardation Center. Photo by the CARE program. |

| Additional copies are available from the HRSA Information Center, 1.888.ASK.HRSA, and may be downloaded from the Web at www.hab.hrsa.gov. |

ONLINE RESOURCES The following resources are available Making the Connection: Promoting Engagement and Retention in HIV Medical Care Among Hard-to-Reach Populations Outreach: Engaging People in HIV Care Connecting to Care: Workbook I and II Breaking Barriers: A Toolkit for Getting and Keeping People in HIV Care

|

| Director's Notes |

Estimates of the numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) but not in care raise the simple question: Why? We know many of the answers. Often PLWHA do not know their serostatus or even their risk for HIV. Many face countless struggles and are reluctant to take up new ones—like those against barriers to HIV testing and care. Beyond “why” lies the question, “What can be done to help?” We know some of the answers to this question, too. We have to meet people where they are, both in the literal and figurative sense. We must be persistent and culturally competent. We must offer services that reflect the needs of the people we hope to serve. And in everything that we do, we must communicate loudly and clearly to all those on the outside, “We care about you. Come on in.” It sounds easy, but it isn’t. Engagement and retention are roll-up-your-sleeves hard work. When success comes, it is in small numbers, not large ones. But let’s be clear: Reaching out to those on the outside and bringing them into care is one of the most important things that we do. Think about it.

Who needs us more than they do?

|